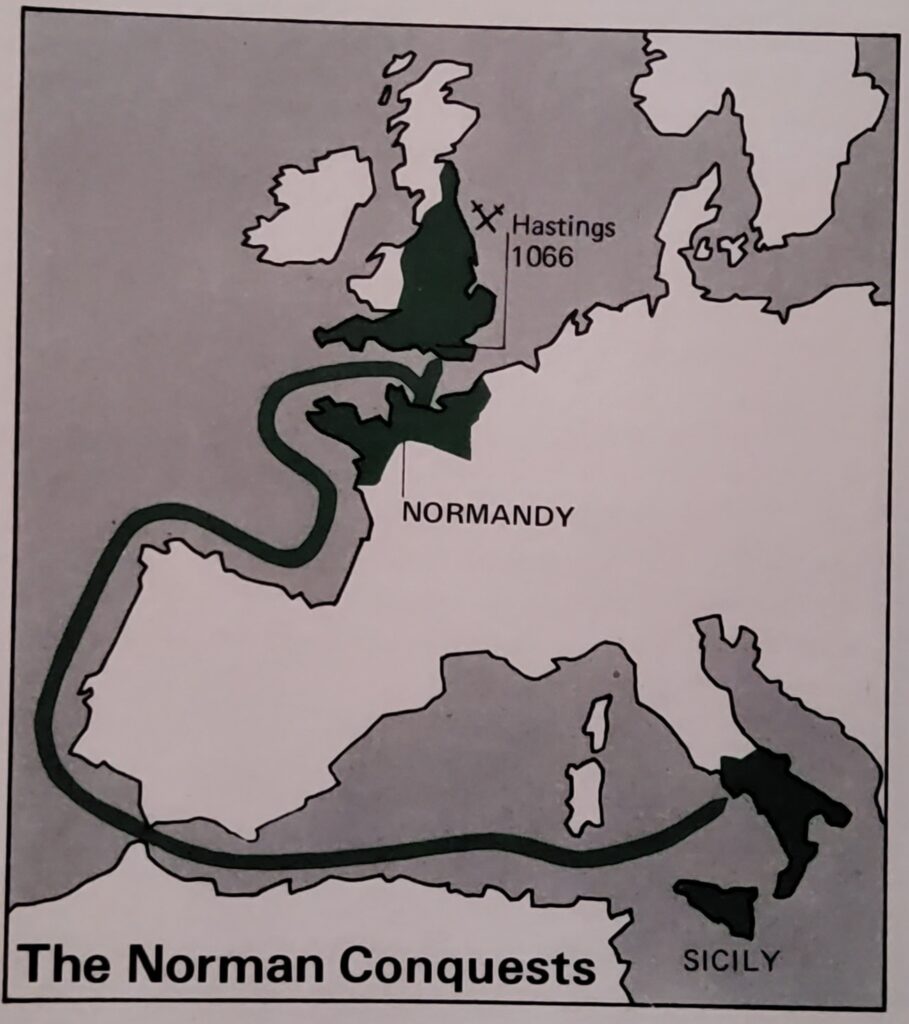

William of Normandy, the conqueror, was also descended from English kings and was convinced that King Edward had promised him the succession. The disputed succession following the death of King Edward the Confessor, brought new invasions and new wars to England. Then two great battles fought in the fall of 1066, decided the country’s future. At Stamford Bridge, Harold, King of England, defeated his cousin and namesake Harold of Norway. His joy was short-lived; immediately after the battle, King Harold learnt that another cousin and claimant to the throne, William of Normandy, had crossed the Channel from France and had landed, only one hundred miles away. Overconfident after his recent victory, Harold rushed south with half his army, but was soundly defeated by William of Normandy at Hastings. Although undertaken with the blessings of the Pope, William’s invasion was in a sense, the last great Norse conquest and ironically, it brought England more closely into the orbit of continental Europe.

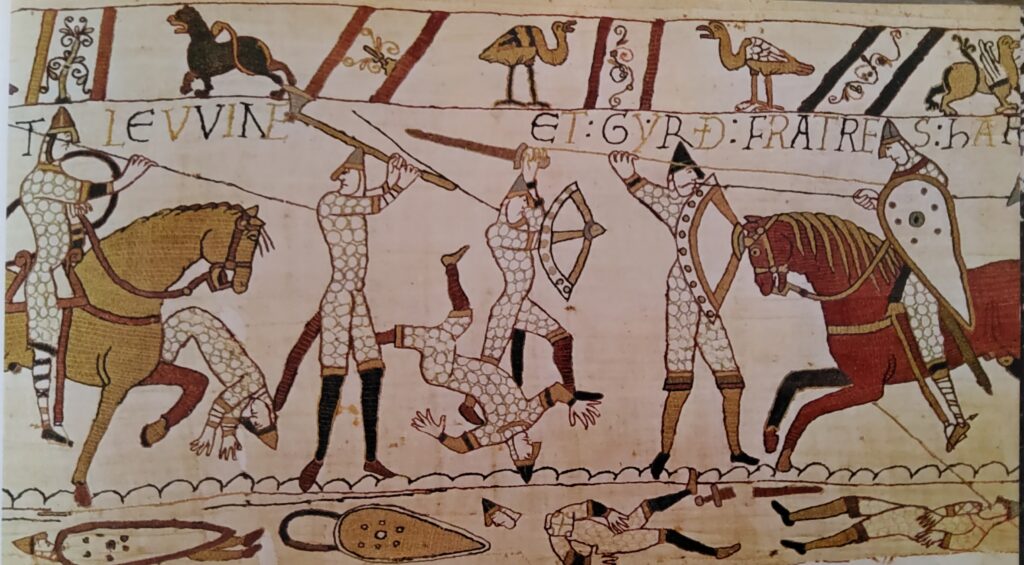

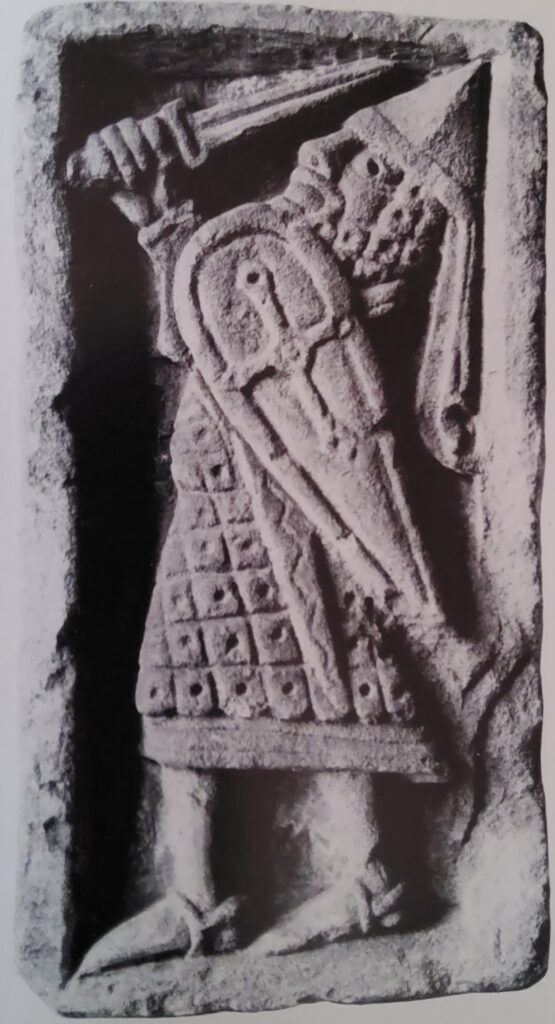

At about nine o’clock on the morning of October 14, 1066, two armies of approximately equal size, faced each other across the valley between Telham Hill and a nameless rise, marked by the presence of a “hoary apple tree”, close to the modern town of Battle. William, Duke of Normandy, commanded a motley host of Norman retainers, Breton allies and Flemish mercenaries — the majority of them adventurers, whom he had persuaded to cross the Narrow Sea for loot and land. William of Normandy’s army has been estimated at somewhere between six and seven thousand men; it was probably nearer the lower figure. Perhaps 1,200 of these were mounted knights, who had brought their horses with them in the boats. The rest were infantry and included an unusually large number of archerers. The knights wore heavy hauberks of leather – plated with rings of metal, reaching to the knees and their legs were protected by high leather boots. In battle, they used swords and lances. The ecclesiastics among them, such as William’s half-brother Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, wielded maces. A mace could crush a man’s skull sine eflusione sanguinis — without that shedding of blood, which the Church forbade to clerics.

Harold of Wessex, King Harold II of England, had perhaps a thousand more men than the Duke, drawn up in tight formation around his two standards: the Dragon of Wessex and his personal banner, the Fighting Man. The nucleus of this force consisted of professional soldiers: Harold’s housecarls, who were armoured like the Normans. There had been much Norman influence in England since the accession of Edward the Confessor, who had grown up in Normandy and the armourers of England, had learned from their fellows across the Channel. Harold however, had ordered his professionals to dismount, in order to stiffen with their shield-wall, the levies of inexperienced men hastily assembled from London and the vicinity. The latter were armed with whatever they had: slings, axes, javelins, even hammers and scythes. The housecarls relied on their Danish pole-axes — fearsome weapons — and on spears used either for throwing as javelins, or as lances to turn charging horses and unseat knights.

Harold’s men were tired. They had marched the sixty-odd miles from London in two days and had taken up their positions only the previous night. Harold himself and the housecarls were even more weary than the levies; in the course of the past month, they had covered nearly four hundred miles from London to York and back again, having fought a great battle. For 1066, the “year of the comet”, had seen other invasions besides Duke William’s expedition.

According to medieval belief, “the star with hair” portended the death of a king or the destruction of a kingdom. Certainly Halley’s comet, which shone in the skies over England at the end of April, 1066, justified all such fears. King Edward the Confessor, had died at the beginning of January and Harold Godwinson had been crowned as Edward’s successor, on the day of his funeral. (Whether you thought this right or wrong depended on whose partisan you were.) There were at least three other strong candidates for the throne. Closest in descent from the English royal line as well as the line of Norman dukes, was Edgar the Atheling, but he was still a boy. Another candidate was Harold Hardraada, King of Norway, who had formed an alliance with Harold Godwinson’s brother Tostig. Tostig had recently been deposed from his earldom of Northumbria; he seems to have been of a treacherous and vicious disposition and had roused the whole countryside against him. The strongest claimant of all, was William the Bastard of Normandy, who was also descended from English kings and who was convinced that King Edward had promised him the succession.

King Harold marches south to Hastings

During the last years of Edwards life, however, Harold had been the effective ruler of England. That was why he had been able to seize the throne so quickly and in the nine months and nine days of his reign, he succeeded in consolidating his popularity. To quote one of his supporters, he “abolished unjust laws and made good ones, patronized churches, monasteries and showed himself pious, humble and affable to all men”.

He also proved to be a remarkably good soldier and a foresighted organizer. When soon after the appearance of the comet — his brother Tostig raided the Isle of Wight and harried the southern coast of England, Harold rushed down to Sandwich from London and drove him away. Then, hearing that William of Normandy was gathering forces to make good his claim to the throne, Harold posted ships and men all along the coast and kept them there through the summer. Only a few generals or kings in those days could master the logistics of large standing armies. By early September, provisions had run out. Moreover, the danger seemed past; spring and summer was the time when “kings go forth to war”. Harold allowed the men of the fyrd, the national levy of Anglo-Saxon England, to disband on September 8. He himself returned with his ships to London, disastrously losing many of them in the same storms that were keeping William the conqueror of Normandy, from crossing the Channel.

The dissolution of the army came at the worst possible moment. Barely back in London, Harold learned that his Norwegian namesake, Harold Hardraada, had invaded the north. Tostig had joined forces with him and in a fierce battle at Fulford the English traitor, the Norwegian king and a mixed force of Norwegians and Flemish mercenaries, had crushed the defending English led by the earls of Mercia and Northumbria. Southern England seemed to be wide open to invasion.

Harold at once set out for the north with his housecarls. He must have gathered up the dispersing fyrd as he went, for by the time he reached York, he is said to have had an army of “many thousand well-armed fighting men”. He covered more than two hundred miles at such speed, that he caught the Norsemen and their allies by surprise. On September 25, 1066, the armies met at Stamford Bridge. The Norsemen, though weakened by Fulford, which had been a costly battle for both sides, fought ferociously. It was Harold who achieved complete victory; both Tostig and King Harold Hardraada were killed and the bulk of the invading force destroyed. The comet had truly foretold the death of kings, but its influence had evidently not yet waned. Harold had also lost many of his best men and in the midst of his triumph, he learned that the Duke of Normandy had landed at Pevensey. With his mounted housecarls, Harold returned to London at top speed, leaving the rest of his army to follow at slower pace.

William of Normandy was at this time approaching his fortieth year. Brutal, avaricious, ruthless, consumed by ambition, he was also a courageous and resourceful leader, a magnificent administrator, a pious Christian and a good ruler, who used tyranny to achieve the ends of stern justice. He had overcome the handicaps of bastardy and a frightful boyhood under savage tutelage and had clawed his way to unchallenged power in a duchy racked by dissension and treachery. Two years before, he had tricked or forced Harold Godwinson into swearing to support his claim to the English throne. As soon as Harold seized the crown, William initiated a skillful propaganda campaign in all the courts of Europe, accusing the new king of perjury. He secured papal blessing for his expedition to punish the “oath-breaker” and at once began gathering men and building ships for the invasion of England. Unlike Harold, he succecded in holding his forces together for six dreary weeks, while he waited for contrary winds to change, enabling him to cross the Channel with his host. His big, navy ships, built to carry horses and ponderous equipment, were propelled only by sails, not by oars.

Although he did not know it, the delay was providential. Had he embarked when he was ready, he would have encountered an intact English navy and coastal guard and might never have succeeded in landing. As it was, When the wind finally shifted to the south and the Normans disembarked at Pevensey, they met no opposition. By the time Harold, with fatal impetuousness, reached the Sussex Downs with his available men — half his army had not yet come up; one chronicler asserts William was fully ready for him. Nevertheless, the Normans had the disadvantage of terrain: they would be attacking uphill against the English and William could not take the risk of avoiding battle, for Harold’s army was blocking the road to London. It was clear that the English would only grow stronger with each passing day, for they had vastly greater resources. Good sense could only have urged Harold, for his part, to wait, retreat, draw the Normans deeper into a hostile countryside, but he chose to fight– perhaps from overconfidence after his recent victory, perhaps to save his lands from further pillage.

The story goes and it is a pretty one, though it may not be true that the first blow on the Norman side was struck by the minstrel Taillefer, who rode in the van performing juggling feats with his sword and “singing of Charlemagne and all his men.” (Perhaps he sang an early version of The Song of Roland). The mounted Norman knights formed the centre, just as the English had the housecarls in the centre of their line. On William’s left were the Bretons; on his right, Robert of Beaumont — one of the heroes of the day — with a mixed force of Flemings and French. The infantry advanced first, sending a rain of arrows into the English shield-wall and receiving all kinds of missiles in return. Then the Norman cavalry attacked, but they were toiling uphill against superior numbers and the English line stood firm. The terrible slaughter, the ferocity of the hand-to-hand combat, the slain being stripped of their armour in the midst of the carnage, all this is vividly depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry.

The Tide of the Battle Turns

After suffering heavy losses, William’s forces broke and retreated in confusion. William himself had his horse killed under him (he lost three in the course of the day) and the rumor spread that he was dead. Harold’s undisciplined levies broke formation to pursue the fleeing enemy. In this crisis, William snatched off his helmet to show himself to his men. “You are throwing away the victory!” he shouted — and together with his brother Odo, he succeeded in rallying the knights. The mounted Normans, with their superior mobility, quickly surrounded the isolated detachments of Englishmen and cut them down. The incident had given William the key to the battle. Now he ordered his men to feign flight and twice the ruse succeeded. Then the Norman army resumed its struggle against the thinned English ranks. In the final assault, William commanded his archers to shoot high, so that the arrows flew over the protecting wall of the housecarls shields. Simultaneously, his cavalry charged. Still the English fought on until Harold himself was killed, perhaps in the melée, perhaps by a fortuitous arrow that struck him in the eye. His two brothers had already fallen and with their leaders dead, the English soldiers lost heart. At nightfall, they began to flee in disorder. The battle that decided the fate of England, was over.

The Battle of Hastings did not spell the end of English resistance, but it definitely transformed the Duke of Normandy into William the Conqueror. William procceded to encircle London, cutting the capital off from the rest of the country until the city had no choice, but to surrender. By the end of the year, he had entercd London. On Christmas Day, in conscious imitation of Charlemagne’s coronation as Empcror on Christmas Day, 800 A. D., he was crowned by the Archbishop of York.

After his victory and coronation, William swiftly consolidated his rule. He rewarded the Norman barons who had fought beside him by parceling out among them the lands formerly held by Englishmen, who had died in battle, or who afterwards rebelled against him. As the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle bitterly commented: “He gave away every man’s land.” Within twenty years of the Conquest, nine-tenths of the land of England had changed masters. By scattering the holdings of his new magnates all over the Enghsh countryside, he gave the lords wealth, but retained the essential power in his own hands. Thus by adroit policy, he established the strongest and most stable monarchy in Europe.

The Conqueror’s system of land tenure was strictly feudal. The king himself remained the overlord and landlord of all England, so that even the greatest nobles were his tenants. Starting afresh in a new country, William was able to organize the feudal hierarchy, on more logical principles than existed in Normandy, where the land tenure and political and social organization had resulted from haphazard growth. England had been moving toward the development of a feudal society before the Conquest; the general principle of ‘”no man without his lord” was well-established. However, the full development of feudalism, with all it implied, awaited the arrival of the Conqueror and his redistribution of land.

One ironic incidental effect of Williams victory was the “return” to England of the Bretons, descendants of families that had been driven across the Channel by the Anglo-Saxon invasion five hundred years before. There had been many Bretons in the Norman army and they were appropriately rewarded. Men like Alan the Red, Ralph of Gael and Judhael of Totnes received vast estates, especially in southwest England, where Gaelic was still spoken.

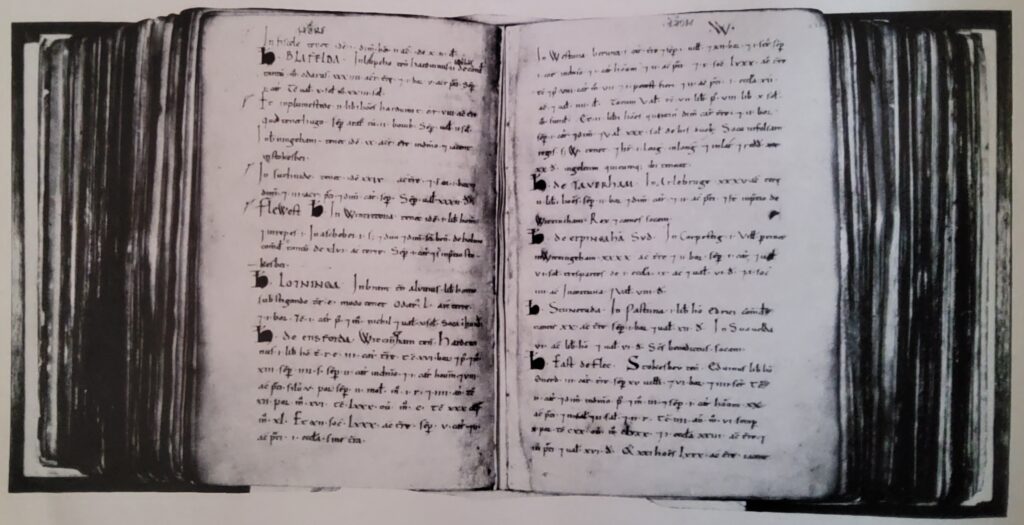

It is curious to find, at a later date, Bretons and Saxons uniting in rebelling against the Normans. For there were rebellions, especially among the Danes of northern England. William suppressed them with an iron hand: in his ‘‘harrying of the north” he almost wiped out the population in the Vale of York. Twenty years later, when he ordered virtually every cottage and hide of land in the country to be counted, so that the king could know and tax what he owned, the Vale of York was still deserted. That first great medieval survey, incidentally, was so thorough that it was compared to the Day of Judgment; the record came to be known as the Domesday (i.e. Doomsday) Book. The census caused much discontent and local revolts. William and his successors nevertheless succeeded in winning the confidence of their subjects — so much so, that William’s son, William Rufus, found he could depend on English levies to defend him against his own Norman barons.

William had come into England with the papal blessing, carrying a papal banner and wearing around his neck at Hastings the holy relics on which Harold had allegedly sworn fealty to him. Once in control of England, he proceeded to introduce into the English Church, the principles of Gregorian reform. He attempted to improve the education of the clergy and to enforce the celibacy of priests. Guided by the great churchman Lanfranc, whom he appointed Archbishop of Canterbury, he furthered the internationalization of the English Church, replacing English bishops and abbots by learned Frenchmen and Italians. He separated secular and ecclesiastical courts in order to assure the immunitv of the clergy from secular interference — a step that was to have far-reaching and often unpleasant consequences for his successors: William agreed 10 the payment of “Peter’s Pence” to the papacy, but at the same time, he strongly rebuffed the efforts of Gregory VII, to assert feudal authority Over the Crown of England and he saw to it that control of the English Church remained firmly vested in him alone. Anpeals to Rome, or the entry of papal legates into England, were forbidden without his — consent; and he resisted all the Pope’s efforts to interfere with his prerogative of appointing high prelates of the Church. His firmness gave England a privileged position which his successors maintained. Due to his policy, the full fury of the Investiture conflict that racked Central Europe never burst upon England. A life-and-death struggle between the English Church and the monarchy was delayed for a century. When it came at last, it culminated in the shocking murder of Archbishop Thomas Becket; but the monarchy emerged from that contest with its hold over the English Church basically strong.

The Norman Heritage in England

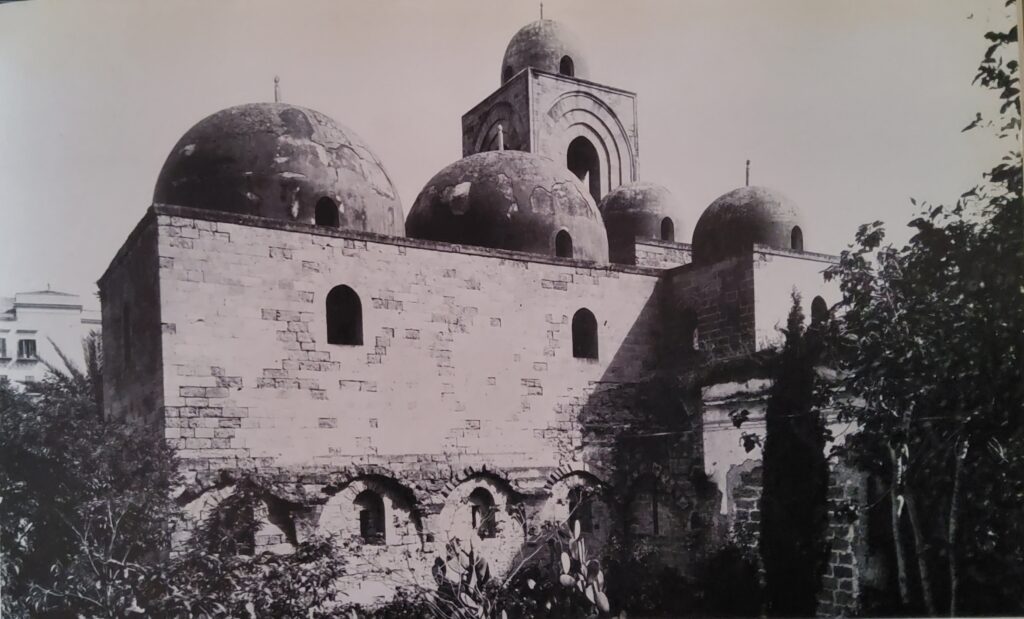

In one sense, the Norman Conquest can be considered the crowning accomplishment of that great wave of expansion which carried the sea-rovers of the Scandinavian world to Iceland, Greenland and even the shores of America, enabling them to found the Russian monarchy and guard the gates of Constantinople for the emperors. For Normandy had, after all, been a Scandinavian settlement and in the boyhood of William the Conqueror Old Norse was still spoken at Bayeux. However, the majority of the Northmen settlers in Normandy had adopted the language and the Latin civilization of their surroundings. What they brought to England, as well as to their far-flung settlements in Sicily and the Holy Land, was French speech and Roman traditions in government, law and church affairs, along with Viking energy and a new organizational talent that seems to have sprung from the amalgam. These descendants of Viking pirates actually put an end to what may be called the Scandinavian period in English history.

Until 1042, a Dane had been King of England; after 1066, England became too strongly centralized a monarchy for further incursions from the north to be possible. Moreover, the union of Normandy and England under one monarch, although it was not destined to last, brought England fully into the orbit of the European world. English history remained, after the Norman Conquest, a process of alternating approach to and withdrawal from the Continent — a process that has continued to the present day. While Scandinavia withdrew for centuries from the main arena of European politics, the English played their part, at first through their Continental possessions, later through Continental dynastic and political alliances.

In the first century after the Conquest, language remained one of the strongest links. Although the Norman nobility rapidly learned the Anglo-Saxon language, which after all, closely resembled the language spoken by their own grandfathers — they continued using French at court. Literature, which was always directed toward the literate leisure class, ceased to be written in Anglo-Saxon. The AngloSaxon Chronicle continued to be kept for ninety years after the Conquest, but it ceased with the accession of Henry II.

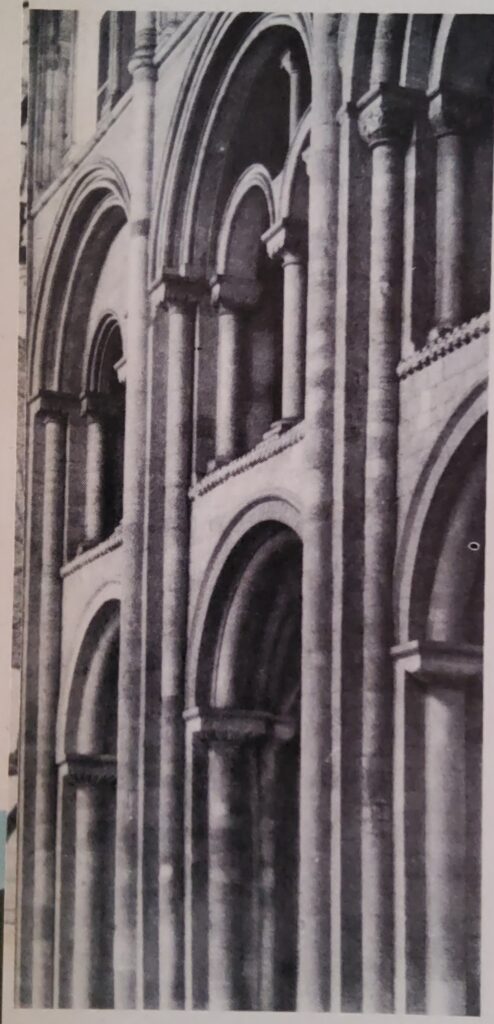

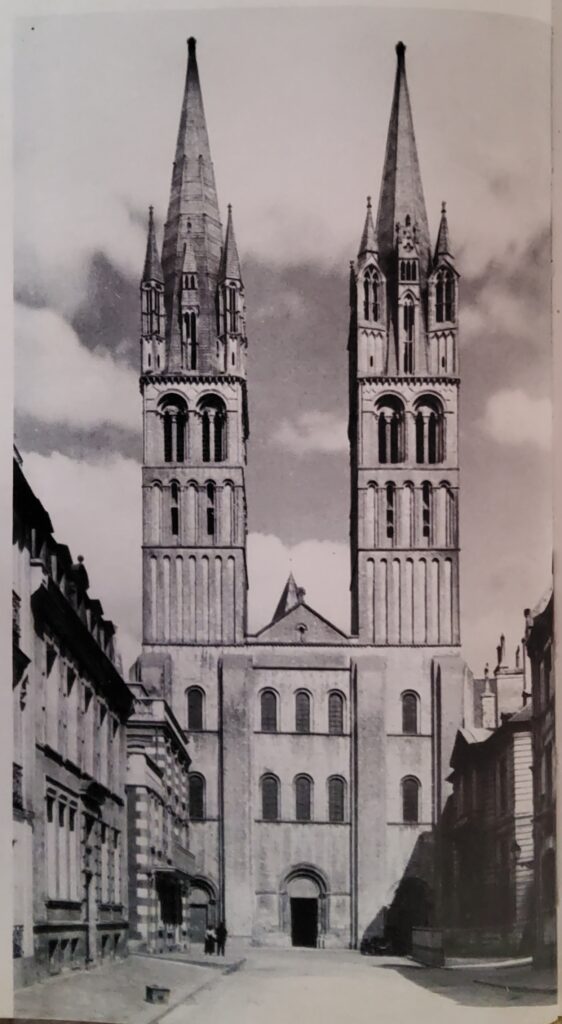

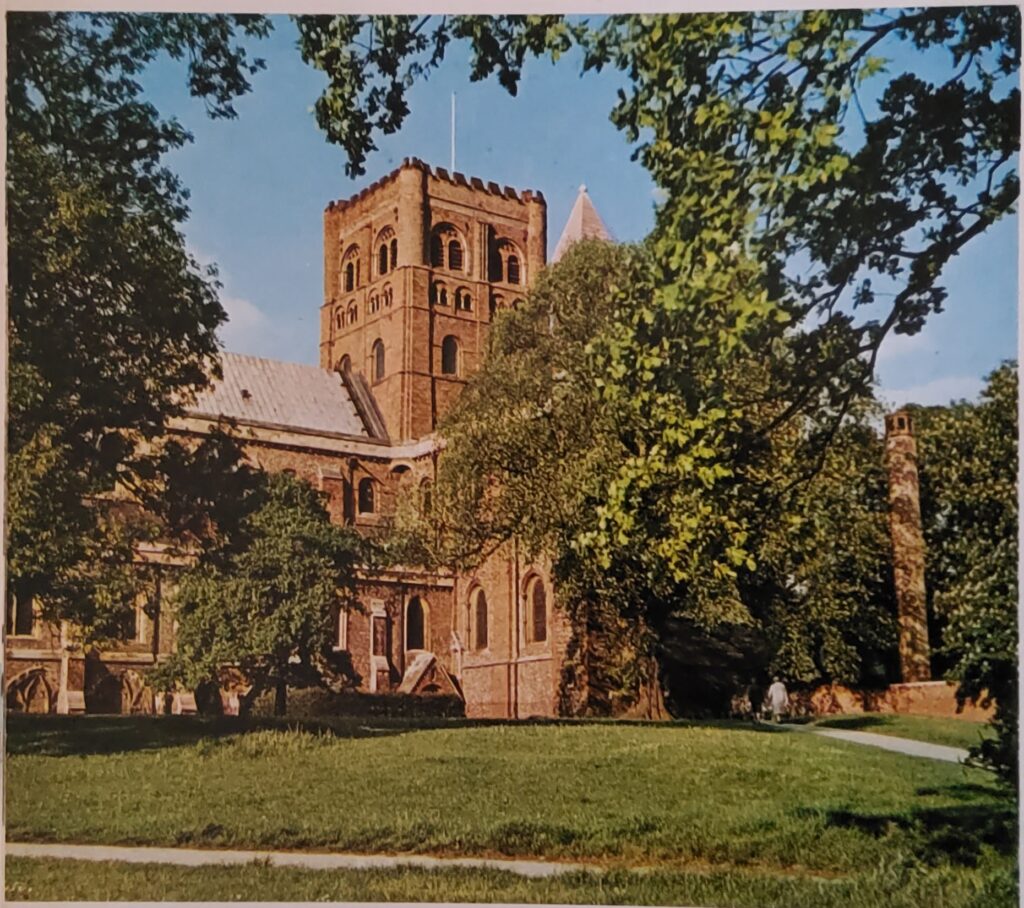

On the other hand, there was a remarkable outburst of literary creativity in the twelfth century, the consequence of growing wealth and a stabler society. In architecture, too, there was an enormous outburst of vitality; Canterbury, Lincoln, Wells and Salisbury cathedrals, to name just a few, remain witnesses to the Norman style. The generosity of William and his successors also resulted in the building of many monasteries throughout England, and led to a revival of monasticism. The monks reclaimed and cultivated many of the fens and forests of England, thereby adding materially to the wealth of the country. They contributed to the reform of religious life, and often brought from their motherhouses in France the learning of the Continent.

Altogether it can be stated — at the risk of all such generalizations — that the Norman Conquest, though it caused much suffering, also brought fresh air and an infusion of new energy into a somewhat stagnant society. It reorientated England into the mainstream of European history. As it turned out, William the Conqueror’s successors enlarged his Continental domains so greatly, that they nearly succeeded in swallowing all of France. The struggle of the kings of France to right the balance of power, influenced much of the subsequent history of Western Europe.