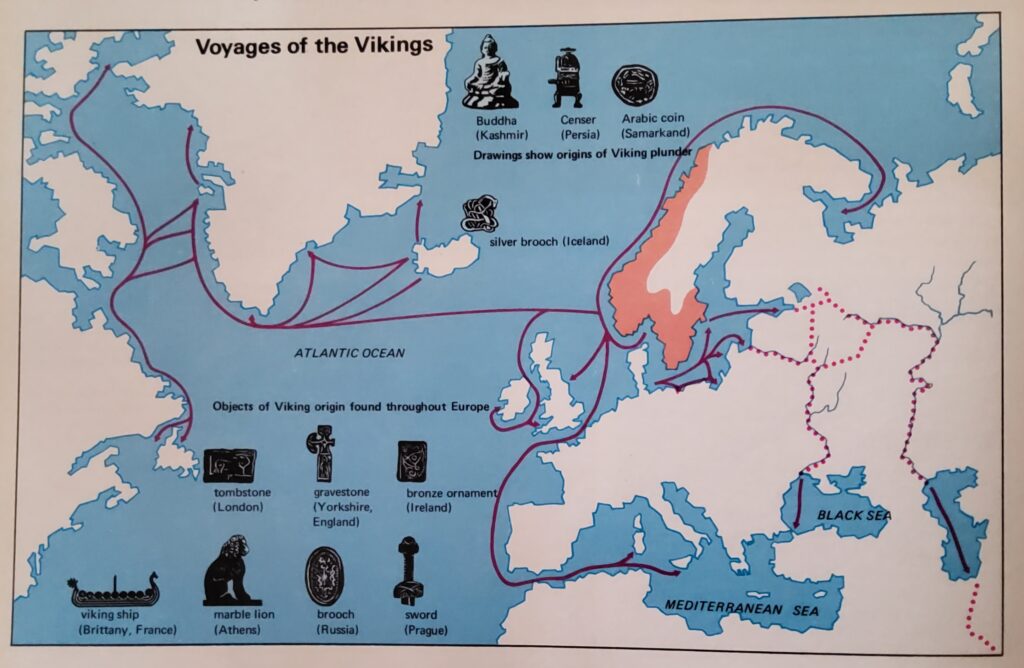

Norsemen or Vikings – Danes, Norwegians and Swedes — were terrorizing the greater part of Europe, over a thousand years ago. Their earliest activities were chiefly limited to raiding and destroying; occupations for which their mastery of the sea admirably suited them. In time, they came to settle down — in the British Isles, in Iceland and in Greenland. It was this last, snow-covered and icebound land that was first colonized by Eric the Red — a man so named because of the colour of his hair, his fiery temper and murderous blood on his hands. Eric’s son Leif, introduced Christianity to Greenland and in a voyage even farther west, came upon a land, rich in grapes, that he named Vinland the Good. The Vikings did not stay long in Vinland and the colony in Greenland eventually expired. Five hundred years later, another voyager west, Christopher Columbus, rediscovered the “lost continent” and the world called it America.

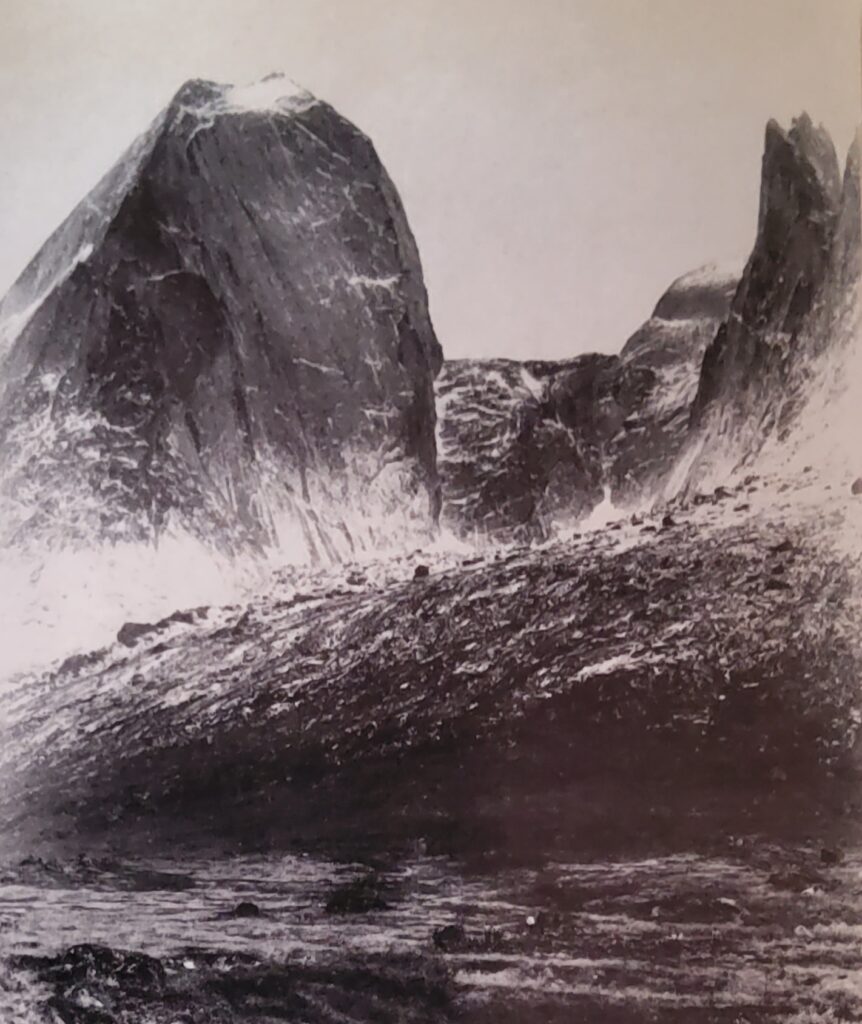

To the eyes of a man born in Norway the, western coast of Greenland had perhaps a home-like look. In the year 982, Eric the Red and his small band of Vikings rowed up a fjord, to this day called Ericsfjord and found, hidden behind the barren cliffs, slopes and valleys, where the grass grew lush, in the long Arctic daylight.

Eric was not actually the first Norseman to visit Greenland. Some eighty years before, an Icelander named Gunbjorn, had sailed along the glacial east coast of the island. Gunbjorn, however, judged the land to be uninhabitable. Eric was now testing this verdict and disproving it. He sailed farther west, than the boldest of earlier navigators and spent three full years, in systematic exploration.

Only after this long expedition was Eric able to return to Iceland, for his period of banishment was over. He had been called the Red, not for his red hair alone, but also for the blood on his hands. Even among a people as quick as the Vikings to take up the sword or battle-axe, Eric and his family were noted for their feuding. When his father was exiled from Norway for a killing, the family emigrated to Iceland. After a couple of his serfs had offended a neighbour and been slain, Eric fought that neighbour and killed both him and another. For this offense, he was driven out of the region.

Eric, however, had married a wealthy man’s daughter, Thjodhilde and he moved to her lands, in another and richer part of Iceland. While he was building his house of stone and sod, he entrusted to a neighbour, his wooden beams — treasures in a land where wood was scarce. When he wanted them back, the neighbour refused to return them and in the fight that followed, Eric killed two of his neighbour’s sons. At the spring moot — the assembly of free men, where cases at law were tried, Eric had the backing of his wife’s family and other powerful friends. His punishment for the second double slaying was fairly light: three years in exile.

He used those years in a brilliant feat of explorationtion. Perhaps, even more brilliant was his calling the new island by so deceptive a name. For on his return to Iceland he invited his countrymen to join him in colonizing the fertile valleys of “Greenland”, maintaining that “men would be much more eager to go there if the land had an attractive name”. Eric was evidently a gifted promotor. He persuaded some five hundred persons to sail, with their cattle and equipment over perilous seas, to establish a colony in a land that they had never seen. Of twenty-five ships that sailed from Iceland that summer, only fourteen arrived. The others were either forced back or lost en route.

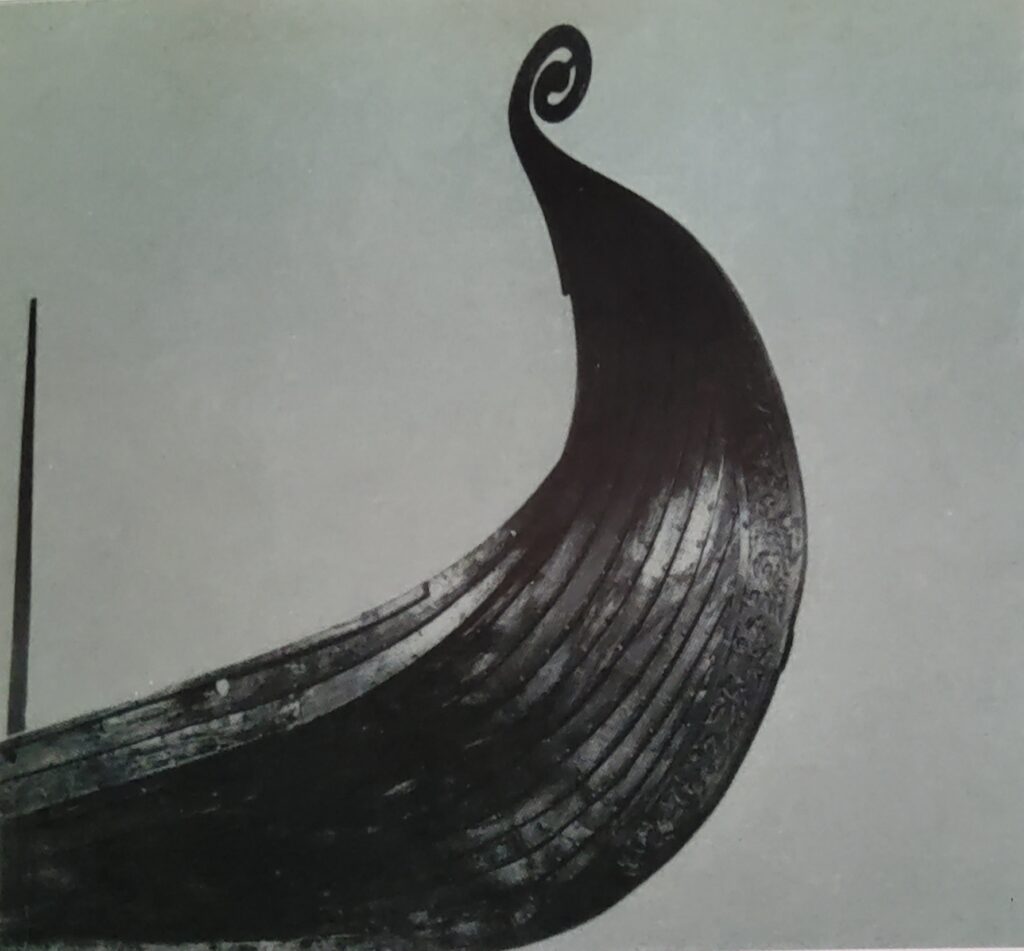

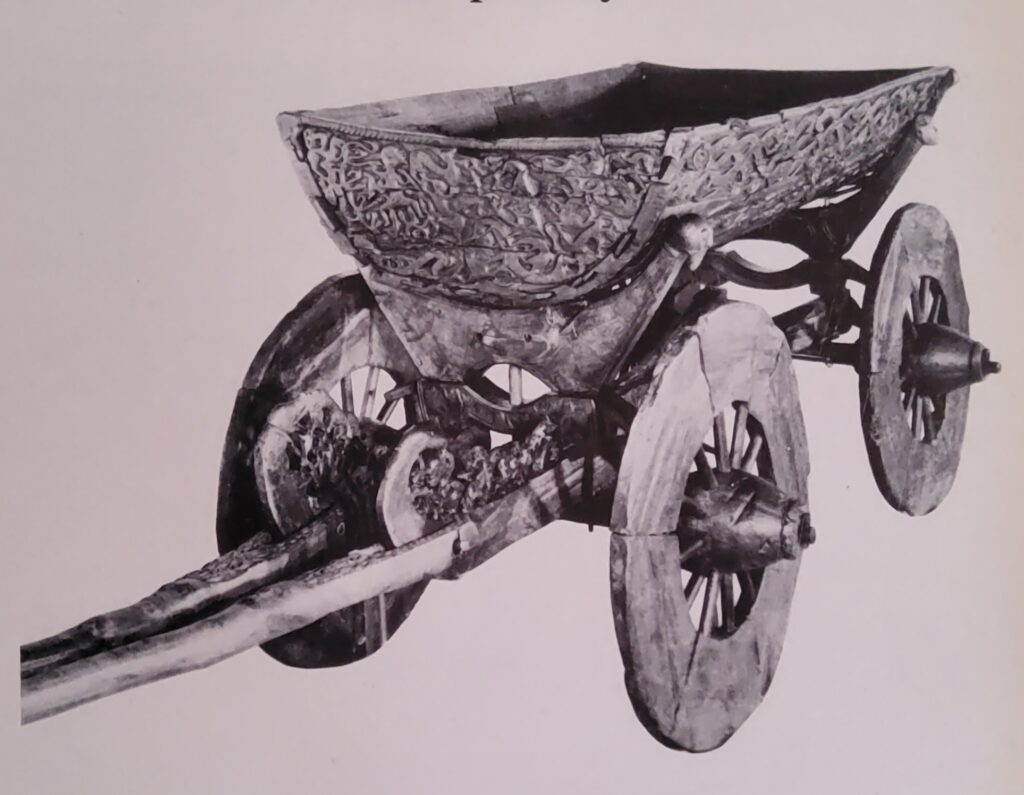

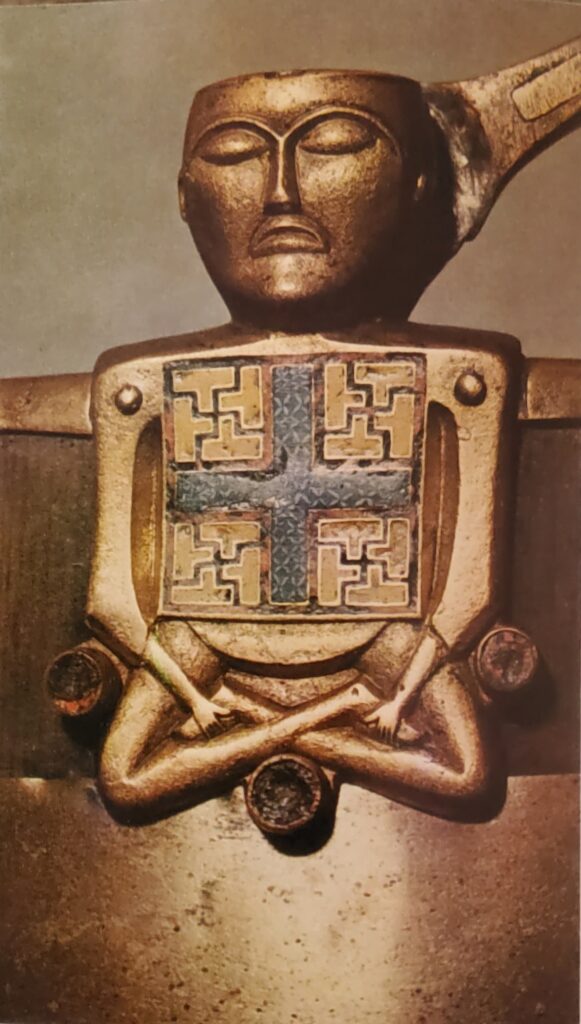

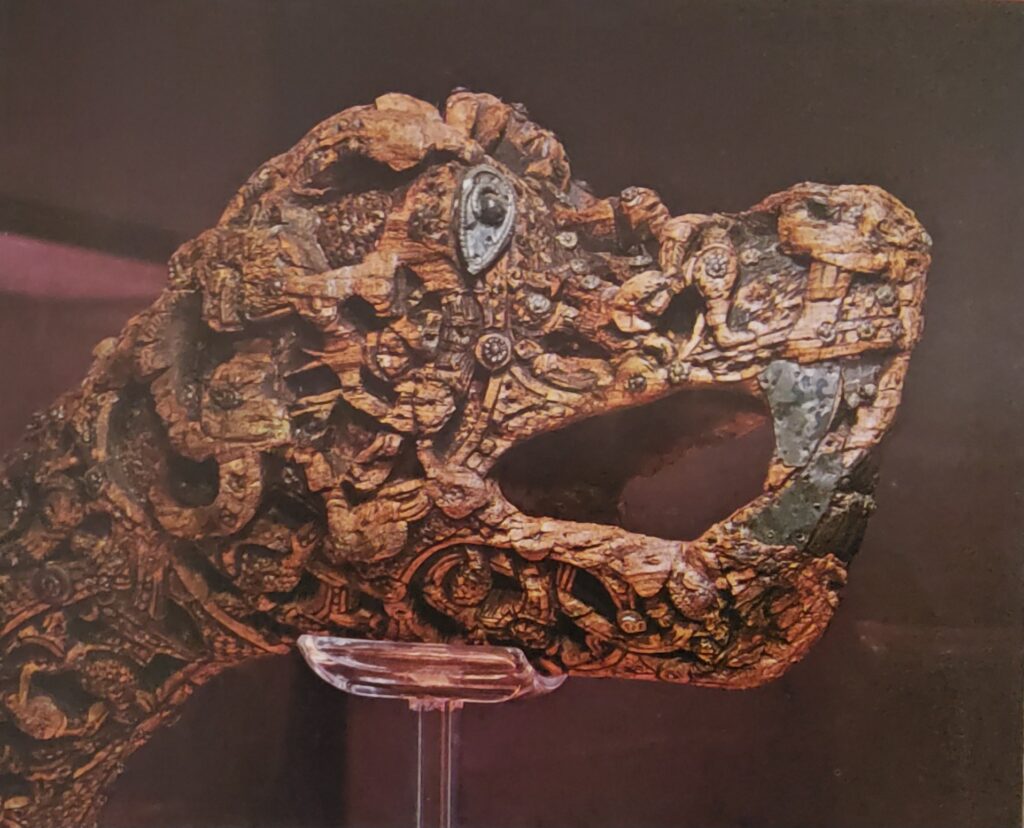

Yet the Viking ships were probably the finest in the world at that time. Viking craftsmen knew how to shape and fit the narrow planking of the hulls for speed, strength and water-tightness. Though the planking was only an inch thick and thus light and flexible, it withstood the battering of the Atlantic waves. The shipwrights had iron and steel tools, but no iron was used to hold the vessel together: ribs and planks were joined with pineroot pegs. Wide and low amidships, with deep keels and even deeper side-rudders, these ships could resist the currents of the sea and sail almost directly into the wind. Prow and stern curved high out of the water surmounted by the gleaming dragon’s head and pronged wheel-like dragon’s tail that were meant to frighten, both human foes and evil spirits.

Members of the colony proceedecd in various traditional ways to the “land taking”. Some consulted fate by throwing their wooden beams overboard and settling wherever these drifted ashore. Eric, however, made his home on the most fertile spot in the whole country, which suggests that he was a man who left little to chance. He called his farm Brattahlid (Steep Slope) and it became at once a kind of headquarters for the colony.

It was Eric’s son Leif who brought Christianity to the Greenland colony. On a voyage to Norway, he drifted off course to the Hebrides, where he stayed a winter, fell in love and perhaps was converted. When he finally reached Norway he was officially baptized at the court of King Olaf Tryggvason, who was himself a recent convert. Olaf gave Leif a priest to accompany him to Greenland.

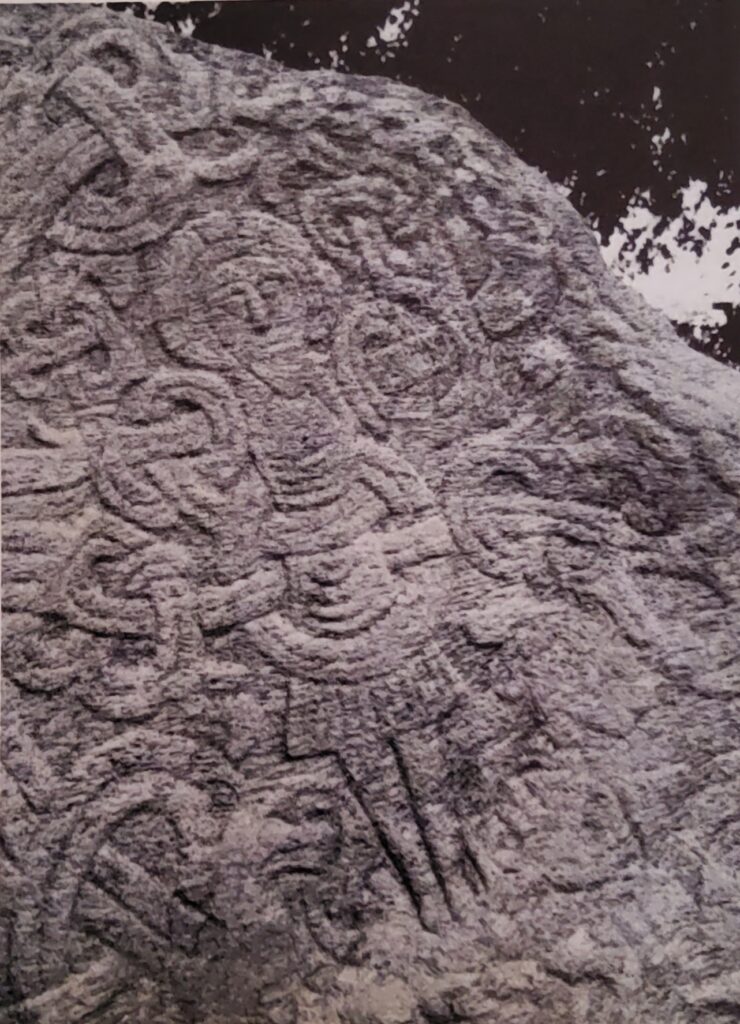

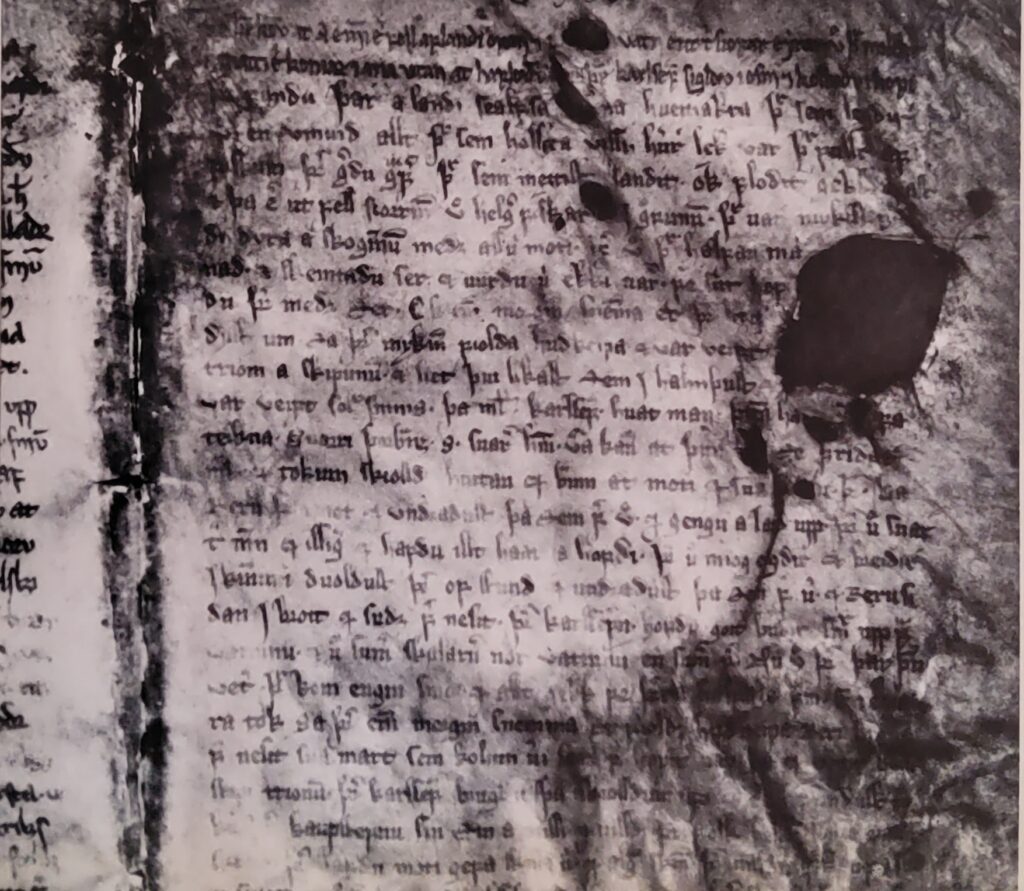

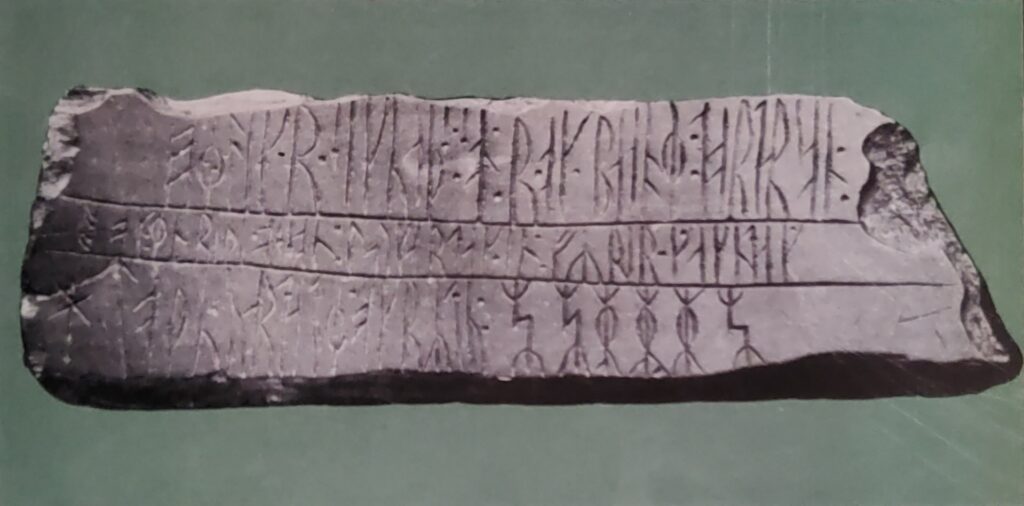

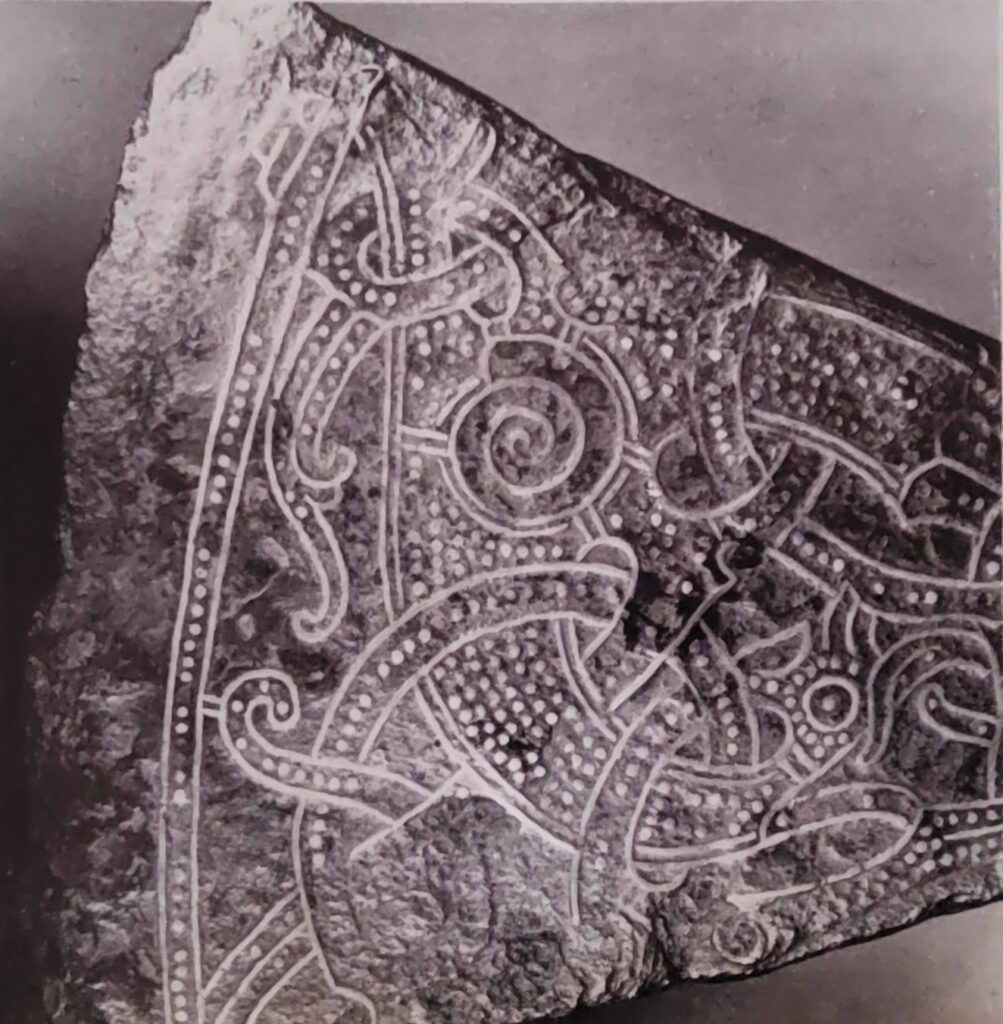

Christianity eventually overthrew the Norse gods, but for a long time the old beliefs and the forms of Norse society persisted with little change. The people continued to practice magic, divination and witchcraft. Men seem sometimes to have combined the old beliefs with the new, for tombstones have been found in the shape of the Christian cross, inscribed with prayers asking that the dead warrior may enter Valhalla. In remote Greenland, unconsecrated laymen collected the tithes and even administered the sacraments. Yet, when a man had to be buried without a priest to officiate, “a stake would be set up from the breast of the dead and in due course, when clerks came that way, the stakes would be pulled up and holy water poured into the place and a service sung over them.”

During its first century as a Christian colony, Greenland was part of the remote German diocese of Hamburg-Bremen. It was not until 1126, that Greenland received a bishop of its own who could consecrate priests there. This first resident bishop, Arnald, taught the Greenlanders how to make sacramental wine (which could also be used for other purposes) from the crowberries that grew plentifully on the high heaths. Arnald built a cathedral at Gardar — and the Greenland colony eventually had no less than sixteen parishes, with many churches, a monastery and a convent. The churches were built of huge blocks of stone in a Cyclopean style of masonry, quite unknown in Norway or Iceland. Apparently the Greenlanders borrowed the technique from the Scots.

Clearly, the colony prospered and achieved virtual self-sufficiency. The people ordinarily lived on fish, milk and meat from their scrawny livestock and on such vegetables, as they could raise in the short growing season – mainly brassicas, leeks and radishes. They had great difficulty in cultivating any sort of grain, so they had to do without beer and bread until a trading ship came in from Iceland, England, Norway or Ireland. What attracted traders to them was their walrus ivory, furs and the sturdy frieze cloth, woven from the wool of their great flocks of sheep. They took advantage, too, of the one commodity they had in surplus — time; they carved utilitarian objects out of soapstone and wood. They also made miniature walruses and boats, chess pieces, draughtsmen and other playthings.

Trade and communication with the outside world became so vigorous during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, that the colony seems to have grown to two thousand people. A population of this size must have spread out to every pocket of land usable for pasture or tillage. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, walrus ivory was a highly valued product. Papal agents travelled all the way from Lucca to Greenland to collect it, in lieu of a monetary tithe. By the fourteenth century, however, African ivory as well as English and Flemish cloth, were displacing the exports of Greenland. With shrinking demand, trade diminished sharply and communication with the outside world became more and more infrequent. Bishops continued to be appointed to the see of Greenland, but seldom resided there. A papal letter of 1492, said that they had been reduced to venerating the altar cloth, as they had no priest.

That pathetic note, is the last mention of the Greenland colony in the archives of Western Europe. What had happened to this community – seemingly so solidly established for five hundred years – to bring about its total extinction? Legends, both of Iceland and of the Eskimoes, tell us of battles with the nomadic hunters of the far north, whom the Greenlanders called “Skraelingen.” These attacked and destroyed the eastern part of the colony in 1360. According to their own story, the Eskimoes eventually destroyed the western settlement also. The last group of Greenlanders, they say, were burned down in their church.

What had happened and decimated the settlers before this however, reducing them gradually to helplessness, was the growing severity of their climate. These last settlers still had some contact with Europe, for fifteenth-century graves, reveal that their clothes were in contemporary European middleclass fashion — long gown, short cloak and hood. Their bones, however, show that their bodies were stunted by malnutrition and scurvy. The glacier, moving into their fjords, had shut them in from marine hunting; the ice rising to a higher permanent level in their soil, had destroyed their crops. Nature thus reduced all who did not join the Skraelings in their nomadic life, or as some surely did, emigrate back to Iceland or Norway. In 1540, an Icelander curiously named John Greenlander, found on the site of the west coast settlement, the dead body of a man, only wearing hood and frieze clothes. “By him lay his iron knife, bent and almost worn away.” In establishing a colony in Greenland, European man had apparently arrived at his natural limits.

Leif Ericson discovers Vinland

It is one of the ironies of history that in 1492, the very year all communication between Greenland and Western Europe ceased, a Western European rediscovered America. For, as we know, a Greenlander had found the American continent five hundred years earlier. It was Eric the Red’s son, Leif, who sailed far to the west and south of Greenland about the year 1000, discovering a place rich in grapes, which he called Vinland.

Vinland the Good, the sagas call it. Authorities debate the bearings indicated in the saga, but there is no doubt that Leif had happened upon North America. The first to follow up his exploration was his brother, Thorstein, who reached America three to six years later. Then another chief, Karlsevne, took a colony to winter in Vinland. For a Greenlander, the new country was closer than Norway. Karlsevne encountered many Skraelings — the Greenlanders seem to have made no distinction between Indians and Eskimos —and traded bright red cloth for their furs. Eventually the colonists and the natives clashed. The Indians descended in a “great multitude of boats” and although the attack was beaten off, the Vikings realized that they were too few in number, to conquer a hostile country. They sailed back to Greenland. There is no record of any later settlement, but for some time, the Greenlanders continued to visit America for purposes of trade. Perhaps they were mainly seeking wood — some of their coffins were made of larch, which is thought to have come from the American coast.

Both Eric the Red’s settlement of Greenland and Leif Ericson’s discovery of America seem to have been curious dead ends. Hundreds of colonists were willing to forsake Iceland for more remote and inhospitable Greenland; it was only a short step to the far more abundant land of Vinland. Yet no permanent colony was ever established there. Our sources are so sparse that the reasons for this cannot be deduced. Certainly the Vikings usually showed no fear of long sea voyages or of hostile populations. Their chief historic role, after all, was that of the last great invaders of Europe.

Some say blandly that “Scandinavia had nothing to contribute to European civilization” and comment on the Vikings’ taste for sacking monasteries, which were indeed the richest treasure houses they could find. They were, in their time, as dreadful as the earlier Germanic invaders were in theirs. Others have seen the Vikings as shrewd traders, craftsmen technologically in advance of the Christian world; as men who, though illiterate, expressed in their art and epic, an ample and creative spirit.

Norwegians began their first incursions into northern England in 787. Thereafter, they or their Danish cousins returned repeatedly. At first the raids came in summer; then the Norsemen built strongholds so that they could winter in the land. Later, they took possession of whole districts of England. Other Vikings drove the Celtic hermits out of the far northern and western islands and likewise overran most of Ireland. Dublin and Limerick fell to them and for a few short years — from 834 to 841— Norsemen ruled a unified Ireland. Central government did not survive, but for a long time the Norwegians kept firm regional control of the country. After 845, the chronicler says “there came great sea-cast floods of foreigners” to Ireland.

In 842, meanwhile, the Danes sacked London and Rochester. They expanded the “Danelaw” — the countries in which Danish law prevailed — until it embraced all England. At the same time, other Danes were transforming Frisia and the Netherlands into bridgeheads for deeper incursions into the Holy Roman Empire and into France. They sacked Utrecht, Nantes, Bordeaux and Paris, to name only some of the major towns. In the 860s, Paris fell again: “The number of ships grows,” a chronicler wrote. “The endless stream of Vikings never ceases to increase. Everywhere the Christians are victims of massacres, burnings and plundenngs.” The Vikings looted the city, established themselves on an island in the Seine and were only driven away by other Vikings who had been bribed by French lords. Then in 886, came another siege of Paris: “The town trembles and horns resound, the walls are bathed in floods of tears, the whole region laments, from the river are heard the horn blasts”.

While Vikings thus pushed up the rivers of France from both the North Sea and the Atlantic, laying waste the land and especially the towns, other Norsemen sailed past Gibraltar into the Mediterranean. In 860. Pisa and Lucca fell to them, were looted and left to their lamentations. Another expedition about the same time plundered Lisbon and Cadiz. Twice the same band of Vikings rowed up the Guadalquivir and sacked Seville. Finally, they were driven off with the loss of many ships and men, but the survivors managed to regroup in France and to carry some Moorish captives, “blue men”, into Ireland. Meanwhile, the Swedes exploded eastward, to conquer and rule the “land of the cities” that they found flourishing in western Russia, along the Neva and Dnieper rivers. “We called them in to settle our quarrels and rule over us”, a later Slavic chronicle explains. It is true, that the conquerors’ rule first unified this land. In 865 these Swedish princes, known as the “Ros”, organized a fleet that sailed down the Dnieper and across the Black Sea to besiege Constantinople. Only a storm, attributed by the inhabitants to the intercession of the Virgin, saved the Eastern capital of Christendom.

Danegeld — a bribe to keep away

The Vikings sometimes agreed to forego pillage in return for regular tribute. As early as 810, Gottfrid of Denmark, invaded Frisia with a fleet of two hundred ships and broke down the defenses organized by Charlemagne. He extorted from the local lords a tribute of one hundred pounds of silver. In subsequent raids on the Frankish lands, staggering sums were collected. By 926, the Frankish kingdom had paid thirteen danegelds or tributes. Seven of these payments are known to have amounted to 39,700 pounds of silver. The regular levies of danegeld in England, were patterned on the Frankish example. In order to pay off the invaders, the Anglo-Saxon kings imposed on their subjects the first regular tax in English history.

Yet, the Vikings could not always be bought off, because often tribute only whetted their appetite. Their kings and chieftains had little control over the young warriors who organized marauding expeditions. Such expeditions formed part of the usual education of the young Scandinavian aristocrat and often the basis of his further fortunes. Later sagas explain the Viking conquests of England and Ireland as the work of vassals rebelling against the feudal authority of kings at home. Such explanations spring from an age in which feudal ties were more binding. The original movement, in fact, was chaotic and diverse. Norsemen were attracted by the political weakness of the Carolingian empire. In one instance, two of Charlemagne’s sons invited them to fight the third. Usually, however, they did not wait for invitations, nor did they obey when their kings commanded peace. In general, the invasions appear to have been the response of a multitude of local aristocrats to land hunger and the pressure of overpopulation. The Viking expansion was a kind of Völkerwanderung by sea.

By 875, the Norsemen seemed to have surrounded Europe. They attacked it from every quarter and seemed on the point of conquering the entire continent. The century of raids was followed by a second century, during which the invaders settled into the society that they had conquered. In the West they became lords of Frisia, Flanders, Normandy, most of England and Ireland. In the East, they introduced political unity to Russia by distributing cities among the brothers of a ruling house. They followed the odd practice of rotating the seats of power among the rulers whenever one of the princes died. The Vikings also assimilated the language and much of the culture of the Slavic milieu. By the year 1000, Byzantine missionary work had converted the Norse princes and the Russian populace to Christianity.

In Western Europe, effective resistance to the invasions followed the establishment of centralized governments. New kingdoms were organized independent of the decaying structure of Carolingian authority and the Norsemen were contained. By driving the Danes back to the Humber, Alfred of Wessex became the only king in English history to receive the epithet of “the Great”. Reconquest of much of the Danelaw by Alfred’s sons and grandsons permitted the development of an English monarchy that ruled over a mixture of Anglo-Saxon and Christianized Danish subjects. Similarly, in France, Count Oddo of Paris in 887, drove a besieging force of Vikings back to Burgundy. This sort of resistance paved the way for the famous treaty between Rollo the Norman and Charles the Simple, in 911. Rollo received all the region of the lower Seine — henceforth known as Normandy — on condition that his men defend the land, receive baptism and do homage to Charles as their overlord.

The treaty tacitly assumed that the Norsemen would continue their raids on Brittany; the Bretons had to establish a line of defense themselves. The Normans soon acquired the language as well as the religion of their subjects and their nominal overlords. They also acquired outstanding skill as horsemen and as builders of forts and siege machinery. Firmly bound by feudal ties of allegiance, they became in the eleventh century the conquerors of England. In the same period, they sent an expedition into Sicily, which with the blessing of the Pope, seized the island from the Moors and founded a new south Italian kingdom. As in other places, the Vikings native talent for war and government remained in evidence long after they were fully absorbed by the language, the economic system and the culture of their new land. A similar pattern of resistance and assimilation may be seen in Ireland, where in 1014, Brian of Munster defeated the Norse kings of Dublin; after this, the Norsemen became part of the complex tribal society of Ireland and dominated some of its cities, but their role of alien masters had ended.

The Danes invade England

At this very time, the Danes invaded England once more and almost gave a pax normana to England. From 1013 to 1042, King Canute and his sons undid the work of Alfred the Great. They tried to unite what remained of the Danelaw, Anglo-Saxon England, Scotland and Denmark under a single Scandinavian king’s rule. Quite different from the old-style Viking raids, this was a unifying operation by a strong monarchy, no longer pagan, but Christian, “Merry sang the monks at Ely as Cnut the king rowed by”.

In history, the Vikings remain an experience on the poetic fringe of the European memory. Perhaps because they were the last incursion of an unlettered and pagan people upon the Europeans, they left the impression of a primal tribe of brothers: rapacious, lusty, loyal to their chiefs and to each other, but given also to rebellion and fratricide. Yet they were skillful craftsmen and energetic traders who eventually governed thriving cities. In war they were subject to the madness they considered divine, the “going berserk” that doubles a man’s strength and makes him immune to pain. In the names of our Wednesday, Thursday and Friday, we still do honour to their three chief deities: Odin, Thor and Frey. Odin: the subtlety and craft that built their ships, guided their merchants, taught their sailors the use of arms, horses and forts. Thor: the thunder god of violence. Frey: the god of fertility who made men rich in kinsfolk and ever poor in land. All are implicit in the three symbols sacred to Thor: the hammer, the battle-axe and the sacred ring. These gods symbolize forces that drove the Vikings to exploration and conquest, forces not unrelated to the European “restlessness” that ultimately drove men to navigate and conquer most of the globe.