Both Sparta and Athens were determined to fight, — so determined that they had behaved outrageously towards Persian ambassadors who had visited them to demand submission. The traditional way of doing this was to ask for “earth and water” but when the ambassadors made this demand in Athens they were thrown into the pit where criminals were put. “Get earth from there”, yelled the citizens. At Sparta the ambassadors were plunged into a well. “Get water from there”, they were told. Throughout history the person of an ambassador has been held sacred and if the Persians had won at Marathon the Greeks would no doubt have been quick to attribute defeat to the anger of the gods, aroused by Spartan and Athenian insolence. However, when news of the Persian landing reached Athens, nobody was worrying about how the Persian ambassadors had been treated. There were two vitally important things to be done. An army had to be put into the field and the Spartans had to be summoned. The story of the summoning of the Spartans is famous but strange. It says that a runner called Pheidippides made the journey (140 miles) on foot in two days. Seventy miles a day. We would consider that quite good going on a bicycle. Perhaps he was given a lift for part of the way. Why not have sent a horseman? The fact that a runner was preferred is a reminder of the hilliness of Greece and of the independence of the city-states. Nobody was interested in building a good road and making the journey from Athens to Sparta as easy as the journey from Susa to Sardis. On the contrary, it was in the interest of both Athenians and Spartans to keep the route rough. A hoplite. He wears a metal cuirass …

Read More »The Ionian Greeks

The Ionian Greeks, who lived on the coast of Asia Minor and the adjoining islands, had produced some of the leading poets and thinkers of the Greek world. Thales of Miletus (640-546 B.C.) predicted an eclipse of the sun and introduced geometry to the Greeks. Pythagoras of Samos (c. 500) won fame as a philosopher and mathematician, although it is not now thought that he discovered the geometrical truth which bears his name (i.e. that the square on the hypotenuse of a right-angled triangle is equal to the sum of the squares on the other two sides). Thales was interested in politics as well as mathematics and tried to unite the cities of Ionia into a federation. Each city-state would have renamed independent but would have sent representatives to a council to discuss affairs of common interest. This scheme did not succeed. The Ionian cities of the mainland (except for the largest, Miletus) became subject to Lydia and later, when Cyrus conquered Croesus (p. 21), they all became subject to Persia. Even some of the islands succumbed. Polycrates, the fabulously wealthy tyrant of Samos, whose position was such that he could enter into a treaty with the king of Egypt, was enticed by the Persians onto the mainland and killed (522). In the year 522 a pretender had seized the throne of Persia and some nobles, of whom Darius was one, joined in assassinating him. They then decided that they would ride out early in the morning and that the one whose horse neighed first after the sun rose should be King. Darius’s groom saw to it that his master’s horse neighed first and Darius became King of Persia. Neither fate nor the other nobles punished him for cheating in this way. He ruled Persia until 485, by no means …

Read More »Athenian Democracy

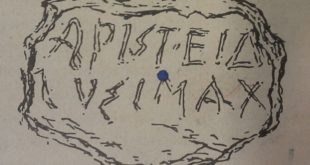

The heroism of Harmodius and Aristogeiton was a myth, but Athenian democracy was not. In the two great wars of the fifth century — the Persian and the Peloponnesian — the Athenians clearly felt they had what would now be called a “way of life” which was worth fighting for. Cleisthenes, although he was of nobler blood than Solon, gave more power to the poor than Solon had done. Nearly all Athenian citizens now had a vote in the Assembly, a body which approved laws discussed in the Council of Five Hundred. The Five Hundred were elected by the citizens and anyone over thirty could be a member. As well as taking his share in lawmaking and government a citizen also played his part as a juryman in seeing that justice was done. Even the archons could be brought to trial when their year of office was over, if they were thought to have misused their power. There was a kind of police force consisting of Scythian archers which Peisistratus had set up. But they were the citizens’ servants, not his masters. There is often a good deal of argument about what is meant by a “free” country. A useful test is to ask: Can police knock on the door in the middle of the night and take people away to death or imprisonment without a public trial? If this “knock on the door” question is asked about fifth-century Athens the answer to it would be: No. There were no secret police and there were no mysterious disappearances in the middle of the night. These privileges of citizenship, however, were not shared by everyone living in Attica. “An Athenian citizen” does not mean the same as “a resident in Athens”. Neither women nor slaves might vote and immigrants from other …

Read More »A Tyrant Who Was Not Tyrannical

A tyrant’s first problem was to seize power. Peisistratus had to solve this problem three times. In 560 he came before a meeting of the Assembly wounded and bleeding, alleging that his political opponents had attacked him. Sympathisers voted him a body-guard, with the aid of which he was able to seize power, but his opponents soon forced him to take flight. His next descent on the city was made in a chariot, in which he was accompanied by a handsome woman dressed up as Athena. He alleged that his companion was in fact Athena and that she had chosen him to rule her city. No doubt this escapade, if it really took place, impressed the simpler supporters of Peisistratus and amused the wiser ones. Anyway he again established himself as tyrant and after another short spell of power was again thrown out. This time he stayed away ten years. When he returned for the third time, in 546, he made a less spectacular entry than on previous occasions, but remained to rule until his death in 527. During that period his talent for display found a more useful outlet. He organised the annual spring festival of Dionysus, at which the great tragic dramas of the following century were performed and the Panathenaea, a festival in honour of Athena, which included the recitation of poetry as well as athletics and drew competitors from all over Greece. He saw to it that Athens had buildings and sculptures worthy of her guests. We have become so accustomed to thinking of Athens as the most splendid city in Greece that it is hard to realise how insignificant she was before about the year 600. Solon having prepared the way, Peisistratus put Athens on the map, not only by skillful showmanship but also by …

Read More »Solon

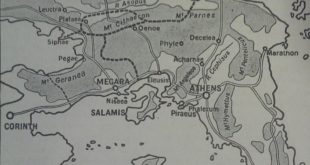

One of the young Athenians who must have taken a good deal of interest in Draco’s writing down of the laws was Solon. He came of a good family. His father had been extravagant and this had prompted Solon to become a foreign trader in order to repair the family fortunes. There was no question of his considering himself one of the oppressed. He was a “have” not a “have-not”. Yet Solon was destined to repeal almost all of Draco’s laws and to set Athens on the road to democracy. We first meet Solon as a poet, patriot and soldier. The possession of the island of Salamis was in dispute between Megara and Athens. Athens, to Solon’s disgust, renounced her claim. Solon rushed into the market place and recited a poem in which he appealed to the Athenians to reverse their decision and conquer the island. The poem had the desired effect. Solon was chosen to lead the attack and eventually Salamis became part of Attica. A little over a century later the decisive sea-battle of the Persian wars was fought in the stretch of water which separated Salamis from the mainland. Meanwhile discontent due to poverty and debt, had reached such a pitch, that the need for firm action was clear. Solon was liked and trusted. When he was elected archon in 594 B.C. he was able to begin a programme of reform. Solon’s first act was to free all those who had enslaved themselves on account of debt and make it illegal for any citizen to do so again in the future. Other measures were aimed at checking extravagance. For instance, not more than a certain sum might be spent on funerals or on the dowry of a bride. Last of what may be called Solon’s restrictive …

Read More »Athens

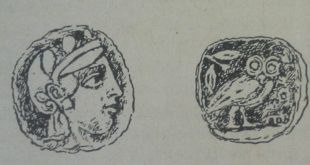

The legend of Theseus and the Minotaur suggests that Athens had dealings with Crete during the Minoan and Mycenaean Ages. We have no written history of that time, though the discoveries of archaeologists show that the Acropolis, a rocky mass 512 feet high, already had fortifications like those found at Tiryns and Mycenae. At the time of the first Olympiad (776 B.C.) there may still have been a King upon the throne, but at Athens, as in many other Greek states, government by Kings gave way about that time to government by the nobles. Monarchy, that is to say, gave way to aristocracy. Sparta with her two Kings was an exception. Whoever ruled Athens also ruled Attica. This was not a district of great natural riches. As can be seen from the map, much of it was mountainous and the corn grown on the plains was not enough when the population increased. However, olives and vines were plentiful and the mountains, as well as providing a home for goats and beet, contained silver mines, lead mines and marble quarries. In the river beds lay a reddish clay suitable for pottery. Finally, there were good harbours. Attica, therefore, though not rich, had considerable natural advantages and we shall see how well she used them — how the red clay was turned into pots and the marble into temples, while the harbours were crowded with merchantmen and ships of war. The most famous product of Attica was neither animal, vegetable nor mineral. It was the form of government known as democracy. We have now to see how democracy grew out of the aristocracy, or rule of nobles, which succeeded the period of the Kings. The Spartans had tried to prevent one man becoming much richer than another by using iron bars as …

Read More »A Spartan grows Up

A Spartan child was examined at birth. A healthy infant was allowed to live. Weaklings were not wanted. They were left in the mountains to die. (Exposure of unwanted children was not peculiar to Sparta. Even civilized 5th-century Athenians practised it.) At the age of seven a Spartan boy left home. His period of family life was finished. Thereafter he would be a member of a community. In modern terms, he would always be either at a boarding school or on military service. In the “pack”, as it was called, the seven-year-old newcomer quickly learned obedience. He had to act as a kind of servant to one of the older boys. He learned to be hardy, since even in winter he had to go barefoot and was only allowed a single garment. He learned to use initiative and was even encouraged to steal in order to increase his rations, which were purposely kept small. It was one of these thieving raids which gave rise to the story of the Spartan boy and the fox. The boy had stolen a fox and hid it under his cloak. It began to gnaw at his stomach, but to set it free would have meant discovery. The boy therefore let it go on gnawing and at last fell down dead, but with his honour preserved. The incidentals of this story are puzzling. If the fox was stolen, it must presumably have belonged to someone. Was it a pet? It seems an odd animal to steal if you are hungry. However, there is no doubt about the moral. Death to a Spartan, even in boyhood, was preferable to the taint of cowardice. The education of girls was milder; but compared with the education of Athenian girls it was tough and unrestricted. At Athens athletics were …

Read More »Sparta

This striking difference in the way Athens and Sparta treated their victorious athletes reflects a striking difference between the states themselves. Neither was important as a coloniser. But during the 6th and 5th centuries they occupy the centre of the stage. At Sparta living was hard; hence the adjective “Spartan”. In the Mycenaean Age, when, according to legend, Menelaus was King of Sparta and Helen was his queen, the place had not yet gained this reputation for hardness, which was a result of the Dorian invasion. The invaders found the valley of Lacedaemon attractive. They settled there and made the district round Sparta the centre from which they governed. They did not mix with the previous inhabitants of the country. They enslaved them. These slaves, called Helots, were much more numerous than the Spartans themselves. As a result of two wars (c. 736 and 650 B.C.) against the pre-Dorian inhabitants of Messenia, the Spartans reduced them also to Helot status. In spite of their military strength the Spartans were at this time still a cultured people, honoured for their poets and musicians and it was to one of their wise men, Chilon, that the celebrated Greek maxims “Know thyself” and “Nothing in excess” were ascribed. Their craftsmen produced fine pottery and ivory carvings. It was probably not till after the second Messenian war that the Spartans, in order to keep control of their greatly increased Helot population, began that system of cheerless, iron discipline which made them famous. Tradition attributed its introduction to a certain Lycurgus. How much Lycurgus had to do with the moulding of the Spartan system, or whether he ever existed at all, we do not know. It is the system itself which is important, because it did not change very much throughout the next three centuries …

Read More »The Olympic Games

At Olympia every four years Olympic games were held in which any Greek was entitled to take part. It is not known when the first Olympic games were held, but they were said to have been revived in the year 776 B.C. and the Greeks used that year from which to reckon dates. The period of four years between each celebration of the olympic games was called an Olympiad. When therefore a Greek writer says something happened in the year of the . . . Olympiad we can calculate the year according to our system and put it down as . . . B.C. From now onwards Greek history becomes more exact. Like Delphi, Olympia became a place where men from any part of the Greek world might meet. For a month every four years the incessant quarrels of the city-states were stopped and during five days of this truce period the olympic games were held. There was running, long jump, boxing. wrestling, throwing the discus or javelin, chariot racing and horse racing (all individual events — no team games) and no Marathon. The only prize at Olympia was a crown of wild olive, but when victorious, competitors reached home they were given a variety of honours and rewards. At Athens they received a large sum of money and the right to free dinners for life (cf. p. 60). At Sparta they were assigned the post of honour in battle.

Read More »The Delphic Oracle

The Delphic oracle, the priestess of Apollo, was supposed to have the gift of prophecy. The Delphic Oracle was consulted before a colony was founded, before war was declared and on all sorts of other questions. When a request for advice was put to her through her priests she proceeded to put herself into a trance. She is said to have done this by chewing laurel leaves, drinking water from an underground stream and inhaling an evil-smelling gas which arose through a cleft in the rocks within her shrine (but no traces of this cleft have been found). Finally, seated on a tripod, she spoke. The priests claimed to be able to make sense of her utterances. After listening, they presented a reply, in verse, to the questioner. The priests acquired great power, but if they had abused it grossly, Delphi would not have maintained its importance for centuries, as it did. Replies to political questions obviously had to be ambiguous, but when consulted on private affairs the oracle tended to be on the side of what we would now consider right (e.g. in favour of mercy and against fraud). It was not, however, the formal reply alone which made a visit to Delphi worth while. As at international conferences nowadays, all sorts of informal meetings and conversations must have taken place. Nowhere else could one find out so much about the scattered communities of the Greek world.

Read More »