Toledo falls and this marks the beginning of the end of Islam in Spain.

A triumph for orthodoxy

The events at Canossa and the condemnation of Peter Abelard under the auspices of St. Bernard of Clairvaux, were signal triumphs for the papacy and the orthodox doctrincs of Western Christianity. The capture of Jerusalem by the First Crusade, on the other hand, was an exhilarating achievement for European Christendom as a whole. Yet, during these sixty-three years, new forces emerged, forces that led to questions about the spiritual status of the ecclesiastical hierarchy and even about the fundamental doctrines of the faith. Meanwhile, the successes of the crusaders diminished and the Latin states that they had established in the Levant, fell into a decline in which even Bernard himself was implicated.

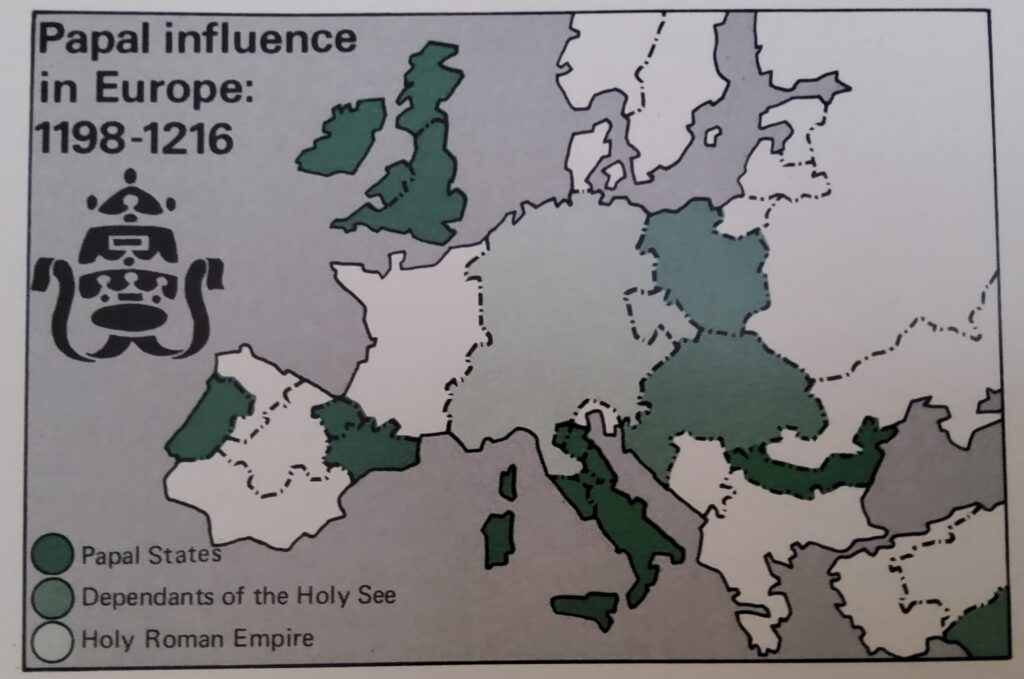

Within ten years of the humiliation of Emperor Henry IV, Pope Gregory VII ended his days in exile from Rome, supported only by the Norman army of adventurers that he had called to his aid. Although his great rival was to end his reign opposed by a papist party supported by his own son, that son, Henry V, soon demanded in his turn, the rights of clerical investiture claimed by his father. The conflict was not resolved until the compromise of the Concordat of Worms in 1122. Its terms approximated the terms won by the Emperor’s father-in-law, Henry I of England, some fifteen years earlier. In return for surrendering the right to invest bishops with the spiritual symbols of their office, the rulers won papal recognition of their right to have an effective voice in the election of bishops. As it stood, discord between the Church and the secular authorities was to remain potentially explosive for generations to come. Indeed, there were many people in Europe who deplored what they regarded as the worldliness of the Church.

Arnold of Brescia

During the eleventh century, a movement had sprung up in Lombardy devoted to an ascetic and “primitive” Christianity and known as the Humiliati. However, the opposition among the public at large, to the growing secularization of the Church, was most dramatically embodied in the career of Arnold of Brescia.

Probably a pupil of Abelard and condemned with him at Sens, Arnold preached that only the lay power should own and administer property. In the last years of his life — before his execution at the order of the Pope — Arnold led a republican government in the city of Rome itself. Arnold’s ideas, though politically subversive, were not as serious a challenge to the authority of the Church, as was the intellectual unrest abroad during the twelfth century, an unrest symbolized by the career of Abelard. Arnold, indeed, had not been killed as a heretic; nor were the Humiliati, who after all claimed only to be returning to the teachings of poverty of Christ himself, at first open to charges of heresy. However, the case was quite different with the sect known as the Cathari, whose successors were the Albigensians of southern France.

The doctrine of the Cathari was less of a heresy within the Christian Church, than it was a rival religion. It must therefore be regarded as one of the most serious manifestations of the new ideas abroad in Europe during the twelfth century. The Cathari had originated in the Bulgarian lands of the Byzantine Empire and their beliefs show the strong influence of Eastern thought, as found in the teachings of the Persian Mani. They saw the world as the battleground of two equally powerful forces of good and evil; and regarded the physical creation of the world as the work of the evil one. Thus rejecting God’s role in the creation, they overthrew one of the fundamental doctrines of Christianity.

The speculations of an Abelard and the humble aims of the Humiliati in no way tended to the extreme anti-Christian position of the Cathari. Yet their searching questions into the substance of orthodoxy could only be regarded as menacing by the ecclesiastical establishment. The Church was in habitual political dispute with the lay power and was constantly on guard against the subversion of heresy.

The threat of Islam

In the twelfth century, religious speculation, as St Bernard feared and foresaw, was not to be easily stopped. A substantial contributory factor to such speculation was Islamic civilization. It is true that in Spain Islamic culture had flourished on European soil for centuries, but it was only in the newly confident and outward-looking society of the twelfth century, that all the conditions were right for Europeans to profit from the rich store of Greco-Arabic learning that had been on their doorstep for centuries. The movement had been gathering momentum throughout the previous century and now, the Arab influence was readily accepted.

The monk Gerbert, who became Pope as Sylvester II, had been the first Westerner to use the “Arabic” numerals and it was probably he, who introduced the astrolabe for astronomical experiments into Europe. At Salerno and then at Monte Cassino, thanks to the writings of men such as Constantine the African, the principles of Greco-Arabic medicine were being studied in Europe. Islamic thought, with its bases in the works of Aristotle and Plato and the science of India, was immensely influential in the early twelfth century at the great school of Chartres and direct contact with the Greek texts of the ancient philosophers was possible for such Western scholars as James of Venice, who studied at Constantinople. The main impetus was from Islam and above all from the cosmopolitan courts of newly Christian Spain.

There, Arabs, Christians and Jews combined to initiate a revolution in mathematics that was to culminate at the end of the century in the career of Leonardo of Pisa. The much-travelled English scholar, Adelard of Bath, spent many years in Syria and Spain. His numerous important translations include the first Latin version of Euclid. Adelard, in fact, was one of those who introduced the new Arabic writings on the study of alchemy from which European chemistry was to spring. Europe’s contacts with the East and the Arab World were probably also crucial to the development of the Gothic style in architecture.

It is interesting that the impact of Arabic culture on European thought seems to have been at its greatest during the period when the Christian kingdoms of Spain were enjoying their greatest success in the long process of reconquest. Toledo, the ancient Visigothic capital, was recaptured in 1085 and by 1100, the combined kingdoms of Castile and Leon had pushed their frontiers well to the south of the Ebro River. Their advance was slowed during the twelfth century when the Moorish emirates in Spain were united under the Murabit dynasty.

Spain reconquered

The Spanish victories were important, but they were no compensation for the massive blow suffered by the Christian cause in the East at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. Here the Byzantine Emperor Romanus IV was defeated by the armies of the Seljuk Turks and the whole of Anatolia, the vital hinterland of Constantinople and Christendom’s eastern bulwark, was suddenly put in jeopardy. The defeat in part had been due to treachery, as civil war compounded the troubles of the Empire. Now numbered among her external enemies was a new force, the Norman principality of southern Italy.

The domestic conflict of the Eastern Empire ended with the accession of Alexius I Comnenus in 1081. He was able to foil the Normans by a diplomacy that included an alliance with – and important trading concessions to – the growing power of Venice. However, Constantinople itself was threatened by the depredations of nomadic tribes from the Asian steppes. Nevertheless, by the early 1090s, thanks to the Herculean efforts of Alexius, the Empire, although much reduced by the events of the previous twenty years, seemed to have weathered the storm, but a new problem now appeared.

Earlier in his reign, in his search for allies, Alexius had appealed to the West for mercenaries. With the arrival of the crusaders in the European provinces of the Empire in 1095, Alexius found himself with a force that threatened to overwhelm rather than support his realm. Instead of mercenaries, of the kind Byzantium had used for centuries, came a host of landless barons and footloose adventurers inspired with hatred of the Infidel, hope of eternal salvation and little respect for the “schismatic” Christian Emperor of the East. This vast and fervent body of men was under the command of a group of ambitious princes who included Alexius’ old enemy, Bohemond the Norman. Nevertheless, the Emperor succeeded in transporting the crusader army away from his capital to Palestine. In addition, he exacted from most of the leaders an oath of homage for any lands that they might recover.

Among those to swear was Bohemond; but his subsequent attempt to hold Antioch as an independent principality led him at one point to call for a “crusade” against the Christian Emperor of the East himself. Such corruption of the spiritual ideals of the crusade was to be a dull thread throughout its history, but even from the outset, the motives and motivations of the crusaders had been mixed. What was the nature of the newly confident and aggressive Europe from which they came?

The Crusaders

Undoubtedly, the religious impulse was strong. The crusade was launched by the stirring call to liberate the Holy Places made by Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermontin 1095. While Jerusalem had been controlled by the Arab Fatimid dynasty, access to the city had been comparatively easy for the growing flood of Western pilgrims, who were inspired by the new mood of piety abroad in Europe following the monastic reforms of St. Bernard. With the conquest of Palestine by the fanatical Seljuks, advancing in the wake of their victory at Manzikert, the pilgrim routes were cut.

Although the religious intentions of Urban II need not be questioned, he must have been aware of the massive increase in the prestige of the papacy already high after Canossa, that would follow from the recovery of Jerusalem under his aegis. Urban’s call rang throughout Europe and was taken up by itinerant preachers such as Peter the Hermit. Indeed, Peter led a vast but disorderly band of common people to the crusade and despite his own obscure and humble origins, he enjoyed some prestige with the army. Although the later crusades were to be led by kings and emperors, the first was undeniably a popular movement, even though most of its aristocratic leaders may have had ulterior political ends of one kind or another.

Crucial as religious idealism and land-hungry ambition were to the success of the crusade, underlying both idealism and ambition was the fact that for more than a century the population of the West had been growing at an almost explosive rate — possibly because of improvements in the dietary regime of the whole population. The dynamism and expansionism of European intellectual and political life can be observed, but it is impossible to measure precisely the dimensions of the population expansion that it reflected. We know that during the tenth and eleventh centuries, vast new areas of forest and marsh had been reclaimed for agriculture within the traditonal frontiers of Christendom; and that the vast movement of colonization of the lands to the east of the German empire had begun.

The growth and increasing physical vigour of the peasant population that these facts indicate were caused, at least in part, by a revolution in agricultural machinery and techniques. In this revolution there were three vital elements that gradually merged: the development of a new plough, more capable of turning over the heavy and fertile soils of the northern European plain than its predecessor; the introduction of a new system for the rotation of crops, which made for a more efficient use of land and also made possible the introduction of new crops with higher protein content; and the gradual adoption of the horse as a draught animal, in place of the more slow-moving oxen of previous generations. The combination of these three factors created a new situation in northern European agriculture, which has been viewed as the basis of the cultural ascendancy of the north, above all of France, throughout the Middle Ages. There can be no doubt that the new agriculture played an important part in European life of this period.

In saying this, however, we do not forget that it was the new spirit of inquiry abroad in Europe, that enabled the splendidly vigorous society of the twelfth century to adopt the new learning and evolve for itself a new intellectual orientation.