Attila, the “Scourge of God” was the legendary force that — curiously enough — helped to hold the tottering Roman Empire together for a few more years. Halfway through the fifth century, the Empire was defended by an array of feuding barbarian tribes enlisted as mercenaries. These tribes were united by a common fear of the Huns, who had left Central Asia to invade India, Persia, Central and Eastern Europe and were now threatening the West. Aetius, commander-in-chief of the Roman army, knew the Huns well and their leader, Attila, in particular — the Roman general had once been a hostage in the Huns’ camp. Aetius also knew that the real danger to the Empire came from within, from its disintegrating society. When Attila invaded Gaul, Aetius checked him at a battle fought southeast of Paris, but the Roman “victory” brought only a temporary halt to the inevitable fall of Rome.

On the battlefield of the Campus Mauriacus — to the west of the old Gallo-Roman town of Troyes, some ninety miles southeast of Paris — two armies faced each other in the year 451. In retrospect, they might be seen as the forces of two contrasting worlds: Asia against Europe, the civilization of the plains against that of the towns, pagan barbarism against the Christian heritage of Greece and Rome, but this assessment would be superficial.

Arrayed behind the Hun, Attila, was a horde of tribes more or less under his command: not only his own people but also Ruli, Heruli, Gepidae, Ostrogoths, Lombards and others. Opposed to him in defense of the Roman Empire was the last of the great Romans, the nobleman Aetius. Among his forces, there were hardly any Gallo-Romans, but a mixture of barbarian peoples whose loyalty was not to be relied on: Franks, Burgundians, Alans, Sarmatae, Visigoths; and even a number of Britons who had been recruited indiscriminately, along with the very Germans who had driven them out of their own island territory. What is more, the Visigoths under King Theodoric could well find themselves confronted by their kinsmen, the Ostrogoths, under the command of a Hun. Attila had defeated the Visigoths in a previous battle; he treated the Ostrogoths as run-away slaves. Aetius’ forces had only one common bond: their fear of the Huns who had driven them from the steppes of Russia and the plains of Germany and forced them into Gaul.

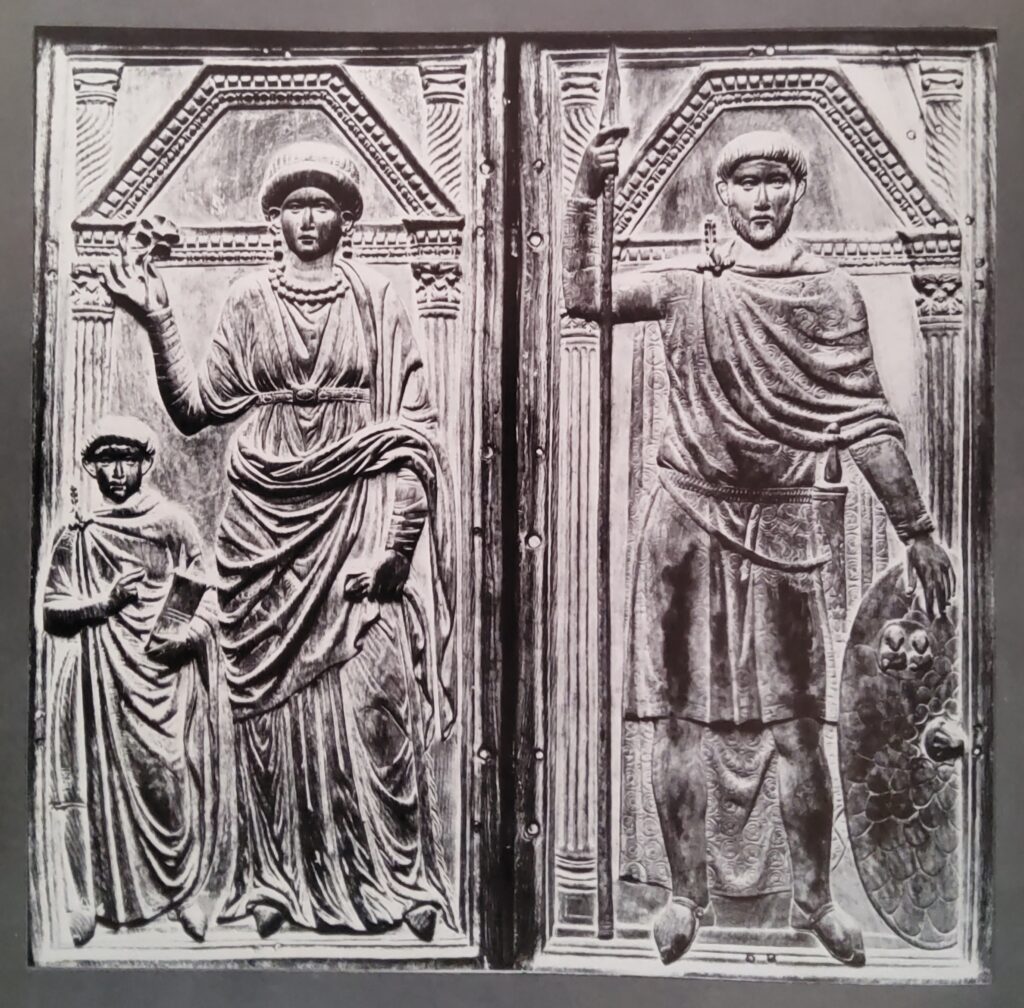

The defense of the Roman Empire at this time, was entrusted to the very people who presented the greatest threat to its peace. Barbarians were enlisted as mercenaries first in small groups, then whole peoples at a time. German soldiers reached the highest ranks. Both the Vandal Stilicho and later the Sueve Ricimer were to command Roman armies.

Unfortunately, these dangerous allies expected regular payment, which the Empire was no longer in a position to supply. Some of them revolted and demanded lands, off which they might live: the Visigoths, who had put themselves at the service of the head of the Eastern Empire in 376, ravaged certain Greek provinces and Italian towns under their chief, Alaric. In 410 they sacked Rome herself before crossing the Alps and finally settling in Aquitaine.

In 407, a particularly violent wave of tribes had broken on Gaul. The Alans, Sueves and Vandals had been driven from Persia by the Huns and had made their way across Europe. The Alans had ended up, as scattered communities on both sides of the Pyrenees; the Sueves were eventually to establish a kingdom in the region of the Douro in the north of what is now Portugal, while the Vandals made their way from Spain to Africa, where they were to dominate the Maghrib for more than a century.

Peoples who had previously been living between the Elbe and the Rhine followed the example of these enterprising invaders and ventured forth in their turn. Burgundians, Alamani and Ripuarian Franks established themselves on the left bank of the Rhine and acquired the status of federate territories. At the same time Angles, Jutes and Saxons were gradually occupying the eastern parts of Britain, from which the kingdom of England was later to emerge.

Attila Has a Hoard of Tribes Under His Command

Behind these German tribes there were the Huns, or rather the various peoples of Hunnish stock, who had left their native steppes of central Asia to invade India and Persia on the one hand, central and eastern Europe on the other.

As soon as he learned that the Huns had crossed the Rhine, Aetius hastily assembled an army from among the barbarian tribes established in Gaul for half a century. This army clearly lacked unity, as Aetius was only too well aware: although there were many reliable troops, the loyalty of the Alans under their king, Sagiban, was not to be relied on.

Attila himself, ruler of the people who occupied the vast plains between the eastern Alps and the Urals, was not Interested in territorial gains but rather, in military victories; above all he was a man drunk with power and greedy for fame. However, he must not be thought of simply as a brute, or a hardened fighting man, who never got down from his horse and who ate his food raw. He was a skilled politician and was gifted with a lively intelligence, to which was allied a certain cruelty. He did not conquer merely in order to possess, but fundamentally to assert his own greatness and extend his dominion.

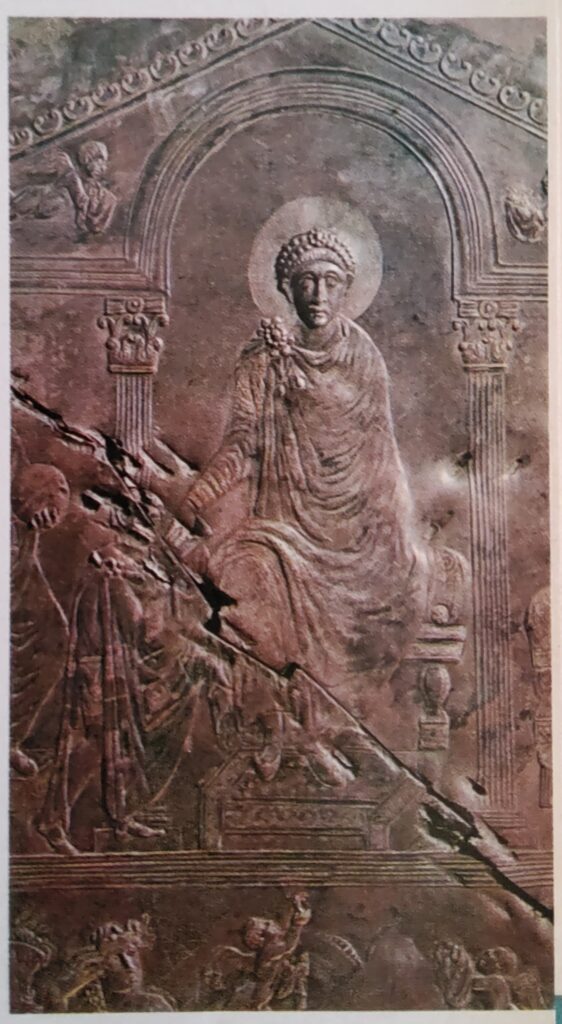

The Roman Empire fascinated this barbarian; in fact, he might well have wished to be a Roman. He exchanged ambassadors and hostages with Constantinople, as a guarantee of the mutual desire for peace. He lived in a palace whose rooms, although of timber, boasted rich carpets and where the pleasures of the Roman bath were enjoyed. He held court in the Roman manner, reclining on a state couch and presided over brilliant banquets at which a wealth of gold plates were seen. His chancellery was managed by Roman scribes and one of his secretaries, the poet Orestes, was to become regent of Italy and father of the last Western Emperor, Romulus Augustulus.

Overweening ambition, was the dominant trait in Attila’s character. Shortly after the death of his uncle, King Rugila, Attila had his own brother Bleda, assassinated, so that he should be sole ruler. This empire was only a brief episode in the history of the Hunnish tribes. In 445 Attila renewed his advance towards the Mediterranean.

Whether war or diplomacy would be required for this advance, the king of the Huns cared little — so long as he was the master. This crafty Oriental knew when to make a strategic withdrawal. On one occasion he had brought pressure on the Eastern Empcror at Constantinople, Theodosius II, to pay him tribute money, but when the feeble Theodosius was succeeded by a more energetic man, Attila turned his attention to Rome.

On this occasion he came in the guise of a friend, but one whose friendship was mixed with impudence. He demanded the hand of the sister of the Emperor Valentinian III, for whose dowry he thought, that half of the Western Empire would be appropriate. Valentinian showed this suitor the door.

What then, was to be the next step for a man who was to become the legendary “Scourge of God”? After his repulse by Constantinople and his humiliation by Rome, he simply went to seek his fortune elsewhere. In the spring of 451, he was on the banks of the Rhine, where he became involved in the internal quarrels of the Ripuarian Franks and announced, that he was going to punish his fugitive slaves, the Visigoths, who were for the time being peacefully installed in Aquitaine.

The man who was governing Gaul at that time, probably knew Attila better than anyone else. Aetius, who was the son of a noble family, had in fact spent part of his youth as a high-ranking hostage at the court of Rugila. Attila had been his companion. He understood, better than anybody else, the nature of the Huns. Surrounded by terrified barbarians who trembled at the Huns’ approach, only Aetius understood Attila’s character. To him fell the task of defending Gaul.

He appreciated the warlike qualities of the Huns. As a nobleman and commander-in-chief of the Roman army, Aetius had enlisted Huns for his personal bodyguards and his hand-picked troops; and it had been with the help of Hunnish auxiliaries, that he had subdued the Burgundians in 435.

Aetius realized that Attila was more concerned with his reputation, than with acquiring territories for which his nomadic horsemen would find no use. He also knew that Attila lacked persistence. Treves, Metz and Reims were burned and Attila’s hordes passed some distance from Paris, where St. Geneviéve urged the people to remain calm and not to flee. In May of 451, Attila besieged Orléans, whose bishop, Aignan, was able to escape in time to seek help. It was at this juncture, that Aetius called up the federal troops based in Gaul and marched on Orléans. Thereupon Attila retreated. Once more, in the face of firm resolution on the part of his enemies, he decided to abandon his original plans and explore fresh fields.

Attila is halted at the Campus Mauriacus

At the Campus Mauriacus, however, Aetius caught up with Attila at long last. The carnage and ferocity of this battle were to become legendary. Theodoric, the king of the Visigoths, was killed in the fight, but the battle was indecisive: neither the troops of Attila, nor those of Aetius were overwhelmed. Attila, however, had been halted in his tracks and this was sufficient: he had not wished to fight and so once again, he turned back and re-crossed the Rhine without hindrance. Aetius could easily have pursued the retreating Huns and harassed them, but infact, he did nothing. He made no effort to exploit his victory and he even sent home the barbarian contingents that made up his army.

A great deal of criticism has been directed at this strange decision, which left at the gates of the Roman Empire a potential invader who might at any time, renew his attacks. Was it for want of resolution? Aetius was not lacking in decisiveness, as his brilliant campaigns in Africa bear witness. It has sometimes been thought that the earlier friendship of the two opponents and their youthful comradeship, may have influenced his decision, but it is scarcely likely that Aetius would have Iet such a sentiment, come before the interests of the Empire.

Nor must one forget, that Aetius had a profound knowledge of Attila’s character: he was ambitious and arrogant, but in the last resort he was less of a menace than his people had been three centuries earlier, when they had established themselves north of the Black Sea and dominated all who had not fled. Aetius alone, realized that the fear of the Huns was out of proportion, to the real danger they posed.

He also knew, that the greater danger that threatened the West, was an internal one; the break-up caused by the rivalry of peoples, who had only recently established themselves and the collapse of Roman hegemony. For many years, he had fought all over Gaul against the banditry of the Bagaudac and had kept guard on frontiers that he had no choice, but to entrust to the federate peoples. It was only the fear of the Hun, that gave these groups a certain degree of cohesion.

The defeat of Attila, could only lead to the outbreak of quarrels and revolts among the very people who were defending the Empire. It would therefore be better to leave a man like Attila on the other side of the Rhine, so as to keep the federate peoples in a state of vigilance. This would ensure internal peace and security from external attack. Fear of the Hun was to serve Aetius’ purpose in his relations with the Burgundians, Visigoths and Franks.

As always, when checked in one direction, Attila decided to try his luck elsewhere. In 452 he invaded Italy; Aquileia, Pavia and Milan fell into his hands. The Emperor Valentinian III, was jealous of Aetius’ prestige and instead of calling upon him for help, fell back on Rome, where he proceeded to negotiate with the Hun. Pope Leo I intervened and a payment of tribute was agreed upon. Attila had humiliated the Western Empire and he retired satisfied.

The death of the king of the Huns in 453, was also the death knell of the dominion that had been founded on his extraordinary character. The subject peoples revolted and the Huns themselves, split up. It was the end of the Hunnish threat and also, the end of the Western Empire.

Inspite of Aetius’ efforts, the unity of the western world was shattered. The Roman Empire had surrived many other revolts, but the object of almost all of these was to usurp power at Rome and acquire the universal domination, that went with the title of Emperor. From this time onwards, national wars were to be the common lot of Europe.

There was no central authority that could withstand the forces of disintegration. Valentinian killed Aetius, who he realized would eventually supplant him, only to be assassinated in his turn. In Gaul the Visigoths and the Burgundians gained their independence and their kings promulgated laws which were binding on the Romans who were now under their authority. They had already forgotten that they themselves were intruders. On the northern frontier, the Franks began their slow progress towards Belgium. Soon, the last Emperor in the West, Romulus Augustulus, was to be dethroned by the king of the Heruli, Odoacer. The Ostrogoths, who had formerly been subject to the Huns, made an incursion into Italy at the instigation of the Eastern Emperor, but were eventually to found an independent kingdom.

The Heritage of Rome Survives

As soon as Attila disappeared from the scene, a whole new world appeared. The Visigoths, the Burgundians and other federate peoples, who had been called to defend Rome, had in fact been defending their new lands and their future kingdoms. From this time onward, the West was no longer Roman; it was barbarian and the barbarians were well aware of it.

They did not, however, make a clean sweep of the civilization that they had found in the Roman Empire. In varying degrees they had all felt the same fascination as Attila. The Ostrogoth Theodoric modeled his administration on the same lines and with the same framework as that of Rome and staffed it with Romans. He proceeded also, to surround himself with men of letters, of whom the most famous was Cassiodorus. The Visigoth Ataulf, had donned the woolen toga of the Romans when he married the Roman princess, Galla Placidia, to the sound of a wedding hymn. When his successors were driven from Gaul by Clovis, they established at Toledo a brilliant court. One of Ataulf’s successors became a composer of hymns.

Throughout the entire West it was Christianity, the religion of the Romans, that gradually prevailed over that of the invaders, which was either German paganism or Arian Christianity. Mixed marriages, which increased enormously in the course of time, were to eliminate many of the differences between Roman and barbarian families.

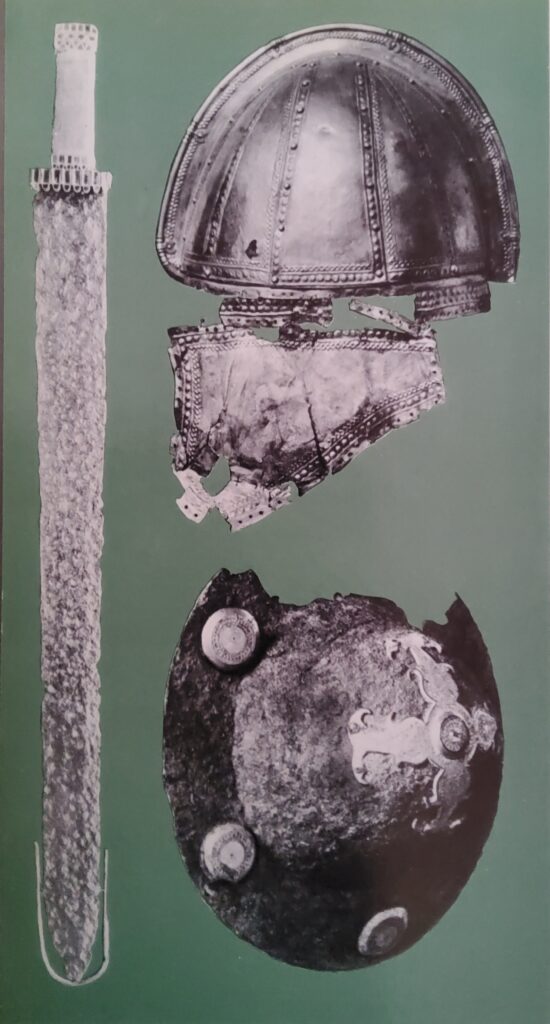

The Germanic peoples had added their social and cultural heritage to that of ancient Rome and it would be unjust to ignore it. They contributed a different conception of society and the family, based on the hereditary principle, the contractual obligations of the craft unions and the vested security of public authority. It was due to the influence of German ideas, that over part of Europe the conceptions of royal power, class structure and the disposition of property, slowly evolved over a thousand years. Although they did not despise the written word as a means of administration, the barbarians made the verbal communication, as evidence or declaration of intention, the fundamental basis of the western juridical system. Being warriors and nomads, they accepted the idea that service in the army carried greater prestige than work in the fields. The medieval lord was to imitate the German warrior and not Cincinnatus.

They introduced new technical processes into Europe, notably in metalworking, both for armour and for jewellry. They also widened the range of artistic conception with their own sources of inspiration and choice of themes.

At the end of the fifth century, Clovis extended the kingdom of the Salian Franks in the northern half of Gaul, at the expense of the remaining Roman territory and the other Frankish tribes. In 507, Clovis also subdued the Visigothic kingdom of Aquitaine and some years later, his sons annexed the kingdom of Burgundy. However, the Franks were already divided among themselves and engaged in internecine strife. Neustria, Austrasia, Burgundy and Aquitaine, were continually engaged in hostilities until the accession of the Pepin dynasty, at the end of the seventh century. Either in concert or separately, the Franks joined issue against the peoples of Germany, in particular the Thuringians and Bavarians.

During the same period, the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms all aspired to dominate Britain. The fortunes of war gave pride of place, first to Kent and then to Northumbria and Mercia.

Within the boundaries of barbarian Europe itself, hostilities were engaged in with equal ardour. Britons and Anglo-Saxons were so antagonistic, that missionaries had to be sent from Rome to evangelize England. In Italy, the partial failure of Justinian’s attempt at reconquest, left unprotected both the citizens of Byzantium and the last arrivals from the German migration, the Lombards, who had established themselves in the north and centre of Italy, in the middle of the sixth century.

Europe then remained divided. The unity that Charlemagne succeeded in achieving, was to last only the length of his reign and the coronation of Christmas A.D. 800, marks a summit rather than a beginning. The Church itself reflected the political fragmentation. The authority of the Pope seldom prevailed and the religious synods, brought together only the bishops of a single province or kingdom. The Latin language survived and was generally adopted, but each group modified it, in its own way. In fact, there was only one unifying factor to act as a link between the Empire of Constantine and that of Charlemagne: the Christian faith.