Judea was destroyed and it’s people were scattered due to revolt in the East. Herod the Great died in the spring of 4 B.C.; his death sparked off an explosion of the long pent-up feelings of his Jewish subjects. Revolts immediately broke out in different parts of the country under various leaders. The situation was made worse by a Roman procurator, Sabinus, who moved in with troops to secure Herod’s very considerable property for the Emperor Augustus. At Jerusalem, crowded with pilgrims for the feast of the Passover, armed conflict soon broke out. The Romans were ordered to withdraw by the rebels, “and not to stand in the way of men who after a lapse of time were on the road to recovering their national independence.”

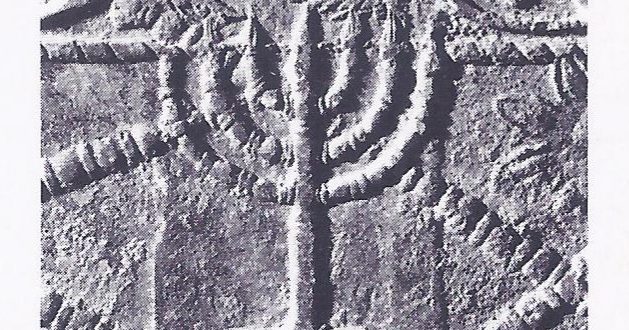

This statement of Jewish aims, which is recorded by the Jewish historian Josephus, is significant. It embodied an ideal, inspired by traditions of the heroic days of David and the Maccabees, which was rooted in the peculiar nature of Jewish religion. Every Jew was brought up to believe and the belief was reinforced daily by the study and practice of the Torah — that Yahweh, the god of Israel, had given his people the land of Canaan as their Holy Land, where they were faithfully to serve him. This belief implied a conception of the state as a theocracy; Yahweh owned it and was its sovereign lord, and his vice-regent on earth was the high priest. This conception in turn implied the freedom of the Jewish people to devote themselves to the maintenance of this theocracy.

Judaea under Roman rule

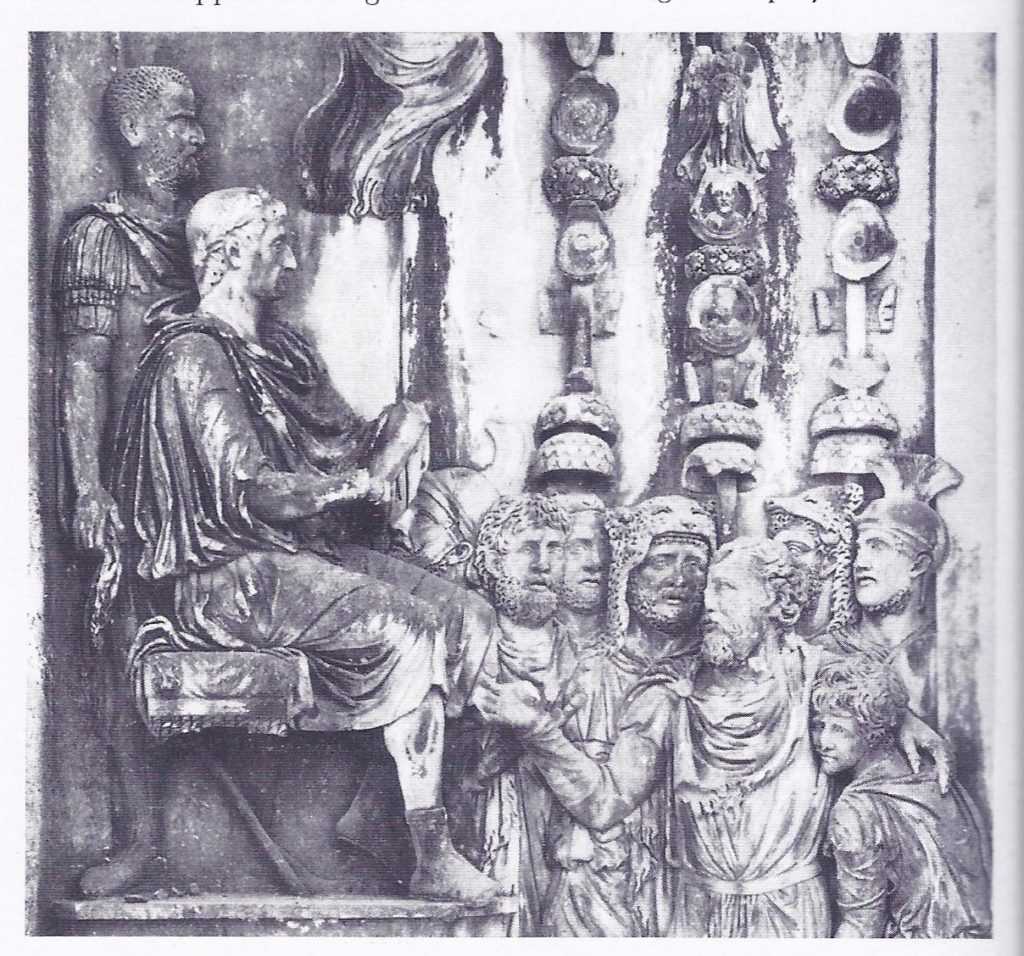

The Jewish revolt, which was apparently uncoordinated, was eventually suppressed by Varus, the Roman governor of Syria, who intervened with two legions and ruthlessly crushed the rebels, two thousand of whom he crucified. What was to be the future government of Herod’s kingdom was decided by Augustus, the Roman Emperor. He seems not to have regarded any of Herod’s sons as being capable of succeeding their father in the sole rule of the kingdom. Consequently, he divided it: one son, Archelaus, was appointed ethnarch of Judaea and Samaria; another, Herod Antipas became tetrarch of Galilee; a third son, Philip, received other territories outside Palestine proper, also with the title of tetrarch. So far as Judaea and Samaria were concerned, this arrangement lasted only till A.D. 6. Archelaus, having proved an incompetent ruler, was deposed and Augustus put his ethnarchy under Roman rule.

The Prefect and the High Priest

To implement the decision, a Roman governor — called praefect or procurator —was appointed. Under the new order, the Jewish High Priest was recognized by the Romans as the head and representative of the Jewish people. He was given control of domestic affairs and jurisdiction over his people in matters relating to Jewish law. The Jewish priestly aristocracy, since it was not popular with the people, naturally tended to be pro-Roman in its attitude. The maintenance of Roman rule guaranteed the continuation of its own favoured position in the Jewish state.

Roman tribute

One of the first actions taken by the Romans on incorporating Judaea into their Empire was to order a census for the purpose of assessing tribute. The Jews had been accustomed to pay tribute to Herod. They hated Herod; but he was a Jewish king and their tribute went to the maintenance of a Jewish state, but the imposition of Roman tribute was another matter; it gravely affected their religious principles.

The fact that it did so was immediately made clear by a rabbi, Judas of Galilee, who was backed by Sadduq, a Pharisee. Judas told his fellow-countrymen that the payment of tribute to Rome would be an act of apostasy towards Yahweh. Obedient to Judas’ exhortation and despite the contrary advice of Joazar, the High Priest, that they should submit to the tribute, many Jews rose in revolt. They were rigorously put down by the Romans and Judas of Galilee and many others perished.

However, the teaching and example of Judas were not forgotten. Many of his followers took to the deserts of Judaea, to wage guerrilla warfare against the Romans. The members of this “resistance” movement, which was led by the sons of Judas of Galilee, were called Zealots, because of their zeal for the cause of Yahweh.

Pontius Pilate

This unpropitious start to Roman rule in Judaea was followed by some twenty years of internal peace. This conclusion is drawn from the fact that Josephus mentions nothing during the period. Perhaps the ruthless suppression of the revolt in A.D. 6 had cowed the Jews. Whatever the cause, trouble started again in 26 when Pontius Pilate was appointed as governor.

Since the public ministry of Jesus and his crucifixion took place during Pilate’s term of office (26-36 . interest in the happenings of these years is naturally very great. Pilate’s involvement with Jesus; for Pilate’s career we are completely dependent on the accounts of Josephus given in his Jewish War and Jewish Antiquities and on a tractate written by Philo of Alexandria. The accounts of Josephus are intrinsically problematic because out of the ten years – Pilate’s term of office only three events are narrated. Philo’s account also raises difficulties, since the incident which he describes is not mentioned by Josephus.

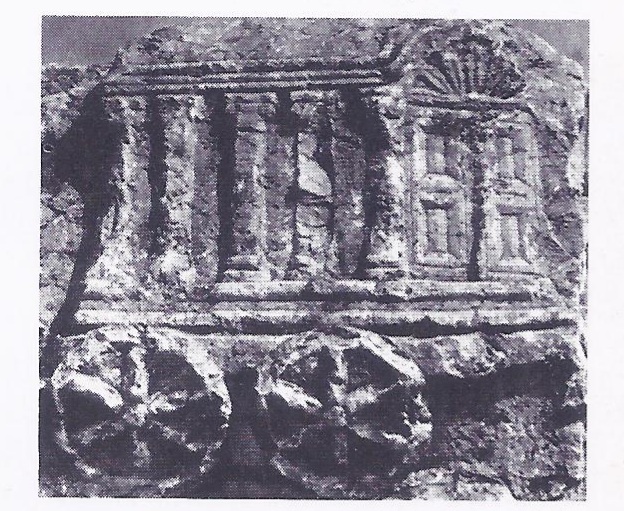

Affair of the Standards

Josephus begins his account of Pilate with an incident that must have happened shortly after his arrival in Judaea. It had apparently been the custom of previous governors, out of deference to Jewish religious scruples concerning graven images, to arrange for troops on garrison duty at Jerusalem to remove the effigies of Roman gods from their standards before entering the holy city. Pilate canceled this arrangement. When the Jews of Jerusalem saw the images displayed on the standards, they were horrified. According to Josephus, they flocked in crowds to Caesarea, to beseech Pilate to countermand the order. Pilate was obdurate and tried to frighten them into submission. Faced with their readiness to die for their religion, he at last relented. Josephus claims that Pilate was acting on his own malevolent decision in this matter. There is, however, much reason to think that the governor was obeying orders from Rome.

The Aqueduct

The next clash, recorded by Josephus, occurred over the building of an aqueduct. Jerusalem needed more water, so Pilate had the aqueduct built and defrayed the cost from the Temple treasury. Since this money was sacrosanct, there was a great uproar, which Pilate suppressed with heavy Jewish casualties.

The Gilded Shield

The incident related by Philo is curiously similar to that of the standards. This time Pilate placed some gilded shields, dedicated to the Emperor Tiberius, on the Herodian palace in Jerusalem, which the Romans used as their headquarters. The Jews immediately objected. Their reason is obscure. Since the shields bore no images, their offense probably lay in the inscription, which might have mentioned the divinity of the Emperor. After a fierce altercation and a Jewish appeal to Rome, Tiberius ordered the shields to be removed to the Temple of Augustus in Caesarea.

Pilate and the Samaritans

According to Josephus, Pilate’s career as governor was terminated by his savage action against the Samaritans. These people, whom the Jews regarded as heretics, met in arms at their sacred Mount Gerizim, stirred up by some Messianic prophet. Pilate, fearing a revolt, promptly intervened with force, and heavy Samaritan casualties resulted. The Samaritan leaders complained to Vitellius, the legate of Syria, who ordered Pilate to Rome for trial. However, before he reached there, Tiberius had died, and Pilate passes out of history into Christian legend.

These accounts of Pilate’s relations with the Jews, even allowing for the manifest distortions of Josephus and Philo, are significant. They reveal the basic impossibility of the Jews living ever peaceably under Roman rule. Quite apart from Roman harshness, which many other peoples also resented, Jewish religion made submission intolerable.

Caligula’s threat

Jewish suspicions concerning Roman intentions against their religion were not, however, groundless. In A.D. 39 their worst fears were realized. The Emperor Caligula, who was probably mad, believed passionately in his own divinity. Knowing this, the gentile inhabitants of the Jewish city of Jamnia erected an altar to him, for the purpose of offering sacrifice to his divinity. The altar was promptly destroyed by the Jewish inhabitants. Caligula, enraged by this affront to his divinity, ordered Petronius, the legate of Syria, to prepare a colossal gilt image of himself, in the guise of Zeus, for erection in the Temple at Jerusalem. The Jews were horrified at the projected sacrilege. Petronius procrastinated, fearing that the attempt to set up the statue in the Temple would be met by a fanatical revolt of the whole people. The situation was approaching a crisis when Caligula was murdered in Rome.

The Temple seemed thus to have been miraculously saved from most awful desecration—a desecration which paralleled that of the “Abomination of Desolation” erected by Antiochus Epiphanes in 167 B.C. The jews were profoundly thankful for their deliverance, but the threat from which they had so narrowly escaped remained to haunt them with the fear that it might be renewed by another emperor.

King Agrippa

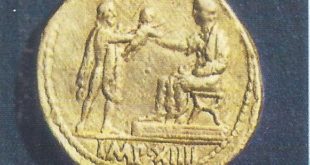

After the death of Caligula, independence under a Jewish king unexpectedly came to Israel. This sudden change of fortune was due to the gratitude felt by the new Emperor Claudius towards the Jewish prince Agrippa, who had helped him to secure the imperial throne. As a reward, Claudius appointed Agrippa King of the Jews. Although he was of Herodian descent, being a grandson of Herod the Great, Agrippa was a pious Jew. His devotion to Judaism won him the approval of his subjects. However, this happy situation lasted only four years, for Agrippa died in the year 44.

Agrippa’s death was a bitter blow to the Jews. For Claudius, passing over Agrippa’s son on account of his youth, placed Judaea back again under direct Roman rule. The brief interlude of national independence seems to have made the re-imposition of Roman rule even more intolerable. The revolt had fatal consequences.