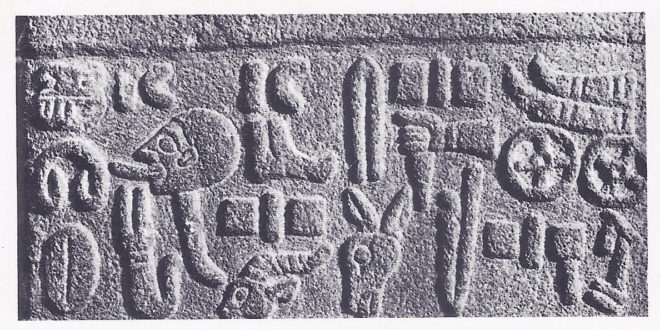

The vacuum left in Western Asia by the passage of the Sea Peoples was soon filled. New peoples infiltrated into the devastated areas and settled there. Some cities like Alalakh and Ugarit were never rebuilt; others rose again from their ashes. Tribes of Phrygians from Europe and their kin, the Mushki or Moschoi, divided the Anatolian plateau between them, but remnants of the Hittite peoples still continued to survive under their rule. Others, remaining outside the Phrygian orbit, retained their old traditions in the cities of southeastern Anatolia, the Taurus mountains and the plains of North Syria. Here they built temples to the old gods of the Hittite empire and the inscriptions in their palaces are written in hieroglyphic script, the ancient writing that had coexisted with cuneiform since its beginning in Anatolia. In many of these “Neo-Hittite” states, however, the ruling element was soon Semitic, for camel-riding tribesmen from the North Arabian desert moved into settled areas and took control of cities, setting up a series of political states. Once established, they flourished on commerce, acting as middlemen between the Mediterranean coast and the cities of Babylonia and Assyria. Competition, however, was to be their downfall: they proved incapable of combining. Their historical inscriptions celebrate victories over rivals, whereas a much greater danger threatened them from across the Euphrates.

Assyria Expands

The Assyrians, now welded into a mighty military machine of formidable efficiency, were bent on expansion. One after another, as the Assyrian armies swept westwards, the Aramaean states crumpled and were swallowed up; one after another the cities of North Syria, Carchemish and Arpad, Hamath and Damascus fell and Israel and Judah paid tribute. The wealthy coastal cities of Phoenicia bought their freedom for a time, but they too were occupied and by the seventh century Egypt herself was prostrate under the heel of Assyria. It was an empire such as the world had not seen before. The only kingdom to resist occupation, in spite of repeated campaigns, was the mountainous realm of Urartu, to the north of Assyria. Urartu’s capital on the shores of Lake Van was impregnable to the attacks of the Assyrian siege engines. The Urartians, distant relatives of the Hurrians, had developed in their hilly fastness a remarkable civilization of their own, about which more is now beginning to be known, as excavation on sites in south Russia and northeastern Turkey uncovers their temples and palaces. Long at loggerheads with the Assyria, who coveted their mineral resources, they eventually made a treaty with them. To Assyria, friendship with the Urartians had become desirable, for they were the last bulwark against a threat that now once more loomed terrifyingly large.

We have shown earlier how certain groups of nomads, some of them Indo-European in speech and custom, had poured over the mountains from the north and established themselves in Anatolia, Mesopotamia, Iran and northern India, but the steppelands of Central Asia continued to be a reservoir of nomadic peoples who periodically, in response to various pressures — famine maybe, or the impact of other, more distant migrations-invaded the civilized lands on their borders, from China in the east to Europe on the west. In about 1000 B.C. Indo-European groups began once move to overrun Persia from the direction of the Caucasus. Their bronze horse trappings and weapons are found in stone-built graves in the Luristan hills. Some were Iranian tribes, forerunners of the Medes and Persians whose fortunes we shall briefly relate. Other invaders from the Russian Steppes traveled more slowly and later, from about 800 B.C., nomadic groups known to classical writers as the Cimmerians, Thracians and Illyrians invaded the plains north of the Black Sea and the Danubian basin. Not long afterwards, a white-skinned horde of horse-riders known as the Yueh-Chi were troubling China.

The Scythian Onslaught

The Cimmerians who invaded Asia Minor in the eighth century B.C. were escaping, so Herodtus tells us, from the Scythians who were hard on their heels. About the Scythians we are well informal for a number of Greek writers describe their appearance and their customs and way of life. They were a short, bearded people who wore tunics and baggy trousers. Their covered wagons were drawn by oxen and these were their only habitations. They were brilliant horsemen, skillful archers, scalp-hunters, they practiced witchcraft, shamanism and drank from cups made from the skulls of their enemies.

They succeeded, as the Cimmerians had not, in bringing to an end the Phrygian kingdom in Asia Minor. For fifty or perhaps a hundred years, their advance was stemmed on the west by the armies of Lydia and to the south by those of Urartu and Assyria. Waves of Scythian onslaught beat in vain against the rocky strongholds of the armies of Van, but at last the kingdom of Urartu fell. At Karmir Blur, a rocky stronghold near the Russian border with Turkey, signs of a desperate last stand have been found: meals abandoned half-eaten, wine jars overturned, arrowheads of Scythian type embedded in the skeletons of those who had fallen in the arrests or on the battlements.

Medes and Persians

The Assyrians, too, were to succumb. In 612 B.C. the Scythians joined an alliance with two other of Assyria’s enemies, the Medes and the Babylonians; Nineveh fell and the empire was partitioned between the victors. It was, however, the more highly developed military power, the Medes, rather than the Mid Scythians, into whose hands the northern part of the empire fell, while Babylonia took over Arabia, Phoenicia and Palestine. We first hear of the Medes and Persians in the eighth century B.C., when both “Madai” and “Parsua” paid tribute to Assyria’s king Shalmaneser III. At this time the Medes were concentrated around the south of Lake Urmiah, in the north of Iran; later they moved south and made Ecbatana, the modern city now called Hamadan, their capital. Farther south, in Fars, the modern Shiraz district, a ing king of Parsua named Cyrus, a descendant of one Hakhamanish or Achaemenes, became a client of the last great king of Assyria, Ashurbanipal. After the fall of Nineveh, the Persians became vassals of the Median empire, but it was they and not the Medes, who were destined to create the first Iranian empire, far wider than that of Assyria. It is often called the Achaemenid empire, after the founder of the line. In 539 B.C. a second and greater Cyrus, who had already captured Ecbatana and united Medes and Persians under his rule, conquered Babylon.

This date was truly a milestone in history, for it marked the end of the long political dominance of the Mesopotamian powers and the shift of leadership; to Iran. Under its successive Achaemenid kings, Persian domination spread over the known world and into regions hitherto outside the ken of civilized peoples; not only the Fertile Crescent and Egypt, but the whole of the peninsula of Asia Minor as far as the Ionian coast was made subject and to the east huge territories including Bactria, the region of the Hindu Kush and even the Indus Valley, were made tributary. This empire, the greatest the world had yet known, continued until its overthrow, two centuries later, by the young and remarkable Macedonian adventurer, Alexander.

The Rise of Persia

The success of the Achaemenids was perhaps due in part to their freshness of outlook, their youthful energy and their freedom from the shackles of tradition. In part it may be ascribed to the bankruptcy and exhaustion of the ancient civilizations of the Near East, torn by internal discord and harassed by enemies from without, but largely it was due to the wise and liberal policy of the Achaemenid kings, a policy of adaptation and reconciliation whereby the old could be welded together with the new. The Persians respected local traditions, honoured the gods of their subject peoples and interfered as little as possible in the affairs of their subjects. Their liberal attitude is in keeping with the tone of moral enlightenment and ethical balance which characterizes their religious outlook.

For great though their political achievement was, it is in the realm of religion that the Achaemenids left their mark indelibly on the world. For this, one man is responsible, Zarathustra or Zoroaster as the Greeks called him. To him also is owed the earliest compositions of Persian literature, the Gathas, religious poems that were later incorporated into the sacred book known as the Avesta. We know very little of Zoroaster’s life. The Gathas, which record his utterances, are difficult to interpret. Even the very date of his birth is widely disputed. Many authorities consider that the prince at whose court he found protection and encouragement was the father of Darius the Great; others consider that he lived some centuries earlier, or else that, although he may have lived in .the sixth century, the effect of his teachings was not felt until much later,

The question of whether or not the Achaemenid kings of Persia were themselves followers of Zoroaster is a matter of debate, though it is certain that they upheld one of the essential tenets of Zoroaster’s faith: the belief in Ahura Mazda, the embodiment of goodness, wisdom and truth. Zoroastrian influence extended far beyond the frontiers of Iran; it had a profound effect on Judaism, especially in the realm of eschatology the concepts of the afterlife, of purgatory, judgment and resurrection and these ideas passed over into Christianity and became an integral part of orthodox Christian belief. In India today, Zoroastrianism continues as the faith of the relatively small but influential community of Parsees and in Iran there are still areas where the ancient faith is still followed and the ancient rites performed.

It has been said that most scholars believe the most likely date for Zoroaster’s birth is the early sixth century B.C., perhaps around 570, in the lifetime of the father of Darius. By a strange coincidence, within a few years, another great teacher was born whose religious doctrines, different though they were in many respects, were to have an equally profound effect on the lives of many millions. This was Gautama, the Buddha.