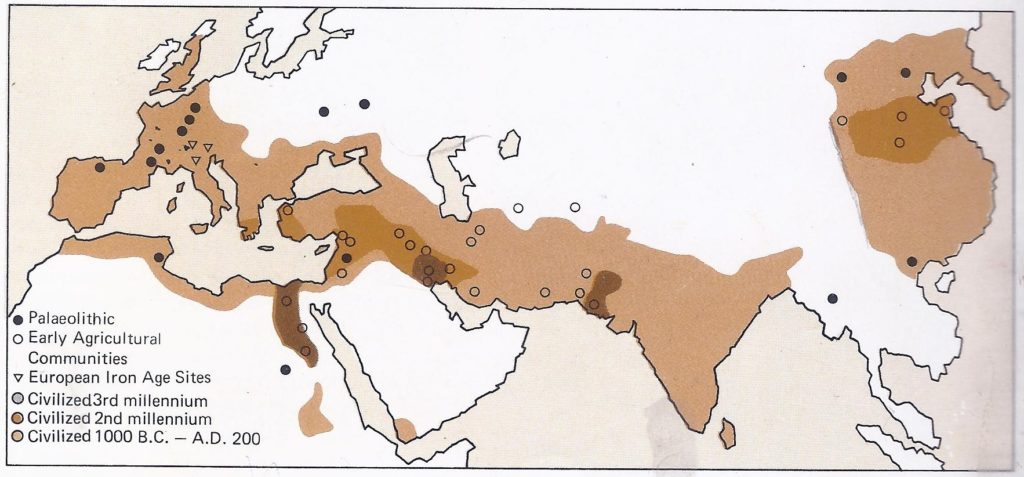

Early culture, between 3000 to 1750 BC, in Mesopotamia, the land between the rivers, another civilization is already far advanced.

The ancient Egyptians can be said to have been the first ancient people to create a national state. Another ancient people, however, can claim priority over the Egyptians in the invention of some of the arts of civilization and in the development of urban life. These were the inhabitants of the early culture of ancient Mesopotamia, now called Iraq, the land through which the Tigris and Euphrates, the Twin Rivers, flow. In the southern part of this land the inhabitants were of the early culture of Sumer. Excavations have shown that at a time when the Egyptians were still simple fishermen living in wattle and daub huts, using flint tools and storing their grain in baskets, there were people living in the valley of the Euphrates who already lived a life of some sophistication, in walled towns which (since this is a relative term only) we may call cities. They had built imposing towers and temples of mudbrick, ornamented with mosaic and fresco; and had achieved considerable technological mastery in stone-cutting, metallurgy and the potter’s craft. The most remarkable evidence of this urban early culture comes from Warka, about two hundred miles from the present head of the Persian Gulf, which was the site of ancient Uruk — the Biblical Erech. Similar remains of early culture, dating to the middle of the fourth millennium B. C., have been found at Ur, Nippur, Eridu, Lagash and many other sites in Sumer; also farther north at Mari, on the Euphrates near its junction with the Khabur and at Tell Brak on its headwaters.

Life in Sumer

Agriculture and dairy farming were the bases of life in Sumer. The alluvium brought down by the rivers is very fertile and the productivity of the land remarkable; barley and wheat were the staple crops whilst the date palm and vine were cultivated. Fish abounded and was an important source of food; so also were sheep and goats, of which there were many varieties. The rivers, whose annual flood brought life to the fields of the Sumerians, were also a constant threat to their safety. Tradition preserved the memory of a disastrous flood which had once all but wiped out mankind; the hero Ziusudra, who escaped in a boat of bitumen and reeds built at the behest of the god Enki, the watergod, was the prototype of Noah.

The Invention of Writing

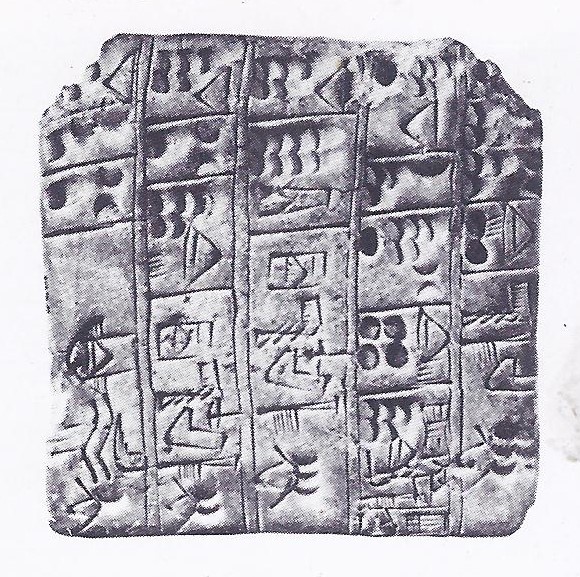

One of the greatest advances in the history of man was the invention, about 3500 B. C., of a system of writing. The earliest clay tablets are simple accounts — lists of objects, persons or animals, each depicted by a line drawing, or “pictogram,” followed by a series of numerical signs or numbers. They are little more, in fact, than tallies, inscribed on small square cushions of clay.

Gradually, however, the picture writing was stylized and the lines, jabbed for speed wit the slanting edge of a reed stylus, became wedge shaped or cuneiform. this writing system evolved to such an extent that abstract ideas could be expressed.

Sumerian Origins

The Sumerian language is quite different in structure and vocabulary from any other known language of the ancient world and attempts to derive the Sumerians from an original home in the Caucasus mountains or from the Iranian plateau, on linguistic grounds have so far failed. Nor does archaeology give us much help.

It has been suggested that the curious temple-tower characteristic of Sumerian cities the ziggurat, as it was called is evidence that the Sumerians once worshiped their gods on the tops of mountains. Perhaps many strands were interwoven to make the fabric of their civilization. There may have been a Semitic element in the population of Mesopotamia from early times certainly in the north at Mari, for the princes of Mari bore Semitic names, though they wore the sheepskin skirts and leather cloaks of the Sumerians and shared the same material civilization.

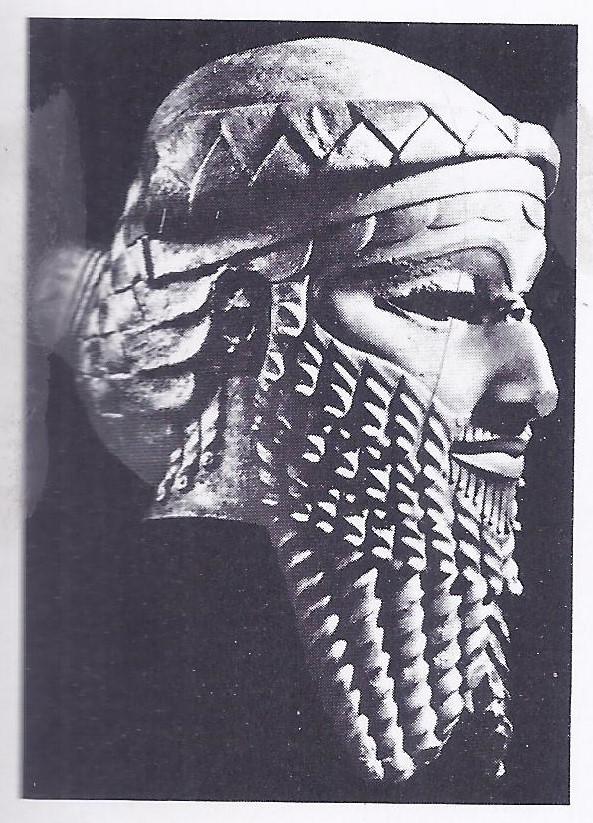

It was a Semite, a man called Sharrukin, or Sargon, who became cupbearer to the King of Kish (near Hillah) and finally seized power in that city. In a series of brilliant campaigns, Sargon wrested the hegemony of Sumer from the leading city of the time, Umma, establishing his new capital at Agade in Akkad, not far from Kish, in about 2370 B. C. Henceforward he was to rule as King of Sumer and Akkad. His successors claimed the title “King of the Four Quarters (of the World).” Both he and his grandson, Naram-Sin, led armies into North Syria and Anatolia, sources of copper, lead, silver and gold; they hewed conifers in the Amanus mountains and floated the logs down the Euphrates to build their palaces.

For the first time Mesopotamia was united under a single, strong administration and the Akkadian kings dominated the whole of western Asia. The ships of the merchants of Agade sailed southwards from the port of Ur, down the Persian Gulf to Tilmun, which is thought to be the Island of Bahrein and further south to the lands of Magan and Melukhkha. Magan, which may be the Makran coast of Persia, perhaps included also the coast of Oman on the other side of the Straits, a land rich in copper and stone. For Magan furnished the Sumerians with the hard black stone for their statues, copper ore and lumps of lapis lazuli, the valuable blue stone used in inlay and jewelry, which came many hundreds of miles from the mines in Afghanistan. Melukhkha lay even farther away: many scholars believe this is the Sumerian name for early culture in India.

Indus Valley Civilization

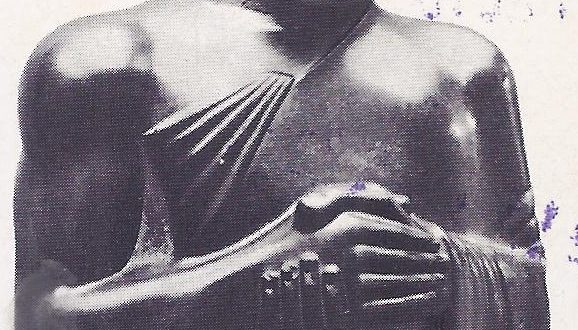

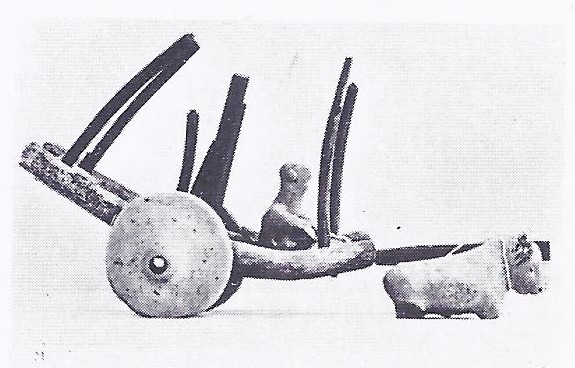

In the northwest corner of the continent of India at this time a great civilization had grown up in the basin of the Indus River. Its two chief cities, called today Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa, lay some five hundred miles apart. Each was a masterpiece of town-planning, with rectangular blocks of houses divided one from the other by a crisscross of streets broad enough to take the solid-wheeled ox-carts. Houses and public buildings were of burnt brick — a necessity in a land of monsoon rain, whereas unbaked brick sufficed in Sumer and there was an elaborate and skillfully planned drainage system to carry away both sewage and rainwater. A lot has been said of the early culture of the Indus Valley Civilization, or Harappan Culture, as it is sometimes called. suffice it to say that ample evidence has been discovered of the existence at this time of Indian ports and trading stations in the Gulf of Cambay and on the Pakistan coast north of Karachi and even on the south coast of Makran itself.

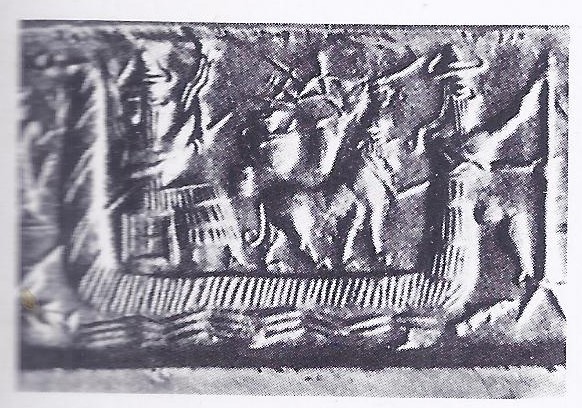

Seals and other objects of Indus Valley workmanship found by excavators on Mesopotamian sites of the Akkadian period are evidence of contact between Sumer and the Indus Valley. Some scholars are inclined to think that the civilization of Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa was either directly based on, or else inspired by, that of Sumer at an earlier period. There are, however, many essential differences between the two and the pictographic script of the Indus Valley owes nothing, so far as the scholars can see (the language is unknown, for it is as yet undeciphered), to the cuneiform of Mesopotamia or its pictographic prototype. Moreover, the animals on the beautifully cut steatite seals are entirely those of the Indian fauna — the buffalo, the elephant and the rhinocerus, none of which was known in Sumer. While it cannot be denied that there was contact, either direct or indirect, between the two areas — perhaps over a long period, till the time of the First Dynasty of Babylon — the inspiration behind the civilization of the Indus Valley has yet to be traced.

Defeat of Naram-Sin

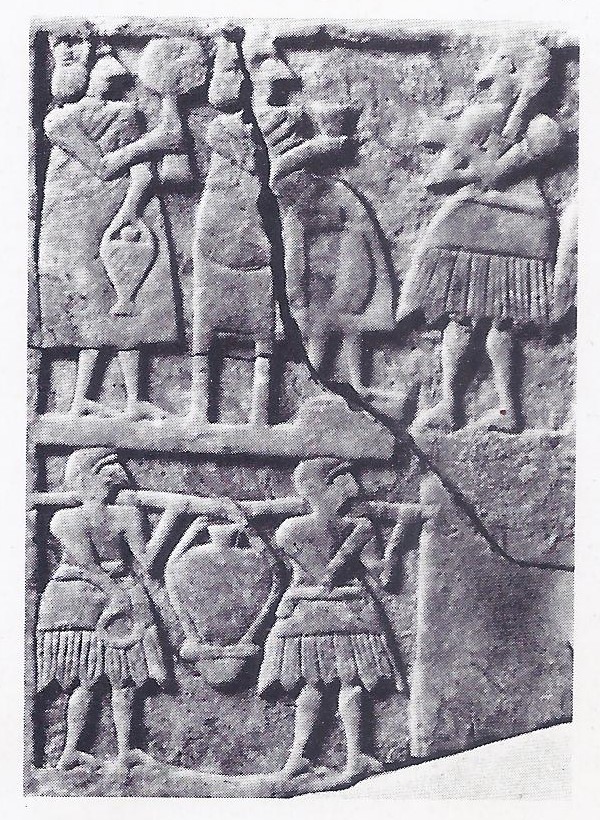

In Mesopotamia, Sumerian was gradually replaced in official documents by Semitic Akkadian, though Sumerian was retained in the temples. The administration of the kingdom was centraized and the old citizen army of the Sumerian states was replaced by a professionalbody trained in mountain warfare. The need for such an army was a real one for enemies now began to press in upon the kingdom of Agade. Naram-Sin himself met with defeat from a coalition of mountain Chieftains in the north of his realm and though his successors managed for a time to stave of disaster, in about 2200 B. C. the Gutians, invaders from the Zagros mountains to the northeast of Iraq, captured Agade and took over the country.

In the south of the country, however, the old Sumerian cities seem to have been little affected by Gutian rule and it was in these ancient centers of civilization, Uruk and Ur, that the people finally combined forces to drive out the invaders. Under the able rule of the Third Dynasty of Ur, the country was reunited and prosperity returned. Elam was made subject and a profitable trade with the interior of Iran was thereby secured. Ships sailed again down the Persian Gulf, and among the treasures they brought back were carved ivory figures and pearls. This was the golden age of Sumerian civilization. Temples were rebuilt on a grander scale than ever before, among them was the great ziggurat at Ur, which became a landmark for miles around. Literature flourished under royal patronage and a system of law was codified.

The significance of Sumerian early culture lies not only in its antiquity and intrinsic achievement, but in that it was adopted, and adapted, by the Akkadians and their successors, the Babylonians and Assyrians. They adopted the pantheon of Sumerian gods and adjusted it to accommodate their own gods of desert and sky. They took over Sumerian script, adapting it to their own language and kept Sumerian as the language of liturgy.

Thus after the collapse of the Ur dynasty, the ancient traditions continued. After a period of confusion, the city-states regrouped under new leaders: these were the Amorites, a Semitic people from the west who moved into the cities of Mesopotamia and gradually took control of many of them. Babylon was the seat of one of these Amorite dynasties and Hammurabi its king.

An able warrior as well as a capable administrator, Hammurabi inherited from his Amorite predecessors a modest kingdom centered around the small town called Babil, or Babylon. Early in his reign he achieved some success, but he had to wait thirty years for his great victories. If one considers the significance of his reign in terms of human achievement, Hammurabi’s name is connected with one remarkable document. This document and its far-reaching significance is greatly written about in history.