Jesus of Nazareth, his life and death, for Romans alive about A.D. 30 was of no significance whatsoever. In the context of Roman history, Jesus was just another rebellious troublemaker. After the revolt of Spartacus thousands of slaves had been crucified in the same way as Jesus. His death was merely one more item in the list of repressions that Rome found necessary to carry out in order to consolidate her power. Yet in the end, the religion founded by Jesus would take over the Roman Empire itself and eventually make its way all over the world. The consequences for the subsequent history of civilization were incalculable.

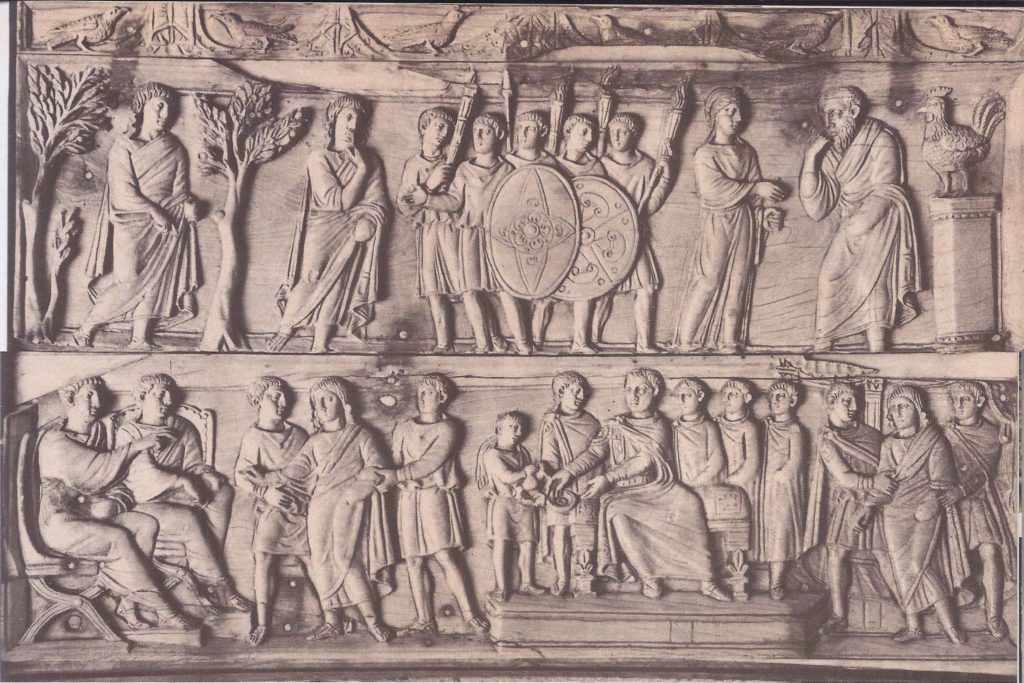

Writing early in the second century, the Roman historian Tacitus told his readers how Nero had been suspected of burning Rome in A.D. 64. To free himself from suspicion, the infamous Emperor “fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their vices, whom the people called Christians. Christus, from whom the name derived, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius on the order of the procurator Pontius Pilate. The pernicious superstition, suppressed for the moment, broke out again, not only in Judaea, the source of the evil, but in Rome itself… . Accordingly, acknowledged members of the sect were first arrested; then, upon their evidence, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much of the crime of firing the city, as of hatred of mankind.”

This significant passage from the Annales of Tacitus shows what an educated Roman knew and thought about Christianity some eighty years after its birth. To him it was a dangerous subversive movement whose founder had been executed for sedition by the Roman governor of Judaea; but that had only temporarily checked the movement and it had spread from Judaea to the underworld of Rome. Nero had found that the Christians were convenient scapegoats for the fire; for people already believed that Christians hated mankind.

We need not accept as accurate this damning estimate of primitive Christianity. Yet it is important historical evidence because it is the earliest non-Christian source; all our other information comes from Christian writings that were inspired by theological and not historical, interests. This fact constitutes a fundamental problem for the historian of Christian origins, for it is his task to understand how Christianity began as a historical movement. The Christian Gospels purport to give factual accounts of the life of Jesus of Nazareth; but these writings are based on the assumption that Jesus was not just a man, but that he was the Son of God, sent by God into this world to save mankind. This assumption involved some very complex theology ; it had nothing to do with historical fact.

These theological ideas, nevertheless, are of historical importance, because they form the basis of Christianity—and the birth of Christianity is certainly one of the most important milestones of history. The historian, therefore, must explain how such ideas originated and trace how they developed into the religion we know as Christianity. We must also explain who Jesus of Nazaeth was; what he taught and did, as an historical person. There have been thinkers who have denied that Jesus ever existed and have regarded him as a mythical figure. This view is no longer held by responsible scholars, but there is much conflict of opinion about what can reasonably be accepted as historical fact about both the person and career of Jesus.

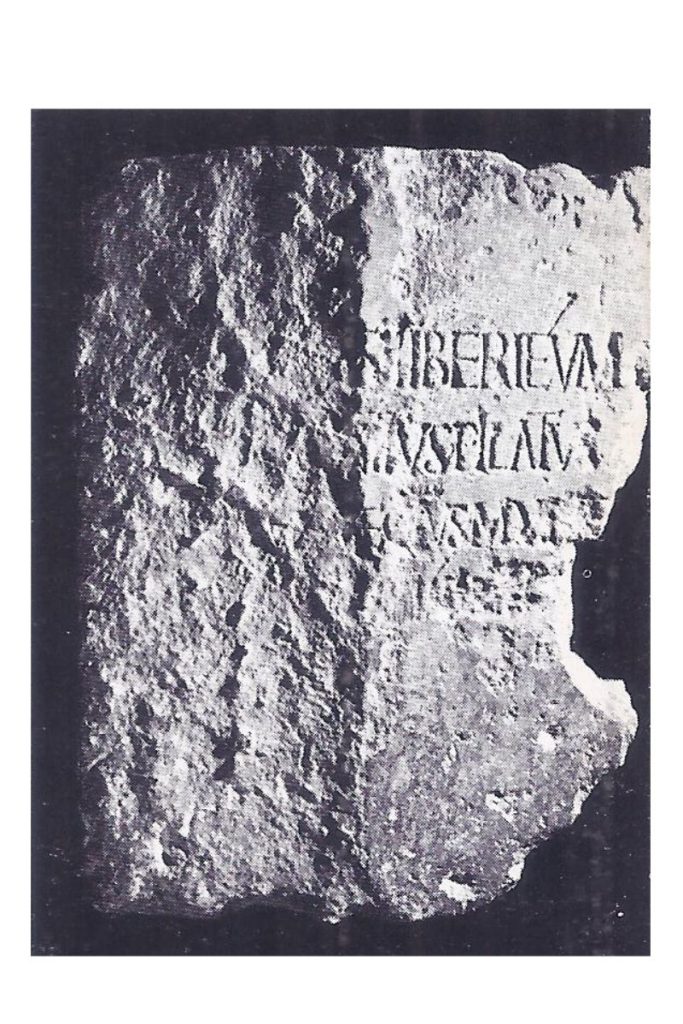

Ironically, the most certain fact that we know about Jesus is that he was crucified by the Romans for sedition against their government in Judaea. The Roman governor who ordered his execution was Pontius Pilate, who held the office of Governor of Judaea from A.D. 26 to 36. We can be certain of this one fact because the Roman execution of Jesus is recorded not only by the Roman historian Tacitus, but also by the authors of the four Gospels, who might have wished to suppress such damaging evidence. That Jesus of Nazareth had been crucified for sedition was indeed an embarrassing fact. For Christians it meant that their master had been regarded as a rebel against Rome and that they were likely to be incriminated as well.

The early Christians would probably have preferred to keep quiet about the execution of Jesus, but the fact was too well known to conceal. Instead, they attempted to show that Jesus was really innocent of sedition. A large part of each of the four Gospels is devoted to the trial and crucifixion of Jesus. The Gospel of Mark, earliest of the four, sets the theme for the others by endeavoring to show that the death of Jesus of Nazareth had been plotted by Jewish leaders who hated him. These leaders, Mark points out, condemned Jesus to death for blasphemy in their own court, the Sanhedrin; but they lacked the authority to execute him. Consequently, they handed Jesus over to Pilate, charging him with sedition against Rome. Pilate was not convinced by the charge and sought to release Jesus. His efforts, however, were frustrated by the Jewish leaders, who stirred up the mob to demand the crucifixion of Jesus. Pilate was forced to accede and so, at last, ordered the execution. Hence, according to the Gospels, Jesus was really the victim of the malevolence of the Jewish leaders and the weak character of Pontius Pilate.

The most certain fact we know about Jesus of nazareth thus entails a problem: Christian, evidence admits that Jesus was executed for sedition against Rome; but it also maintains that he was innocent. Can this claim be accepted? This question is basic to all understanding of Jesus as an historical person.

If Jesus were really a rebel against the Roman government in Judaea, he would have been very different from the gentle person Christian doctrine holds him to be. At the same time, he would be more intelligible historically, for among the Jews of his time there was a fierce hatred of Roman rule. That rule was an affront to their religion since they fervently believed that they were the Elect People of their god Yahweh and should not be subject to a heathen lord. To them Judaea was Yahweh’s holy land and its produce should not be given in tribute to the Roman Caesar. Many Jews, in fact, refused to submit to Rome and died as martyrs for Israel’s freedom. The usual Roman penalty for rebellion was crucifixion. Hence the problem: did Jesus of Nazareth also die as a martyr for Israel’s freedom? Or was he obedient to Rome, as the Gospels make out and was his crucifixion due to the Jewish leaders?

Long and complex research has been devoted to these problems. All we can do here is outline some possible answers.

The Gospel accounts of the trial of Jesus reveal a strong apologetic motivation. The early Christian authors were obviously concerned with transferring the responsibility for the crucifixion of Jesus from the Romans to the Jews. Their purpose in so doing was a result of the situation in which the Christians found themselves after A.D. 70. That year marked the end of a four-year-long Jewish revolt against Rome and anti-Jewish feelings had grown intense among the Romans. The Gentile Christians, consequently, found themselves in a dangerous and perplexing situation. The Jewish origins of their religion were well known; so, too, was the awkward fact that Jesus of Nazareth had been executed by the Romans as a rebel. To the Roman authorities and people, all Christians were suspected of being sympathetic to Jewish nationalism and to Messianic fanaticism.

The Gospel of Mark deals with this dangerous situation as it affected the Christians of Rome about A.D. 71. Mark’s attempt to turn Pilate into a witness to the innocence of Jesus and make the Jews solely responsible for his death breaks down under critical analysis. This is also the case when the accounts of the trial of Jesus in the other Gospels are examined. We must conclude, therefore, that the Romans crucified Jesus as a rebel because they deemed him to be one.

This conclusion, necessarily summarized here, is confirmed by an abundance of cumulative evidence from various sources.

Something of the career of Jesus of Nazareth as a historical person can be reconstructed from a critical appraisal of the Gospels. A native of Nazareth in Galilee, Jesus was at first associated with John the Baptist. John announced, in the tradition of Hebrew prophecy, the imminence of the kingdom of God and sought to prepare the Jews for this fateful event by a baptism of repentance. Jesus, perhaps after the arrest of John by Herod Antipas, carried on the mission. He achieved a measure of success in Galilee, but soon encountered opposition from the Jewish authorities. Jesus then became convinced that it was these authorities who were delaying Israel’s preparation for the kingdom of God.

By his followers and by many of the people, Jesus of Nazareth was recognized as the Messiah, God’s chosen agent for the redemption of Israel. He also undoubtedly so regarded himself. At this stage in his ministry, Jesus was probably more concerned with the opposition of the Jewish authorities than he was with the Romans, for Galilee was then ruled by a Jewish prince, Herod Antipas. Jesus came into direct contact with the Romans only when he visited Jerusalem, which was in Judaea. The Jewish authorities in Galilee, however, were closely associated with the Roman rule of Judaea, for Jerusalem was the religious centre for all Jews. The High Priest at Jerusalem was actually appointed by the Roman governor to control “native” affairs and maintain good order among his people. Consequently, both the High Priest and the Sadducean aristocracy, of which he was a member, were suspicious of any popular movement likely to disturb the peace. The movement led by Jesus appeared to be just such a disturbance.

The priestly aristocracy, headed by the High Priest, controlled the Temple of Yahweh at Jerusalem; their position gave them great authority as well as a rich income. Seeing them as the chief obstacle to Israel’s conversion, Jesus of Nazareth finally decided to challenge their control of the Temple. Accordingly, with his disciples and Galilean followers he staged a Messianic entry into Jerusalem at the feast of the Passover. Gathering support, he attacked the trading activities of the Temple. These activities were a profitable source of revenue to the priestly aristocrats and Jesus’ attack was obviously a far more serious affair than the Gospels represent it to have been. It is even possible that Jesus intended to seize the Temple and reform the priesthood, as the Zealots were later to do in A.D. 66. The outcome of Jesus’ bold move is difficult to assess. It would seem that he did not achieve complete success; but his supporters remained too numerous for the Jewish leaders to arrest him publicly.

After this so-called “Cleansing of the Temple,” Jesus of Nazareth stayed on in Jerusalem, although he withdrew from the city each night. He seems to have been uncertain of his next move. The question that the historian must now face is whether the action of Jesus in the Temple had been connected with a Zealot operation. We learn from the Gospels that at this Passover there had also been an armed rising against the Romans, apparently led by Barabbas, which seems to have imvolved the Zealots. That two uprisings, one against the Jewish authorities and one against the Romans, should have occurred in Jerusalem at the Passover is certainly remarkable. The coincidence suggests that there may have been some connection between the two events.

Jesus continued his stay in Jerusalem until the night of the Passover feast, which he ate with his disciples within the city. By then he probably realized that his attempt to challenge the authorities had failed and that it would be wiser to withdraw to Galilee.

Christian tradition records that, in Gethsemane that night, Jesus experienced an agony of indecision. However, the initiative suddenly passed from him to his enemies. One of his apostles, Judas Iskariot, had defected and betrayed his rendezvous to the Jewish leaders. Taking no chances, they sent a heavily armed band to arrest Jesus. After an armed struggle in the darkness, the disciples fled and Jesus was taken. During the rest of that night the Jewish authorities interrogated him about his aims and his disciples, so that they could draw up a charge preparatory to handing him over to the Romans. In so doing, the High Priest was discharging his duty to the Roman government.

The High Priest charged Jesus with sedition. particularly for his claim to be the Messianic King of Israel. It is possible that he also accused Jesus of being the real leader of the recent rising against the Romans, thus exonerating Barabbas who was under Roman arrest. In other words, it is likely that Jesus was charged with heading a two-pronged attack: on the Jewish authorities in the Temple and on the Romans, in the Antonia Fortress and Upper City. What is certain is that Pilate condemned Jesus. The titulus which he ordered to be placed on the cross above the crucified Jesus, is evidence of the political nature of the charge: “This is Jesus the King of the Jews.”

The crucifixion of Jesus as a rebel by the Romans was not an extraordinary event in the light of contemporary Jewish history. Thousands of other Jews similarly perished, either as leaders or supporters of revolt. Fom this point onwards Christian tradition makes even more problematic the search for historical fact about Jesus. It was the usual practice for the bodies of executed criminals to be buried in a common grave. According to the Gospels, this did not happen to the body of Jesus. Instead, a disciple named Joseph of Arimathaea obtained the body from Pilate and buried it in a rock-hewn tomb of his own. Three days later, the tomb was found to be empty. Subsequently a series of visions, in which the crucified Jesus appeared to various disciples, convinced his followers that Jesus had risen from the dead. The visions were, significantly, limited to the disciples of Jesus; no one outside their fellowship is recorded to have had a similar experience. According to Christian tradition, these appearances of the Risen Jesus continued for forty days.

It is difficult to evaluate these traditions of the Resurrection of Jesus. Although the physical reality of the Risen Jesus is stressed, it is never asserted that he resumed his life on earth; instead he is said to have ascended to heaven. Whatever the truth of the traditions about the Risen Jesus, there can be no doubt that from the disciples’ faith in it. Christianity was born.

When the original disciples of Jesus became convinced that he had risen from the dead, their faith in his Messiahship revived. In the light of their new conviction, they had to adjust their own Jewish ideas. According to contemporary belief, the Messiah would overthrow the nation’s oppressors and “restore the kingdom of Israel.” However, Jesus had been executed by Israel’s oppressors: how could he, then, be the Messiah? The disciples soon found a solution in Holy Scripture. The prophet Isaiah had spoken about a suffering Servant of Yahweh and the disciples applied this prophecy to Jesus. It is because of Israel’s sins, Jesus had died as a martyr; but God had raised him up. He would soon return, with supernatural power, to fulfill his Messianic role and redeem Israel.

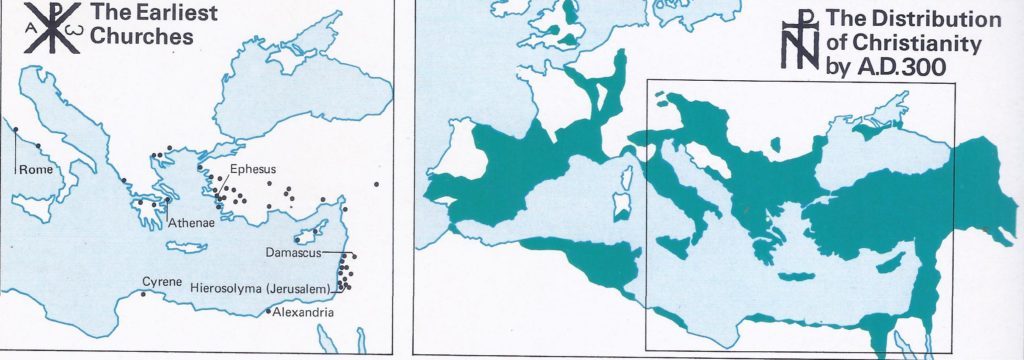

So the Christianity of the original disciples was essentially a Jewish faith. They probably never contemplated that it would lead to a new religion distinct and separate from Judaism.

The transformation of Christianity from a Jewish Messianic sect into a universal salvation-religion, centered on Jesus, was due to Paul of Tarsus. Paul had not been an original disciple of Jesus. In fact, he had at first fiercely rejected Jewish Christianity because it preached a “‘crucified Messiah’ — a scandalous thing to a pious Jew — and helped persecute members of the movement. Suddenly, however, Paul had a profound spiritual experience, which he attributed to the intervention of God. He became convinced that God had chosen him to reveal Jesus to the Gentiles, in a completely different guise from the one presented by the Jewish Christians. The Jewish Christians, in fact, had not even considered their faith in Jesus as being applicable to non-Jews.

Paul’s new conception of Jesus drew its inspiration from Hellenistic ideas rather than from Judaism. The Gnostic philosophy, which was widely followed in Syria and Alexandria and farther east, held that all mankind was enslaved by demonic powers and taught how Gnosticism could save men from their subjection to the demonic vein, taught that God had sent Jesus into the world to save men from their subjection to the demonic rulers of the planets.

It was a very esoteric doctrine but one that Greco-Roman society of that time could understand and appreciate. Jesus was presented by Paul as a saviour-god, who had died and risen again. Through the sacrament of baptism, Christians were ritually identified with Jesus in his death and resurrection. In consequence, they were reborn to a new risen life in Christo.

Paul’s new “gospel” was repudiated by the Jewish Christians of Jerusalem. They also rejected his claim to be an apostle and sent out emissaries to his converts to present their own “gospel” as the true and original form of Christianity. Paul’s teaching might easily have been finally discredited and lost, but in A.D. 70 the Mother Church of Christianity at Jerusalem itself perished in the destruction of the city by the Romans. Christianity was thus freed from its primitive involvement with Judaism and Paul’s version of Christianity survived and set the pattern for the entire faith.

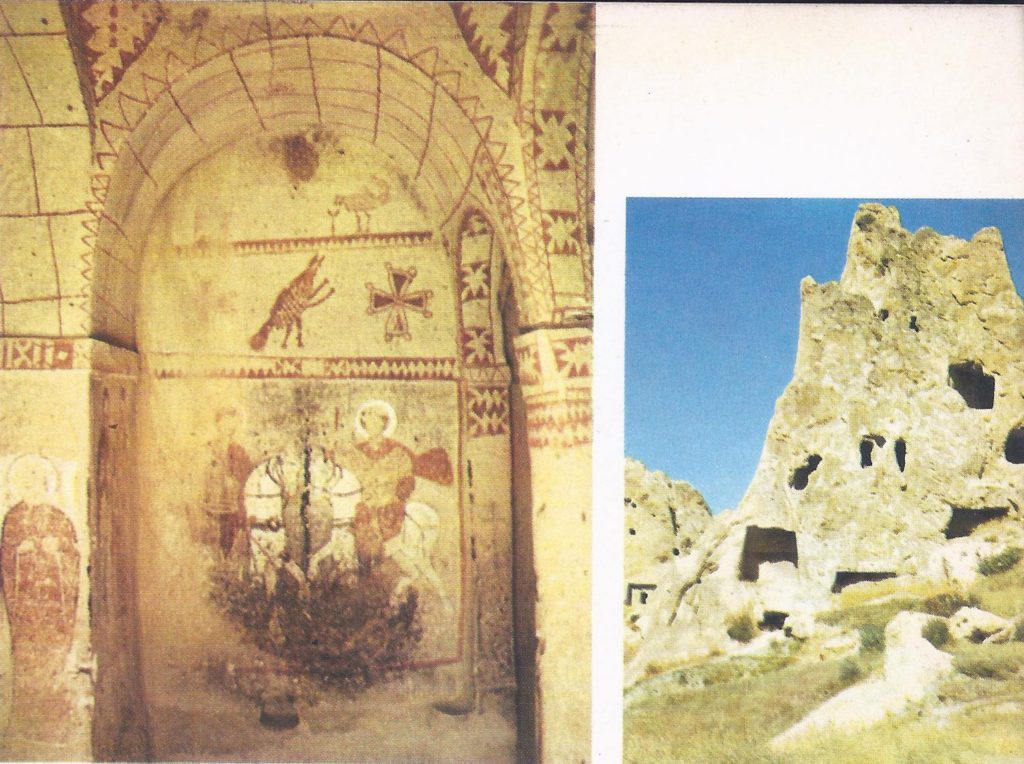

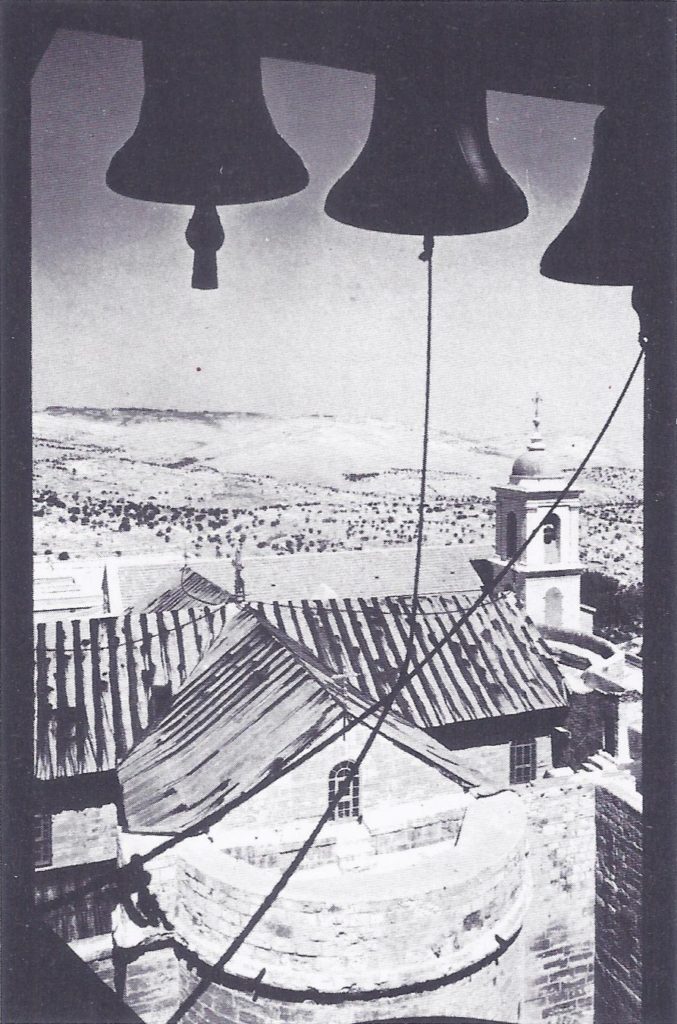

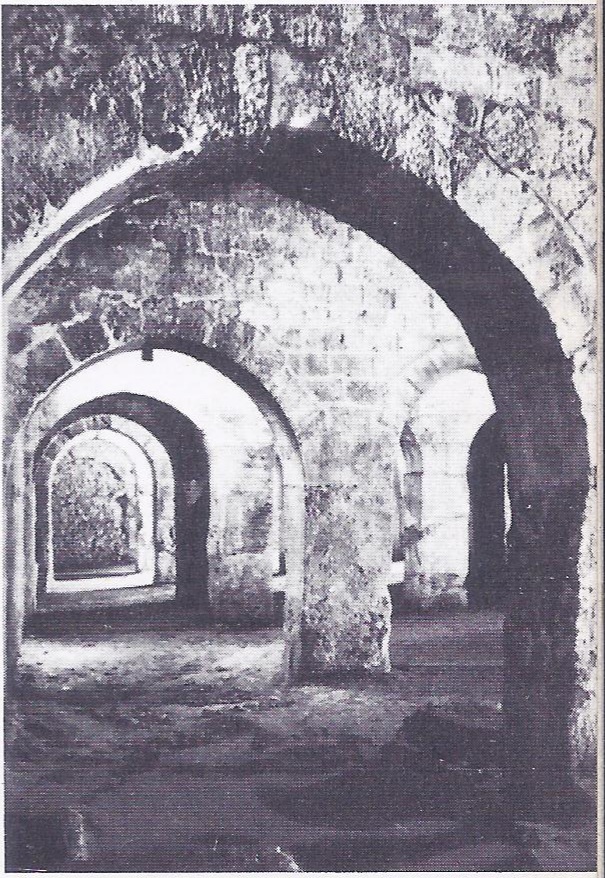

Before the destruction of Jerusalem, Christianity had already spread outside Palestine. It moved mainly northwestwards, through Syria and Asia Minor, to Greece and Italy, although it was also established at an early date in Egypt. Freed from its Jewish cradle, Christianity quickly adapted itself to the spiritual needs of Greco-Roman society and eventually even survived the downfall of the Roman Empire in the West. The subsequent conversion of the barbarian peoples, who were to form the new nations of Europe, gave the Christian Church immense influence and power. The civilization of medieval Europe was, indeed, essentially the product of Christianity and the later predominance and diffusion of the European peoples throughout the world, made Christianity a cultural force of universal influence.

The Christian system of chronology still proclaims, even in a secular world, the decisive nature of the birth of Jesus — though ironically, it sets the event at least four years too late. By the sixth century, Christians regarded the birth of Jesus as so significant a turning point in world history that they reckoned time from it — the Anni Domini (A.D.), the “years of the Lord,” that continue to designate our present era.