In the time when savage warriors roamed the plains and mountains of Italy, there stood on six low hills, just south of the river Tiber, six clusters of round huts made of twigs and leaves stuck together with mud. Each was a little town, the home of barbarian tribesmen. They herded cattle on the plain below, chased the wild pigs in the woods and tried to make things grow in their marshy fields. Although the towns were always fighting or stealing cattle and sheep from each other, they shared a market place in a clearing beside the river. They also shared a crude fortress of heaped-up earth and rocks on a seventh hill. The huts on the hills, the market place, the fortress – this, about B. C. 900, a hundred years or so before the Etruscans came to Italy, was Rome.

Then a powerful chief came to the place of the seven hills. When he had built a great hut of his own, on the widest of them, he called together the chiefs of the six towns. He told them that he planned to build a city on their hills and that their towns would all be parts of it. Whether the old chiefs agreed to the plan or not, it was done.

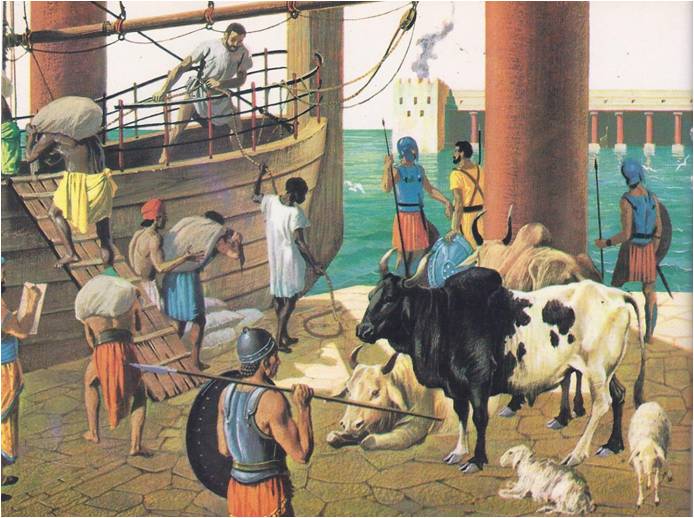

On the day in April which was the feast day of Pales, the guardian god of herds and flocks, the new chief performed the solemn ritual of the founding of his city. With a bronze plow, drawn by a caw and a bull yoked together, he dug one furrow – a sacred line that marked the city’s boundaries, the place where its walls would be built. He traced the lines of two main streets – one running north and south, one east-and-west and crossing in the market place beside the River Tiber. Then, on the Capitol, the tallest of the seven hills, he dedicated new huts as homes for Jupiter and Juno and Minerva, the gods whose protection he begged for the new city.

Romulus and Remus

No one knows where the great chief came from, or when he plowed his sacred line around the city. The people of five of the old villages were Latins. They were members of the tribe which claimed all of the broad plain, Latium, south of the Tiber River. The sixth village belonged to men from another tribe, the Sabines. The gods of the new city had Etruscan names, so perhaps the new chief was an Etruscan king.

The Romans told a story that answered all of the questions. It began in a little town called Alba Longa, a place where the Latins once had a temple to their old gods. There, the Romans said, twin boys were born – Romulus and Remus. They were not ordinary children. Their mother was a descendant of Aeneas and their father was the god Mars. For the king at Alba that made them dangerous. He was afraid that when these children of a god grew up, they would be strong enough to steal his throne just as he himself had stolen it from the children’s grandfather. The king ordered his servants to kidnap the babies and to leave them on the bank of the Tiber to die. The servants did as they commanded, but Romulus and Remus did not die. They were discovered by a she-wolf, who carried them to a field and mothered them like her own cubs until a shepherd found them and took them home to his wife.

Grown to manhood, the twins were everything the king had feared they might be: as fierce as the wolf who had mothered them, as noble as their ancestors Aeneas and almost as strong as their father, Mars. They killed the wicked king. Then they left Alba Longa and went back to the field where they had lived with the wolf, to build a city of their own. As they began to plan its walls, they argued. Each had his own design for the city and each wanted his own way. They tried to settle things peacefully by asking the gods to send a sign that would show which of them was right. When Remus prayed for the gods to vote for him, six eagles suddenly appeared in the sky, circled above their heads and flew away. When Romulus prayed, twelve eagles appeared.

“You see the sign of the gods!” Romulus shouted. “If I am king, our city will stand for twelve hundred years but if you are king, it will last only half as long.”

Remus refused to accept the eagles as signs. Furious, he tried to murder his brother, but was killed himself. So it was Romulus alone who marked out the boundaries of Rome with the sacred bronze plow. He did it according to the tale, on April 21, the feast day of the god Pales, in 753 B. C.

Growth of the City of Romulus

That was the story. April 21 was always celebrated as the birthday of the city and the wolf became its symbol, an animal sacred to Mars. For nearly eight hundred years a crude round hut, which people called the “House of Romulus,” stood among the shining white buildings that were built on the Palatine Hill. All that anyone knew for certain was that once there were six villages, but by 600 B. C. there was a thriving city. It was ruled by kings, until the last of them, an Etruscan, was driven out by the Romans in 509 B. C.

What happened during the four hundred years between remained a mystery, but the changes brought by those years were plain enough. By 509 B. C., the soggy fields had been drained and planted with vegetables, fig trees, olives and grapevines. There were more sheep and fatter cattle. A strong new fortress had been built, as well as a handsome temple on the hill called the Capitol.

All this looked like the work of Etruscans. The city’s people were not Etruscans, except, perhaps, for a few colonists who stayed behind when the king was driven away. Most of the people were Latins from the old villages and Sabines; some were wanderers who had drifted into the city and stayed. What they had been did not matter. Now they lived in Rome, they were all Romans. They were different from any people the world had known before – proud, strong, courageous and practical. These Romans were men who looked at life as a series of jobs to be done: a field to be planted, a house to be built, a family to be raised, a country to be conquered. The bigger jobs simply took more effort.

The Life of a Roman in Romulus

One such Roman was Publius Tullius Servius. His story was in his name: Publius, his own name, the one his friends used; Tullius, the name of his clan, the tribe of his ancestors; and Servius, his family name, the name of his father and of his father’s father. It was good to have such a name, for it proved that Publius came from an ancient, respected family. It reminded everyone he met of the famous deeds of his parents and grandparents. Rome was old-fashioned about such things and people honoured most the men whose ancestral histories were the longest. In politics, business, or society, nothing mattered more than a man’s family.

Publius and his own family lived in a one-room house built of clay bricks. Though they were far from poor, the room served them as a living room, bedroom, kitchen and dining room. Romans did not go in for luxuries. At mealtimes, the family gathered around the table set next to the hearth, which was in the centre of the floor. Their dinner was simple – wheal or oatmeal cakes, vegetables, a glass of wine and fruit. Meat was for special occasions only. What they had, they shared with the gods. Little clay statues of the Penates, the friendly spirits who looked after the food cupboard, were placed on the table so that they could feel that they were a part of the family. Bits of food and some wine were dropped into the fire as offerings to the goddess Vesta, who protected the hearth and all the household.

Vesta and Janus, the gatekeeper who guarded the door, were the most important of the family gods, but there were dozens of others. They were not the adventurous gods the Greeks had known, but practical minded, like the Romans who worshipped them. Each had his job to do and his price for getting it done – a sacrificed animal, or an offering of honey, cheese or milk. When Publius went out to his fields in the spring, he prayed to Terminus, the god who looked after the boundaries of the farm and then to Seia, who watched the corn seed in the ground. As summer began and the corn grew tall, Publius prayed to Flora, because it was her job to take care of the flowering corn. When the ears of corn were ripe, he returned to Runcina, who watched over the harvesting and finally to Tutilina, who kept it safe in the barn.

There were many more of these useful gods and with each of them Publius made a bargain. He promised to make a certain offering in return for a job well done, but he did not give it until after the job had been performed. If something went wrong, he did not pay the god at all. That was common sense, Roman sense.

Publius and his fellow Romans treated the gods of the city, great and small, in nearly the same way. They looked to Janus to guard its gate and had built him a temple, like a huge gateway in the Forum, the old market place. Its great doors, the “Gates of War”, were left open in times of war; when there was peace, they were closed. Nearby was the temple of Vesta, with the sacred hearth of the city. A group of priestesses, the Vestal Virgins, tended the fire that was never allowed to go out.

On the Capitol Hill stood the great temple of the three gods who had been Rome’s protectors since the day of its founding – Jupiter, the sky king; Minerva, the goddess of wisdom and art; and Juno, whose special care was for women and babies. Vulcanus, the rumbling god of earthquakes and volcanoes, had his own temple. Publius was not slow to make his offerings there. Publius was not slow to make his offerings there. Like every Roman, he paid what was due and added strong prayers, for Vulcanus was already too busy in Italy. A field outside the city wall, the Campus Maritus, where the soldiers marched and practiced battle maneuvers, was dedicated to the special Roman god, Mars. He was worshipped as the god of planting as well as the god of war. That, too, was good sense – in the ancient world both activities usually got started in his month, March.

The Duties of a Father

Among all these gods of Publius’ city, there was not one whose job it was to tell the Romans how to behave. That was the duty of their fathers. As the father of a Roman family – the pater familias – Publius Tullius Servius was a king in his home. He had the power of life and death over his wife, his children and his slaves. Their behavior was his responsibility. He owed it to his ancestors and Rome to teach them to act honestly, nobly and bravely and to punish them if they did not. The Romans told many stories about fathers who had killed their own sons for cowardice or disobedience.

Like most of the men he knew, Publius tried to be as fair as he was strict. When there were serious problems, he discussed them with his family before he decided what to do. The law said that his wife was his property, like his house, his cattle, or his slaves, but he treated her as his partner. His house was hers to manage and their children hers to love. Like all Romans, they wore only clothes made in their own household and Publius’ wife saw to the making of them. She was free to go about the city as she liked and Publius never asked her, as Greek husbands did, to stay out of sight when his friends came to dinner. His feelings for his wife were like those of another, who carved these words on his wife’s gravestone:

Stranger, what I have to say is short, so stay and read. Here is the unbeautiful grave of a beautiful woman. Her parents named her Claudia. She loved her husband with her whole heart. She bore him two sons: one she left alive on the earth, the other she buried in the earth. Her speech was gay but her bearing seemly. She kept the home. She made the wool. I have spoken. Now go.

Publius’ most important job was the education of his sons. They had no school and no tutor but their father. He taught them the sports that would make them strong – running, swimming, boxing and wrestling. As soon as they could wield sticks and little wooden daggers, he began to teach them war games, too, for every Roman citizen had to serve in the army. He told them about their ancestors and the wax masks of their faces which hung on the walls of the house to show that they were still honoured members of the family. On holidays, the masks were taken down and carried to the celebrations. They were taken to every important family ceremony, for the Romans had the old Etruscan fear of the spirits of the dead and they were careful not to insult an ancestor whose ghost might be hovering about.

A Practical Education

As Publius’ sons grew older, he took them with him when he went to his fields or about the city on business. In that way, they could learn by watching him. All of their training was practical and all of it was serious. Discipline was what made the difference between a Roman and any other man. “Obey the command,” Publius would say, “act as a Roman and die to save Rome, our family, or your own honour.” Nothing was studied because it was fun or just interesting. Philosophy and poetry were for the Greeks. The only stories Publius told his children were about the Roman gods and heroes.

He told them about Romulus, the sacred plow and the family of the Roman state. When Romulus built his city, Publius said, he chose the finest men to be his soldiers, the legions who marched behind the silver eagles mounted on standards. One hundred of these men, the best and the richest, he made his counselors. He called them senators and told them to look after the poorer and weaker men of the city. To the lesser men, Romulus also gave a duty: to love and honour his senators as fathers, the patrons of Rome.

When the Romans chased the Etruscan king from their city, the senators took charge of the government. They served so wisely that visitors from other countries called them “the council of kings.” Each year they elected two men as consuls, presidents of Rome, who managed the city and commanded the armies. As the city grew, other officers were elected. Four officials called quaestors, for example, assisted the consuls. Censors kept track of the people by taking a “census” and “censored” their conduct by punishing them when they misbehaved or broke the laws.

Over the years, the senators and officials became the aristocrats of Rome. They owned much of its land, made the laws and many of them began to look with contempt at the noisy “children” they were supposed to look after. The other citizens in turn, began to complain about “city fathers” who told them what to do but never consulted them. Then the people went on strike. One morning they simply walked out of the city. They refused to come back unless the senate agreed to treat them like men and with proper respect.

The strike not only left Rome empty, but without an army. The senators rushed to make an offer that would bring the citizens back. They would let an assembly of people vote about some of the city’s business, they said. The assembly would elect tribunes, who would have the power to veto anything done by any other official, even the consuls. A committee was appointed to write down the laws of Rome and to set them out on bronze tablets in the Forum, where everyone could see them and know his rights as a citizen.

The Rise of the Republic

The people accepted the senators’ offers and returned to the city. They called two or three more strikes before things were settled to their satisfaction, but out of the arguments and the political deals grew the Roman Republic, the new family of citizens. Its rules were the laws of the Twelve Tablets, posted in the Forum. Its strength was in the old Roman virtues which every father was expected to teach his sons: honour, good sense and the courage to get on with a job no matter how difficult or dangerous it was. The job of running the city was still divided between the city fathers in the senate and the commoners in the assembly, but they tried to work together. So long as they did, the Republic and Rome were strong.

These were the lessons Publius taught his sons, for he had served as a consul and was now a senator. He hoped that his sons, too, would someday serve as city officers. Rome needed good leaders; it was growing more powerful every day and many other cities looked to it for leadership. All of the Latin tribes of Latium had allied themselves to Rome. In 493 B. C. they signed a contract of friendship:

Let there be peace between the Romans and all the Latin cities so long as heaven and earth are still in the same place. Let them never make war on each other, but help each other with all their force when attacked and let each have an equal share of all the spoil and booty won in wars they fought together.

Now other towns in Italy were making contracts with Rome, for they shared many dangers. In his youth, Publius had lived through the awful years when fierce, barbaric Gauls had swept down from the Po Valley in the north. In 390 B. C., they had taken Etruria and invaded Rome itself. All of the city had been captured except the citadel on the Palatine Hill. That ancient fortress had never fallen, finally the Gauls had given up trying to take it. They did not leave Rome until the citizens had suffered the shame of buying back their own city with a ransom of gold.

Publius and his friends in the senate swore that such a thing would never happen again. They had a great new wall set up around Rome and added thousands of men to the army. Publius said that if his sons served their city and its legions as true Romans should, then his sons’ sons would see Rome conquer the whole of Italy.

Rome Conquers New Lands

As it turned out, Publius proved to be right. The Gauls, who had taken Rome’s gold and gone away, were the last barbarians to invade the city for eight hundred years. About 350 B. C., the Samnites, the savage tribesmen who held the mountains that ran south along the peninsula, attacked their kinsmen in the lowlands and threatened Rome. The legions marched out of the city, chased the invaders back to the hills and won for Rome the great plain of Campania with its wealthy city, Capua. Then the Latins, afraid of Rome’s new strength, tried to break the old contract of friendship. When they went to war about it, Roman armies swept down on their little towns, forcing them to agree to fight beside the Romans instead of against them.

That was in 353 B. C. In the same year, Philip of Macedon, the father of Alexander the Great, conquered the city-states of mainland Greece. While he and his son dreamed of building an empire in the East, the practical Romans were laying the foundations for an empire that would spread in every direction.

It began with cities and with roads. The Latin towns had a special place in the Roman plan. Their people were Rome’s closest allies and had “Latin Rights” which gave them some of the privileges of Roman citizens. There were colonies too, because wherever the legions went, Roman settlers followed. Dozens of new towns sprang up at river crossings and ports and on the hills that commanded the richest fields in Italy. In times of peace, they added to Rome’s wealth; in times of war, they were headquarters for the armies. Their people were full citizens of the Republic. There was another sort of arrangement for the old Italian towns which agreed – or were forced – to make contracts with Rome. The Italians fought for Rome, but kept their own governments and officials. They could become citizens of Rome only by moving to the city itself.

For over a century, the Gates of War stood open in the Forum and the list of towns tied to Rome grew longer and longer. With so many places to look after, the Romans needed a way to move their troops quickly. In 312 B. C., the senator Appius Claudius Caecus began to build a highway between Rome and Capua. It was called the Appian Way and was the first of the great Roman roads. It was straight, level, weatherproof and built to last almost forever. On a foundation of stones, the Roman engineers poured crushed rocks, bound them together with a thick layer of cement, then covered it all with smooth paving stones so carefully fitted together that water could not seep between them. The Appian Way crossed the rivers on great stone bridges. A viaduct carried it over the Pontine Marshes. No one in the world had built such roads before and not until the coming of the railways did anyone find a better method of moving men and goods by land. When the Appian Way was finished, the Romans planned a network of highways – to Brundisium and the seaports in the south, to the ancient cities in Etruria and north as far as Arminium on the coast of the Adriatic.

Meanwhile, as the roads and armies moved down the peninsula, the Greeks in the southern cities became frightened. They wanted no “contracts” with anyone, especially Rome, but they knew the strength of the legions. In 280 B. C., the Greek cities hired an army of 20,000 men from the Peloponnesus to defend them and asked Pyrrhus, the most famous Greek general of the time, to take command.

The Defeat of Pyrrhus

Pyrrhus was another man who dreamed of winning an empire. His followers called him the “Eagle”. When he sailed to southern Italy to fight the Romans, he was certain he was taking the first step toward setting up a western empire. The twenty elephants he brought with him were meant to remind his enemies that he was a sharp, up-to-date commander from the East, like Alexander. After all, he said, the Romans were only barbarians.

The Eagle met the Roman legions on the battlefield, defeated them and offered them peace. To his great surprise, Rome refused and raised another army. Pyrrhus defeated it, too, but his casualties were high. “Another such victory,” he said, “and we were lost.” So he left Italy to try his luck against Rome’s allies, the Carthaginians, in Sicily.

In 275 B. C., he was back. Rome had raised a third army and this time Pyrrhus’ clever strategy could not overcome the dogged courage of the soldiers he called the barbarians. The Roman wolf broke the Eagle’s wings and Pyrrhus gave up the fight. As he limped away from the Italian plain where his dreams of empire had been ruined, he thought of the great new powers he had seen in the West. Rome was only one of them; perhaps it was the strongest. Pyrrhus sighed. “What a glorious battlefield I leave to Carthage and Rome,” he said and took his elephants home to the Peloponnesus.

One by one, the cities surrendered. By 256 B. C., Rome controlled them all. The new roads were extended to Cumae, Neapolis, Sybaris and the rest; Romans began to say, “All roads lead to Rome”. This was certainly true of Italy, for the Romans had conquered the entire peninsula. In Rome itself, the Gates of War were still not closed. Many kings and cities were jealous of Rome’s power. None of them was more anxious to do something about it than Carthage. New wars were brewing and Pyrrhus’ prophecy about the battlefields of Italy would soon come true.