Constantine’s victory at the Milvian Bridge, ensures the spread of Christianity, throughout the Roman Empire. The Roman Empire, at the end of the third century A.D., was at the point of collapse. Struggles amongst rival emperors brought frequent civil wars, while barbarian hordes threatened the borders. Early in the new century, a soldier named Constantine proclaimed himself Emperor and immediately set out to make good his claim in a series of campaigns that took him, by the summer of 312, to the edge of Rome. Constantine had a momentous vision — a vision in which he was told, that he would conquer in the sign of the Cross, the symbol of the despised young Christian religion. The warrior’s subsequent victory at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge won for Christianity, an end to persecution and recognition as a legal religion.

The third century of the Christian era was a grim, squalid age. For centuries the Roman Empire had maintained peace and fostered prosperity throughout the Mediterranean world, but now it was in decline. Stable central power had collapsed, as a succession of would-be warlords marched their predatory armies up and down the Empire, striving to seize power or to hold it against their rivals. Sometimes the legions actually put the Empire up for auction. At one and the same time, there might be three or four self-styled emperors. None of them lasted long.

Meanwhile, the lot of the common man became ever more miserable and uncertain as cities were sacked, the countryside ravaged and wealth confiscated to pay the rapacious soldiery. Debasement of the currency and interruption of trade routes led to galloping inflation. The urbane, sophisticated culture of the cities sank under a rising tide of philistinism and peasant brutality, as men jettisoned their intellectual baggage in the cheerless struggle for survival,

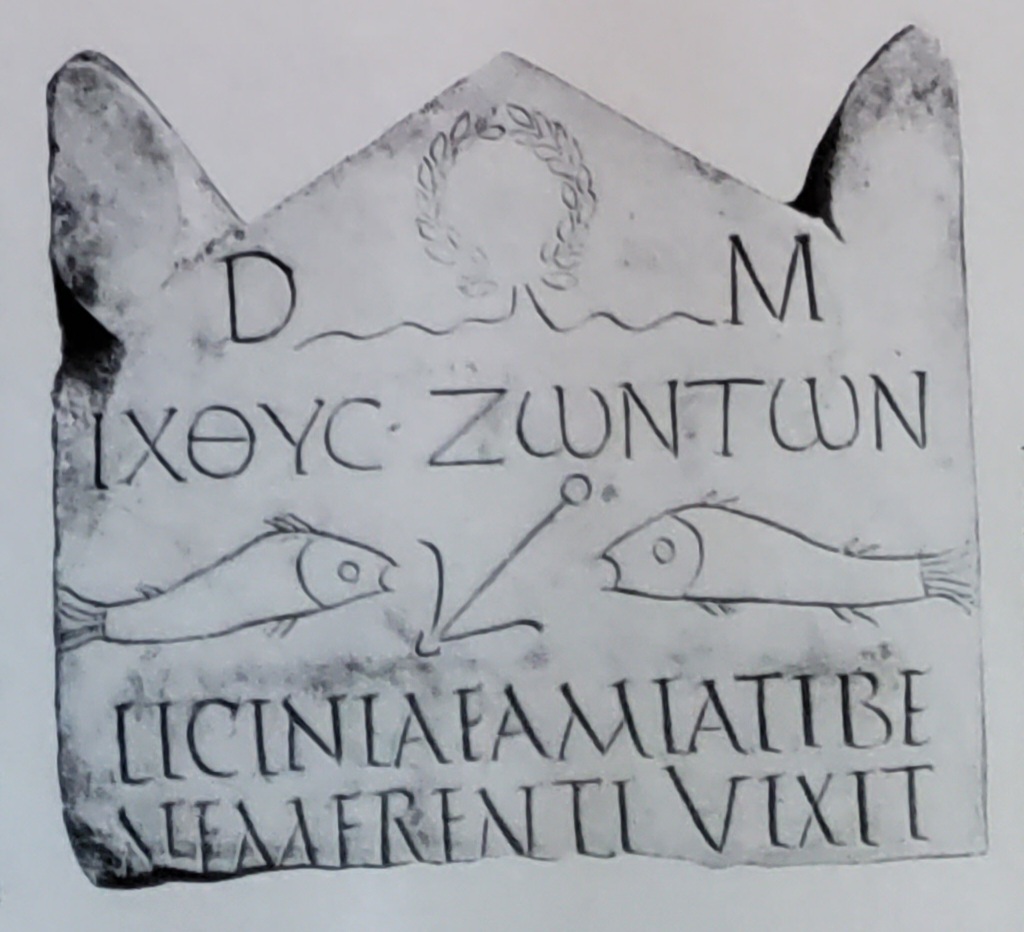

Faced with the uncertainty of life, people turned to magic and divination in attempts to penetrate the inscrutable will of the power that ruled the universe. Or they embraced religions that promised salvation in the next world to those who performed the right actions or held the right beliefs. A single, all-powerful god more and more replaced in men’s minds, the consortium of Olympians. Some called him Apollo; some, the Unconquerable sun; others, Mithras.

Toward the end of the century, the successful soldier-emperor Diocletian tried to stabilize Roman society. To solve the problem of political power, he devised a cumbersome system of joint emperors, the junior succeeding the senior, at regular intervals. To solve the economic problem, he tried to freeze all prices; predictably, it did not work. Neither did his arrangements for the succession to power; emperors would not retire at the appointed time, though Diocletian himself did — and rivals turned their armies against one another. Soon there were six or seven self-proclaimed emperors ruling in different provinces and all seemed set for a return to the chaos of the preceding century.

One of these contenders for power, Constantius Chlorus, ruled in Britain and Gaul. He died in July, 306, in the legionary camp at York. His eldest son, Constantine, had the support of the army and came to terms with Severus, who ruled in Italy and Africa. Their plan to rule as joint emperors in the West was short-lived: in a few months, Severus was eliminated by Maxentius, son of Diocletian’s old colleague Maximian. Constantine felt his position threatened and in any case, he would never have been content to share power. In 307 he proclaimed himself sole legitimate Emperor in the West.

At first, Constantine had to ward-off German attacks on the Rhine frontier. After a year or two of marches, battles, sieges and skirmishes, he could be sure of his rear regions. In 310 he advanced into Spain, defeated Maxentius’ forces there and gained control of the provinces, but this was not enough. The key to lasting and stable power, lay in Italy and above all in Rome. Constantine’s army was by now a disciplined and confident force, accustomed to victory. In 312 its commander decided to put its fortune and his own — to the ultimate test by invading Italy.

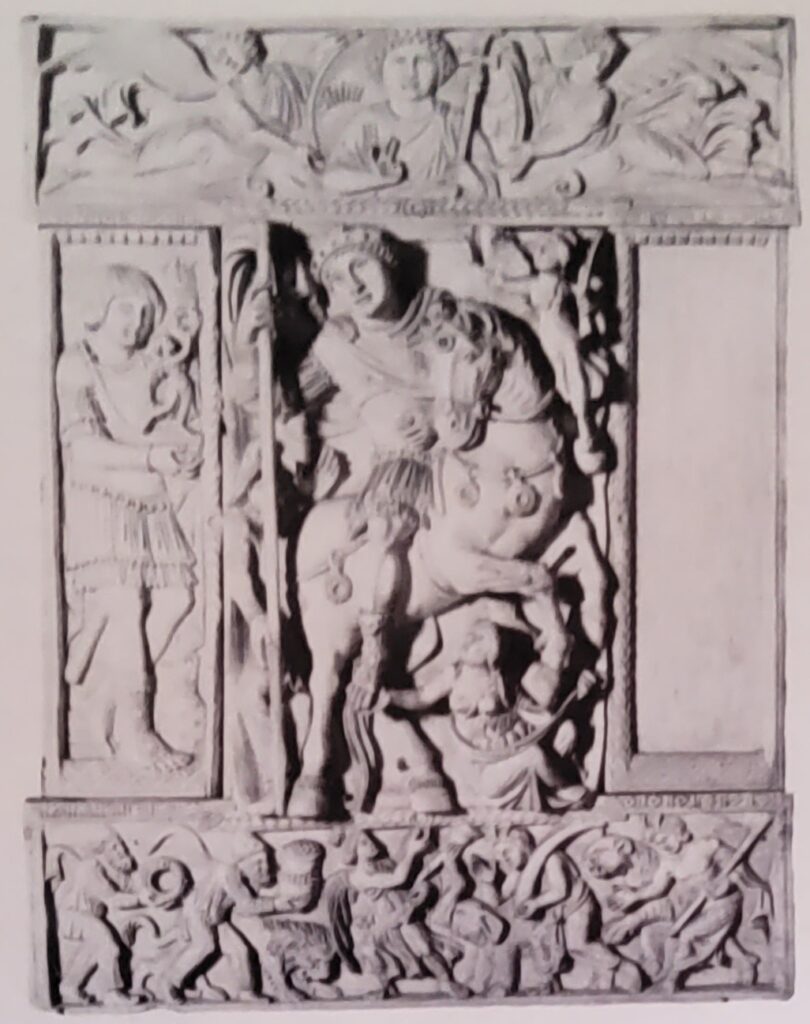

In This Sign Shalt Thou Conquer, Constantine marches on Rome

In the late summer of 312, Constantine marched his army across the Alps. It was not a large force, for he could not risk denuding the Rhine frontier of troops. Although Maxentius’ army was many times larger, he was no soldier. He waited irresolutely in Rome, plying the pagan gods with sacrifices and magic rites. Constantine, as always, was decisive, rapid and driven by an overmastering lust for power. Susa, at the exit from the Alpine pass, was taken by storm. Turin was entered after a cavalry battle. Without resting, Constantine pressed on to Milan. A few days to rest his tired but exultant troops and he advanced on the strongly fortified city of Verona, which controlled the crossing of the Adige. Before the city wall stood the main force of Maxentius’ army, in northern Italy. The battle was long and hard-fought, but discipline and leadership told. By evening, the plain was strewn with corpses and Constantine held Verona.

The conqueror was now free to march on Rome, His route, through Bologna, across the Apennines to Florence and southward through Etruria, was that followed today, by the Autostrada del Sole. During his march south, he had a portentous vision.

This was not Constantine’s first vision, A few years earlier, in Gaul, Apollo the sun-god had appeared to him. More than most men of his age, Constantine was alert for the miraculous. Years later, he recounted to Eusebius, the Bishop of Caesarea, what he had seen on the road to Rome, that autumn day in 312. Eusebius recorded the story:

“He called to God with earnest prayer and supplication that he would reveal to him who he was, and stretch forth his right hand to help him in his present dangers. And while he was thus praying, a most marvelous sign appeared to him from heaven, He said that about noon, he saw with his own eyes, a cross of light in the heavens, above the sun, and bearing the inscription BY THIS SIGN SHALT THOU CONQUER. At this divine sign he was struck by amazement, as was his whole army, which also witnessed the miracle.”

The nature of Constantine’s vision has been discussed for centuries. The most plausible explanation is that he saw a solar halo, which is sometimes cruciform. The inscription, was probably the product of his own, overheated imagination. Be that as it may, Constantine believed that the god of the Christians, had revealed himself as the true god and had promised him victory.

As he slept in his tent that night, he dreamed that Christ appeared to him, displaying the same sign and commanding him to make a likeness of it and use it as his standard in battle. At dawn the next morning, he set his artificers to work to fashion the labarum, a Christian version of the traditional Roman military standard, with the monogram of Christ set in a wreath surmounting it. It was an overt proclamation, that Emperor and army, were under the protection of the Christian god. Sure of his destiny, Constantine pressed on to Rome.

As his enemy approached, Maxentius at last bestirred himself. His forces outnumbered Constantine’s, but army and populace alike, were demoralized by famine and by the capricious barbarity of Maxentius’ rule. Finally, Maxentius was a poor strategist. Encouraged by an ambiguous oracle, which told him that the enemy of the Romans would perish, he stationed his army by the Milvian Bridge, where the Via Flaminia crosses the Tiber, about two miles from the walls of Rome. The army thus had its back to the river, always an uncomfortable situation. To make supply and reinforcement easier, he constructed a second bridge of pontoons or boats, close by the existing stone bridge.

On October 26, 312, Constantine reached his enemies position. At once he began attack and Maxentius’ ill-prepare and unenthusiastic forces soon cracked. Constantine threw his reserves into the breach and all along the line, Maxentius’ men, afraid of being surrounded, turned tail and ran. The rout was complete. Emperor and army fled back to the river, hoping to reach the far bank and the safety of the walls. As Maxentius was crossing the bridge of boats, it collapsed. Rumour at the time, said that as a trap for Constantine, it had been built to break, but this seems like an explanation after the event. The fleeing soldiers panicked and in the crush, Maxentius was thrown into the river. The next day his body was found and its head was cut off and carried on the point of a spear into Rome.

There was no further resistance to Constantine. Crossing the Milvian Bridge, he entered the city the next day by the Porta Flaminia, amidst the acclamations of Senate and people. He had united the whole western half of the Roman Empire under his own rule.

Equally important, Constantine felt that the god of the Christians had demonstrated his power by granting him the promised victory. Henceforth, he was committed to the support of the Christian Church. That Church – from being a repressed, poor and occasionally persecuted minority of low social status – now found itself suddenly, raised to the heights of power, prestige and patronage.

After a brief stay in Rome, Constantine returned to Milan. There he had a meeting with Licinius, who held the Balkan provinces. It was in their interest to make common cause against Maximinus, the ruler of Asia Minor and the East. Their alliance was sealed by the marriage of Licinius to Constantia, the sister of Constantine. At the same time, the two emperors issued a joint edict on religious toleration, the famous Edict of Milan:

“We resolve to grant both to the Christians and to all men freedom to follow the religion which they choose, that whatever heavenly divinity exists may be propitious to us and to all who live under our government.”

Further clauses spell out the details of the program of toleration and ordered, the restoration of Christian places of worship that had been confiscated.

The Edict of Milan marked the triumph of Christianity over persecution and put it on the same footing as other legitimate religions. It did not establish the Church as the official religion of Rome, but it was accompanied or followed in the next few years by a series of enactments favouring the Christians. Members of the clergy were exempted from costly municipal duties — and the wealthier classes, upon whom these duties fell, now began to become priests and bishops. Regular payments were made to churches from state funds. Sunday was proclaimed a holiday in the army: for some, it was the feast of Christ, for others that of the sun god. The churches were recognized as legal institutions, able to receive legacies and administer property. The decisions of bishops were given the same validity in civil law as those of the courts. Freedom of pagan sacrifice was limited by legislation; some pagan temples were closed and their property sequestered.

Constantine and members of his family gave lavishly for the building of churches all over the Empire. When the Church itself split into factions – either because of the conduct of individuals during persecutions, as in Africa, or because of doctrinal disagreement – Constantine intervened. He organized synods and councils, and put strong pressure on them to reach an agreement. As a last resort, he used the arm of the civil power to enforce the decisions of the Church.

Although Constantine never wavered in his espousal of the Christian cause, he was not baptized until 337, when he was on his deathbed. Such deathbed baptism was common at the time: by making it difficult to commit a mortal sin between baptism and death, salvation was guaranteed.

Constantine, who held absolute power in a violent age, had sinned much; his hands were stained with blood, not least with that of his son Crispus, accused by the Empress Fausta of an attack on her virtue. Fausta herself was the next victim, charged with false accusation, and while the true facts of the case are lost, the executions in both cases were by Constantine’s order. His approach to Chriistianity was gradual and idiosyncratic. In 312 he probably knew little theology and less about the history and organization of the Church. Years later—we do not know exactly when—he was able to preach an Easter sermon, in which he touched on many of the thorniest problems of Christian doctrine. He was fond of referring to himself as the bishop of those outside the Church. What he presumably meant was that, by guiding the Roman state along Christian lines he ensured divine favour and protection for the Romans as a whole, including those who did not accept Christianity.

Constantine’s conversion to Christianity

Constantine’s conversion has fascinated historians and psychologists for centuries. Yet, all is still not clear. The difficulty is two-fold. First, the world of ideas of the early fourth century is strange to us and many of the key facts are unknown. Second, there is the problem of entering into the mind of this unusual man—unusual to his contemporaries as well as to us. Ill-educated, but fond of the company of scholars; gentle and humane, yet never hesitating before a battle—or an assassination; superstitious and otherworldly, yet a realistic administrator and a bold and decisive reformer. Constantine was a man of many parts.

Today we know more about the fourth century than scholars did a generation or so ago. It may be, that we have a deeper understanding of psychology in general and religious psychology in particular, than they had.

One long-held view can be rejected out of hand. According to this theory, Constantine’s conversion was entirely a matter of policy, carefully and cynically calculated. Designed to win for him the support of a numerous and important group in the society of the time, but the Christians were neither numerous nor important, this was especially true in the western half of the Empire.

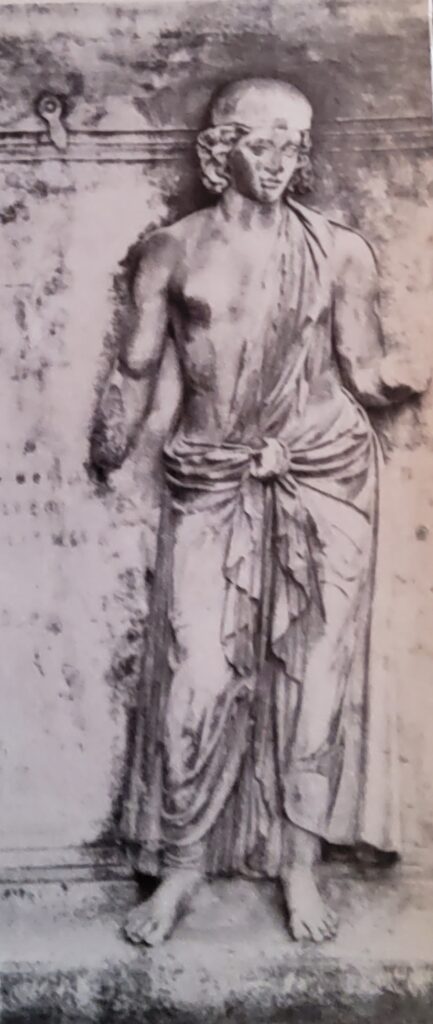

It is true that Christians were more numerous in some of the eastern provinces, but in 312, the eastern provinces were not Constantine’s problem. Even there, Christians were far from forming a majority. It is unlikely that Christians, however we define them, formed ten per cent of the population of the Empire. As for their importance, there were upper class Christians, of course; but the bulk of the Christian community seems to have belonged to what we call the lower middle class of the cities and towns — traders, artisans, small landowners and petty “rentiers,” whose influence on the course of affairs was negligible. Nowhere were the country people Christian. The army, whose support was crucial for Constantine until the last of his rivals had been eliminated, was and long remained solidly pagan. If Constantine’s conversion was a matter of calculation, it was an ill-considered one, and with no real bearing on his success.

Constantine was evidently a religious man—in the terms of the early fourth century—in that he was anxious to identify the Supreme Power that ruled the universe and to put himself in the right relation with it. He was also an ambitious man, one determined to concentrate the imperial power in his own person and then pass it on to his sons. He did not seek the personal indulgence that power permits. He was no Maxentius, unable to see beyond extortion and debauchery. He was, in fact, rather austere in his personal life. For him, power meant the ability to impose order upon chaos, to tidy up the appalling mess of the Roman Empire. He wanted to find God, but not in any spirit of humility; he was a man fully conscious of his mission and of his ability to accomplish it, if only the power that ruled the universe would help him.

The war with Maxentius had been a desperate gamble. As Constantine marched through Etruria to the decisive conflict at the Milvian Bridge, he must have anxiously hoped and prayed for a revelation. In these circumstances it is not surprising that one was vouchsafed him. He had Christians in his entourage, among them his mother Helen, who was later canonized as a saint. Repudiated by his father for the sake of a dynastic marriage, she was a devout Christian, who in her old age made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land and there, it is believed, found the True Cross. The god of the Christians, was to Constantine, one of the candidates for Supreme Power in the universe. In a state of emotional exaltation, he took a natural phenomenon for a divine sign. That his revelation was corroborated by a dream that night, also need surprise no one. What confirmed Constantine in his assurance — not only that the Christian god was the true god, but that he, Constantine was his chosen vessel — was the victory a few days later at the Milvian Bridge, a victory that changed the shape of the world.

Constantine lived and reigned for twenty-five years after 312. In 324 he invaded Licinius’ territory, confident that he had the protection and support of the Almighty. A naval battle in the Bosphorus and a land battle at Chrysopolis on the Asiatic shore sealed Licinius’ fate. Once again, the god of the Christians had given victory to his servant, Constantine now held the whole of reunited Empire.

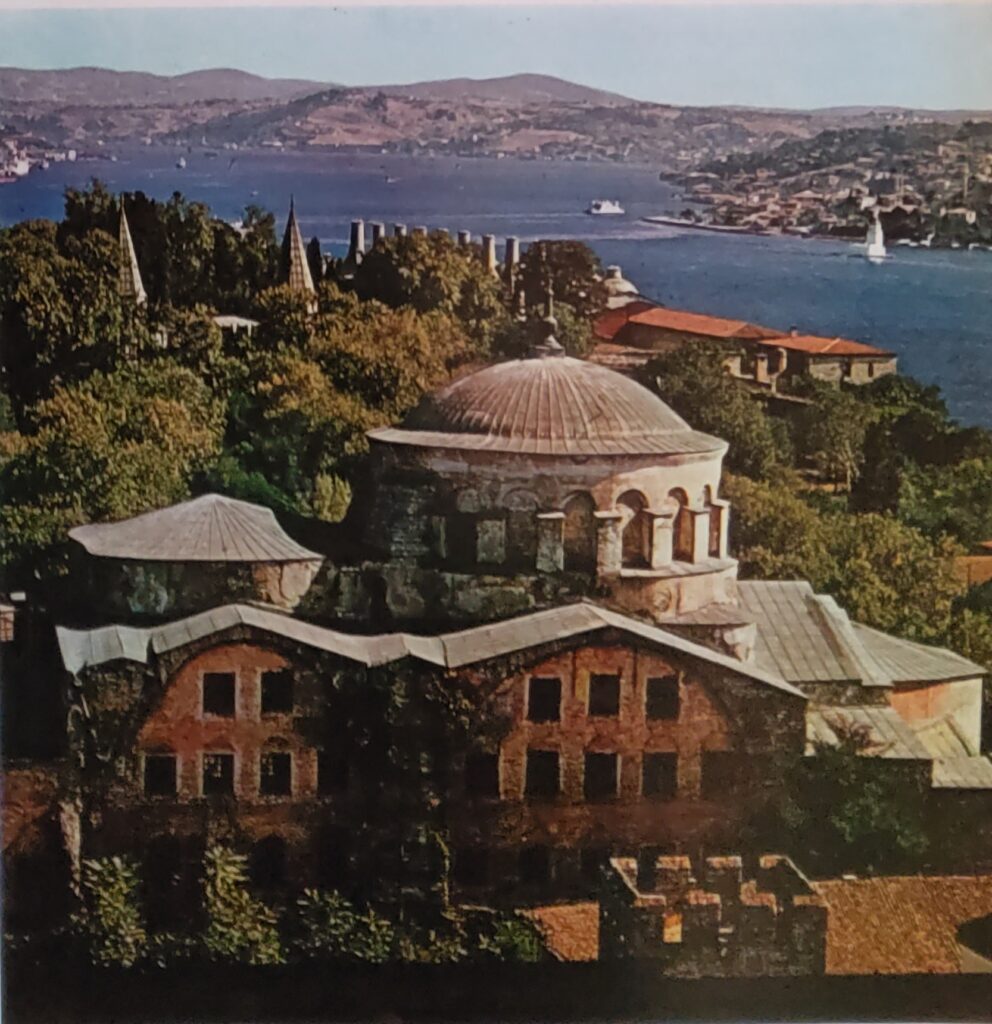

It was then that Constantine refounded the ancient Greek city of Byzantium, calling it the city of Constantine – Constantinopolis — and designating it the second capital of the Empire, the new Rome. No doubt Constantinople lay on one of the main military roads of the Empire, leading from the Rhine and Danube frontiers to the Persian frontier. No doubt, too, that the economic and demographic centre of the Empire lay in its eastern provinces. Yet it was not these considerations that led Constantine to found the new capital and to enrich it with the spoils of the Empire. He said himself, that he gave the city its name by the command of God. It was to be the first wholly Christian city in the world. Adorned with magnificent churches built on the Emperor’s command and containing no pagan temple. Constantine surely intended it as a symbol and a memorial of his final victory—won close by—and of the accomplishment of his great design.

Meanwhile, faced in the East with a split in the Church on doctrinal matters, Constantine had once again intervened. The Council of Nicaea in 325, at which the Emperor himself presided, defined the beliefs of the Church. The Emperor ordered that they be adhered to and put the full weight of the State behind the Church authorities in dealing with recalcitrants. To Constantine, it seemed his obvious duty, to ensure that worship was conducted in a manner pleasing to the Almighty. Thus, though the majority of Romans were still pagans, though Constantine himself still retained the old pagan office of pontifex maximus, though pagan symbols still appeared on the coinage, a further step was taken towards the fusion of the Roman State and the Christian Church.

With the vast mass of bullion that his victories had given him, Constantine issued a new gold coin of guaranteed purity, the solidus. This, together with the peace of a united Empire, ended the inflation and encouraged trade and industry.

The administration of the Empire was radically reorganized. Civil and military power were rigidly separated; a mobile strategic reserve was created; and a new hierarchy of officers of state, responsible to the Emperor himself, was established.

Constantine had his sons, Constans and Constantius, brought up as Christians; unfortunately became religious bigots. Later they were appointed junior co-emperors and arrangements were made for them to succceed their father on his death. All did not go exactly according to Constantine’s plan, but a major struggle for power was avoided. Until 350 Constans ruled in the West and Constantius in the East. From 350 until his death in 361 Constantius reigned as sole Emperor, like his father before him.

As Constantine, at last baptized and a full member of the Christian Church, lay on his deathbed on Whitsunday of 337, he could reflect that he had solved the constitutional, military and economic problems of the Empire and that he had given it a new capital and a new religion.

Alaric the Goth sacks Rome in 410

We might put the emphasis differently today. The Roman Empire Constantine knew soon crumbled. In 410 Alaric the Goth sacked Rome. Soon the western provinces and even Italy itself, became barbarian kingdoms. The eastern provinces, Greek in speech and Greco-Oriental in thought and feeling, survived. With its capital, Constantinople, the Eastern Roman Empire for a thousand years, preserved the cultural heritage of Greece and the political heritage of Rome.

Constantine’s other innovation is still with us,and without it, European civilization would be unrecognizable. It was Constantine who launched Christianity on the path to power. In the half-century between the battle at the Milvian Bridge and the death of Constantius, the Christian Church changed decisively. From being a persecuted, inward-looking minority, it became a confident, sometimes arrogant majority. Not only were Christians far more numerous in 361 than in 312, but they now counted their adherents among the influential upper classes; they had taken over and adapted the intellectual heritage of Greece and Rome; their churches were the most magnificent buildings in the cities and their bishops were the leading citizens. The Church had acquired prestige, riches, power and a network of communications extending to every village of the Empire. Julian the Apostate’s attempt in 361-63 to put back the clock failed.

There was nothing inevitable about this. Christianity had a missionary dynamic, but so had other religions. Without the support of a successful ruler, it could not have become the commanding ideology of the Empire. We need only glance at Rome’s neighbour Persia, to be convinced. There Christians were an active, occasionally persecuted minority and they remained this way until they were overwhelmed by the Arab conquest. No Emperor ever paid much attention to them, let alone gave them his passionate and powerful support.

As we survey the history of the Middle Ages, the Renaissance and modern times, almost everything that we see — from the great cathedrals of Europe, the iconography of our art, and the imagery of our literature, to our systems of education, law and philosophy, owes much of its shape to Constantine’s vision on the road to Rome and his victory at the Milvian Bridge.