Henry IV stood barefoot in the snow, for three days in January, 1077, outside Canossa castle, waiting to see Pope Gregory VIl and to beg him to lift the dreaded sentence of excommunication. Henry’s action was the culmination of a conflict between Church and State that had been brewing for centuries. Medieval rulers had come to regard their bishops merely as feudal nobles who were expected to fill their proper roles in the functioning of their kingdoms, but some of the clergy wished to emphasize the religious office of bishops by removing them from the responsibilities and the privileges, of civil government. The Pope’s victory in forcing Henry to humiliate himself at Canossa did not resolve the conflict, but it did help play down the sacred character of kingship and thus paved the way for the creation of modern secular states.

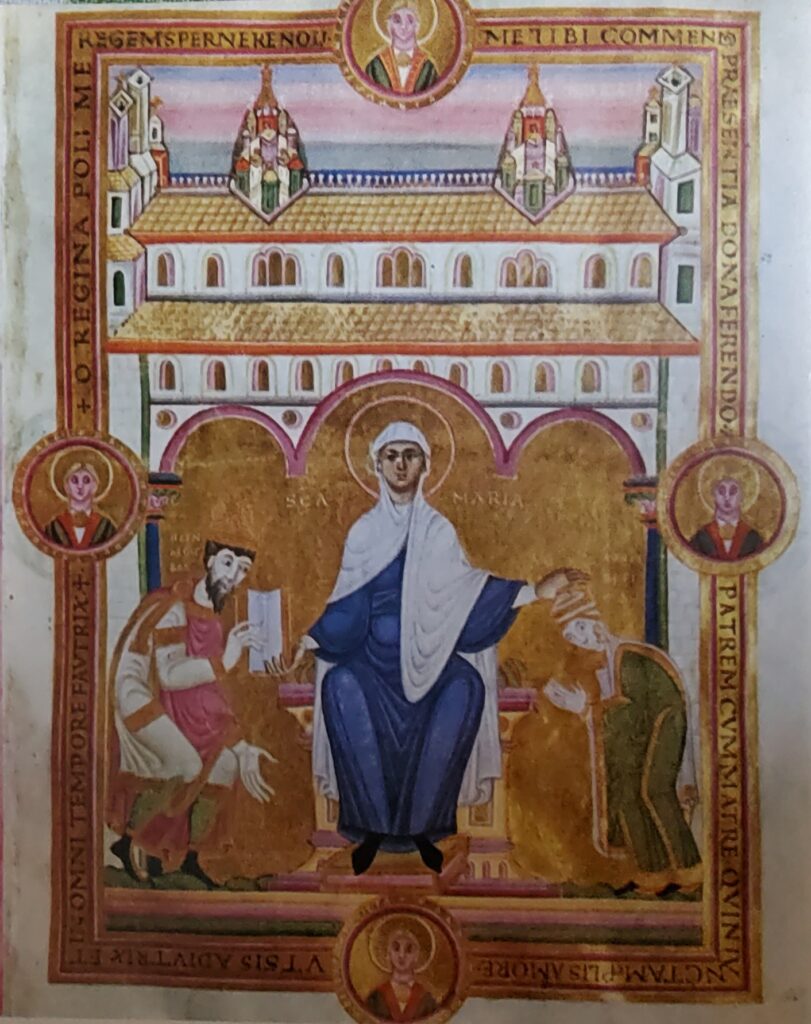

In January of 1077, Pope Gregory VII was residing at Canossa, a castle on the northern slopes of the Appenines owned by the Countess Matilda of Tuscany. On the 25th day of that month, the Emperor Henry IV appeared in front of the castle as ordered, “and since the castle was surrounded by three rings of walls, he was allowed inside the second ring. His entourage had to wait outside. He stood divested of his royal garments, without the insignia of his dignity, without ornaments of any kind. He was barefoot and fasted from morning to the evening in expectation of the sentence of the Roman Pope. He had to do this for a second and a third day. On the fourth day he was allowed to appear before the Pope and was told that the excommunication would be repealed under certain conditions.”

The chronicler to whom we owe this moving description, Lambert of Hersfeld, then tells of the conditions. The Emperor was to submit himself to a thorough judicial examination to determine whether he was to keep his domains; he was to sever his personal relations with certain evil men whose advice had led him to the point at which, a year before, the Pope had excommunicated him. At this, the Pope said Mass and during the office he declared that in order to prove his innocence of countercharges that had been leveled against him (they ranged from murder and adultery to heresy and simony) he would eat one half of the Lord’s body and hoped he would be struck down dead if he were not innocent.

Having done so, Gregory invited the Emperor to do likewise, but Henry was obviously uncertain either of his own innocence or of the effectiveness of the test — it is impossible to say which. Caught unawares, we are told, he blanched and stammered and sought excuses and eventually begged the Pope not to insist, pleading that since the men who had accused him were not present the test could not possibly be significant. Gregory was won over, the tense moment passed and then the Pope invited the Emperor to share his breakfast. Henry must have sighed with relief but when the news of his reconciliation with the Pope was announced to the Etalian bishops assembled outside the castle, there was a violent commotion. These men had supported Henry because they were jealous of the Bishop of Rome. They now felt let down and threatened to depose Henry and lead his son, who was still a minor, to Rome and there unseat the Pope. Only with the greatest diplomacy was this outburst of indignation suppressed. In the end, they all agreed to wait for the assembly at which Henry was to place his case before the magnates of the Empire and wait upon their decision.

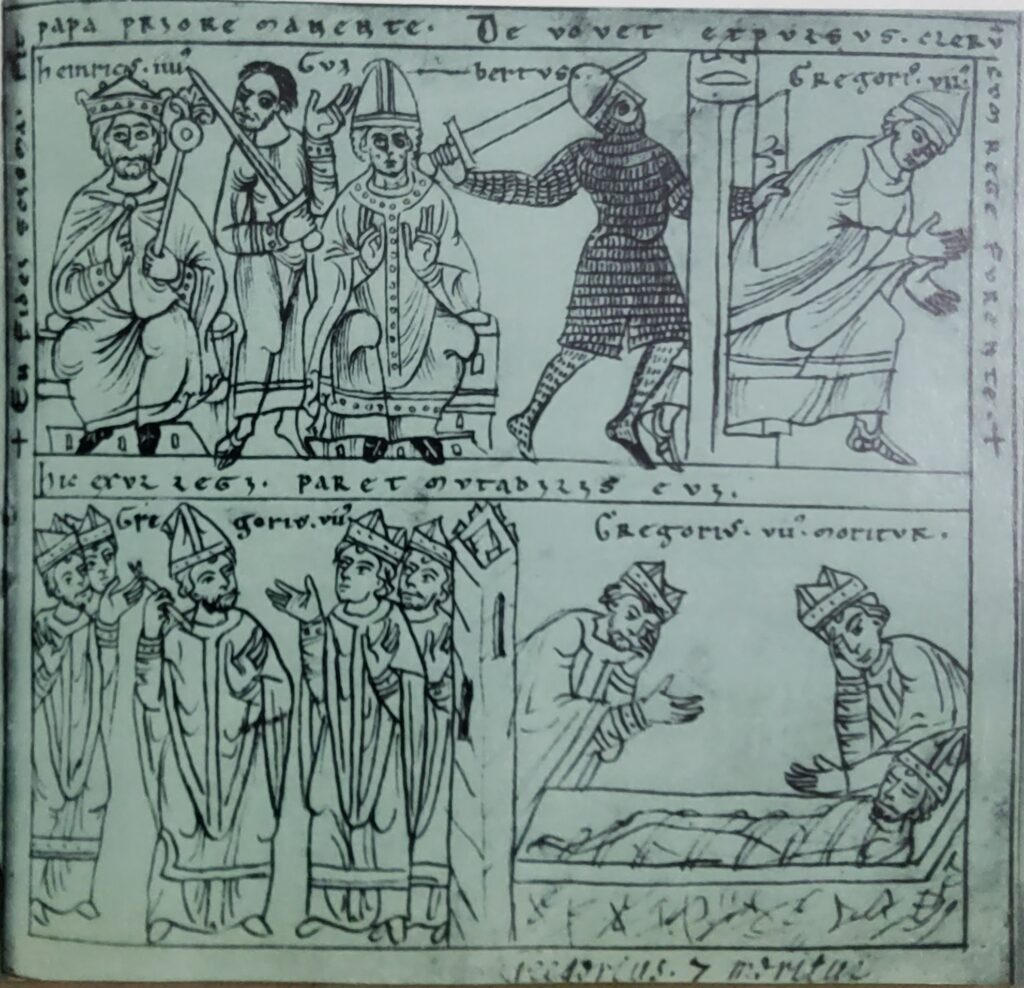

The day of Canossa appeared to be a great triumph for the papacy and as such, has become almost proverbial. In fact, the Emperor got the better of the Pope. By doing penance, Henry obliged Pope Gregory VII to lift the excommunication and thus removed the one great obstacle that had stood in his way. Henry could now rally his supporters and by 1081 he was able to march an army into Italy, appear before Rome and after lengthy battles, install there a Pope of his own choice, Clement III, the Archbishop of Ravenna.

Pope Gregory held out inside the castle of Sant’ Angelo; but Henry was crowned Emperor in Rome on March 31, 1084 by his own Pope. Eventually the Normans from Sicily under their king, Guiscard, came to Gregory’s rescue. The fighting in Rome was severe and the city suffered grievously, but no decision was reached and eventually the Normans withdrew, taking Gregory south with them in semicaptivity. He died in Salerno on May 25 of the following year, breathing his last with a somewhat ironical variant of verse 8 from Psalm XIV: “I have loved righteousness and hated iniquity; therefore I die in exile.”

The clash between the Emperor Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII was the culmination of a long development that, but for the fiery intolerance of the Pope and the youthful temper of Henry IV, might have had a completely different ending.

Charlemagne’s idealism fades

The conflict between Church and State had been developing for centuries. One of the most far-reaching effects of the barbarian invasions of the Roman Empire in the fifth and sixth centuries A. D., was the blow to the Christian churches. The invaders were all Christians, but conversion to the new religion had been for them a mass movement; they followed their king. It had not been associated with spiritual regeneration, nor had it been an answer to a spiritual need. The barbarians needed a new communal ritual to replace the one they had lost when they had left their homesteads. Furthermore, the economic decline of the Roman Empire, which had in fact preceded the invasions, but which was further hastened by them, had essentially meant a decline of urban life and culture.

With the advancing ruralization of the imperial territories, there disappeared also the economic and administrative basis of the churches. The urban Christian communities and their bishops declined in number and importance. By the seventh century, bishops were no longer churchmen; they were the owners of large landed estates. They came to share the customs and outlook of the landed magnates and as such, they were soon rendering military service to kings. All this was not so much an expression of declining piety as it was the result of the economic and social changes that took place during the early Middle Ages. With the centres of religious organization dispersed, educational opportunities — essential to a religion based on the knowledge of the Bible and a complex liturgy — declined sharply. Christian pastors of these centuries, in their simple-minded dislike of the pre-Christian, pagan cultures of Rome and Greece, lent an active, if unwitting, hand to that decline by decrying education — for to them, education usually meant the study of pagan literature.

The short-lived idealism of Charlemagne (768 – 814) had no real lasting effect. In the course of the tenth century, man’s innate yearning for transcendence, for spiritual edification, for ascetic morals and ethical guidance began to reassert itself. There emerged, at first, in the central parts of the old Carolingian Empire, in the so-called Middle Kingdom comprising the present-day Netherlands, Lorraine and Burgundy, a new monastic movement led by the monks of Cluny. This newly reformed branch of the old monastic order propagated the idea that the religious life was one of seclusion, dedicated wholly to prayer. The influence of Cluny’s example was enormous. A vast number of daughter houses were established in Central Europe and hundreds of new recruits for religion were enlisted. The reform movement also led to the reorganization of old religious houses. By the early eleventh century, a wave of revived religious activity was sweeping across Europe.

One of the innovations introduced by Cluny was the regulation that a reformed monastery should be exempt, no matter where it was situated, from the control of the local bishop. Bishops being potentates, this was an essential factor in the success of the reform movement. By the eleventh century, abbots of both reformed and not so reformed houses, such as Suger of St. Denis, Poppo of Stablo and Odilo of Cluny, tended to replace bishops as the trusted advisers and scribes of kings and emperors. The reason was that kings soon discovered they could benefit from this new movement. If the inhabitants of their kingdoms could be imbued with religious fervour, the kingdoms would receive a spiritual sustenance as a result.

The first monarch to recognize this was Henry III of Germany (1039-56). Henry’s relations with the magnates of his kingdom were unhappy. In 1047, he was almost assassinated while visiting Adalbert, the Archbishop of Bremen and Hamburg. Adalbert was a very able administrator and had sought to turn his archdiocese into a territorial state. The Saxon nobility was highly suspicious of such non-feudal behaviour and when they discovered that Adalbert had Henry’s full support, they conspired against Henry. Hence, the attempted assassination. Similarly, Conrad, Duke of Bavaria, angered by Henry’s close association with the episcopate of Bavaria, rose against him. The rebellion was suppressed, but Conrad escaped and in 1055 organized a major conspiracy to assassinate Henry. Another long-standing rebel was Godfrey, Duke of Lorraine, whom Henry prevented from taking over the whole of his father’s inheritance. Godfrey was not content with half and eventually married an Italian heiress in order to compensate himself for his loss of power. The Italian threat which thus emerged, was considerable.

Faced with such threats to his authority, Henry turned to the Church for support of his throne. He decided not only to throw his weight behind the reform movement of the Church, but also to provide it with the administrative framework and centralized direction it would need in order to become truly universal. A shrewd statesman, Henry decided to introduce reform into the see of Rome, the bishopric which was the first see of Christendom.

The bishops of Rome, during the century and a half preceding the reign of Henry III, had had neither desire nor opportunity for exercising the functions of the papacy. The office, the leading governmental institution in the city, had become the coveted prize of the aristocratic clans in and around Rome. These parties had fought over the papacy and had removed successful candidates by murder or blackmail. The incumbents who were willing to play along were always scions of these families, their minds and ambitions more on local power than on the welfare of the Church—of which most of them knew only by hearsay and which interested them little, if at all.

In 1046, Henry III decided to intervene. He held a synod at Sutri, deposed the reigning Pope Gregory VI, declared several other claimants to the see also deposed and caused, in quick succession, a whole series of “foreign” popes to be installed in Rome. All those who took office under imperial patronage were ardent reformers and came from abroad. Thus the spirit of the reform movement captured the city of Rome, for with the new popes there also appeared a large number of foreign clergy, who supported the reform movement.

With this action, however, Henry III also introduced the possibility of conflict between Empire and Church. His objection to the deposed popes was based on the principle that simony was an evil practice. No man should be allowed to assume a spiritual office in return for material considerations such as money payments or promises of political influence. The reform party was only too happy to seize this opportunity, to capture Rome and to spread their ideas and practices from the central see of Christendom. At the same time, the fact that they owed their position to the Emperor raised an irksome question. It was becoming more and more clearly the objective of the reform movement to make the Church independent of laymen and to see to it that in the Church none but canon law prevailed. Insofar as the reform party owed its capture of Rome to the Emperor, the Church could hardly be said to be independent.

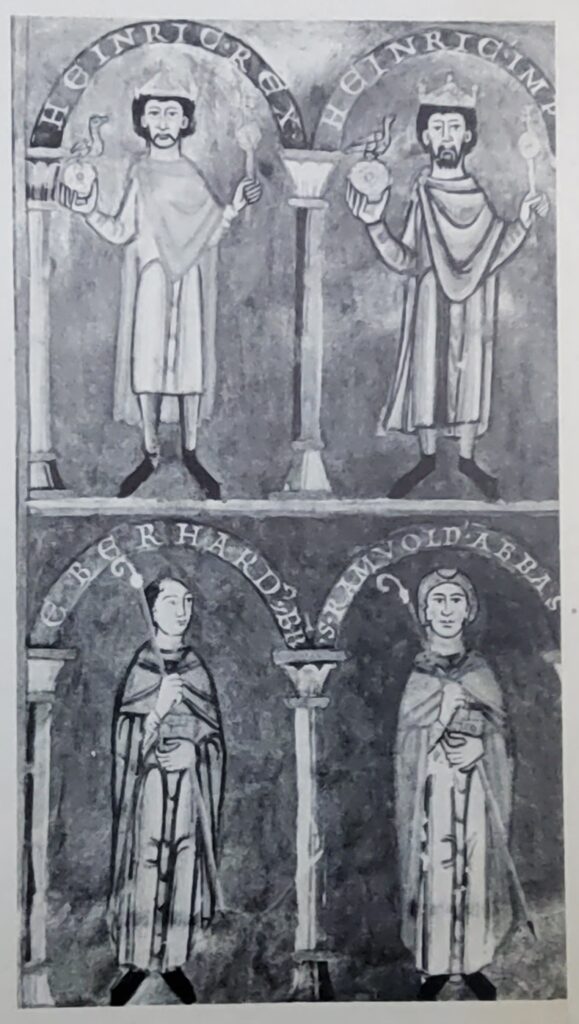

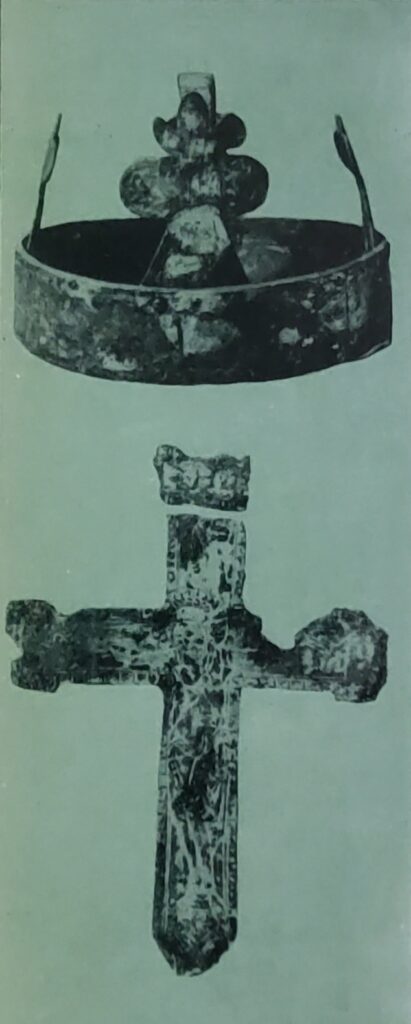

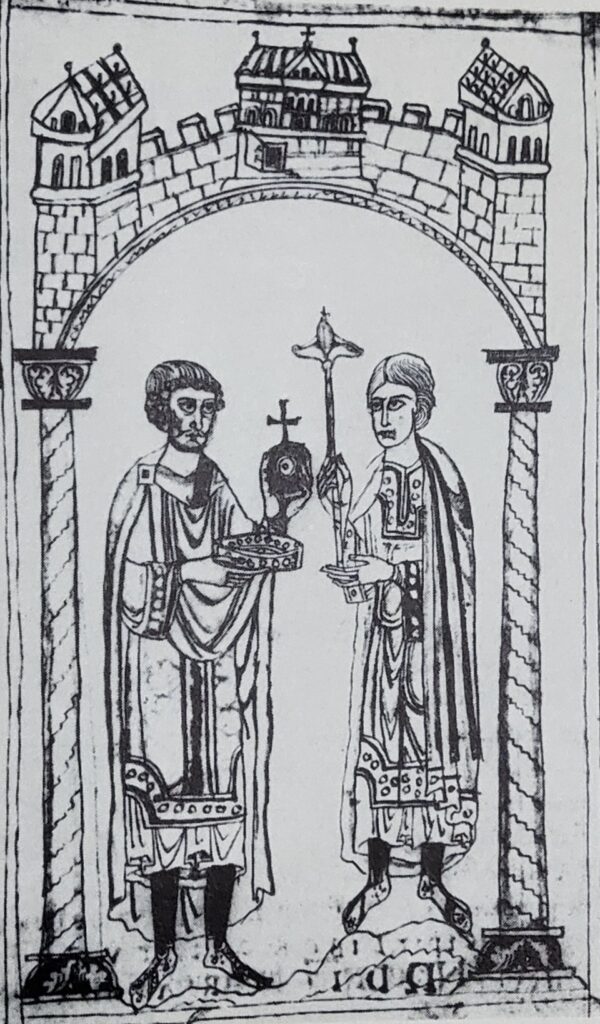

Nevertheless, this was an issue which, given time and thought, could have been settled amicably. After all, the Emperor (and, for that matter, many a king) was not exactly a “lay” person. He was elevated to the throne by unction and wore garments of religious significance—not the least significant, his splendid crown. True, the crown was perhaps only a special kind of helmet, but its splendour of gold and precious stones made it into a symbol of the sun. An anointed ruler was another David and had divine sanction. His ascendancy in the Church and his protection of religion need not therefore necessarily be construed as an act of lay interference.

Under Pope Leo IX (1049-54), the reform movement made rapid progress. He brought a large number of his friends and associates to Rome and spent much time traveling. He used his authority to remove simoniacal bishops and abbots; and granted the vacant sees to adherents of the reform movement. The presence of his supporters in Rome created an institutional background to the reform movement by surrounding the papacy with a suitable clergy who would be likely to elect a suitable successor. A few years later, Pope Nicholas I, formally created the College of Cardinals to ensure an orderly election by the presence of an advisory body. Both the prestige and the influence of the papacy rose enormously during this decade and is reflected in the publication of the new collection of canon law, the so-called Collection in Seventy-Four Titles, which gave great prominence to the legal prerogatives of the see of St. Peter.

The death of Henry III in 1056 was a blow to the movement. He was succeeded by his son, Henry IV, a minor. During the necessary regency, Henry became so frustrated and depressed by the unpleasant forms of tutelage exercised over him, that he failed to develop a prudent and balanced outlook, where a prudent and mature assessment of the situation was required. The close cooperation between Henry III and the reforming party was based on mutual esteem. It had led of necessity to the strong assertion of the primacy of the see of Rome. To assert such primacy in regard to the Church was one thing; a personal clash and a rivalry between Pope and Emperor, could easily turn the question of primacy into one of who was master, Emperor or Pope. Although there were several ambiguous pronouncements on this question, the matter had never been settled. There had been occasions of conflict that in turn had given rise to further ambiguous pronouncements like the famous statements about the two swords one wielded by the Pope, the other by the Emperor, or like the statement that Church stood to State like soul to body. There had never yet been a confrontation and everyone had probably preferred, a merciful vagueness to any definite answer.

Henry IV came of age in 1065 and spent the first ten years of his reign subduing the rebellious Saxon nobility. In 1075, he thought he was at last firmly established. In that year there was a dispute over the succession to the archbishopric of Milan. Henry and Pope Gregory VII, supported rival claimants. When Henry refused to drop his candidate, he received, on New Year’s Day, 1076, a letter from Gregory, in which he was tactlessly reminded that he owed obedience to the Pope. Henry, aware of Gregory’s somewhat tenuous hold over the city and people of Rome; and made confident by his recent triumph over the Saxon nobility, was determined, after years of frustration, to use the full force of his authority. He wrote back to Gregory, charging him with all sorts of crimes and ordering him to relinquish the papacy. He also invited the people of Rome to rid themselves of their bishop. Gregory replied by excommunicating and deposing Henry.

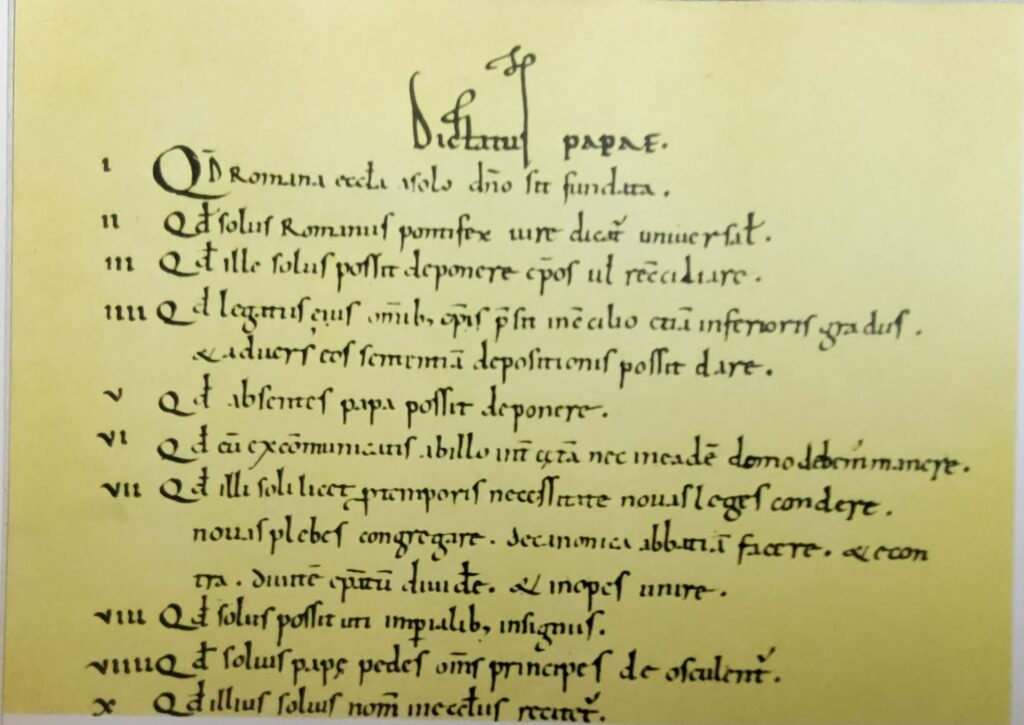

This situation had been brought about by the temper of the two protagonists. There was some precendent for Henry’s deposition of an unworthy Pope. There was none for Gregory’s deposition of an unworthy monarch — he was clearly, behaving in a revolutionary manner. However, tvhere was needed little stretching of the major points of the reform movement, to include among the prerogatives of the Holy See, the right to depose kings. Gregory had fortified himself in advance by adding a formal statement of his rights, the Dictatus Papae, to his register. The gist of this manifesto was that the Roman bishop alone, not the Emperor, had universal power. The kings of Christendom, with the exception of William the Conqueror, naturally became wary of Gregor, but needless to say, the nobility of Germany seized the opportunity of the Emperor’s difficulties and rebelled against him. Formally excommunicated, Henry could do nothing. So he humbled himself at Canossa.

Canossa by itself did not become a turning point: Gregory, as we have seen, died in exile; Henry never quite managed to restore peace in his empire. The disputed issue of the primacy of Pope or Emperor, was never resolved, but as a result of the long war unleashed by Gregory’s invitation to rebellion in Germany, the monarchy became weaker and weaker over the next half century.

The Papacy states its rights

For the papacy, the consequences of Gregory VII’s actions were more far-reaching and in the long run, equally fatal. Since no subsequent Pope could disavow the reform movement and since the spirit, if not the letter, of the Dictatus Papae had become built into the reform movement as a result of the clash between Henry and Gregory, the papacy was launched on a course in which superiority over temporal powers, was explicitly claimed from time to time.

Probably the nascent states of late medieval Europe, as well as the princedoms which sprang up within the confines of the old Empire, were indirectly the ultimate beneficiaries. For even if papal superiority over secular rulers could not be clearly vindicated, the status of kingship and of the Empire came to be desacramentalized. The unction became less and less of a sacrament; kings became less and less new Davids. When the number of sacraments was officially defined as seven, at the Lateran Council in the early thirteenth century, the royal or imperial coronation was not one of them. Cut down to size as secular magistrates; less and less frequently thought of as quasi-priestly rulers and divinely appointed kings, the new monarchs of Christendom settled down to the task of pragmatic government and utilitarian administration. As such, they all learned to treat their clergy, high and low, as their subjects. They mastered the techniques of taxing them and making the Church in their lands into departments of state. For good or ill, the modern secular state could not have evolved, had the popes not taken the initiative towards making kingship less of a sacred office.