Zealots, for sixty years or more, had formed the “resistance’’ against the Romans in Judaea and their ideas were shared by many other Jews who were not active members of their party.

After the death of King Agrippa in A.D. 44, Judaea returned to direct Roman rule and from that moment Jewish history seemed to take on an air of inevitability. According to orthodox Jewish belief the Holy Land belonged to God and God alone. The presence of a Roman Governor in Jerusalem was in itself an affront to God and to pay tribute to the Emperor was to give to a non-believer what was God’s by right. Tension and disorder steadily increased, stimulated by Roman maladministration, Messianic excitement and nationalist activity. The fatal explosion finally came in A.D. 66. With the resulting loss of their land and the Temple at Jerusalem, the Jews’ religion ceased to be a religion that demanded the ritual of sacrifice and the people themselves were scattered abroad without a national home until the present century.

In the summer of the year 66 the priests of the great Temple of Yahweh in Jerusalem refused to offer their customary daily sacrifices for the well-being of the Roman Emperor and people. These sacrifices were an accepted token of Israel’s loyalty to Rome and a refusal to continue making them was tantamount to a declaration of revolt. The priests concerned were members of the lower order of the Temple clergy, who subscribed to Zealotism.

Behind this refusal of the lower priests lay a complex situation. The higher clergy, who formed a priestly aristocracy, were presided over by the High Priest. This aristocracy supported the Roman government of Judaea because it ensured their own social and economic position; the maintenance of the “loyal” sacrifices was essential to good relations with the Romans, but the policy and attitude of these priestly aristocrats made them unpopular with the people and particularly with the lower clergy, who longed for the freedom of Israel. To control the members of the lower clergy, the High Priest had reduced or cut off their stipends. The fateful refusal to offer the sacrifices, however, was only taken when Eleazar, a young aristocrat and captain of the Temple, defected to the lower clergy. Eleazar’s defection provided the malcontents with an able and vigorous leader and it was he who persuaded them to revolt.

Fighting quickly broke out in Jerusalem. The High Priest and his party, reinforced by troops sent by the Jewish prince Agrippa II, sought to gain control of the Temple. They were fiercely opposed by the lower priests, who were joined by the Sicarii, the extreme action group of the Zealots. Meanwhile, Menahem, the surviving son of Judas of Galilee and now leader of the Zealots, had suddenly attacked and destroyed the Roman garrison at Masada, the great fortress by the Dead Sea. Equipping his followers from the armory there, Menahem quickly made his way to Jerusalem and at once took charge of the revolt. The forces of the High Priest and Agrippa were soon defeated and many of the priestly aristocrats were murdered.

Menahem seems to have assumed royal powers, probably as the Messiah-King, but his reign was short. Eleazar, doubtless jealous of the new leader who had assumed command of the revolt that he had started, plotted to have him murdered in the Temple. Some of Menahem’s followers, including a relative named Eleazar ben Jair, managed to escape the ensuing massacre and withdraw to Masada.

The death of Menahem left the revolt leaderless. He had been dynastic head of the Zealot movement and had been at once accepted as the charismatic leader of Israel’s revolt against Rome. None of the other leaders of Zealot bands or rebel groups had the prestige or authority needed to command a national revolt. However, the Jews were committed to rebellion and they continued to wipe out surviving Roman garrisons in Jerusalem and elsewhere. In retaliation the Gentile inhabitants of Caesarea, the Roman headquarters, rose against the Jews and slaughtered twenty thousand of them, according to the Jewish historian Josephus. This massacre provoked Jewish reprisals against many Gentile cities in Palestine and in Gaulanitis, east of the Sea of Galilee. In turn, Jews living as far afield as Syria and Egypt had to pay the penalty for their compatriots’ actions.

The procurator of Judaea, Florus, seems to have done nothing effective to maintain Roman authority during the initial stages of the revolt. Josephus claims that Florus actually welcomed the revolt as an opportunity to cover up his own maladministration, which had far exceeded that of any previous governor. Whether or not that was the reason for Florus’ initial inaction, the situation in Judaea rapidly grew beyond his military resources to cope with it. It was now the duty of the legate of Syria, Florus’ superior in the administration of the Roman Empire, to intervene and restore Roman sovereignty.

The Syrian legate, Cestius Gallus, took some three months to assemble his forces for the punitive expedition. His army consisted of one full-strength legion, the twelfth, with other specially selected legionary reinforcements, six cohorts of other infantry, four squadrons of cavalry and some fourteen thousand auxiliary troops. It was a formidable force, well calculated to deal with the disorganized and untrained Jewish rebels.

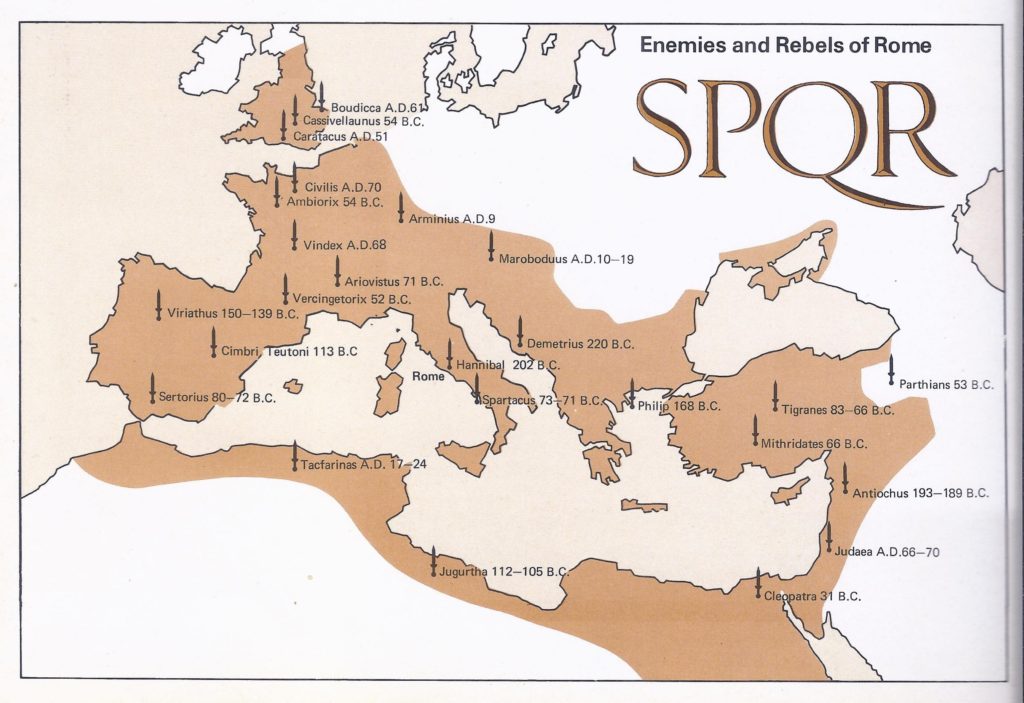

Judaea against the might of Rome

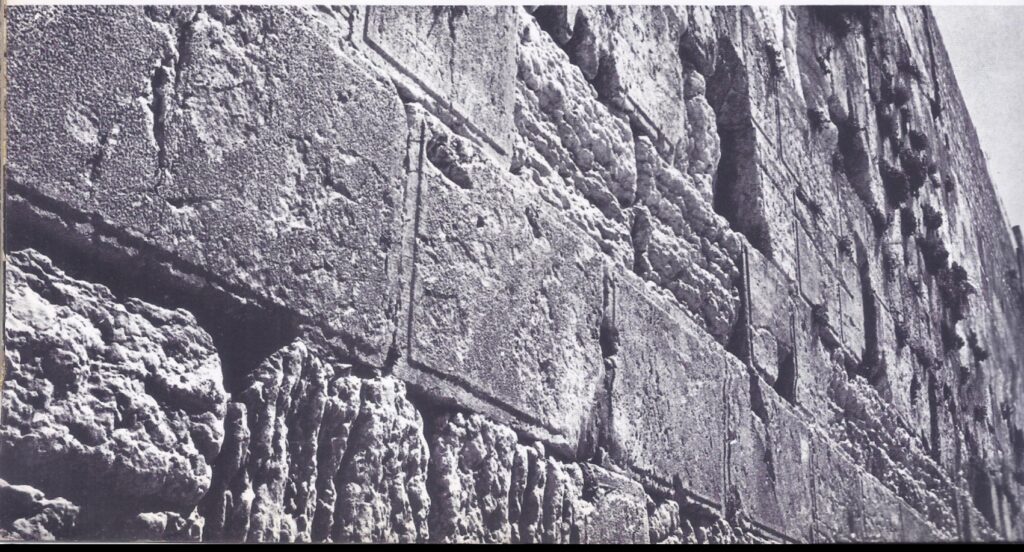

Entering the country from the north, the Roman army swept aside whatever opposition the rebels had managed to organize in the countryside and laid siege to Jerusalem itself. They soon penetrated the city’s fortifications and made preparations for the final assault on the Temple walls. Occupying a commanding position superbly reinforced by massive walls, the Temple constituted the keypoint in the defense of Jerusalem. It was, moreover, the most sacred spot in the Holy Land, and all Jews could be expected to fight fanatically in its defense.

The Jews did, indeed, fight with fanatical courage, but they were no match for Roman military science and professional discipline. They were actually beginning to despair of the outcome of the contest, when Cestius Gallus suddenly and unaccountably ordered the operation to stop and withdrew his troops to neighboring Mount Scopus. The next day the Jews saw the Roman army retiring northwards, evidently breaking off the siege. At first they feared a ruse, but when they realized that the Romans were indeed retreating, their joy and exultation knew no bounds—here truly was proof of the succor of Yahweh, their god. In his honor they had challenged the might of Imperial Rome, and, at the eleventh hour, he had miraculously intervened and put their dreaded foe to flight. The Jews quickly pursued the retreating Romans and caught them as they descended the narrow Beth-horon pass. Only by sacrificing his rearguard and abandoning his heavy equipment was Cestius Gallus able to extricate his forces and struggle back to safety in Syria.

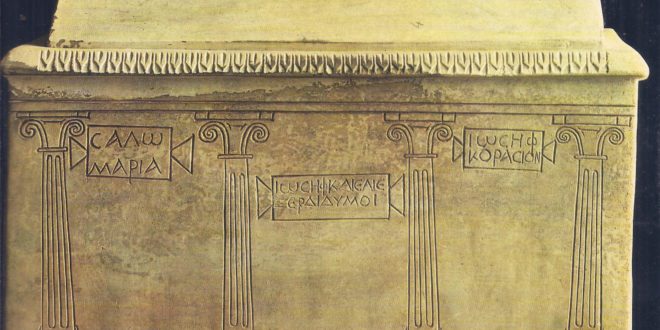

Thus ended the first armed encounter between puny Israel and mighty Rome. The Jewish rebels had trusted to their god and not to their military resources; matched with Rome, their cause was hopeless. But they had won, defeating a legionary army. The very site of their victory, the Beth-horon pass, was portentous—there Joshua had defeated the Amorites, and Judas Maccabaeus had triumphed over the Seleucid army under Seron. Yahweh was the god of battles: he had given victory to their ancestors fighting against enormous odds, and so had he given victory to them. In the face of what appeared to be such a marvelous demonstration of divine approbation, even the cautious and hesitant were won over to a wholehearted commitment to this struggle for Israel’s freedom. Coins were specially struck, expressive of their exultation and faith. They bore inscriptions: “Jerusalem the Holy”; “Deliverance of Zion”, “Redemption of Zion.”

The defeat of Cestius Gallus was a serious blow to the Romans, both to their prestige and to their imperial ambitions. Judaea was a vital link in the defense of their Near Eastern provinces and Egypt. There was, moreover, a large Jewish population in Mesopotamia that might rise in sympathy. Rome’s traditional enemies, the Parthians too, were always ready to invade at a sign of Roman weakness. The Emperors Nero, whatever his other failings, made a wise choice of commander to restore Rome’s dominion over rebel Judaea. He appointed Vespasian, a veteran who had proved his ability in hard campaigning in southwestern Britain. No chances could be taken next time and Vespasian set about preparing a powerful army of three legions and a strong auxiliary force.

The exact situation in Jerusalem at this time is difficult to determine, because of the historian Josephus’ apologetic concern about his own dubious part in the events that he describes. He is our chief source of information, but he is often elusive and obscure about matters in which he was personally involved. From the accounts, sometimes conflicting, in his Jewish War and in his Autobiography, it would seem that a moderate party endeavored to gain control in Jerusalem and coordinate the nation’s forces for the greater struggle with Rome that was sure to come. Josephus claims that he was appointed general in Galilee, to fortify its cities against a probable Roman advance from Syria, and he tells how assiduous and ingenious he was in carrying out his task. He also discourses at length on the iniquities of various rebel bands, and particularly on one of the Zealot leaders, John of Gischala. But, as the sequel suggests, there was undoubtedly another side of the story, and it is probable that John already suspected Josephus’ loyalty to the Jewish cause.

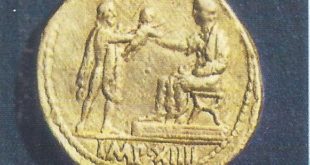

(1) Bronze coin of Agrippa A.D.50-100

(2) Shekel of Bar-Kokhba, A.D. 133

(3) Antioch assertion of Tiberius, A.D. 14-37

(4) Bronze coin of Herod the Great, 37-4 B.C.

(5) Shekel of the first Jewish revolt A.D. 66-70.

(6) Deleption of Mattathias Antigonus 40-37 B.C.)

Rome Imposes Her Presence

By the spring of 67 Vespasian was ready to begin his campaign, but the new Roman commander was confronted with a very different situation from that which had faced Cestius Gallus the previous autumn. His route to the insurgent capital was now blocked by a number of fortified towns, which had first to be reduced before he could venture into the barren hills of Judaea for the final siege of Jerusalem. This was a difficult, protracted task, for it meant a succession of sieges of strongly held places. Unable to oppose the Roman legionaries successfully in the open field, the Jews nevertheless excelled at fighting among fortifications; in such operations their fanatical courage and individual resourcefulness matched the discipline and military science of the Romans. However, it was a mode of warfare that took a terrible toll of life: not only was the defeated garrison eventually wiped out, but the inhabitants were generally massacred by the Romans, exasperated by long resistance and their own heavy losses.

During the campaign of 67, Vespasian captured a number of Judaean towns. Josephus gives a long account of the siege of one of them, Jotapata. where he was the Jewish commander. To escape death after the final assault on the town, Josephus surrendered to the Romans. Brought before Vespasian, he assumed the role of prophet and foretold that Vespasian would become Emperor of Rome. Whether Vespasian believed this audacious prophecy, we have no means of knowing other than from Josephus’ own account, but he kept Josephus a prisoner at his own headquarters instead of sending him to Rome as he had first intended. In 68 Nero died and from a resulting civil war Vespasian emerged in 69 as Emperor. Josephus fortune was made. He first served as a liaison-officer on the staff of Titus, Vespasian’s son and successor as commander in Judaea. After the successful siege of Jerusalem, Josephus returned to Rome with his imperial patrons and there he wrote his Jewish Wars to commemorate their victory over his own people.

The Roman reduction of Galilee seems to have resulted in an internecine struggle for leadership among the insurgents in Jerusalem. Josephus’ account of it was inspired by apologetic motives; but it would appear that the moderate party, led by Ananus, a former High Priest. gradually lost control as Zealot groups from Galilee congregated at Jerusalem. The arrival in Jerusalem of John of Gischala gave the Zealots a capable leader and supported by a strong body of Idumaean rebels, they finally overwhelmed the moderates and killed Ananus along with other leading figures. The Zealots now had complete control of the Temple and it is significant that they proceeded to elect a new High Priest by the ancient custom of drawing lots — doubtless an attempt to end the monopoly of the office long exercised by the priestly aristocracy. The Zealots also burned the public archives, containing the money-lender’s bonds, an action taken, according to Josephus, to encourage the poor to rise against the rich.

The Roman campaign of 68 was devoted to reducing insurgent centres outside Jerusalem. It was probably during the operations in the area of Jericho that the monastic settlement of Qumran was destroyed. The members of the community had anticipated the attack by hiding their sacred scriptures in adjacent caves, where they remained forgotten until their chance discovery in 1947 and their subsequent fame as the Dead Sea Scrolls.

When Vespasian was elected Emperor, the campaign of 68 ended. It became necessary for him to leave Palestine, with a considerable force, to make good his title at Rome. As fighting ceased, only the strongholds of Herodium, Masada and Machaerus — outside of Jerusalem itself — remained in Jewish hands.

The suspension of the war in Judaea during 60, however, was of little avail to the Jews. According to Josephus, fierce struggles for mastery still continued among the insurgents in Jerusalem. He charges the rebel leaders with terrible enormities, of which the chief victims were the people of Jerusalem. That his account is distorted by personal interests is certain; it paid him to blame the Zealots to cover up his own betrayal. Indeed, the theme of his Jewish War is that of a peaceable people being dragged to disaster by brigands and fanatical desperadoes—namely, the Zealots. He is silent or elusive about the religious ideals of the Zealots; for they clearly had a faith, however fanatical, which he lacked. Josephus was always too mindful of the reality of Roman power to share in the Zealots’ whole-hearted devotion to Yahweh.

In the spring of the year 70 the Romans were ready for their long-delayed vengeance on rebel Jerusalem. Vespasian appointed his elder son, Titus, to command the final operations. Titus assembled his army in Egypt and from there marched into Judaea at the head of the most powerful force yet directed against the Jews. There were four legions, including the twelfth, which was intent on avenging its defeat in 66 and they were supported by a large auxiliary force.

The End of a Nation

The approach of the Romans, shortly before the Passover, at once united the Jewish factions within the city. John of Gischala and the Zealots held the Temple; and Simon ben Gioras organized the defense of the rest of the city. Jerusalem had three separate strongholds: the Temple; the fortress of Antonia, adjacent to it; and the palace of Herod, defended by massive towers, in the Upper City. Surrounded and subdivided by walls, the city had to be taken piecemeal. From the east it was overlooked by the Mount of Olives; but the steep intervening valley of the Kedron rendered it virtually impregnable on that side. The northern side was its weakest, despite efforts made to strengthen the defenses. Accordingly, it was from the north, that Titus began his attack.

The subsequent siege, one of the most terrible in history, is vividly described by Josephus, who was present on the staff of Titus. From the start, the Jewish cause was hopeless. The city was crowded with refugees, as well as with troops and famine soon became a more terrible scourge, than the bombardment of the Roman ballistae. Josephus records a case of cannibalism — a mother killed her child and ate it. The Romans completely encircled the city with a wall of their own, built to prevent supplies from entering and refugees from escaping. Jerusalem was, indeed, “kept in on every side,”’ as Jesus is recorded to have prophesied.

The Romans gradually broke their way through the outer and inner walls of the city, but the Jewish patriots fiercely contested every advance towards the Temple, the focal point of their resistance. The fighting was extremely savage and prisoners were cruelly treated, by both sides. The reply made by John of Gischala to a Roman offer of surrender on terms, shows the spirit of the defenders. The Romans had waited until Jewish morale would be at its lowest; the last lamb had been offered in the Temple and now the daily sacrifice to Yahweh had to stop. The Zealot commander nevertheless replied firmly that “he never would fear [its] capture, since the city was God’s.”’

At last, on August 29, the legionaries broke into the Temple. Its courts were crowded with refugees, hoping to the last for a miracle of divine intervention and they were butchered by the ferocious legionaries. Accidentally, according to Josephus, the Temple was set ablaze by a Roman soldier who hurled a firebrand into an inner chamber. Despite the efforts of Titus to save the famous sanctuary, the legionaries could not be stopped in their lust for slaughter and destruction. Thousands of Jews perished in the Temple courts. Many priests retreated to the roofs, where they hurled ornamental spikes down on the Romans and finally plunged to their deaths in the flames of their burning sanctuary. When order was restored, the victorious legionaries erected their standards in the Temple courts and offered sacrifice to them. saluting Titus as Imperator. This act, was a strange fulfillment of the prophecy, the Jews had long feared, that the “Abomination of Desolation” would be set up in their Temple.

The capture of the Temple marked the virtual end of the revolt. Fierce fighting continued in the Upper City, but by September 26 all Jerusalem was in Roman hands. Most of the city had been reduced to a smoking ruin and Titus ordered what was left standing to be razed, except the three great towers of the palace of Herod, which he preserved as a monument to the former strength of Jerusalem. Jewish losses during the siege had been enormous — Josephus puts the number at 1,100,000. The figure is surely a gross exaggeration: but the true figure must have been very large, for the siege was long, the famine severe and the fighting fierce and at close quarters. The number of Jewish prisoners taken during the whole war is estimated by Josephus as 97,000, many of whom subsequently perished in the arenas of the Empire.

Titus returned to Rome. There, in 71, Vespasian and Titus celebrated their victory over rebel Judaea in an elaborately staged triumph. The victorious legionaries paraded through the streets of Rome with multitudes of Jewish prisoners displaying the rich booty, including the treasures of the Temple, followed by their proud commanders. The triumph culminated with the execution of Simon ben Gioras, as the chief rebel general and a sacrifice of thanksgiving to Jupiter Capitolinus for the victory. On the Arch of Titus, in the Forum, two bas-reliefs still commemorate this triumph — the legionaries exulting as they carry the great Menorah of the Temple, the silver trumpets and the altar of shew-bread, while a winged Victory crowns Titus.

Even after the fall of Jerusalem, the Zealots did not give up the struggle. Some escaped into Egypt, where they tried to stir the Alexandrian Jews to revolt. They were rounded up, tortured in an endeavor to make them acknowledge “Caesar as lord’’ and executed. At Masada, by the Dead Sea, the Zealot garrison under Eleazar ben Jair held out until A.D. 73, when the Roman commander Silva laid siege to the fortress with the tenth legion. By incredible feats of military engineering in that waterless desert terrain, the Romans surrounded the great rocky plateau with a wall, obviously intent on preventing any escape. They also built a great ramp, to bring their battering-rams within range of the fortress walls. But the Zealots fought back until they saw that further resistance was hopeless.

On the night before the final assault, the Jewish defenders killed their families and then themselves, preferring suicide to surrender. When the Romans broke in the next day, nine hundred and sixty dead bodies, among the smoking ruins of the fortress, testified to Zealot faith and fortitude.

The destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70 marked the definitive end of the Jewish national state until its rebirth in 1948. During the intervening nineteen centuries the Jews, scattered throughout the world, were a homeless and persecuted people. In 1967, in the Six Days’ War, they finally completed their return to their ancient home by gaining possession of the Temple site, but in the struggle to resurrect their national state, it has been to the Zealots of Masada that many have looked for inspiration. The excavation of that tragic site has been an act of national piety, which movingly links the new Israel with the old Israel that died there so heroically in A.D. 73.