Charlemagne crowned, at a solemn moment during the celebration of Mass in Rome’s St. Peter’s Basilica on Christmas Day of the year 800. Pope Leo III stopped and turned toward the large man kneeling in front of the altar. Then, in a dramatic gesture that has been the topic of countless historical arguments since, Leo crowned Charles, King of the Franks, as the new Emperor of the Romans. The coronation apparently took even Charles by surprise; and it probably displeased him as well, since it seemed to imply that he received his power from the Pope. Indeed, this may have been Leo’s aim, for only a year before he had been driven out of the city by a rebellious population and he was now eager to reassert his authority. Whatever Leo’s motives, his action was of momentous significance, in creating a European Christian empire. In continuing the division between East-West and in sowing seeds of conflict between Church and State.

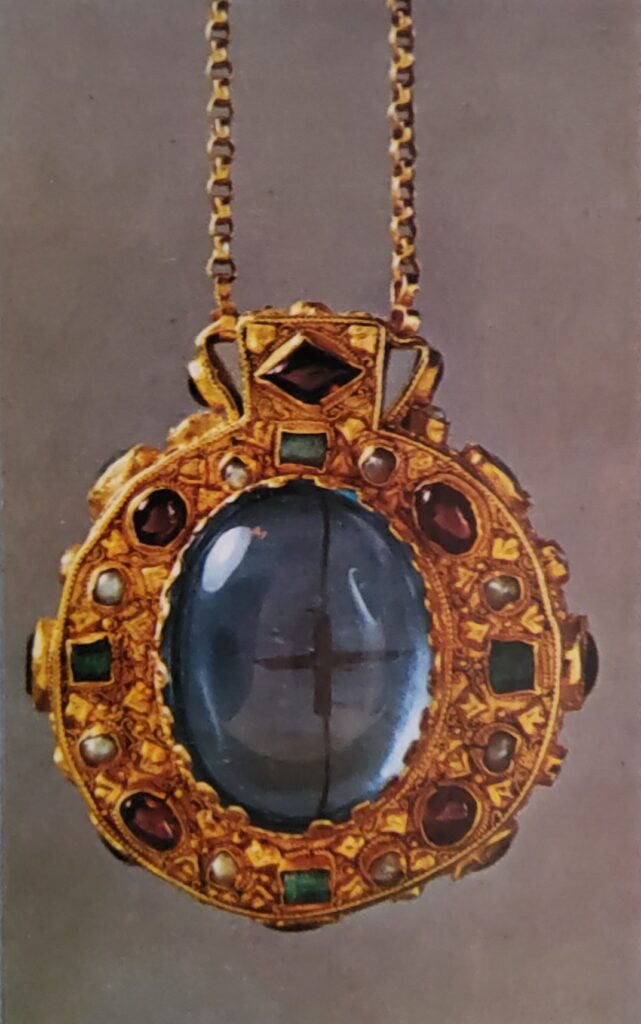

On Christmas Day in the year 800, Charlemagne heard Mass in St. Peter’s in Rome. As he knelt at prayer, Pope Leo III placed on his head a gold circlet in token of an imperial crown and the Romans proclaimed him Emperor: “To Charles Augustus, crowned by God, the great and peace-giving Emperor of the Romans, life and victory!”

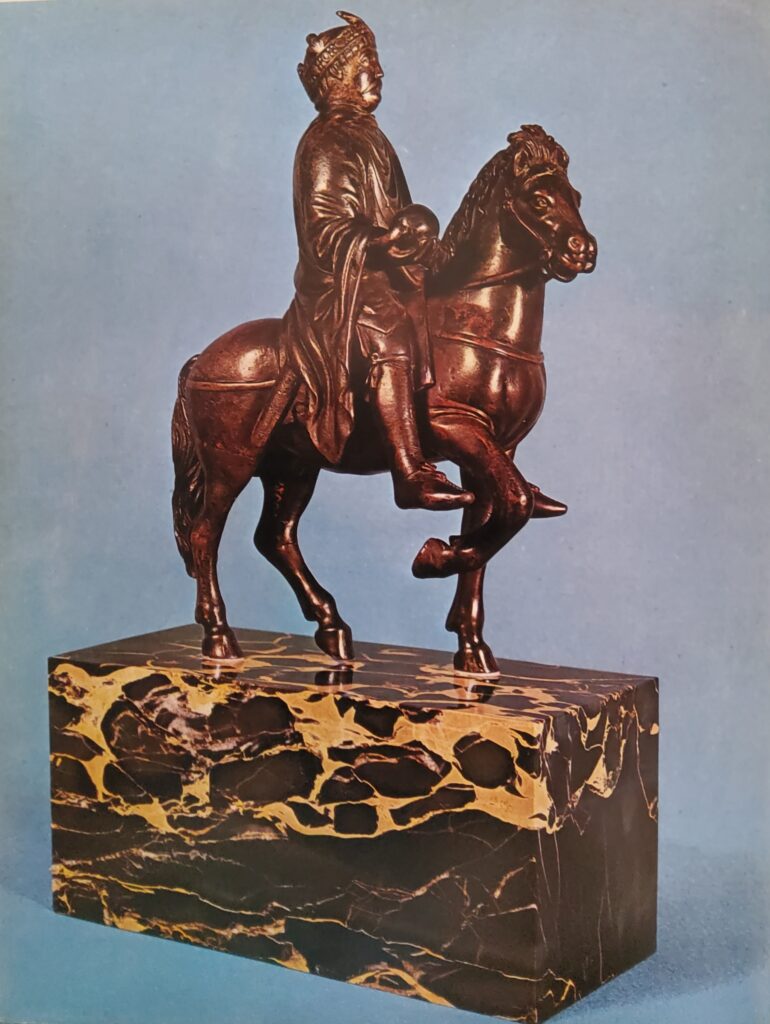

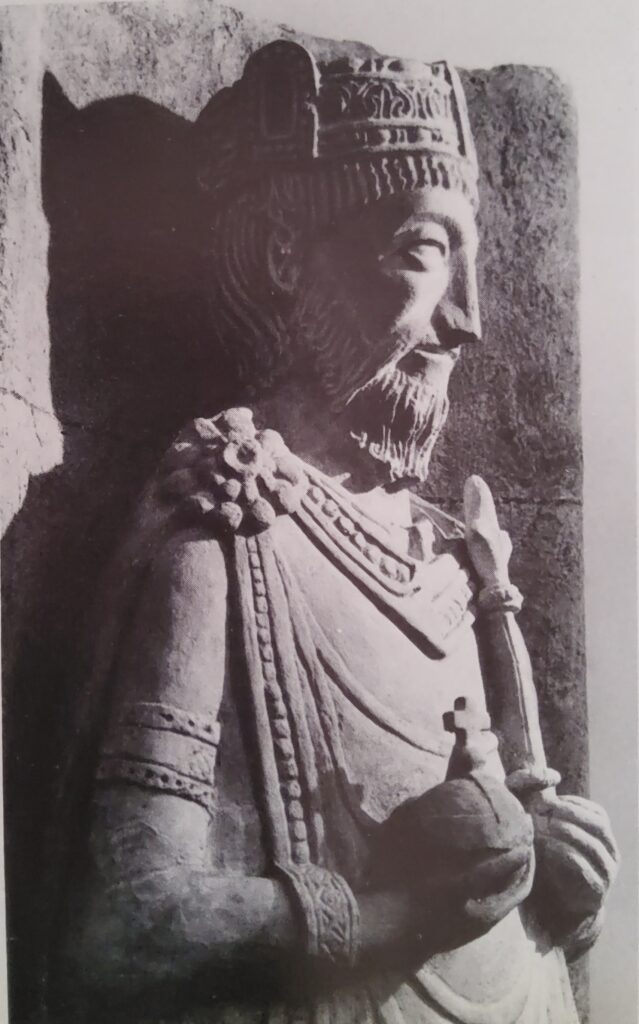

Charlemagne the Frank was a huge man, six feet and four inches tall, broadly built. He spoke quietly and was a cheerful, talkative man, who enjoyed the debating matches that were popular among the Germanic races. He drank sparsely but ate a great deal and detested wearing fine clothes made of silk. He favoured the shirt and linen tunic of the Franks over tight hose and in winter a cloak made from the skins of otters or rats. He wore a blue serge cloak and carried a short sword with a hilt of silver or gold. Charlemagne loved hunting, riding and swimming; he loved women, too. Apart from those he was wedded to by Christian marriage, he had some wives under Germanic folk laws and four concubines. Charlemagne valued culture and the learning of the clerics — he himself understood Latin, but probably could not write it, since it was only with difficulty that he could form the letters of his name for a signature.

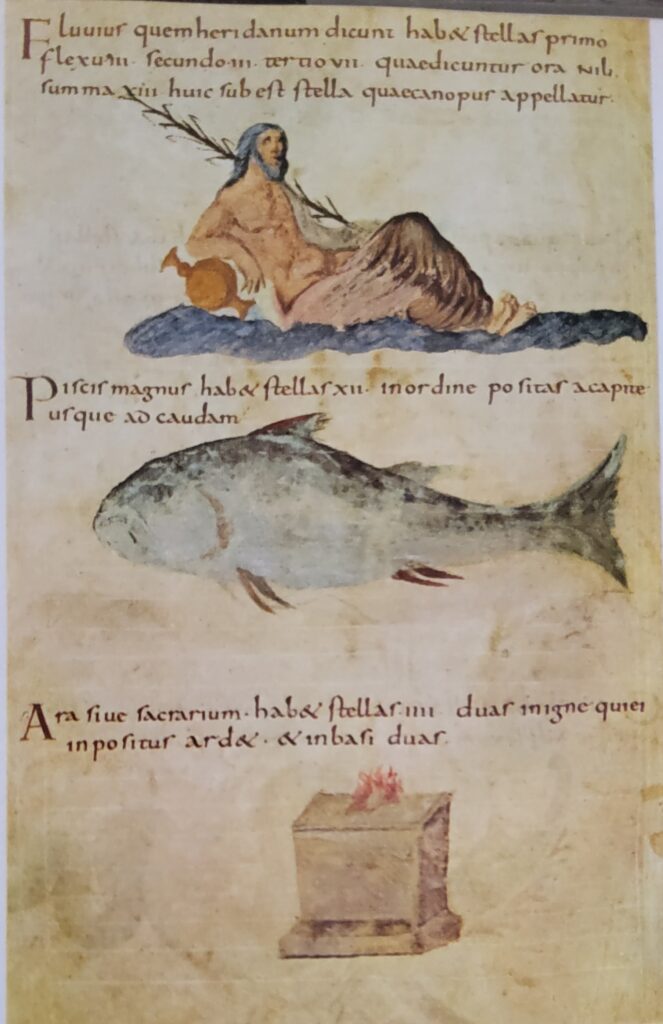

Charlemagne wanted to see ancient Rome reborn in his capital city. In Aix, near the famous hot springs, the imperial chapel was built as an octagon, probably modelled on the Church of the Holy Sepulcher at Jerusalem. Apart from the cathedral and the sacrum palatium where the Frankish king intended to live, there was a third building, named the “Lateran”. Aix, like Constantinople, was to be a second Rome.

Pope Leo III was made aware of this great project of Charlemagne’s when he fled from Rome to the town of Paderborn in Germany in the summer of 799. The people of Rome had driven him out and he sought help from “the protector of the Romans,” Charlemagne. Rome (Romanitas) and Christendom (christianitas) were identical to Charlemagne and for him, both concepts were religious. However, “Rome” and “Christendom” had totally different meanings for the Pope and for the Emperor in Constantinople. The latter considered himself to be the only legitimate Roman Emperor and his Greek Orthodox Church the only true one. The Pope, for his part, saw himself as the successor of St. Peter and therefore, the one true Roman. His concept of Rome was implicitly – in his attempt to renew papal Rome – the axis of the Christian world.

Charlemagne’s plan to turn Aix into a second Rome could only alarm the Pope and probably, was the basic reason for the coronation of 800 A. D. The idea of transferring the papacy from Rome to Aix must already have taken shape by 799. Once in Aix, the Pope would have been only primus inter pares, the first of the imperial bishops, in the world’s eyes.

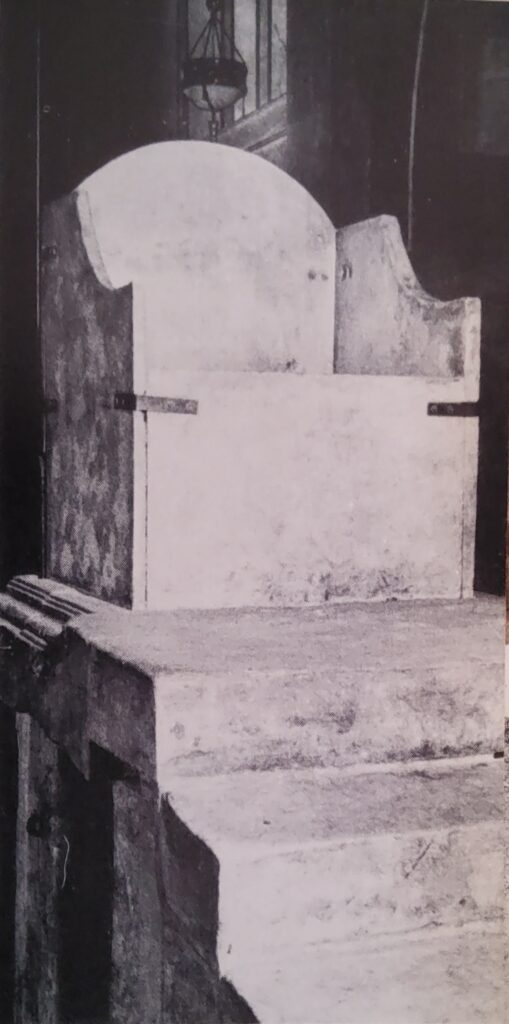

At the imperial coronation on Christmas Day, A.D. 800, at least four opposing claims came into conflict: the claims of the Franks, the papacy, the people of Rome and Byzantium. Historians always have and probably always will argue, about the correct interpretation of this event, which was both political and religious; and embodied both a sacred and a political constitution for Latin Europe and the West. The argument arises from the conflicts that existed at the time. Charlemagne remained the short-term victor. For him, as for his Franks, his subjects in Lombardy and the Anglo-Saxons, Irish and Spaniards who were his ideological allies, the imperial coronation of 800 A. D., was a coronation at the hands of God Himself. Charlemagne the king and priest, was the successor to the priest-kings of the Old Testament, “after the order of Melchisedech.” Charlemagne, the “new David,” was enthroned in Aix on a sacred imitation of King Solomon’s throne. He also saw himself as the successor of Justinian, carrying out and adding to the latter’s enactments.

For the Germanic peoples who had been subjugated or won back by Charlemagne’s “strong arm,” his coronation was the divinely ordained confirmation of the great conqueror’s role, since God had first made him “Emperor”, on the battlefield.

It is certain that Charlemagne and his advisers did not consider the imperial coronation of 800 A.D., as a papal claim to spiritual and ecclesiastical authority, over the rank and office of the Emperor. Charlemagne, in any case, wanted to avoid an act of provocation against the Emperor in Byzantium.

The Pope, who was the “second victor” of 800 A.D., had quite different intentions. Leo III, a problematical figure whose personality remains obscure, formed part of a great tradition which was to receive new impetus, later in the ninth century and which led through Gregory VII to the powerful figures of the twelfth century, Innocent III and Innocent IV.

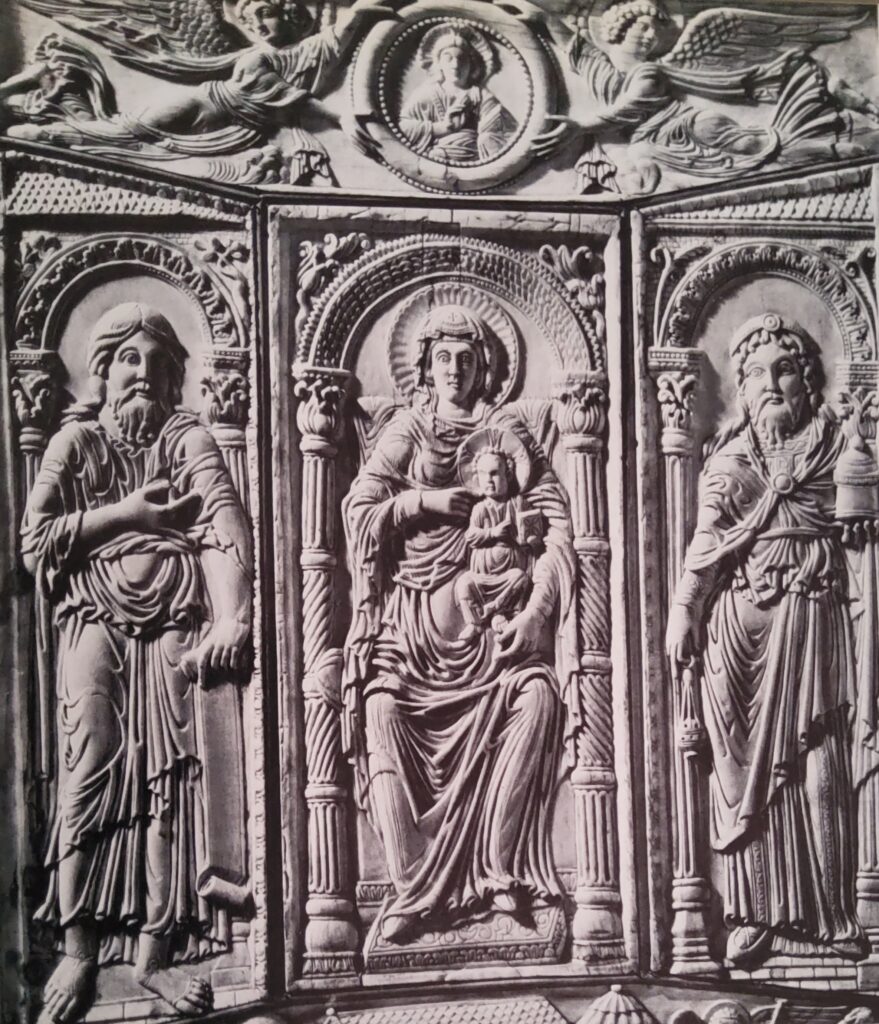

The popes and their assistants wove the strong web of ideology that later entangled and overthrew the power of the Western Emperors: from Constantine’s day, the Pope was the real ruler of Rome; he always handed the imperial office on to his candidates, once the majesty of the Emperor had been transferred from Constantinople to Rome.

Leo’s coronation of Charlemagne, which surprised and embittered the latter like an act of aggression, was aimed against the Emperor in Constantinople, against the Frankish king and against the people of Rome themselves, who were pressed into service for the ceremony by the Pope; they had to chant the ancient Roman acclamation, the ceremonial words of the old imperial liturgy — immediately after the coronation, in order to make it legal and binding. The Roman citizens who collaborated with Leo in this act, believed that it gave them the right to accept or reject the Pope’s choice of Emperor — who might be a powerful ally in the still unresolved conflict of the Romans themselves with their popes. Pope Leo, however, intended their role to be merely one of helpers; the Franks, to their chagrin, were allotted the role of mere onlookers. They were allowed to do or say nothing at the ceremony.

Leo III, would have liked to add a second ceremony to this coronation, the first time a Pope had ever crowned an Emperor. He had planned Charlemagne’s betrothal to the Empress Irene at Constantinople —but she was deposed before the betrothal could be arranged. If he had succeeded in this, Leo would have achieved that world primacy as head of both Latin and Greek Christendom, which the popes, as leaders of Europe, were to strive for at the time of the Crusades. Hadrian I, Leo’s predecessor, had already declared that the Roman Church was caput totius mundi — the head of the whole world. Why did Charlemagne accede to the Pope’s plans? Why did he go to Rome at all? Why expose himself to the obvious risk that the Pope would take over the coronation and exploit it for his own ends? One must remember here that Charlemagne’s chief aim was to be crowned as Emperor; but he intended the coronation to take place on his own territory, after careful preparations by his political and religious advisers. On December 23 of 800 A.D., two days before the coronation, the Patriarch of Jerusalem’s legates handed over to Charlemagne a key and a banner, to symbolize that they were handing over to him as master and protector of Christendom the sacred places in the Holy Land.

The Protector of Christendom

Charlemagne, as protector of Christendom, believed that the true Christendom was the ecclesiastical Latin Christendom of Rome led by the papacy. The Frankish church was firmly oriented toward Rome. The age-old Roman faith of the Franks was based on the sanctity of St. Peter and was centered on the papacy. Charlemagne was the father of the Latin West, of the traditions that have formed the basis of Western European culture and its schools and universities, right up to the present day.

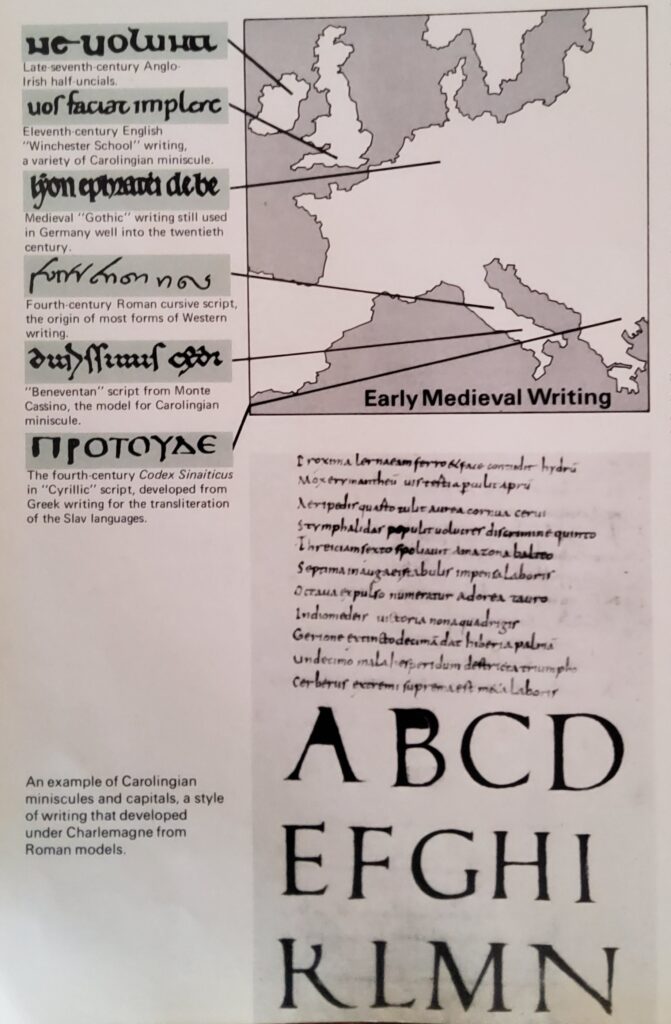

The Carolingian miniscule, is the ancestor of modern European printing. It is true that in Charlemagne’s Empire, Latin and to a certain extent also Greek education, were better and more productively represented by the English schoolmen than by the decadent, needy scholars of Rome. By Charlemagne’s day, Rome had become a cultural and moral desert. It could not be compared in any way with southern Italy, where a rich culture based on ancient Greece still flourished, nor with the civilization of the Lombard kingdom in northern Italy.

The culture acquired by England from the time of Theodore of Tarsus and Bishop Benedict, was available to the men of Charlemagne’s Empire. The scholars from the Continent had free access to England’s schools and libraries. Throughout the whole of the eighth century, England had sent the finest and most educated of her sons across the Channel as teachers and missionaries. From the time of St. Boniface to the time of Alcuin, the Church of the Frankish Empire depended very much on the wisdom and scholarship of British monks.

These men, also acknowledged Rome as their master. For Charlemagne, the labourious work of political and cultural unification of the vaned peoples, races and territories of his great Empire, could only be based on Roman (and this meant Latin and Christian) belief and culture. His title of imperator Romanum gubernans imperium, which he preferred to the less ambiguous imperator Romanorum, chiefly signified to him, that he was Emperor of all Latin Christendom; the only divinely inspired Christendom, since the Greeks with their contentious discussions, were always in danger of heresy.

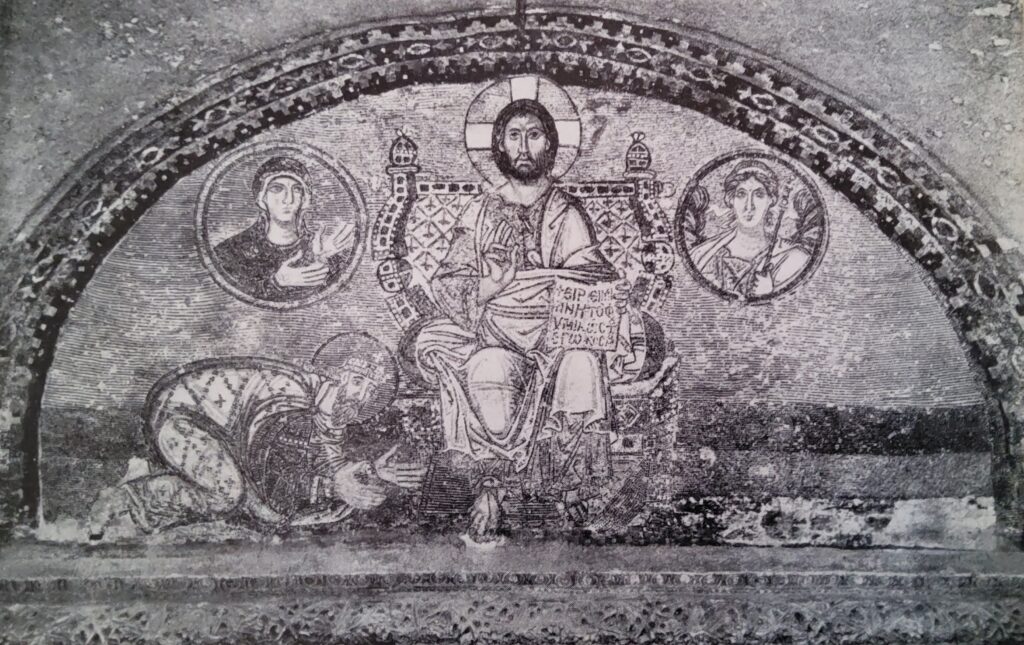

It was in this context, that Charlemagne needed the power of the Roman papacy against the Greeks. His aim was the coexistence of the two empires and he strived for equality in rank and power with the Eastern Emperor, whose title he recognized as legitimate. He imitated his rival by calling his court “sacral” (sacer), following the custom of the Byzantines; Greek elements were absorbed into the Carolingian civilization. The most obvious example of the imitation of Byzantium occurred in the adoration of Charlemagne by the Pope after the coronation. Leo III, stood to crown Charlemagne, when the latter rose after his prayers and then threw himself down before Charlemagne, in the Byzantine custom of homage and sacral recognition of the crowned Emperor. This seemed monstrous to subsequent popes and was never repeated, for in their conception St. Peter, that is, the Pope, “created” the Empror.

The coronation of 800 A. D. must be considered from every point of view, a decisive step in the development of the great conflict between East and West which has overshadowed Europe from late antiquity up to modern day. It is a conflict between Greeks and Latins, between the Greek and Latin churches, Constantinople and Rome.

The Synod of Frankfurt

The synod of Frankfurt in A.D. 794 was the immediate prologue to the events of A. D. 800. It was an attempt to prove that the Greek Church had departed from the true Christian faith and gone over to the side of evil and the antichrist in its heretical worship of images. The “orthodox council” of Frankfurt represented an attempt to discredit the second synod of Nicaea (A. D. 787). It exploited the material that had been prepared in the Libri Carolini by a court theologian, probably Theodulf of Orléans. The Franks accused the Byzantine Church of setting up idols; the conflict over the right degree of worship to be accorded to the holy images infact continued for centuries in Byzantium.

However, the Frankfurt synod’s real object of attack was the Eastern Roman emperors — the Byzantine rulers were accused of elevating themselves to the level of false gods in their claim to rule in conjunction with God and to be themselves divine. It was said that in the evil city of Constantinople people even spoke of the “holy ears” of the ruler. The synod of Frankfurt maintained that far from being equal to the apostles (Constantine the Great was the first to describe himself as “equal to the apostles” and even “the thirteenth apostle”), these emperors were all-too-ordinary mortals, in their pursuit of earthly transient aims.

This attack on the part of the theologians coincided with the objectives of the Roman popes, who were attempting throughout the ninth century to undermine the sacral position of the Eastern emperors. The papacy assumed all the sacral title and claims of the Eastern emperors and indeed went far beyond them; by the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the ideologists of the curia were referring to the Pope as papa-deus, or “Pope-God.”

This rivalry shown by the Carolingian theologians and men of politics with Constantinople, was a symptom of the feelings of inferiority the Roman and Latin clerics and theologians experienced, when confronted with the far finer civilization of the East. They were greatly inferior to the scholars of the Eastern Church intellectually, spiritually and ecclesiastically; in the fourth century, not a single theologian in the West could follow the subtle intellectual disputations in the Greek church on the question of the Trinity. If, by the end of the eighth century, the West had caught up to a certain extent, chiefly through the work of the theologians of the British Isles and Spain, there was still no question of any equality between the Franks and the Byzantines in the field of culture and learning. Charlemagne’s court theologians were all too aware of this and knew that they would be considered barbarians in Constantinople.

The Frankfurt synod’s goal was nothing less than a demonstration, that now, the Latin Church alone represented the true orthodoxy. The Greeks were denounced as false, heretical, unreliable, evil, gossiping and treacherous; right into the nineteenth century and beyond, such advocates of the Pope’s infallibility as de Maistre have repeated this cliché.

If the “one true word of God” had gone over from the East to the West, surely the imperial crown should go as well. An unexpected event now came to the aid of the Carolingian politicians: in 797 the Emperor of Constantinople was deposed and replaced by a woman. According to the masculine theology of the West, which denied equal birth rights to women from St. Augustine’s day right up to the twentieth century, Irene was not entitled to rule. Once more Frankish goals coincided with the plans of the papacy. As the Libri Carolini expressed it, “the fragility of the [feminine] sex and the fickleness of the [feminine] heart do not permit [a woman] to assume the highest positions in matters of faith or rank, but force her to submit to masculine authority.” However, both “masculine authorities,” Pope Leo III and the Emperor Charlemagne, knew that the reality of Byzantine rule could not be overcome with purely theological arguments. Once Charlemagne became Emperor he dropped the issue of image-worship. As Emperor, he set out to establish friendly relations with the Byzantine court. We can safely assume today that an ambassador of Charlemagne’s, accompanied by papal envoys, actually traveled to Constantinople to woo the Empress Irene, no longer in her first youth, as a bride for Charlemagne.

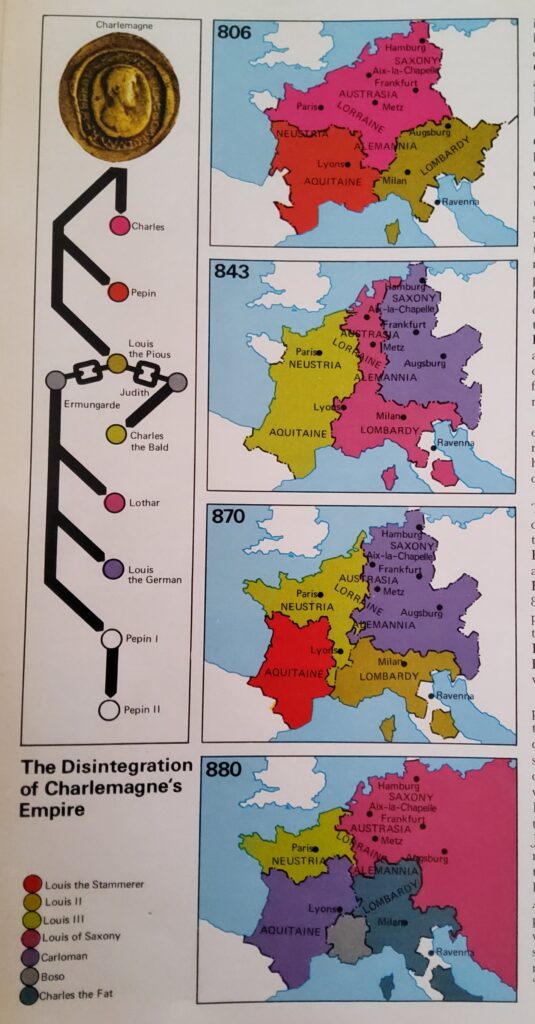

Collapse of the Empire

The Empress Irene was not unwilling to be Charlemagne’s bride, but the powerful patricians of her Empire rebelled. Irene was banished to a remote convent and died a few months after this coup d’état, which took place before the eyes of the envoys from the West. Once again a man was Emperor in Constantinople: Nicephorus, formerly the Logothete, or minister of finance. However, the Frankish envoys returned with a Byzantine delegation which was to negotiate the recognition of Charlemagne as Emperor. Two years before his death, a settlement was finally reached: a new Byzantine delegation officially acclaimed Charlemagne as “Emperor” — though not as Roman Emperor. The Emperor of the Romans and he alone, was to remain the Greek ruler. According to Byzantine imperial law, there could be any number of nominal emperors; later on, for example, an Emperor of the Bulgarians was recognized.

Charlemagne for his part, gave up his claims to extend his dominion over the East. This was more easily done, as he was to be fully occupied until his death in trying to keep the peace among the different races and tribes of his enormous Empire. The collapse of that Empire began after his death. The papacy at once made a bid to take over the dominant role, as the imperial coronation of Louis the Pious in Rome (A. D. 816) demonstrated. The Pope managed on this occasion to combine the anointing with the coronation for the first time. The Romans, who had been the Pope’s adjuncts in A. D. 800, were now completely excluded and their approval disdained. The new, epoch-making liturgy of this imperial coronation made it clear that St. Peter created the Roman Emperor. Rome, the Rome of the papacy, became the focal point of the whole Christian world.

One final point needs to be made about the imperial coronation on Christmas Day, A.D. 800. In the thousand years that were to follow before the downfall of the old Europe, which received its first severe blow in the French Revolution and finally came to an end in World War 1, this coronation was remembered by kings, emperors and princes of East and West, North and South alike. Right into the East, into Russia and beyond, as far as Jerusalem and Baghdad, Charlemagne became the mystical definition of the great ruler, the Caesar and the Augustus, of the Christian world. Napoleon believed himself to be Charlemagne’s reincarnation. After World War 2, Western politicians spoke of the political and economic coalition of “Carolingian” western Europe which was to withstand the pressures from the East; and Soviet Russian diplomacy reproduced the subtle and devious methods of its “Byzantine ancestor”.