In the spring of 432, Laoghaire, ruler of a petty kingdom in northern Ireland, gathered his court near Tara to celebrate the annual rites of his pagan religion. The Christian missionary Patrick, appeared in the midst of the gathering, confounded the King’s magicians with a miracle of fire and — on Easter Sunday — converted Laoghaire. Patrick went on to strengthen the fledgling Christian Church in the Emerald Isle and to establish a religious tradition that was to endure for centuries. As Continental Europe slipped into the Dark Ages, following the collapse of the Roman Empire, it was the monks of Ireland who kept alive the flame of faith and who as missionaries — brought that faith back to the lands where it had been lost.

According to the annals of Ireland, St. Patrick arrived there in 432 and died three decades later, in 461. His mission to Ireland had been prompted by a series of dreams or visions, which strengthened an earlier resolve to dedicate himself to God’s service. His great work, the Confessio (written about 450), is his spiritual autobiography, his account of his dependence upon God for his ability to carry out this resolve. We gather from Patrick’s own words that the journey of 432 was made with a set purpose, the evangelization of Ireland. He recognized to the full, his natural disabilities, such as teaching and writing in a tongue not his own, but outweighing all these, was his unshakable belief that God had dedicated him to be a bishop to the Irish.

When St. Patrick went to Ireland he knew very well, what kind of country he was going to. Years before, when he was only sixteen, he had been carried off, from his father’s home in Bannavem (either in Britain or Gaul) by pirates and taken to Ireland. There he was bound to a master, Miliucc, whose flocks he tended for six years. Then in response to a dream, he traveled two hundred miles to the coast and escaped by ship. He eventually reached his own family, but soon, in another dream, a man named Victoricus appeared to him with letters, from the Irish, begging him to return to them. Accordingly he set out once more for Ireland.

Patrick appears to have landed on the east coast, but we must leave the saint’s own narrative at this point, for he tells us little about his practical life and his work, though we learn something of the insults that he had to endure from unbelievers, something of his converts and of the sons and daughters of Irish chieftains who, at his urging, became monks and virgins of Christ. Otherwise, he speaks merely of journeying through many perils, even to outlying regions beyond which no man dwelt; and where no one had come to baptize, or ordain clergy, or confirm the people. The Confessio concludes with a pious hope that on this account, he should never part with his people and a prayer for perseverance in whatever he should have to endure.

The rest of our information comes from Muirchu, a seventh-century chronicler. Patrick resolved, as his first act, to go to his former master Miliucc, with an offer to pay him the ransom, that would have been due to him, if Patrick had not escaped; and also with the hope of converting him. Muliucc, however, heard of his coming and the chronicle says, set fire to himself, his house and all within it.

As the Feast of Easter was now approaching, Patrick proceeded on foot to the Plain of Tara, where King Laoghaire and his court were celebrating the great heathen feast of the druids. On his arrival Patrick kindled a fire by miraculous means, confounding Laoghaire’s magicians and throwing doubt on their ancient traditions. The king marched out from Tara and summoned Patrick to appear before him, but Patrick, according to the legends, brought a great darkness over the land and the frightened king feigned conversion and returned to Tara. The next day, Easter Sunday, Patrick entered the hall of the king’s palace to preach the Gospel and emerged victorious from all contests with the druids. Patrick then threatened the king with death unless he truly believed. On the king’s compliance, Patrick granted him his life, but because of his obduracy, he prophesied that none of his seed should be king thereafter.

It is clear that the Easter ceremony is the climax of Muirchu’s traditional narrative. The conversion of the king of Tara was, in his view, the apotheosis of Patrick’s evangelization of Ireland. Along with it, he laid great emphasis on the keeping of Easter and on the transition from the heathen to the Christian ceremony. The conversion of Ireland and the adoption of the “Patrician,” or Roman, Easter are evidently held to be one and the same thing.The Tara episode is followed in Muirchu’s chronicle by a series of miracles much more briefly told, including the story of the bestowal of the land of Armagh on the saint and ending with the story of the choosing of the little boy Benignus as Patrick’s successor. Most of Book of the chronicle, is devoted to accounts of the saint’s death, tidings of which he was said to have received from an angel and which he sent to Armagh, ‘‘which he loved beyond all other places,” summoning men from there to assist him to his last resting place. Patrick is believed to have died in 461 and to be buried at Saul, near the present city of Armagh.

Muirchu’s Life is a chronicle in the form of a biography, but a comparison with Patrick’s own Confessio reveals at once, the tendentious nature of the former document and above all, the change in the gentle and noble picture of Patrick himself, to a wonder worker who indulged freely in curses and vengeance.

Muirchu’s information about Ireland at that time concentrates on the “high-kingship”’ because, at the time he was writing, Tara was the political centre of Ireland. King Laoghaire was the eldest son of Niall Noigiallach, who had made himself master of the north of Ireland by conquering the ancient kingdom of Ulad, which had formerly stretched across northern Ireland from Antrim to Donegal.

In Patrick’s time, Ireland was divided into a number of coiced or small kingdoms and there was no “high-king.” Niall is believed to have conquered the Ulad and destroyed their capital, Emain Macha, which was only two miles from Armagh. He presumably made Patrick his chaplain there, but one can only speculate on the sequence of events that led to this, since he could hardly have liked or trusted Patrick. Niall had raided often in late Roman Britain and his mother’s name was Cairinn (from the Roman, Carina). Late Roman political influence may have helped place Niall in his advantageous position in central Ireland and may also have influenced the appointment of Patrick.

With Niall we enter a new phase of Irish history, just as with Patrick we enter a new phase of Irish religion. The two came about simultaneously. Niall must have been a very able politician to create and retain his central position; and to retain, in that age, the loyalty of his sons. His influence grew and by degrees he acquired the midlands. His policy can be traced in the work of Muirchu and in that of another chronicler, Tirechan of Armagh. Undcr Niall the influence of Patrick’s work also grew.

Patrick was not the first to introduce Christianity into Ireland. According to Prosper of Aquitaine, a fifth-century theologian, Palladius was sent to the Irish as their first bishop by Pope Celestine in 431. Little is known of Palladius, but he probably worked in Wicklow in the south of Ireland. Muirchu tells us that his efforts met with little success, that he eventually left and dieed in the land of the Picts (Scotland).

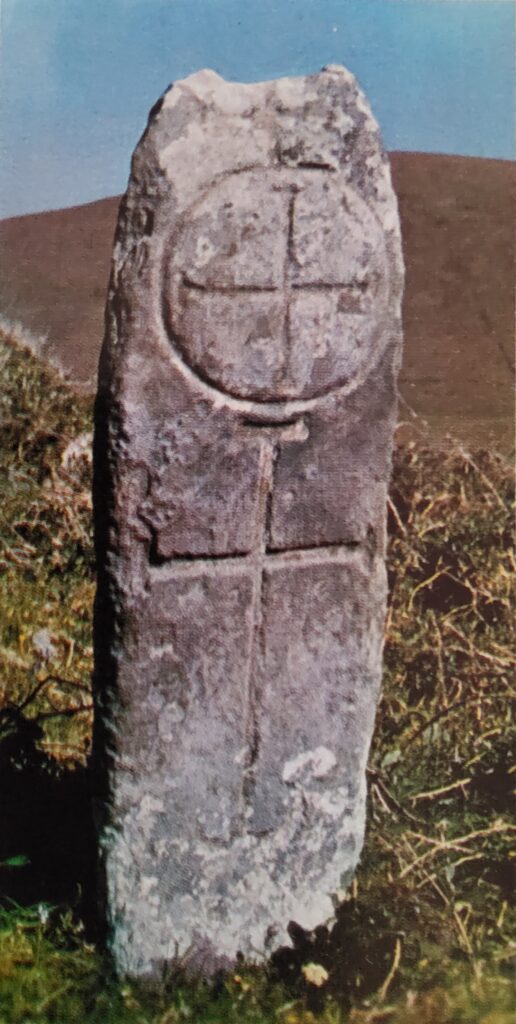

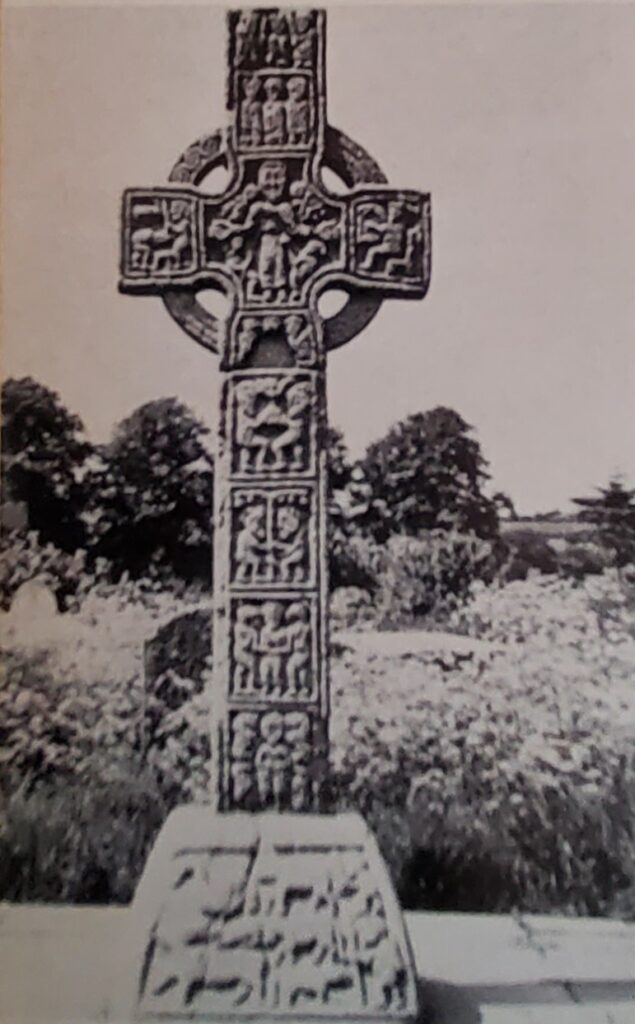

The centralization of episcopal authority in the see of Armagh is one of the first signs of Patrick’s Roman influence. In Gaul the bishops were centered in the principal towns of the provinces, but in Ireland, where Roman influence was less direct and up-to-date, the bishops were stationed in the monastic centres, the only places of civil organization. For the same reason, the earliest Iearning of the Irish was centered in the monasteries and it was the monasteries that acted as the distributors of learning, to the surrounding districts.

The change came about very gradually. Ireland had always been an agricultural country, lacking the towns that Gaul possessed and which constituted the framework of her ecclesiastical orranization. Ireland had substituted for them monastic foundations with an agricultural economy, where the bishops held a subordinate civil position, the abbots holding the political power. Above all there was no unity such as had been established in Gaul by the Roman political regime. Each monastery was independent of its fellows and differed in its masses and daily routines.

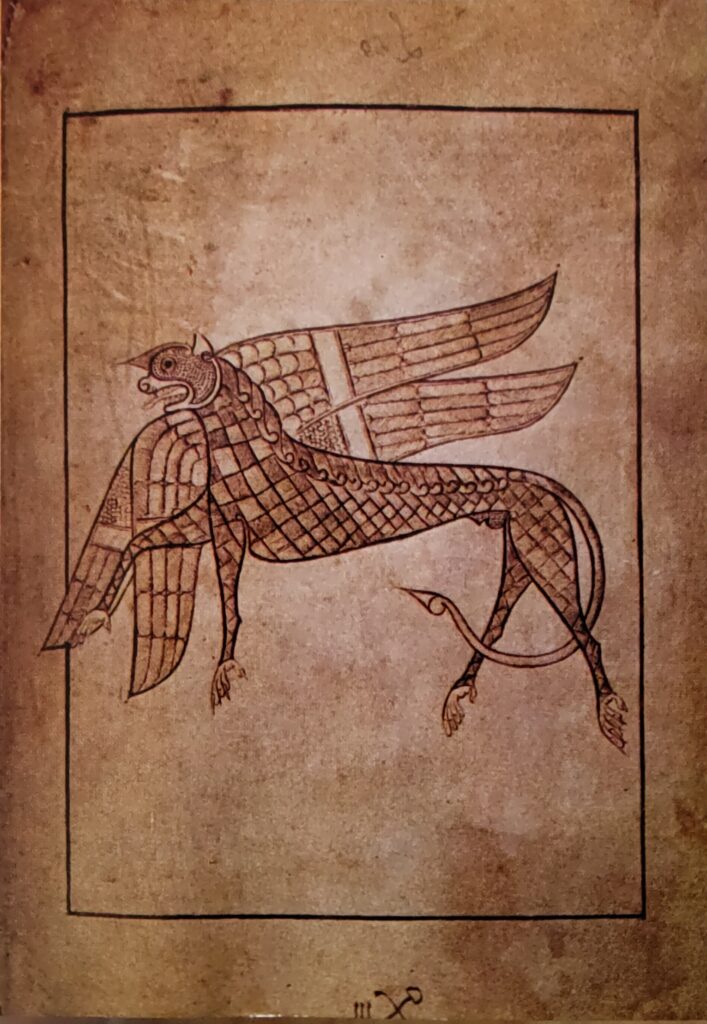

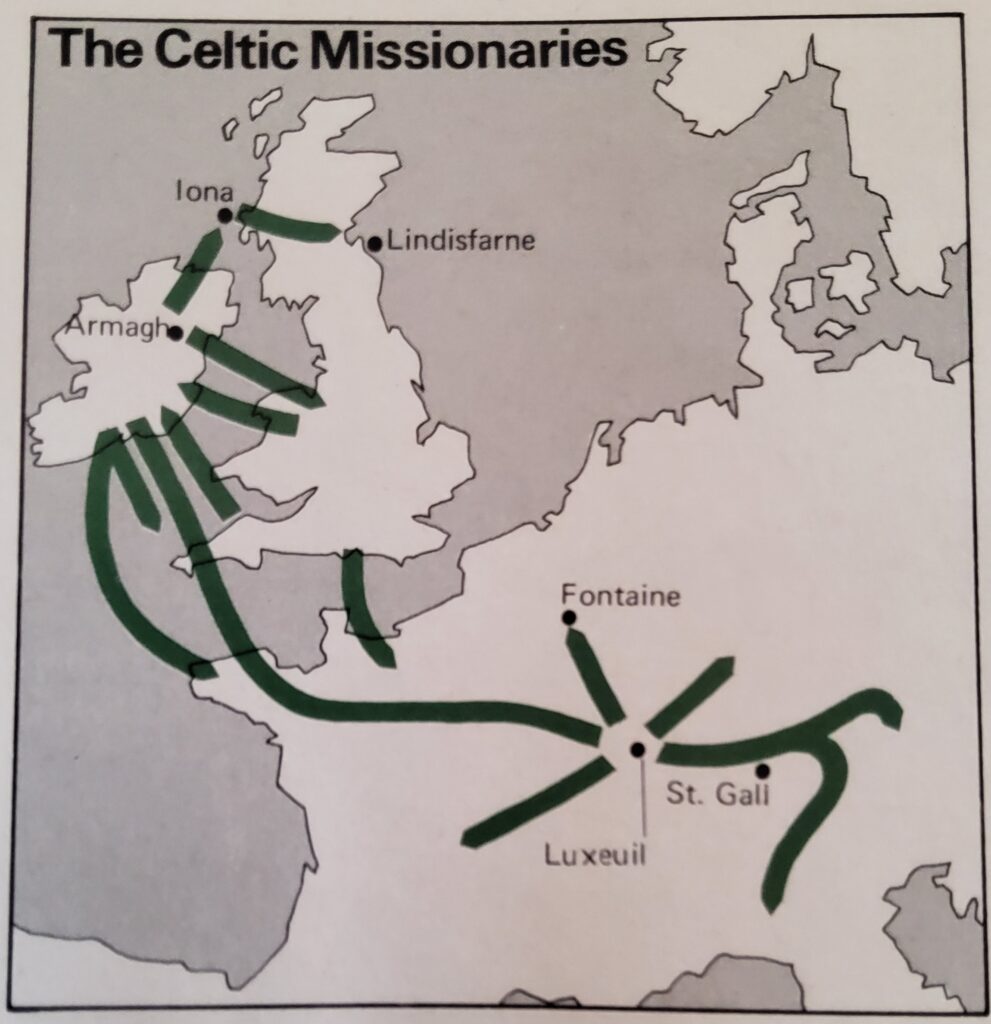

The Irish habit of wandering was the beginning of the most remarkable missionary work of the early Church, to which Christian Europe owes much. About the year 585, we find St. Columbanus setting out with his twelve companions on his celebrated journey to Gaul and beyond. At the beginning of the Carolingian Age the Irish monk Dicuil, tells of Irish papas, “clergy,” who had been found in Iceland and in the Faroes, shortly before his own day. We find Dicuil himself at the court of Charlemagne and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that three Irish monks had sailed to Britain in a coracle, without sail or rudder and with only a limited supply of food, because they wished to be on pilgrimage “they recked not whither.” This follows an ancient tradition, in line with the casting adrift of Maccuil by Patrick, in chapter 23 of Muirchu’s Life.

The Death of St. Patrick

The death of St. Patrick did not mean the end of his see at Armagh. We can see how firmly rooted this was by the fact that it survived till modern times without any obvious diminution of its prestige. About this time, the latter half of the fifth century, the breakdown of Roman authority in Britain was complete and with the disintegration, there was a consequent slowing down of communications between the two countries. Britain closed in upon herself. Ireland was left virtually alone and continued to develop on her own lines.

These lines were now twofold, however. There was first, the older monastic regime in which each monastery was governed by the abbot, and where the bishop lived in the monastery in a purely spiritual office; and there was the newer regime, according to the Catholic Order from Armagh. This second order was under the Meath Dynasty and was gradually changing, while the monastic naturally lasted longer, being more widespread and deeply rooted. The result was a struggle between the two Churches, especially in the North. The gradual change that came about can best be seen in the history of St. Columba of Iona.

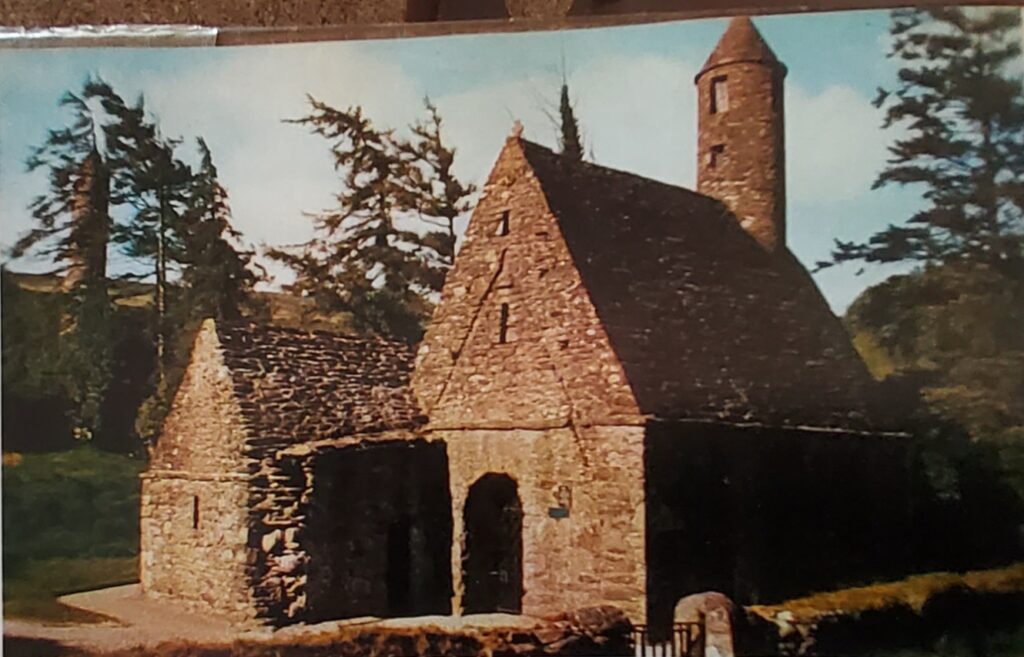

Born in Donegal about 520, Columba is said to have been trained for the Church from an early age. He left Ireland about the year 563, at the age of forty-three and led a migration of some twelve followers, from the country of Dalriada in the north of Antrim to Argyll in Scotland. He settled on the island of Iona, southwest of Mull. His biographer, Adamnan, gives no reason for the move save that he wished to be a pilgrim for Christ – the old habit of wandering.

Some twenty years later another famous saint, Columbanus, was trained at the monastery of Bangor in County Down. At the age of about forty-five, he obtained leave from his abbot to go to the Continent with twelve companions, including St. Gall. Here he proved himself one of the most influential of the Irish monks. He founded three important monasteries in the Vosges Mountains, first in Annegray, next in the chief monastery in the great Luxeuil and finally, in nearby Fontaine. Columbanus’ inflexible adherence to the older system of Irish ecclesiastical government and his political views gave offense to the bishops and to Queen Brunhild; and he and his Irish monks were ordered home to Ireland in 610. He was able to escape at the moment of embarking and eventually reached Bregenz on Lake Constance.

From Bregenz, leaving St. Gall behind him in the great monastery that still bears his name, he made his way over the Alps to Bobbio in Italy. He was given land on which to build his famous monastery, which he began in 614. He died there in the following year at the age of about seventy-five. His exacting rule was undoubtedly that which he had adopted from his Irish monastery at Bangor. In spite of its severity, his own activities and those of his disciples gave it a wide diffusion in France, Germany and were of enough importance for Pope Gregory II in 719 to commission St. Boniface, to counteract the Irish influence in Germany. St. Clothair and later kings in Gaul protected and endowed Luxeuil.

Meanwhile, the influence of St. Columba’s sanctuary on Iona gradually spread. By a curious coincidence, about the time of St. Columba’s death, Pope Gregory I, sent a mission to Kent under St. Augustine in which the Roman Order was naturally inculcated. Bede tells us that St. Augustine first preached to the King, Aethelbert, who had in fact already heard something of Christianity. His queen was Bertha, of the Christian royal family of the Franks. The King was converted and baptized in 597. He gave Augustine and his companions residence in his royal city of Canterbury. The next king of England to receive baptism was King Edwin of Northumbria, in 627; and his conversion came about chiefly through his marriage to the Christian princess Ethelberga, daughter of King Aethelbert of Kent. With her to Northumbria went her chaplain Paulinus, through whose zeal and by whose guidance Edwin’s subjects soon followed the example of their King and were converted to the Catholic faith.

After the death of King Edwin, his immediate successors lost the faith, but it was restored with the accession of Oswald, who had spent his early life on Iona and been trained in the Celtic Order. It was during the reign of Oswald’s brother and successor, Oswiu, that the controversy over when the feast of Easter should be celebrated reached its height. At the Synod of Whitby, held in 664, the cause of the Roman Church, quoting the authority of St. Peter and the decision of the Council of Nicaca, was upheld by Bishop Wilfrid of Ripon; and that of the Celtic Church, which preferred the older practice of rechoning Easter in the same way as the Jewish Passover, by Colman, Bishop of Lindisfarne. Oswiu and his people decided in favour of Wilfrid and Rome. In 669 Theodore of Tarsus, consecrated Archbishop of Canterbury by Pope Vitalian, arrived in England. During his archiepiscopate the unity and organization of the Church of Canterbury was secured.

Iona sacked by the Norsemen

The death of St. Columba did not at all mean that the sanctuary of Iona came to an end. On the contrary it continued to flourish under a succession of Columba’s collateral descendants for several centuries, till the time of Adamnan; but the gradual extinction came with the repeated incursions of the heathen Norsemen, who sacked it time after time. In 802 the monastery was burned and in 806 some sixty-eight monks were slain. In 825 the whole community perished. At last in 849 the sacred relics were transported to the new church at Dunkeld by Kenneth MacAlpin.

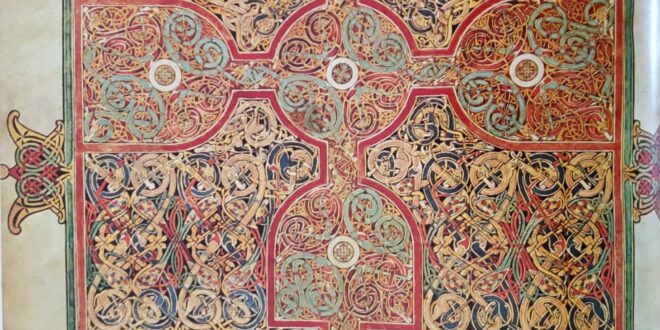

Iona was not the only sanctuary destroyed by the Norsemen. In Ireland, especially, the destruction was great and traces of heathenism did not finally disappear in Ireland until the end of the ninth century. Monasteries such as Clonmacnois, which had been founded in 548 and which had been virtually a university, were pillaged of their treasures. There was a wholesale evacuation of monks to the Continent, some carrying their books with them but far more carrying with them, as more easily portable, the Latin learning that, especially since St. Patrick’s day, they had been quietly absorbing in their monastic libraries. In this matter, Ireland’s loss was a gain for Europe. Many a Continental library has been enriched by manuscripts salvaged from the Viking period in Ireland and by the learning of her refugee monks.

Among the most famous of the scholars who left Ireland for the Continent at this time, were Sedulius Scottus and Johannes Scottus. Sedulius was a member of the court of King Charles the Bald at Liège and may have been a member of a mission of Irishmen, that is known to have come in the middle of the ninth century, to the court of Charles the Bald from Maelsechlainn, the Irish king. He was one of the most learned men of his time – poet, scholar, scribe, theologian and courtier. He was a precise Latin scholar and there are hints of Irish sources in some of his writings and some slight knowledge of Greek.

Even more remarkable was Johannes Scottus Eriugena, “John the Irishman”. Little is known of his origin or of his early life, but he was also a member of the palace school of Charles the Bald. He must have arrived there at least as early as 845 and remained at least till after 870, probably as a teacher. His learning was wide and precise, including Latin and Greek, the latter a rare accomplishment of his day. Among his many writings, the greatest is the De Divisione Naturae.

It is impossible for the Classical scholar to exaggerate the significance of the part played by the Irish in the work of preserving Classical literature. From the earliest period one has only to think of St. Gall and Bobbio; and during the ninth and tenth centuries there had been hundreds of refugee monks, who sought the retreats offered by the Irish monasteries of Péronne, Laon, Reims, Fulda, and Würzburg. In the eleventh century Ratisbon was founded by an Irish monk from Donegal, on his way to Rome. From Ratisbon foundations were made at Würzburg and Nürnberg and even at distant Kiev, a monastery was founded which lasted till the Mongol invasion in 1241. For three hundred years, these abbeys kept in touch with Ireland and drew their monks from them.