We have seen that after the fall of Babylon in 1530 B. C. and the collapse of the Amorite kingdoms of the Euphrates area and North Syria, new peoples of different races entered the area and a new pattern of settlement developed. In the sixteenth and fifteenth centuries, the focus of our interest leaves the valley of the Two Rivers and is concentrated rather on Syria and Palestine and in particular on the new kingdoms which, with a population now partly Semitic (or “Canaanite,” the Biblical writers’ term) and partly Hurrian and often with an Indo-European aristocracy, were emerging as political entities. Their history is bound up with that of the rulers of Egypt, which now for the first time becomes an imperial power with widespread influence and far-reaching commerce.

Egypt in the Lebanon

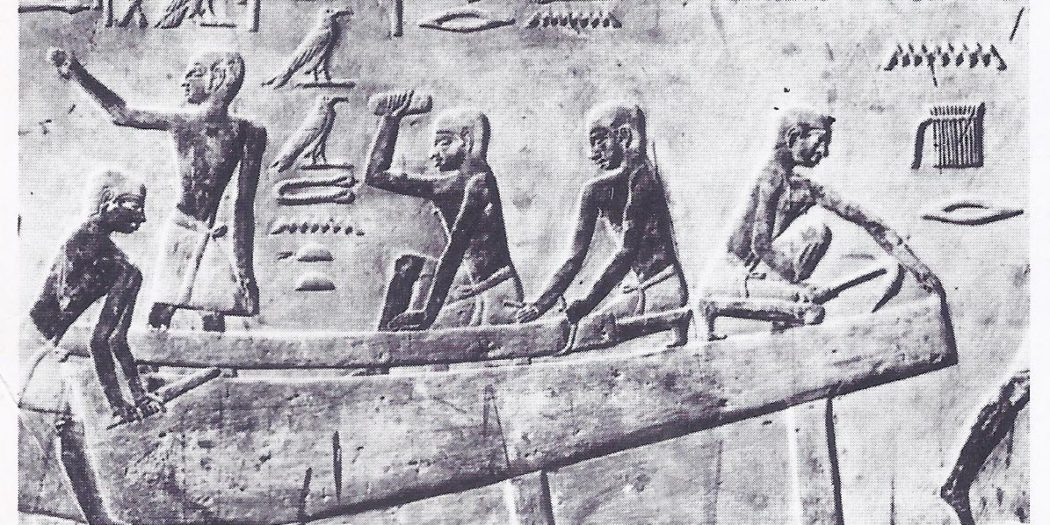

The coastal plain of the Levant, later known as Phoenicia and the Syrian hinterland as far as the Beqa, that is to say, the valley dividing the mountain ranges of Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon, had for some centuries past been in contact with the civilization of the Nile Valley. Originally, Egyptian influence had been confined to Byblos, a well-favoured port north of the modern city of Beirut and the forested slopes behind; from here, since the earliest historic period and perhaps even earlier, the Egyptians had brought the long timbers of pine and cedar they needed for shipbuilding, which were conspicuously lacking in the valley of the Nile. Their interest had spread during the Middle Kingdom to include other parts of the Lebanon with which they established a trading relationship; in Palestine they may even have achieved some kind of military domination during the Twelfth Dynasty.

Egyptian influence had declined, however, as soon as the strong hand of the Twelfth Dynasty Pharaohs was withdrawn. Egyptian armies no longer marched north and when the centralized control of the Pharaoh at last broke down, the country was split into principalities, even the sea link with Byblos was broken. The forts that had guarded the eastern frontier ceased to be effective. Bedouin bands infiltrated across the border, the trickle became a stream and the small kingdom set up in the eastern Delta by these desert sheikhs (or Hyksos, the “shepherd kings” of Greek tradition) grew in size till the Hyksos bid fair to take over the whole country. For something over a century, between approximately 1720 and 1600 B.C., the valley of the Nile was parceled out between Asiatic Hyksos in the north, native Egyptians in Upper Egypt and Nubian princes to the south, beyond the first cataract of the Nile. It took an almost superhuman effort for a family of local grandees in the Theban area, rallying patriotic support, to drive out the foreigners and restore unified control over the whole country. On the crest of a wave of military success, these first Pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty went on to win back Nubia (which in the Twelfth Dynasty they had controlled as far as the second cataract) and to carry their arms farther into Africa. At the same time, they started northwards on the military road that was to lead them to the conquest of Syria and Palestine and to bring them face to face with the armies of both the Hurrians and at length, the Hittites.

The confrontation was not, it seems, immediate. Tuthmosis I appears to have marched unimpeded to the Euphrates but after he withdrew, most of North Syria and even eastern Cilicia came under the overlordship of the Mitannian kings. The greatest of these, Shaushatar, controlled Assyria too and his authority reached as far as Kirkuk, east of the Tigris. Fifty years after Tuthmosis surprising foray, the challenge was renewed and this time the Egyptian army found its way barred. The Mitannians had rallied to their aid the rulers of many of the small city-states of Syria many of them now ruled by Hurrians and Tuthmosis III, the greatest of Egypt’s warrior kings, had to fight every inch of the way. In a series of seventeen campaigns from 1480 to 1454. B.C., he again and again fought in Retenu (the Egyptian name for Syria/Palestine), capturing cities, devastating the countryside, punishing rebel towns that threw out their garisons and at least once putting to flight the main force of the Mitannian army. By the end of his reign he had driven Shaushazar from North Syria and set his frontier at the Euphrates.

Colonial Administration in Egypt

Tuthmosis III must be credited, with the organization of a rudimentary colonial administration. Native rulers were left in charge of their own city-states. as vassals bound by solemn oath of fealty to their overlord the Pharaoh. They were bound to pay heavy war indemnity and to furnish annual tribute assessed in kind: large quantities of copper, gold and other metals; cattle and flocks; agricultural produce, honey, wine and oil. Their sons were taken to Egypt to serve as hostages, for their good behavior and also to be given an Egyptian education to fit them for rule when their turn came. The daughters of vassals entered the Pharaoh’s harem. Egyptian garrisons were left at strategic points, fortresses were built and Syrian harbours, supplied by local labour, served as supply bases.

Heyday of the Egyptian Empire

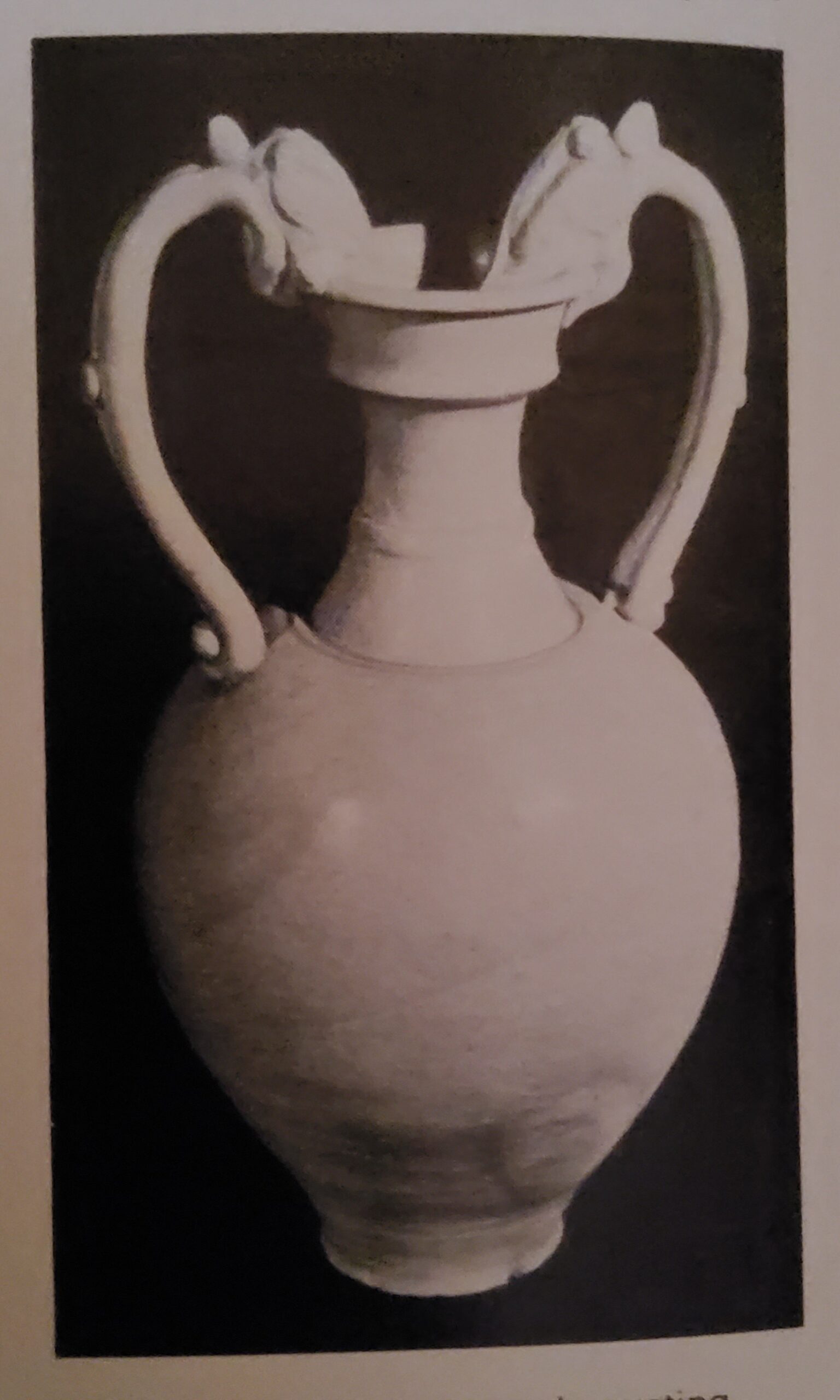

This was a time of great prosperity for Egypt. In the heyday of the Egyptian empire, during the reigns of Amenophis II, his son Tuthmosis IV and his grandson Amenophis III, sometimes called the Magnificent, wealth poured into the coffers of Egypt. The gold mines of Nubia were exploited to the full and caravans brought to Pharaoh’s treasury the exotic products of the Sudan — ivory and ebony, panther skins, frankincense and myrrh. Tribute poured in from Retenu and valuable presents were sent by the rulers of the Near East, the Cassite kings of Babylonia, the Assyrians, the Mitannians (now bound in friendship to Egypt by a treaty of alliance), the rulers of Cyprus and of Crete and the Aegean islands. In the tombs at Thebes of great officials — the grand viziers, the treasurers and viceros whose duty and privilege it was to receive foreign envoys and accept their gifts — many paintings are preserved, sometimes still in their original bright colours depicting these ceremonial occasions. Here the ruler of Tunip can be seen, carrying on his arm his little son who is to be brought up Egypt; with him are Syrians, their brightly patterned tunics contrasting with the flowing white garments of the Egyptians. Here too are Mitannians — portly, bearded figures with voluminous robes wound round their bodies; and men in Mycenaean dress, identified as from “the isles in the midst of the Great Green (sea),” with bulls heads drinking cups and other Aegean vessels familiar from the excavations of Heinrich Schliemann, Sir Arthur Evans and others in Crete and on the mainland of Greece. In some tombs, of the age of Tuthmosis III, the Keftiu or Cretans depicted with hair curling over their foreheads, bare chests and short loincloths, are certainly to be identified with the Minoans; they too we must imagine, came to marvel at the magnificence of Pharaoh and to gaze in awe at his huge temples and vast palaces, glittering with gold and precious stones, so different in concept and style from their own cool, frescoed halls.

The Apostate Pharaoh

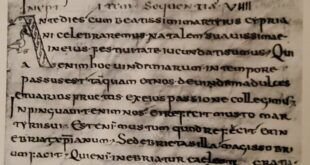

At the height of the empire’s prosperity, a sudden internal crisis developed, which was to distract Egypt’s attention for a time and to rule out all possibility of further conquest abroad. It was a strange crisis, one of the most curious episodes in the history of the ancient world and we do not yet completely understand its cause or its effects. It arose from the personality of one individual — the son and heir of Amenophis III, who bore the same name and who succeeded his father in about 1380 B. C. Around the figure of this king controversy has raged. Was he genius or madman? Was his religious reform prompted by monotheistic zeal, poetic inspiration or political astuteness? In opposition to the powerful and wealthy priesthood of the state cult of the god Amun, Amenophis IV restored the ancient cult of the sun-god, but gave it new expression in the form of the solar disc whose rays, ending in little hands, shed blessing and light upon the king and queen. He insisted that the worship of this sun-god, the Aton, should be exclusive and other cults were either proscribe or neglected. He changed his name to Akhenaton, “pleasing to Atom” and moved to a new capital at Tell el Amarna, which he named “The Horizon of Aton.” Here he and his wife Nefertiti, whose beauty is familiar even to those who know nothing of her history, were able to worship their new god and live a life of domestic bliss (or so the relief sculptures in the tombs at Amarna would have us believe) with their six daughters.

In the hymns which were written in praise of the Aton, which many people think he himself composed, there is great emphasis on truth and beauty, emphasis on the universal nature of the sun’s domain:

Thou appearest in beauty on the horizon of heaven,

O living Aton, the beginning of life!

When thou risest on the eastern horizon,

Thou fillest the earth with thy beauty,

Thou art gracious, great, glistening, high over every land,

Thy rays encompass the earth to the bounds of all that thou hast made . . .

The phraseology of this hymn has been compared with one of the Biblical psalms (104) and Akhenaton’s reforms have been regarded by some as foreshadowing and perhaps indirectly influencing the monotheism of the people of Israel. However this may be, he did not succeed in winning over the people of Egypt and after his death, the priests of Amun were again able to assert their influence. The young king Tutankhamen, who had been born into the Atom faith as Tutankhaton, changed his name, while still a child, returned to Thebes, restored the neglected temples and reinstated Amun as the state god. Within a few years of Akhenaton’s death, his memory was execrated and his capital razed. The later authority of Egypt abroad suffered during this unhappy interlude and the Ramesside kings restored the prestige of Egypt in Syria.