As the political state evolved, the problem of its administration evolved too. The territory ruled over by Hammurabi of Babylon was composed not simply of two adjacent areas with similar characteristics — as in Narmer’s Egypt — but of former independent states with very different traditions. Hammurabi had extended his territory by conquest, but as overlord he proved a conscientious ruler, dedicated to reform, and possibly the greatest tribute paid to him by his subjects was the comment, preserved in the chronicles of the country: “He established justice in the land.” Inscribed on a stone, the memorial of his justice was providentially preserved for all time, despite its being carried of to Susa by an Elamite king early in the twelfth century B.C. Regardless of the fact that Hammurabi’s immediate successors were unable to hold on to the territory he had won, his legacy to mankind constitutes a momentous milestone in the progress of human achievement.

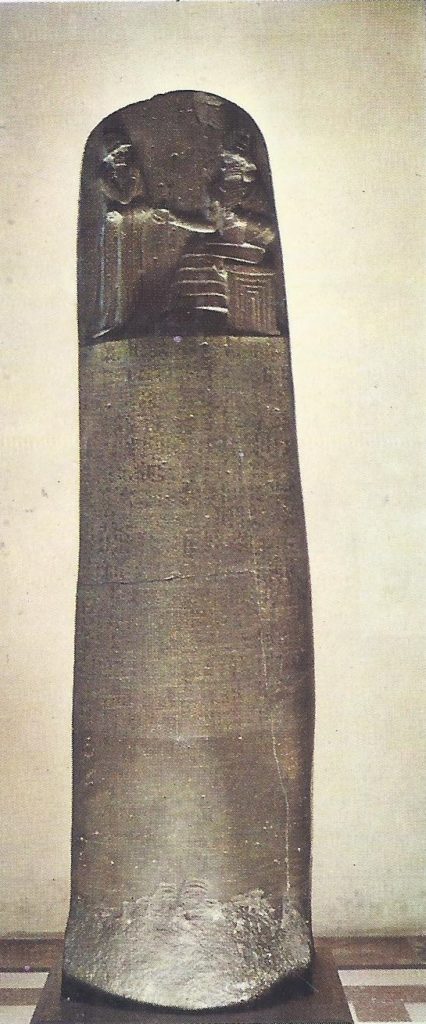

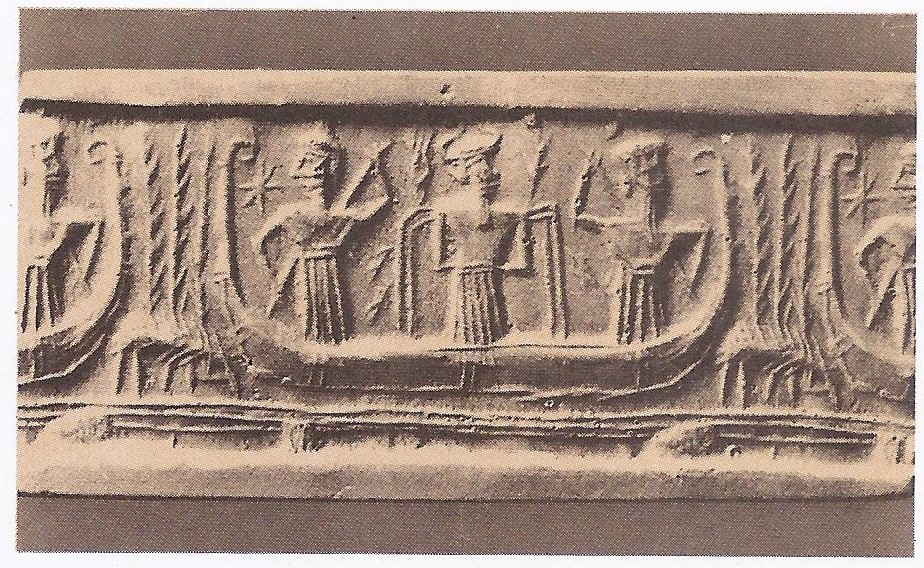

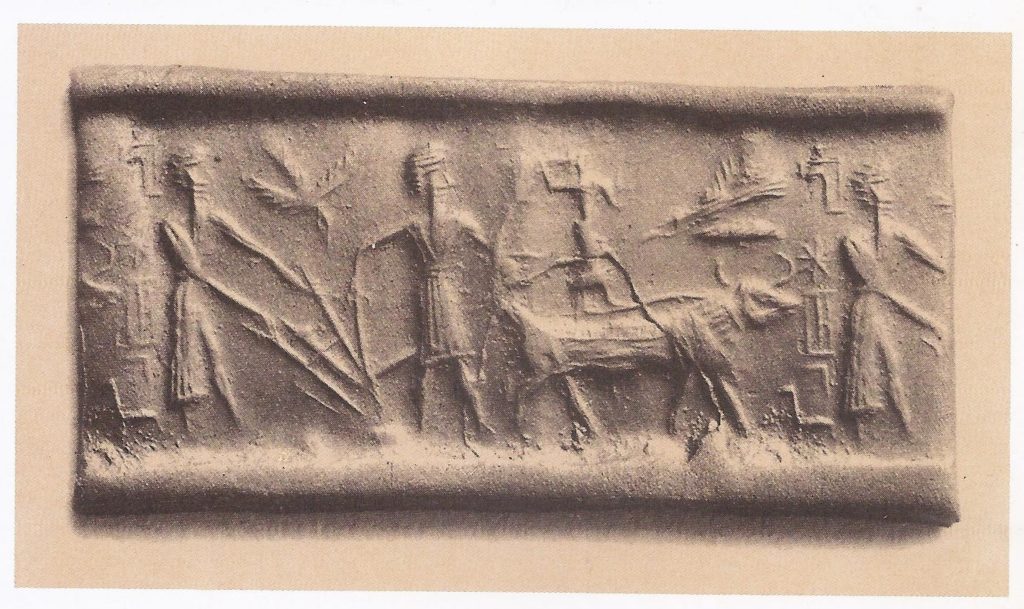

Sometime toward the end of his reign, the great Babylonian king Hammurabi (c. 1792 – 1750 BC) inscribed a code of “laws” on a tall stele of hard stone. It was neither the first nor the last document of its type in Mesopotamia: at least half a dozen similar codes are known, of which the oldest dates from the end of the third millennium, but none of them so deserves to be considered the classic of its kind; no other is so broad in its scope and of such intellectual and literary perfection.

The Code of Hammurabi, in fact, provides both a brief history of and a triumphant monument to, his reign. It is only toward the end of his life that a monarch feels the need to draw up an honours list of his successes and to give a summary of his experience and wisdom in order to inspire emulation as well as admiration. We know that the Babylonian empire as it appears in this code existed only during the great king’s final years. In the prologue to the code, Hammurabi mentions victories that he did not win until the thirty-fifth or even the thirty-eighth year of his forty-year reign. It is because that reign marks one of the culminating points in the history of ancient Mesopotamia, a civilization that lasted for at least three or four thousand years, that the code is so important as documentary evidence.

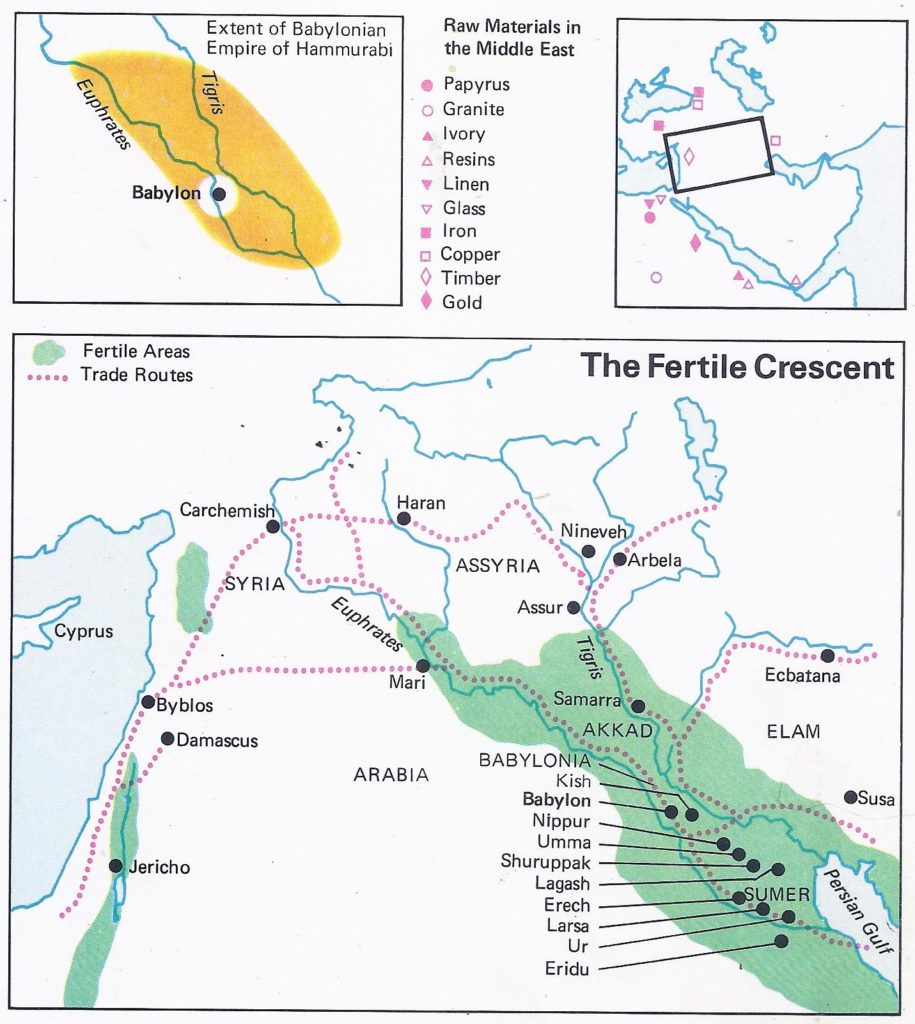

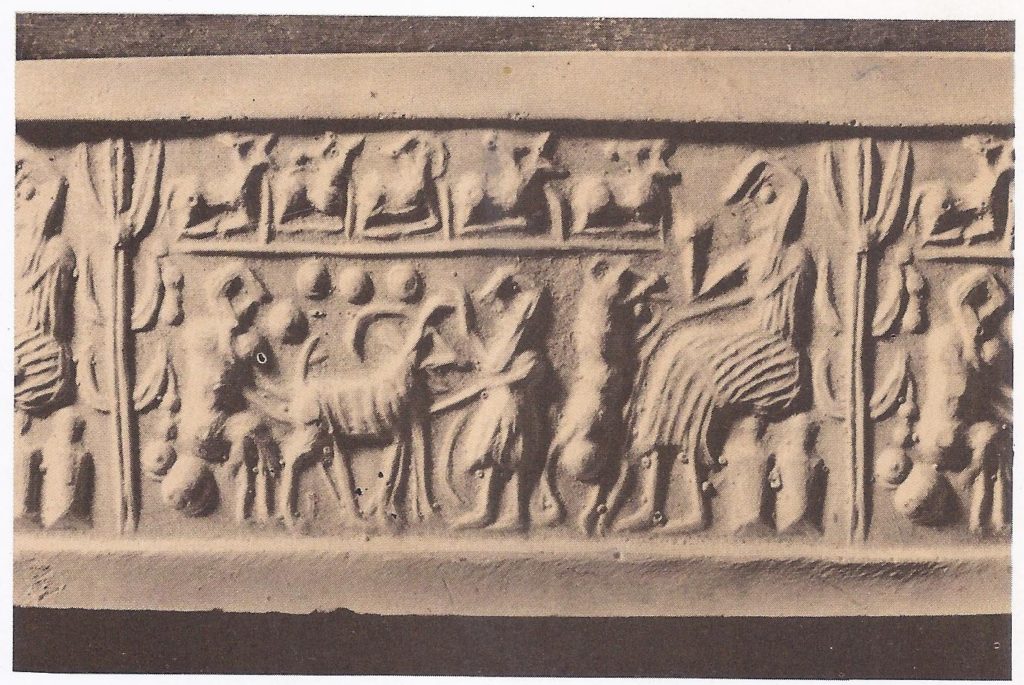

In the 1,500 years before Hammurabi’s reign, the “Land Between the Two Rivers” and above all the southern part of that territory, between present-day Baghdad and the Persian Gulf, had become the location of what one can call, compared with other minor prehistoric cultures, the oldest civilization in the world. Mesopotamian society was based on the systematic exploitation of land. The soil was cultivated intensively and its natural productivity, already considerable, was increased by the establishment of a great system of canals that ensured effective irrigation. In those areas that had not been taken for agriculture or the cultivation of palm trees, stock raising flourished, chiefly sheep and goats but also donkeys, cattle, pigs and other livestock. This work was carried out by the greater part of the population, both urban and rural. Its administration led to the establishment of a body of highly specialized civil servants, who preferred to live in the city near the palace and the temples; for it was there that the real rulers, the gods and their representative the king, had their headquarters.

The earth and all its produce belonged to the gods, as did the workers, who were their servants. Hence the harvest and the crops and the produce from herds (notably wool and skins) were brought for sale to the temples and stored in their warehouses. Once enough had been redistributed to meet the requirements of all citizens, according to their social standing, the rest was used as capital and as credit for huge commercial enterprises.

Since earliest times trade had been conducted with all the surrounding countries and even farther afield — from the Lebanon and Asia Minor to Persia, both along the coast and in the mountainous interior and as far as the western borders of India. Trade was vital to Mesopotamia because although it had a surplus of grain and animal products, it completely lacked certain raw materials that were necessary for civilized life. The soil provided only clay, bitumen and reeds; there was no timber whatever, no stone and no metal, although technicians had developed since at least the fourth millennium a technique of bronze work. Imported materials were worked by a host of skilled, often highly artistic craftsmen, who provided not only tools for farmers and stock breeders but also furnishings and works of art for the temples and palaces. These finished goods often found their way abroad as exports. One can see from this how well organized, how active and expanding the Mesopotamian economy was and how systematized and orderly was its society.

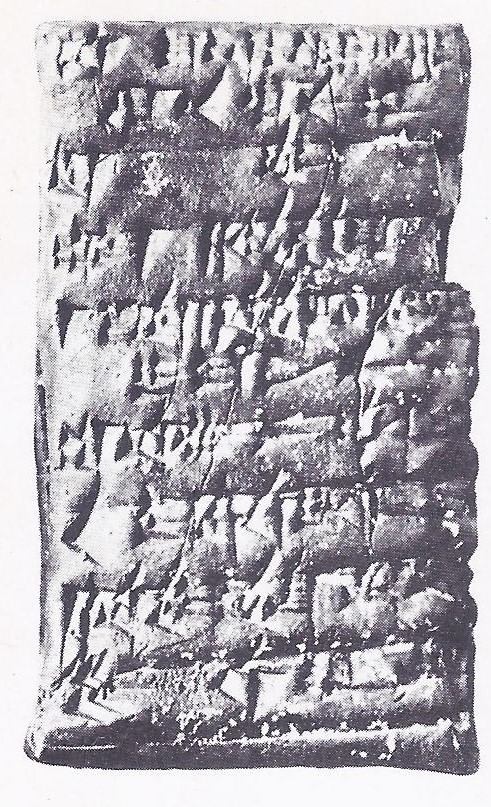

The vast amount of accountancy that such operations entailed had been considerably simplified about 2800 B.C. by what was virtually a stroke of genius: the invention of a system of writing. The system was still very complicated and was to remain so for a long period. Only specialists could understand and operate it, but they were to create the environment for the development of a truly intellectual culture. This writing was first used exclusively for keeping the accountancy records of the temples, but it was soon simplified, made more flexible and was then used for the compilation of dictionaries of signs and words, comprising all the symbols. Next it was used to record the deeds and exploits of kings. religious rites and myths that the philosophers and theologians of the time had constructed to explain the great eternal problems of human existence and destiny. Finally, it was used to express a certain number of scientific ideas and theories, the result of persistent observation and a profound desire to see the universe as orderly according to a particular perspective: divination, mathematics, medicine and jurisprudence.

Hammurabi Brings Order to his Kingdom

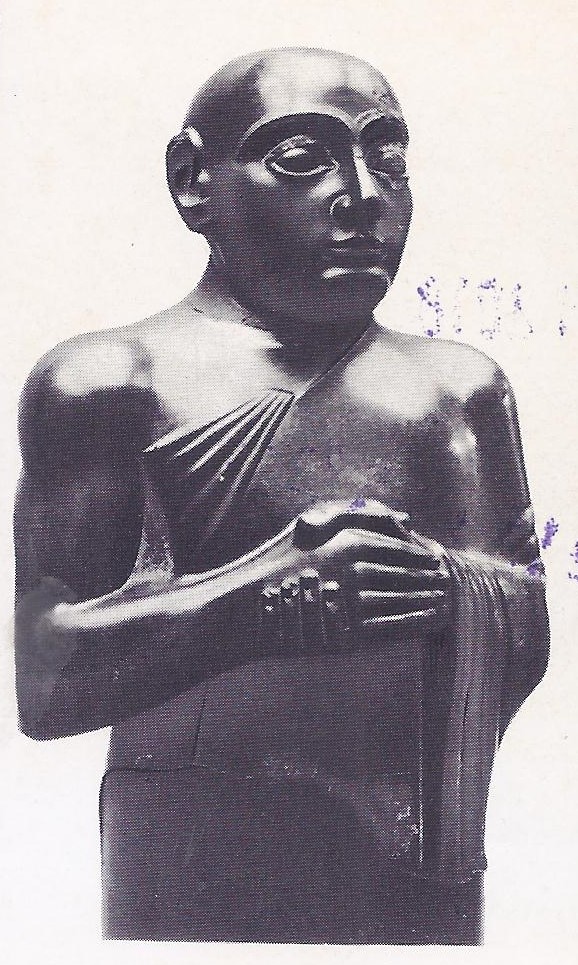

This high degree of civilization, already established by the third millennium, was the product of a mixed population, of which the major element and the most easy for us to identify were Semites and Sumerians. The former belonged to an ineradicable race of semi-nomadic shepherds who since the dawn of history have lived on the fringes of the great Syrian and Arabian deserts; and of whom a certain number have always been attracted by town life and have settled there. The Sumerians whose provenance is unknown but who probably arrived from the east or the southeast by the fourth millennium at the latest, seem to have severed all ties with their former home and their kinsmen. In Mesopotamia they never received that infusion of new blood that has perpetually nourished and strengthened the Semitic part of the population. Consequently, while in the first half of Mesopotamian history, up to the end of the third millennium, the Sumerians appear to be the active inventive and creative force in the development of civilization and at first more important in the political field, they were to find themselves gradually supplanted by the Semites.

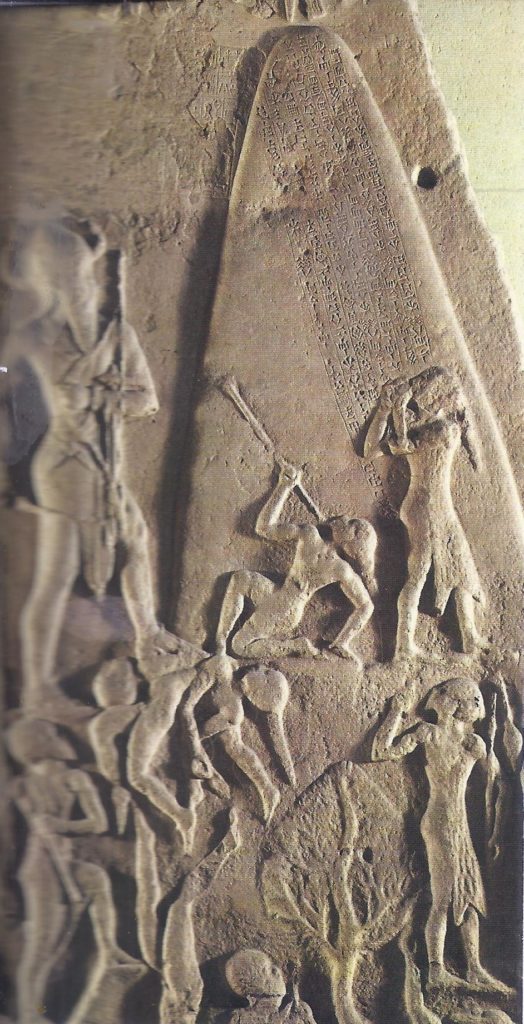

Politically, the country was divided into a certain number of small states, each grouped around a city, with a majority of Semites in the north. These city-states sometimes allied with each other, sometimes fought against each other and were sometimes combined into larger kingdoms by the predominance of one or other among them. By the third millennium it was the Semites who seemed to have the advantage of the biggest alliances. First, at an early stage, around the city of Kish and second, toward 2350 B. C. and for the following century and a half, around the city of Agade. At the beginning of the second millennium another Semitic dynasty, which seems to have been dominated by immigrants from the west, made Babylon their seat of power for three centuries (about 1900 – 1600 B. C.). This gave the greatest of their kings the opportunity to create a third Semitic Empire, displacing the Sumerians — who were this time completely absorbed and wiped forever of the map — and giving a special brilliance to the ancient civilization that had continued to expand and thrive for almost 2,000 years. This king was Hammurabi, whose “code” thus marked an achievement and a peak of civilization never before attained.

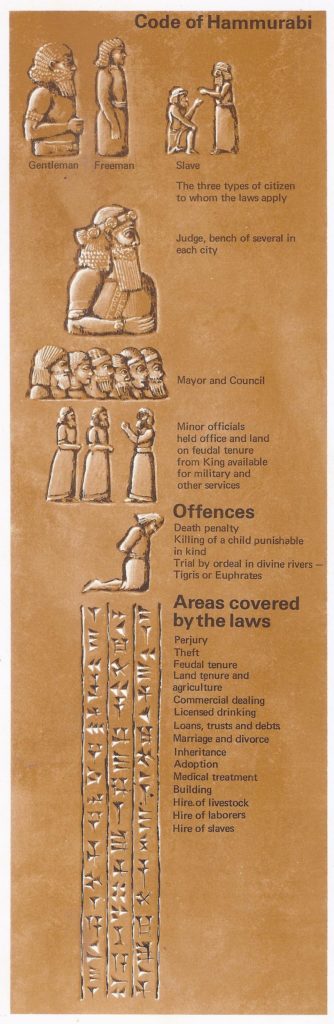

in this diagram.

Hammurabi’s impressive work — some 3,500 lines of ceneiform characters — is divided into three parts. There is a central section written in straight-forward, clear, unadorned prose. This section is framed by a prologue of three hundred lines and an epilogue of five hundred, which are sublime and lyrical in tone. with a choice of words and turns of phrase like poetry.

It is from the central part that the monument derives its name of “code,” which was bestowed upon it by its first decipherers. This section contains a series of regulations — 282 in all — that cover many secular activities. Some of these regulations concern crimes and their punishment: If a man has brought an accusation of murder against another without being able to produce proof — the accuser shall be put to death.

Others are related to administrative problems, such as the proper conduct of business affairs:

If a man of business has entrusted to a shopkeeper either grain or wool or oil or any other merchandise to sell retail — once the sale has taken place and the purchase money has been accounted for, then the shopkeeper shall transmit it to the businessman, but shall receive from him a sealed document in evidence of the sum which has been remitted.

A listing of the subjects covered shows the range of these regulations. They concern false witness, theft, royal fiefs (lands allotted by the sovereign to members of his entourage, on condition that they share with him the produce), husbandry, town planning, commerce, deposits and pledges, marriage, divorce, second wives, the joint responsibility of husbands and wives for debts, preparations for marriage, the disposal of assets after the death of a spouse or parent, certain particular cases like the marriage of widows or priestesses, adoption, wet-nursing, assault and injuries, regulations for certain occupations, both professional, menial and slavery.

Not all aspects of communal life appear in this list: for instance there is no reference to taxation.

Furthermore, when one looks at the code more closely the various paragraphs are all so concerned with specific and individual cases that it is impossible to describe them as “laws” in the proper sense of the word — that is to say, truly abstract and universal propositions. For example in the first paragraph quoted earlier, the question of false accusation on a capital charge relates only to murder, whereas there are numerous other possible examples like treason and sacrilege which should have been included for consideration. In the second paragraph quoted, the need for scrupulous and documented accounts should surely extend to many business dealings other than the specific one between the man of business and his agent.

It is therefore a mistake to refer to a “code,” at any rate if we mean to use the word in its true sense of a compilation of the entire legislation of a country and of a period. We are dealing rather with a collection of judgments originally pronounced to resolve actual cases and subsequently classified into a sort of treatise on jurisprudence, illustrated by examples. We must realize that the ancient Mesopotamians were as yet incapable of formulating abstract and truly universal principles, i.e. laws. They chose to instruct in methods of ordering society by formulating examples from a sufficiently large and typical selection of actual cases — in the way that we still teach our children grammar and arithmetic. The Code of Hammurabi is, then, both a manual on the art of judgment and a treatise on jurisprudence.

The prologue and epilogue enable us to understand better the significance that its author intended this imposing work to have. In the prologue Hammurabi confides to us his concept of himself and his role: he portrays himself as appointed by the gods to exercise royal power over his people and he flatters himself that he has accomplished this great duty to perfection:

When Anu the Sublime, King of the gods together with Enlil, Lord of the sky and of the earth, the master of destiny of peoples, had bestowed upon Marduk, the eldest son of Enki, supreme power over all peoples an had enabled him to prevail over all the other gods, when they had pronounced the majestic name of Babylon and decreed the extension of its power over the whole universe and the establishment of an eternal kingdom, based on foundations as immovable as those of the sky and the earth, then Anu and Enlil also pronounced my own name, Hammurabi, devout prince and worshipper of the gods, so that I might bring order to my people; so that I might free them from evil and wicked men, that I should defend the weak from the oppression of the the mighty and that I might rise like the sun over men and cast my light over the whole country.

Farming and Commerce Thrive under Hammurabi

In order to prove his success, the sovereign then enumerates his great achievements, in both foreign affairs and internal politics. The list of the former is shorter and less detailed: it recalls how one after the other he had subdued and united in a vast empire centered on Babylon all the formerly autonomous cities that had made up Mesopotamia.

However, in Hammurabi’s own eyes his most important achievement, the one most noble and the most welcome to the gods, was as an administrator who had kept his country in order and hence in a state of well-being and prosperity. This is why 282 articles, which were not only to immortalize his decisions and wise maxims, but also to demonstrate his real knowledge of law and his genuine gift of judgment.

Then after this lengthy catalogue, the sovereign the sovereign insists in the epilogue on the high ideals he has devoted to his divine mission. He presents himself as a model king and hands down his conduct, his experience and his knowledge as a source of instruction and inspiration for every sovereign worthy of the name who might come after him:

If any of my successors possesses the necessary understanding to keep the country in order, then let him pay attention to what I have engraved on my stele, for this will explain to him the course and the conduct to pursue by reminding him of the judgments which I have made for my people and the decisions which I have given them. In this way he will succeed in keeping his subjects in order, give them judgments and decisions, eradicate evil and wicked men from their midst and so achieve the well-being the people! Yes, it is me, Hammurabi, the just king, upon whom the god Shamash has bestowed the understanding of justice!

Laws for a Thriving Civilization

After the end of the Hammurabi dynasty the political balance was profoundly altered: henceforth, the struggle for supremacy was between the Semites of the south of the country around Babylon, and those of the north, first around Assur and then around Nineveh. They were to contend for power for at least a thousand years to come, until Mesopotamia passed under the domination, first of Persia (539 B.C.) and then of Greece (330 B. C.). About 1200 B.C. the Elamite king Shutruknahhunte, who had come to conquer and destroy Babylon, carried off the stele on which the code was inscribed to his capital, Susa, as a trophy of war.

Here archaeologists found it 3,000 years later, broken in three pieces and partly damaged. As a work of literature and learning, however, this same code was to last right up to the end of the history of ancient Mesopotamia, continually studied, re-read and recopied as one of the immortal classics of literary and intellectual achievement produced by this ancient civilization.

The Code of Hammurabi not only translates into clear language, with a precision of detail and an often remarkable exactitude, the principal institutions, the structure of the hierarchy and society, the administrative machinery and the economic mechanism of the great civilization of ancient Mesopotamia. It also conveys Mesopotamia’s quintessential spirit: the supreme importance of the gods and their decisions to everything that happens here below; the nobility and importance of the monarchy; the ideals of order and justice that must govern society and inspire the ruling class; and a preoccupation with scientific analysis, order and clarity.

For all these reasons, the code is a significant milestone in that ancient heritage built up over thousands of years by our far-off ancestors on the banks of the Euphrates and the Tigris, a heritage that fed two sources of our own civilization. Israel and Greece.