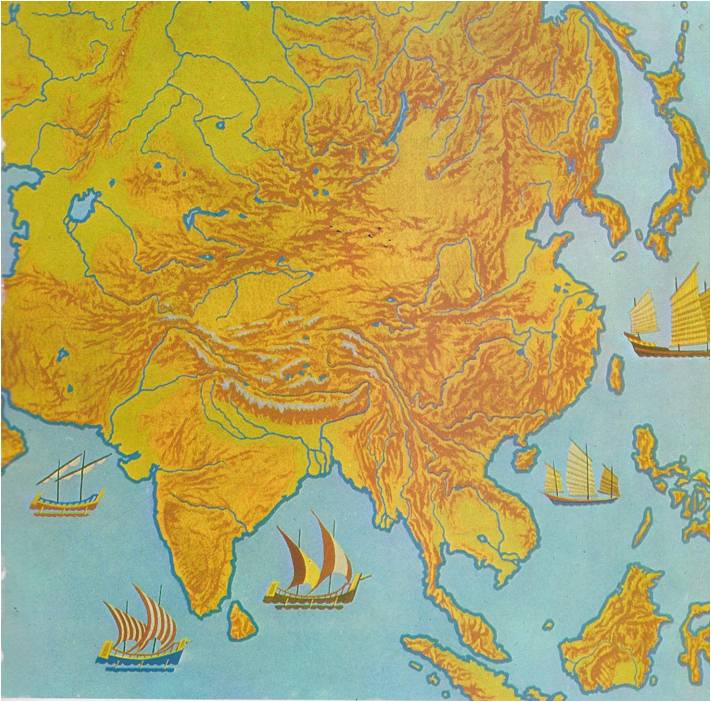

UNTIL 1947, when the Moslem state of Pakistan was carved out of its western and eastern corners, the entire triangle of land that points south from the Himalaya Mountains into the Indian Ocean was known as India. Geographers call this huge land mass a subcontinent, because it is almost completely cut off from the rest of the continent of Asia. The Himalayas on its northern frontier form a continuous barrier of rock, the highest in the world.

“MOTHER GANGES”

From the southern slopes of the Himalayas, two great rivers run down to the ocean. The valley of the Indus River, on the west, is mainly desert; overlooking it are the only breaks in the Himalayan wall, the Khyber Pass and the Bolan Pass. The valley of the Ganges River, on the east, is a broad, fertile plain. Indians consider this river holy and call it “Mother Ganges.” Together, the Indus and Ganges Valleys make up North India.

South of the Ganges Plain rise the Vindhya Mountains. To the south stretches a very large region of hilly uplands, called the Deccan. At its western and eastern edges the Deccan drops suddenly to coastal plains, forming long mountain walls called Ghats. The Vindhyas, the Deccan, the Ghats and the strips of lowland along the coasts make up South India.

INVADERS FROM THE NORTH

Geography influences history. This is particularly true of India — so much so, in fact, that North and South India have really had two separate histories. From earliest times, the people in both parts of the country were mostly poor farmers, living in villages. They shared the beliefs of the Hindu religion. Hinduism taught them that life was only a dream, they paid little attention, north or south, to the events that took place in their lifetimes. Otherwise, however, the plains dwellers of North India and the hill people of South India had hardly anything in common.

They even looked different. The people of South India were rather short and had skins that ranged in color from tan to brown. The people of North India were taller and had lighter-colored skins. Outsiders had left the southerners to themselves, finding their jungles too thick to get through and their mountains too rugged to cross. The north, on the other hand, had been overrun time and again by invaders from beyond the Himalayas. These invaders — tall, blond and blue-eyed — had mingled their blood with that of the people they found there.

The first people to invade after the start of the Christian era were Central Asian nomads called Kushans. Under their leader Kanishka (120-162) the Kushans set up a state in northwest India and Afghanistan. Several peoples and civilizations — Greek, Persian and Indian — came together in the Kushan Empire. Several religions, including Christianity and Zoroastrianism, competed with Hinduism. Kanishka, who was a great patron of the arts, became a Buddhist. Buddhism was not separate from Hinduism, but part of it. It was a philosophy and way of life based on the teachings of Gautama Buddha, an Indian prince who had tried to reform the age-old religion of his countrymen five centuries before Christ.

After Kanishka died, his empire broke up. In both North and South India, rival kings battled for power, but none ruled for long. Then, in 320, a chieftain named Chandragupta became the head of a state in the Ganges Plain and boldly proclaimed himself Maharadhiraja, the king of all kings. He announced the start of the Gupta Era, gupta meaning “protector,” and began to make good his boast by invading a neighboring kingdom. He and his son and grandson expanded their domain until it took in almost all of North India, from the Arabian Sea to the Bay of Bengal and from the Himalayas to the Vindhyas.

Chandragupta’s grandson, Chandragupta II, who reigned from 380 to 415, was the greatest of the Guptas. He was also one of the outstanding Indian rulers of all time. Under him, the Hindu priests, or Brahmins, again favoured Buddhism, as in Kanishka’s day, although the ordinary people remained devoted as always to orthodox Hinduism, with its colourful gods and goddesses, romantic legends and dramatic rituals. Writers turned out many books in Sanskrit, the sacred language of the Brahmins. Sculpture, for which Indians have always shown a particular talent, became refined to a point that has never since been equaled.

With Chandragupta’s successors, the glory of the Guptas faded. Nevertheless, the great emperor’s grandson, Skandagupta ( 45 5-480), earned the gratitude of his countrymen by turning back an invasion by ferocious Central Asian tribesmen called Huns. He thus saved India from the terrible fate that befell eastern Europe at their hands. In the sixth century, the Huns swooped down again from the Himalayan passes, but in 530 they were again stopped, this time for good. Some of the Huns stayed on in the Punjab, at the northwest corner of India, but they were soon absorbed in the population.

In 606, a man named Harsha became the king of a state near the modern Indian capital, Delhi. He seized most of the lands that had once belonged to the Guptas and imposed order on North India. Harsha proved to be an excellent ruler, ranking, with Chandragupta II, among the best in Indian history. He was also a remarkable man in other ways. Interested in the smallest details of government administration, he spent much of his time roaming about his empire on the back of an elephant, inspecting. Schools and universities flourished under his protection. He courted the friendship of scientists, scholars, writers and wrote several learned works himself.

THE CASTE SYSTEM

When Harsha died in 647, his empire collapsed. His was the last important native kingdom in India. After him, kings and nobles fought one another almost continuously. Throughout India, warlike dynasties rose and quickly fell. Meanwhile, Buddhism became more and more a set of empty rituals conducted by the Brahmins for their own benefit, until it lost all contact with the people.

Five centuries were to pass before north India was again united. During this time the ancient system of caste became more complicated than ever. Once there had been only four castes — the priests or Brahmins, the warriors, the farmers and storekeepers and the serfs. Gradually, thousands of small castes developed within the four groups. No one could change his caste or the work he was forced by birth to do. No one could marry outside his caste. This rigid social pattern cut people off from one another and blocked the exchange of ideas. In such an atmosphere, new ideas could hardly take root and grow. As a result, little good work was done in literature and the arts.

No invader appeared from the north to bring in new blood and new ways of doing things. Sea trade with foreign countries fell off. The peaceful contacts with China, which had stimulated Indian thought for centuries, dwindled to a mere trickle of traders and travelers.

In its increasing isolation, India became more and more self-satisfied. As one irritated foreign observer wrote: “The Hindus believe that there is no country but theirs, no kings like theirs, no religion like theirs, no sciences like theirs . . . If they traveled and mixed with other nations they would soon change their minds, for their ancestors were not so narrow-minded as the present generations.”

The great subcontinent was ripe for a change.