Hugh Capet was coronated in 987 and with that, began the French dominance of Europe. During the eleventh century, a view of world history is dominated by the splendours of the Sung empire in China. Founded in the last decades of the previous century, it reached a peak during the eleventh century and that entitles it to be regarded as one of the most brilliant epochs, in the history of civilization. The European stage, is commanded by the prestige and apparent power of the German empire, founded by Otto I and ruled over by his descendants. Both the ambitions of the emperors and the ever-growing power of the great vassals contributed, with other causes, to a decline which even the reign of the great twelfth-century emperor Frederick Barbarossa, did not reverse. By 1200, power in Europe was slipping from the hands of the German emperors and was taken up by the central kingdom of France.

The emergence of France as the dominant power in European affairs, during the high Middle Ages, was by no means a foregone conclusion. To observers of the coronation of Hugh Capet as king in 987, it must have seemed a very unlikely event. It is worth remembering how slow this rise was. Not for another two and a half centuries — centuries of constant struggle — was the French ascendancy to become obvious.

French Monarchy from Hugh Capet to Louis VI

At the time of his coronation, Hugh Capet was perhaps the most important man in France. His family, founded over a century before by Robert the Strong, had already provided two kings during the troubled years of the later Carolingians. His lands, grouped around the important towns of Paris and Orléans, were strategically wellplaced; among his feudatories, were some of the most powerful men in the kingdom; and he himself enjoyed the support of the Church, to which in large measure he owed his election. Though there were many houses with more extensive possessions and at the opening of the eleventh century, the map of France dramatically reveals the considerable threat of the provincial powers, with which the Capetians had to contend.

In the south, the duchy of Gascony and the county of Toulouse were remote; to the north of them stretched the great duchy of Aquitaine, controlled by the house of Poitou; to the northwest, brittany, never subdued by Charlemagne, maintained its ancient independence; still farther north was the powerful duchy of Normandy, which was soon to be transformed into the strongest province of France by the efforts of Duke William. These were the main territories; but as the century advanced, the lands between Normandy and Aquitaine were gradually mastered by the small but dynamic county of Anjou.

Throughout France, the great lords who pressed upon the king, were in their turn continually struggling to contain the ambitions of a mass of lesser vassals. Nowhere else in Europe did the full effects of feudal land tenure make themselves felt so rapidly as in France. Amid this multitude of magnates, each already striving to maintain his position within his duchy (the dukes of Burgundy, for example, failed and themselves became little better than bandits), each aimed to strengthen his position at the expense of his neighbours. The kings of the Capetian dynasty were in territorial terms, one of the weaker groups in the kingdom. Their advantages were nebulous but, as it turned out, important. The change of dynasty from Carolingian to Capetian did not weaken the respect in which the kingship itself was held. Well aware that their hold on their own vassals was often little stronger than the ties of feudal obligation, the great feudatories were eager to acknowledge the theoretical supremacy of the king from who their own authority ultimately derived.

The king, then, was the suzerain of all and beholden to none, save God. Second, the monarchy enjoyed and cultivated the support of the Church, an element to be of increasing importance as the century went by. Third, the dynasty, by a remarkable demographic feat, was able to provide an unbroken line of male descendants for three and a half centuries. Each Capetian was careful to have his son crowned king before his own death. The ancient principle of election, never forgotten in Germany, was gradually, if only by force of custom, displaced by that of hereditary kingship.

Finally, the Capetians, unlike their Carolingian predecessors, were never greatly tempted to assert the full theoretical power of their office. They were content to devote their energies to making themselves absolute masters in their own domains and vassals.

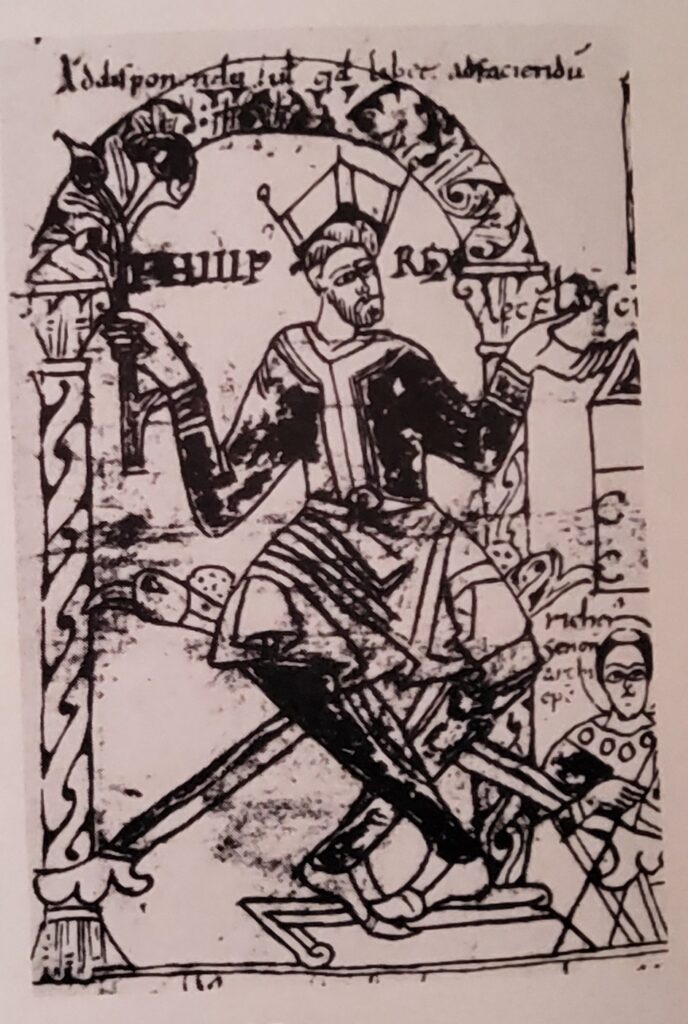

The kings had to tread warily. In the middle of the century, Henry I — attempting to preserve his position in the dangerous wars between his two great vassals, William of Normandy and Geoffrey of Anjou — shifted alliances between them and suffered two humiliating defeats at the hands of William. His son and successor, Philip I (1060-1108), showed more circumspection and wiliness in seizing his advantage at the most opportune moment. He managed to extend the royal domain with small but significant accessions and to draw some advantage for himself, from the civil wars which raged in Normandy between the sons of William the Conqueror.

The tide turns

It was during the reign of Louis VI, that the tide finally turned. After a century of acceptance, the Capetian dynasty, whatever its weaknesses, had become the focus of what may be regarded as a nascent national feeling. Louis VI, tireless in his efforts to put down the petty baronage within the royal domain itself and active in asserting his rights as king in France abroad, left to his son a country more firmly governed than ever before. More important still, by marrying the young prince to Eleanor, heiress of the vast lands of Aquitaine, he seemed to have supplied the French monarchy with a firm base from which to assert its control of the whole country. It is one of the tragedies of French history that the weak and monkish Louis VII, was unable to satisfy his passionate wife.

England before the Conquest

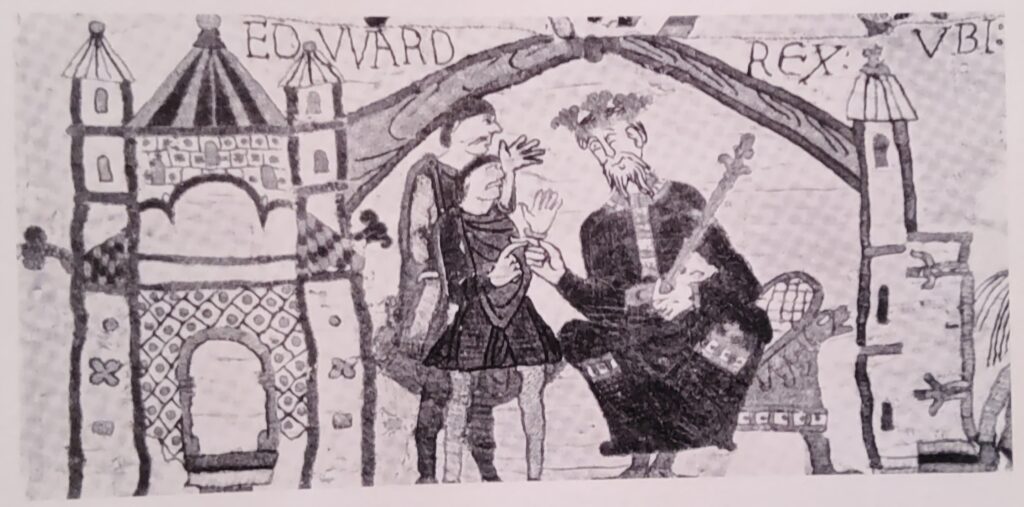

The empire of Canute the Great, King of Denmark, Norway and England, fell apart after his death in 1035. For England, his reign had been a period of peace and prosperity, but his sons were unable to continue the tradition of their father. In 1042, when the last of them died, the English recalled the senior surviving member of the house of Wessex from exile in Normandy. The son of Aethelred and his Norman wife, Emma; Edward was forty years old when he came to the throne. He had grown to manhood in a foreign land and he now found himself in a country where the great families, well-entrenched in the years after Canute, had little interest in a return to a powerful kingship.

Chief among these families was that of Earl Godwin, who was able to force the king to contract marriage with his daughter Edith. The marriage was merely a formality, for Edward seems to have taken a vow of celibacy on religious grounds. Despite a period of exile and disgrace, during which the king was able to consolidate the position of his many Norman friends and ministers at court, the house of Godwin returned in irresistible strength in 1052. That same year, Edward made an immensely unpopular move by promising the throne to his cousin, William of Normandy, a promise he did not have the power to enforce. Godwin, who died the following year and his sons, soon gained control of the apparatus of government. Thanks to Edward’s celibate life within marriage, there was no natural heir to the throne. All but one, of the remaining branches of the ancient royal house of Wessex had died out.

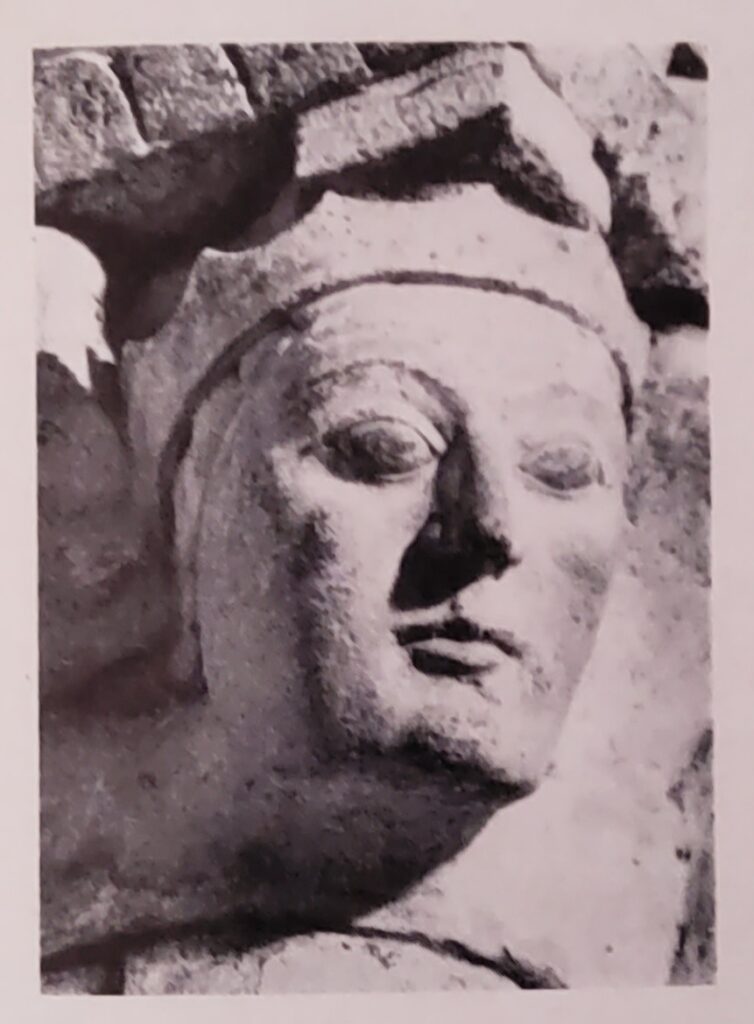

When King Edward himself died in January, 1066, he was succeeded by Harold Godwinson, elected by the Witan with the approval — so it was claimed — of the dying king. Revered during his own lifetime for his saintly character and in a later age, beatified and canonized by the Church, Edward the Confessor has as his enduring monument the Abbey of Westminster, which was his foundation and to which he devoted most of the last years of his life.

It is easy perhaps to write Edward off as a weak, ineffectual king and indeed the facts of his reign reveal him as lacking the wily and aggressive ruthlessness required of a successful monarch during the eleventh century. We should however, not forget the powerful position that the English earls had already built up by the time when the new king arrived from overseas to take up a taxing kingship, nor that Edward was then already past his prime. More important, it was Edward, who by his choice, gave William of Normandy his strongest claim to the throne. Despite the immense power and prestige of the hated Godwin family during the last ten years of his life, Edward never went back on that choice. In fact, he did all in his power to ensure its acceptance by his English earls, to whom the choice was so unpopular. Although it was undoubtedly coloured by hatred of the Godwin clan, Edward’s decision on the succession was a wise one for England. He chose as his heir one of the most effective rulers in a Europe, crowded with overmighty vassals and ineffective kings.

The Danegeld

One of the most remarkable powers of the English monarchy was that of levying a universal tax — called the “Danegeld” — on the population at large; and this was to provide a valuable source of revenue for the first Norman kings. Compared with any other state in contemporary Europe, except possibly the Empire, the England of Edward the Confessor boasted an administrative system and a monarchic potential second to none. It was a tool that the autocratic and gifted William of Normandy knew well how to use. When we add to these advantages the fact that by the very act of conquest, William was able to rapidly eliminate the powerful territorial interests of the earls and replace them with chosen men who owed their very position in England to him, we can see that the strength of the Norman English monarchy — so important a factor in medieval English history — was by no means fortuitous.

It was soon demonstrated that, despite the inevitable humiliations and brutalities attendant on conquest, the saintly Edward had chosen his heir with considerable shrewdness. Finally, it is worth noting that Harold, Edward’s successor, owed his kingship to election. Without the Norman conquest, England might well have found herself saddled with the divisive effects of an elective monarchy which, in the long run, was to destroy even the power of the mighty German emperors.