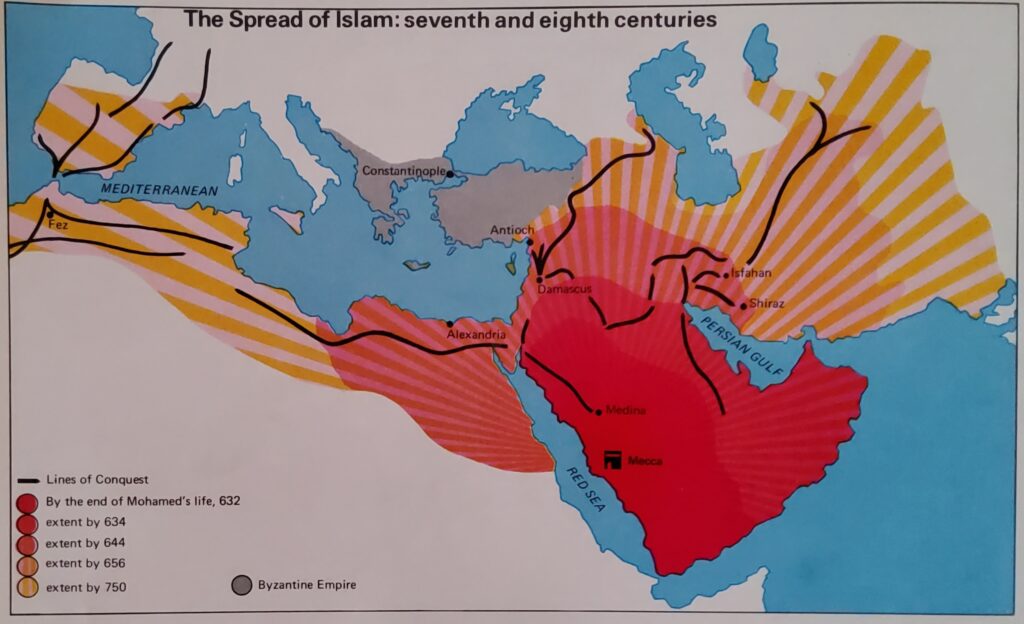

The flight to Medina, was made by the prophet Mohammed, when he fled from his native Mecca, in hopes of finding a more receptive audience for his message. This event of 622, the Hegira, marks the beginning of the new Moslem religion and the beginning of a dynamic new civilization in the Middle East. Mohammed himself, proved to be both an inspired religious leader and an astute politician, creating a theocracy and presiding over it, as Allah’s Messenger. He also was a military leader. Mecca was soon brought into the Moslem orbit and at Mohammed’s death in 632 the entire Arabian Peninsula was his, but it remained for his successors, the caliphs, to impose Islamic rule over much of Asia and Africa and to bring a frightening challenge to Christian Europe.

The Moslem era begins in 622 A.D. the date of the Hegira, Mohammed’s emigration from his home town of Mecca to the neighbouring city of Medina. In fixing the date for the initiation of the Moslem era, Caliph Omar, successor to Mohammed’s first Caliph, Abu Bakr, is said to have hesitated between choosing the Hegira, the date of Mohammed’s birth, or the date he first accepted the vocation of prophet. When Omar chose the first alternative, he no doubt had good practical reasons: the date of the Hegira was better fixed in men’s minds than the less spectacular moment when Mohammed was finally convinced of his divine mission.

Yet the Caliph may also have been quite conscious of the fact that it was the Hegira, even more than the first appearance of the angel Gabriel to Mohammed, that marked the historical epoch of the rise of Islam. In Mecca, Mohammed — a tradesman and previously a caravan leader — had gathered around him a considerable number of followers. Yet, faced with the resistance of the leading families, he was unable to attain political power — despite the fact that the visionary side of his character, went hand-in-hand with a genius for affairs and a mastery over men. Having become familiar with Judaism and Christianity, he felt it was his prophetic mission to warn his pagan compatriots of the coming day of judgment and urge them to turn to the one true God — and the ethical duties imposed by him upon man — before it was too late. To the astute politicians of Mecca, Mohammed might have appeared as an impractical dreamer or, as they less politely put it, a madman.

Latent in Mohammed were immense political gifts, which found only limited scope in the role of venerated head, of a small and persecuted religious community; of these immense gifts his later career as the founder of a powerful religious state in Medina, bears eloquent witness. Having failed to satisfy his political aspirations in Mecca, Mohammed cast about for more promising fields of action in the neighbouring town of Taif and among different Bedouin tribes, but without avail. His opportunity came, from the great oasis of Yathrib, north of Mecca, the centre of which, was also called Medina, i.e. “the city.” The oasis was inhabited by several tribes that followed the Jewish religion and by two others, the Aws and the Khazraj, that were pagans and warred among themselves.

Some Medinians came in contact with Mohammed and in 621. During the pilgrimage to the pagan sanctuarics near Mecca, a number of them met Mohammed on a mountain pass outside Mecca and accepted his main religious teachings. In the course of the next year, more Medinians adhered to the teaching of the prophet and at the next pilgrimage, the Medinian contingent included a considerable number of Mohammed’s followers. At “the second treaty of the pass” they agreed that Mohammed would come to Medina and that they would give him full protection.

After this agreement was reached, Mohammed’s Meccan followers began to slip away from the city and find their way to Medina, in anticipation of the eventual emigration of their Prophet. Their empty houses, with their doors thrown open by the wind, made (so the traditional account says) a sad impression upon the Meccans who passed by and expressed their grief at the disruption caused by Mohammed in the life of the city. At last, of the Moslem community only Mohammed himself, his cousin Ali, Abu Bakr (who was one of the Prophet’s oldest adherents and was particularly close to him) and their womenfolk, remained.

By September, 622, Mohammed himself was ready to escape from his native city. The Meccans obviously did not relish the idea of the persecuted community of Moslems finding a new home in Medina and possibly causing trouble to them. Therefore they were determined to prevent Mohammed leaving and joining his followers in Medina; he was forced to flee. Although the word Hegira (or, to render the Arabic more exactly, Hira) does not mean “flight,” as it is often translated, but rather, “emigration”.

Reward of a Hundred Camels

One September day, Mohammed informed Abu Bakr that he was to accompany him. His cousin Ali, would be left behind to look after the womenfolk. Abu Bakr took with him all the money he had, amounting to five or six thousand dirhams. (Dirham was the name of the silver coins currency in Mecca, no doubt mainly Persian pieces, with the image of the Persian king; the Meccans minted no coins of their own. A dirham would be about four grams of silver.) He also arranged with one of his sons, to come every day to their hiding place, in order to bring news from the city and ordered a freedman of his, Amir the son of Fuhayra, to graze some sheep in the desert in order to provide fresh milk and meat every night.

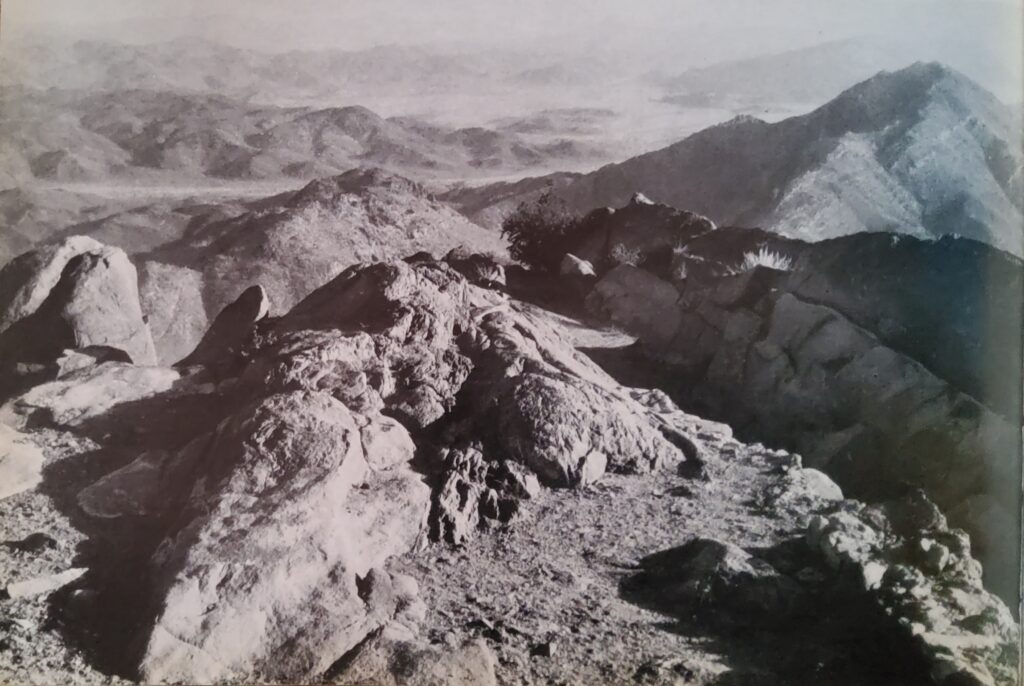

The two fugitives left Abu Bakr’s house by a back door and hid in a cave of Mount Thawr, an hour’s journey to the south of Mecca. This was in the opposite direction to that of Medina and thus, they hoped to evade search parties who would look for them on the road leading north. Mohammed and Abu Bakr remained in the cave for three days, living off the milk and meat of the sheep brought nightly by Amir and other food brought from Mecca by a daughter of Abu Bakr. In later times, many legends were woven around the stay in the cave, in marked contrast to the sober realism of the earlier accounts, the essential truth of which is confirmed by Mohammed’s own reference to the cave in a passage of the Koran (9:40): “If you do not help him, yet God had helped him already when the unbelievers drove him forth the second of two, when the two were in the cave, when he said to his companion, “Sorrow not; surely God is with us”.

The rulers of Mecca promised a reward of a hundred camels for the return of the fugitives. After three days, when the hue and cry had died down, the two men set out on their journey. The practical Abu Bakr had arranged every detail. He had previously given two camels to a Bedouin called Abdullah, son of Arqat, who was to serve them as guide. The Bedouin now appeared riding his own camel and bringing the two camels for Mohammed and Abu Bakr. Abu Bakr’s daughter also arrived with provisions for the journey. The freedman Amir rode behind Abu Bakr on the same camel and served Mohammed and Abu Bakr on the way.

The three men thus made their way through the desert to Medina, after a detour that brought them to the shore of the Red Sea. After a journey of four days, they arrived at Quba, near Medina. Mohammed remained in Quba, as the guest of a local man, for two to four days, or longer according to some accounts. Those days were perhaps spent in making the last negotiations with the various sections of the population of Medina, so that Mohammed would able to enter the city itself as a guest protected by the whole Medinian community. At last (according to the most widely accepted version, on Friday September 28, 622) Mohammed left Quba and riding on his camel, proceeded to Medina.

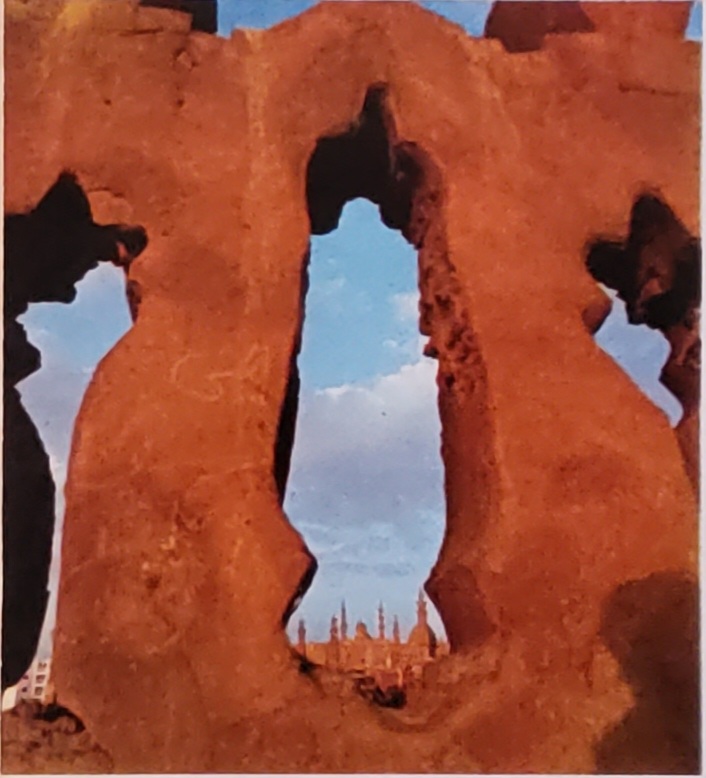

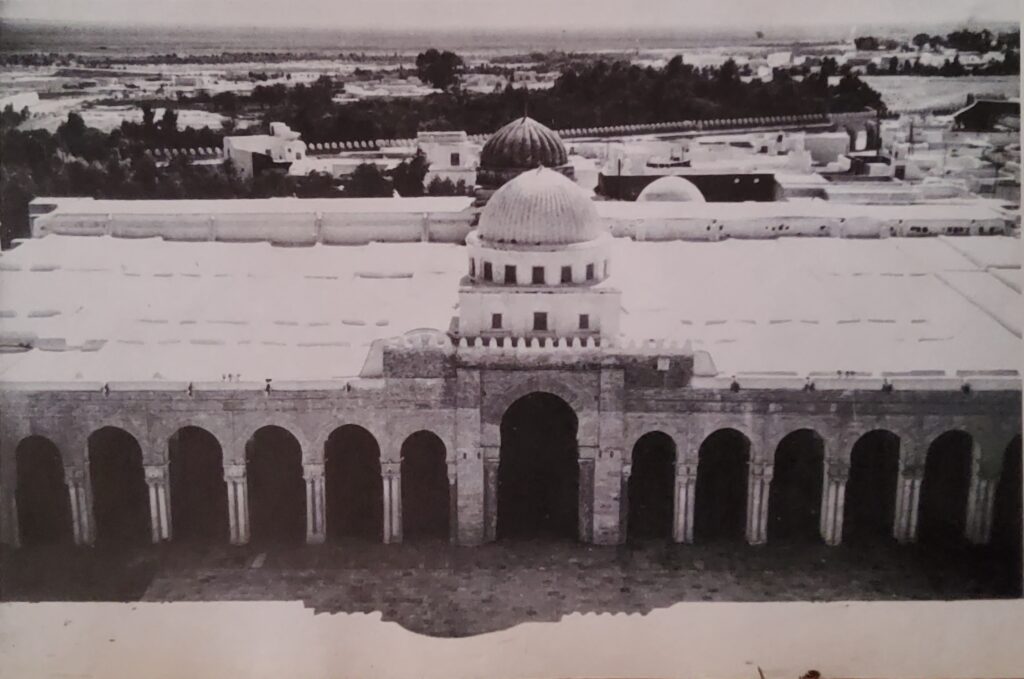

In one version of the legend, the various clans of Medina through whose quarters Mohammed made his way, vied with one another in offering the Prophet hospitality. Mohammed left it to the divinely inspired decision of his camel to choose for him the place where he would stay. On the spot where the camel stopped, the place of worship — mosque was to be built. It was a covered space with a courtyard. Rooms for Mohammed and his four wives adjoined the courtyard and the land was bought from the guardian of the orphans to whom it belonged.

Mohammed was thus established at Medina and the opportunity was given to him for proving himself as a statesman, as he had earlier proved himself a religious leader at Mecca. He proved equal to the task. During the remaining ten years of his life, he accomplished deeds for which his first fifty years had scarcely prepared him; those latent powers rose to the occasion. The Prophet was armed and he showed, in addition to his gift of spiritual leadership, the great astuteness and lack of scruple of the politician.

First, he firmly established his position as the political head of the community: strict obedience “to God and his messenger” was demanded. The messenger, Mohammed, became the actual ruler of a theocracy.

During the first years following the Hegira, the war with the Meccans took up most of the energies of the new Moslem state. Opportunities to get rid of the Medinian opposition, branded as the “hypocrites” and the Jewish tribes, who were either expelled or massacred, were not missed.

The Fall of Mecca

Soon, however, Mohammed’s ambitions went far beyond defending the Moslem refuge in Medina; his new aim was to subject the Arabian peninsula to his rule. Mecca itself was conquered in 630, eight years after the Hegira. Although Mecca’s pagan sanctuaries were incorporated into the system of the new religion and Mohammed’s birthplace with its holy Kaaba became the religious center of Islam, the capital remained at Medina. The Bedouin tribes were subdued by force or diplomacy; and by paying the “‘alms-tax,” these nomads acknowledged the supremacy of the Prophet, even if their religious fervour left a great deal to be desired. Thus, within ten years, the anarchic tribal society of the Arabian peninsula was organized into the semblance of a nation — in itself a stupendous achievement.

Did the Prophet’s ambition embrace even wider horizons? Had he, whose mission had originally been the call to preach to the Arabs, hitherto deprived of prophets, come to think himself the bearer of a message to mankind at large? If so, did he contemplate, as a corollary, the conquest of lands outside Arabia, after having conquered Arabia itself? Before his death in 632, there were skirmishes on the frontier region between the Hijaz and the Byzantine Empire, but it is uncertain whether they were considered as the preliminaries of any large operations. In general, it is difficult to give any definite answer to the question about the Prophet’s views of the outside world. If he had any extensive plans, he died without having the chance of embarking on their execution. It was his successors or Caliphs, who founded the Islamic Empire and governed it first from Medina, then from Damascus and then, from the newly founded Baghdad.

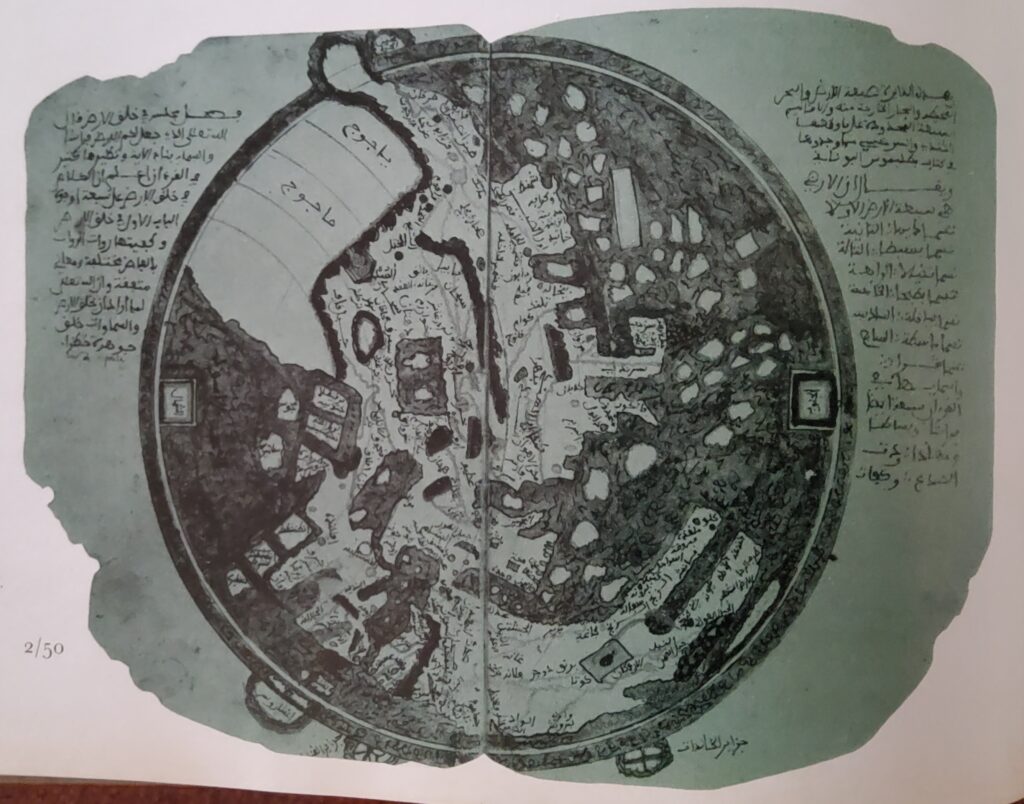

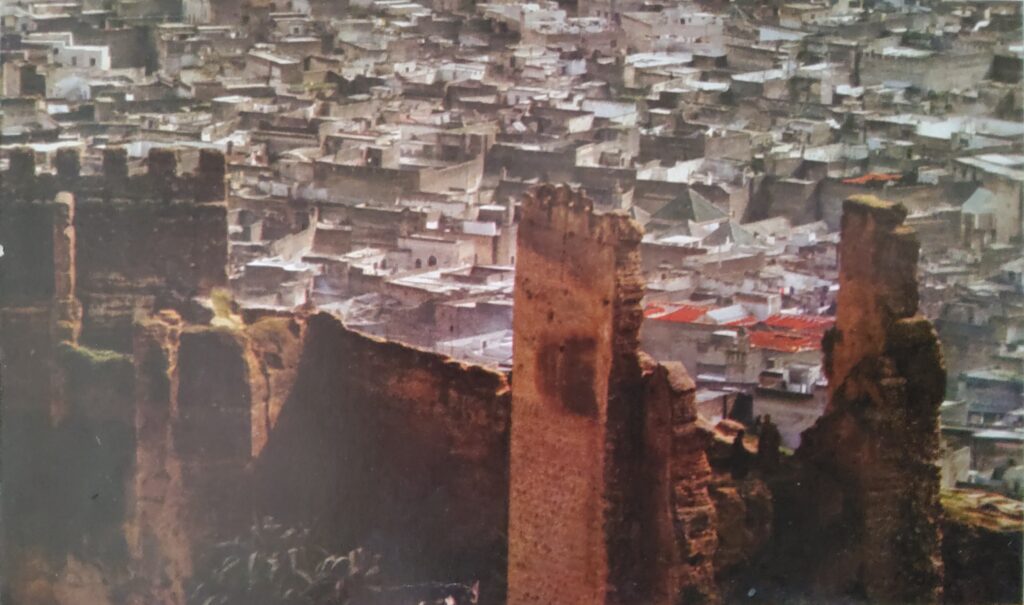

The Islamic conquests, whether they were planned by Mohammed as a further step in the succession of events inaugurated by the Hegira, or were rather the result of chance successes being exploited and then energetically directed by the Caliphs of Medina, changed the face of a large part of the earth. Within a few years, the Persian Empire of the Sassanids, was overrun and such important provinces of the Byzantine Empire as Syria and Egypt, followed soon by North Africa, were incorporated into the Islamic Empire. At the beginning of the eighth century, a second wave of conquests added Transoxania, the Indus valley in the east and Spain in the west. They gave Islam roughly the geographical extent it maintained, until the eleventh century. (At that time, small losses of territory in Spain and Sicily were compensated by large increases in central Asia, India and Anatolia.) Provinces that had formerly belonged to separate states and civilizations were now united within a new empire, that developed its own civilization. The political and cultural map of western Asia and the Mediterranean basin had been remade.

For a century and a half, the new Islamic Empire was a centrally governed state, headed by the Caliph, Mohammed’s successor as political ruler, but not his successor as prophet. Even after the caliphate began to disintegrate, it still remained a powerful structure for another century and its ghost, haunted the Moslem world long after its real might had disappeared. The office of Caliph was a peculiar creation of Islam: it grew naturally out of the particular circumstances in which the Moslem community found itself, after Mohammed’s death. In contrast, administrative methods were largely taken over from previous empires and the bureaucratic system, continued the secular traditions of the conquered lands.

The basis of the new Islamic civilization was provided by the economic and social unity of the world it conquered and this unity lasted, even after the disappearance of the political state. Commercial traffic passed easily through the vast tract of land between Transoxania and Spain and the same (or almost the same) currency was employed; this greatly promoted trade — and with goods travelled, social and cultural patterns. Not only merchants, but also learned men, traveled from one end of the Muslim world to the other and they spread a common form of education and culture. Islamic civilization did not grow out of nothing, it assimilated elements of different character.

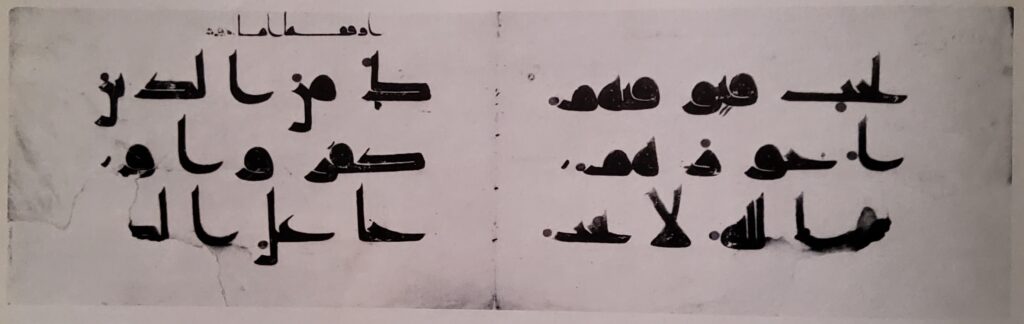

The Islamic religion itself, the main cementing factor in the new civilization, owed a great deal to preceding religions, chiefly Judaism and Christianity. The borrowings however, were used in an original manner and the new religion was more than a new combination of existing elements. Both religious and secular literature, was expressed in the Arabic language and whilst the vernaculars of the different provinces survived in spoken use, everything from the simplest letter, to the highest literature, was written in Arabic. The Koran, containing the text of the prophecies, pronounced by Mohammed in Mecca and Medina, was the first piece of Arabic literature committed to writing, but it was not this fact alone that gave the Arabic language its religious significance. The whole many-branched theological literature, created by Islam, was in Arabic and was carried by traveling scholars all over the Islamic world.

Secular literature was in the first instance, based on the traditional oral literature, produced by the tribal society of pre-Islamic Arabia. Its traditional heroic lyric poetry and prose stories, were adopted by Islamic civilization; after having been the functional expression of tribal society, this whole literature reduced to writing by philologists became the foundation of the humanistic education of urban Islamic society, in the same way as Homer had been the bible of Hellenism. In the Islamic period there developed a courtly urban poetry which, however alien in spirit to the ancient poetry of the desert, was in its style, deeply indebted to it. Thus the legacy of pre-Islamic tribal Arabia, was one of the component elements of Islamic civilization. The other elements came from the ancient civilizations of the territories, incorporated into the empire.

The Conversion of the Persians

The Persians, with an imperial history of more than a thousand years, possessed a strong national sentiment. This tradition had been closely, but not inextricably, connected with their national religion, Zoroastrianism; and even after their conversion to Islam, the Persians did not renounce their attachment to their secular national traditions. While using Persian as their vernacular, they too wrote in Arabic and adopted the Islamic culture expressed in Arabic; but they introduced into that culture many elements of Persian ideas on statecraft. It was mainly government officials of Persian extraction who were responsible for the promotion of Persian ideas within the world of Islam. Some scientific treatises were also translated from Persian into Arabic; and so were some Indian books, either directly, or through Persian mediation.

In the scientific field, however, the main contribution came from Greco-Roman antiquity. The Christian subjects of the Islamic Empire were in the possession of a large body of scientific and philosophical literature, either in the original Greek or in Syriac translations. (Syriac was the Aramaic dialect used as a literary language by many Christlans in the eastern provinces of the Roman Empire, as well as in Persia.) Christian translators rendered these books into Arabic, in which form they became available also to the Moslems, who never mastered either Greek or Syriac. At first, their interest in Greek science was mainly practical: they needed physicians to cure them and astrologers to advise them on how to arrange their affairs under the most favourable influence of the stars. Soon science and philosophy attracted them for their own sake. Nor were they satisfied with passively studying the writings of the ancients — but reorganized and sometimes even improved upon them.

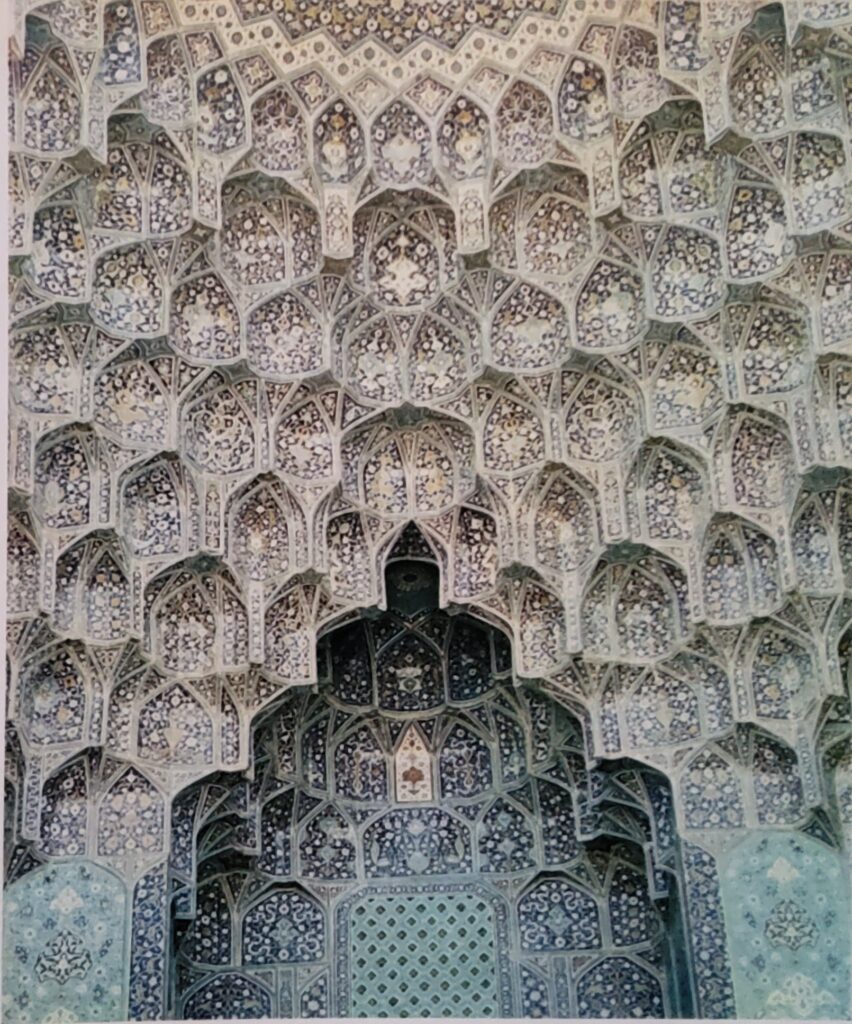

In general, it would be as wrong to consider the Islamic civilization a mere juxtaposition of existing elements, as to consider Islam a mere adding up of Judaism, Christianity and Arabian paganism. By a strange alchemy, the old elements were so fused together and transformed that something quite original resulted. Thus, while Islamic art owes a great deal to the traditions of the previous civilizations, it has a strong character of its own. One of its most individual aspects springs from the prohibition placed by Islam on iconographic representation, with the result that this is virtually nonexistent.

It is obvious, therefore, that Islamic civilization did not come into being in one moment. Nor was it static; it remained — as does everything in history in continuous flux. The reemergence of Persian, as an Islamic literary language in the tenth century, for example, tended to give the eastern part of the Islamic world a character different from the western part, where Arabic was used exclusively. The foundation of the Islamic Empire — a direct or indirect consequence of Mohammed’s Hegira, gave rise to a new civilization. Islamic religion is still very much alive. It is, however, more than doubtful whether the remnants of Islamic civilization still exists; but for twelve hundred years or so, it has undoubtedly shaped the life of a considerable portion, of the human race.