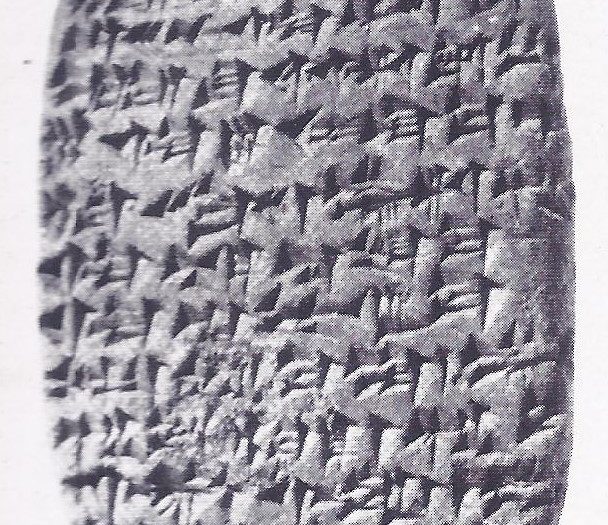

Palestine was possessed by Egypt. In the year 1887 an Egyptian peasant, digging in the ruins of an ancient city on the banks of the Nile, came across some baked clay tablets impressed with cuneiform writing. In due course these tablets came into the hands of dealers and eventually their importance realized. The city had once been the capital of Egypt, for a brief time in the early fourteenth century B.C. and the tablets had come from the record office of the palace; they were letters, part of the files of the Foreign office, the correspondence of the potentates and princes of the Near East with their ally, or in some cases their overlord, the Pharaoh of Egypt. They are written in Akkadian: the language of diplomacy in this age, as it had been in the time of the Mari letters and we must imagine that in every prince’s palace, even in countries remote from Babylonia, there were scribes who could read and write the language and would translate the letters to their masters. The situation mirrored in these letters is a complex one.

The kings of Babylonia and Assyria, the kings of the Hurrian kingdom of Mitanni and of the kingdom of Alashiya, which may be Cyprus, wrote to the Pharaohs as equals. They were bound to them by treaties of alliance cemented by marriage and some of the letters discuss the amount of dowry which they propose to give to a daughter who is to be sent to Egypt to swell the Egyptian king’s numerous harem. Rich presents were exchanged and the vassal was to send a gift of gold equal value.

This was, in fact, trade: an exchange of goods, value for value, on an official basis and merchants were traveling as official agents of the kings and with their protection. Keftiu is not among those who sent these royal gifts: the Minoan envoys who once brought precious cargo from Crete to the court at Thebes came no longer. Knossos had been overwhelmed and was now in Mycenaean hands, but trade between Egypt and the Aegean continued and Mycenaean pottery is found in some quantity at Tell el Amarna. It has recently been suggested that the memory of the Minoan civilization of Crete, after the disaster which overwhelmed Crete and the islands, was preserved in Egypt and was responsible for the legend of Atlantis, the fabulous island in the west where life was lived in fine palaces with elaborate drainage systems and which was overwhelmed by the sea.

This story, according to Plato, was brought back from Egypt by his ancestor Solon. However this may be, it is true that in many details the description of Atlantis fits well with that which archaeology tells us of Minoan Crete and it is certainly tempting to see in one, a dim memory of the other. Letters from the regents of vassal kingdoms, which form the bulk of the correspondence, protest their loyalty to the Pharaoh and frequently complain of the hostile activities of their neighbours and the treachery of fellow vassals. They paint a picture of turmoil and intrigue. It is clear that Egypt’s control over her possessions in Syria and Palestine was far from complete and that the Pharaohs Amenophis III and Amenophis IV (known by his own wish by the name of Akhenaton) were occupied with problems of their own and failed to set forth on those constant demonstrations of strength and tours of inspection that were necessary of Syria and Palestine, if a ruler was to maintain a firm hold on his possessions.

Moreover, the Hittites were again casting envious eyes on North Syria. Some of the Amarna letters, from the vassals of Egypt in this region, show clearly how they were being forced or cajoled by Hittite agents into deserting their alliance with Egypt. Historical narrative texts from Hattusas (modern Boghazkoi), the Hittite capital, carry on the story of the Hittite capture of the kingdoms of North Syria and of the eclipse of Mitanni, from the Hittite point of view.

The Kingdom of Ugarit

One of the vassals of Egypt, whose king at this time was forced to change his allegiance and become a tributary of the Hittite king, was the ruler of the wealthy kingdom of Ugarit, on the Syrian coast north of the modern town of Lattakia. Excavations on the site of this city, the modern Ras Shamra, have revealed the size and importance of the town and its palace and here, too, valuable hoards of tablets have been found. Some of them are letters, couched in the same language of international diplomacy as the Amarna letters; they include the actual terms under which King Niqmaddu of Ugarit was to surrender to the Hittite king and the amount of tribute he was to pay. Other tablets refer to domestic matters and it is these, in particular the large number which are written in a simplified, alphabetic script of only thirty cuneiform characters, which give us insight into the daily life and beliefs of the people of this region in the fourteenth and thirteenth centuries B.C.

At Ugarit, which must be reckoned a Canaanite city, we find myths of the high god El, of the bloodthirsty virgin goddess Anath, of Baal the storm god, who was to be the adversary of Yahweh, the national god of Israel, and of Yam the god of the sea, with whom Baal did battle. Many of the rites of sacrifice, the festivals and even the poetic phraseology find close parallels in the Old Testament. This reminds us that the Hebrews came as nomadic wanderers into a civilization already old and absorbed and adopted from the Canaanites much that they found in the Promised Land.

The mysterious Khapiru

Yahweh himself, as might be expected, has no part in the pantheon of Ugarit, but Ugaritic texts more than once mention a people called the Khapiru, a name which many historians equate with the Hebrews. The Khapiru are found over a wide area of the Near East. There is considerable doubt whether the word denotes some sort of ethnic group, a nation or a tribe, or whether it denotes a social class — a turbulent semi-nomadic element in the population of the kingdoms of Syria and Mesopotamia, who drove their flocks about the countryside and frequently succumbed to the temptation to plunder the fields and herds of their wealthier, settled neighbours.

In the Amarna letters they are greatly feared marauders, a constant threat to the safety of the kingdoms of Syria and Palestine. They had evidently formed a considerable part of the population of “Retenu” (as the Pharaohs called Syria and Palestine together) in the time of Amenophis II, since he lists 3,600 of them among his prisoners. Later, about 1310 B.C., they were encountered by the army of Seti I during his Campaign in the Galilee area of Palestine.

The Khapiru are first mentioned as an element of the population of Mesopotamia, much earlier. So too are other Semitic groups. One of these groups, which received scant mention in the early texts but later grew into a formidable nation, were the Aramaeans. Hebrew tradition later affirmed that Abraham, their ancestor, had Aramaean kindred; the story of his wanderings from Ur to Harran fits well into a context of the years after 2000 B.C., when the lower Euphrates valley and the northern steppe-country (called today the Jezireh) between the Tigris and Euphrates were alike, the scene of bedouin movements and migrations. We will now see how they settled in Egypt and then at last went to Palestine the “Promised Land.”