The happy judgment of the historian Polybius on the strength of the Roman constitution, because of its mixture of popular, oligarchic and monarchical elements, might certainly appear as an optimistic theorization after the revolt of Spartacus. The Roman state had been shaken by a bitter and violent social disturbance that had only been resolved by two individuals whose power, though technically constitutional, was far too great for the Senate to feel comfortable. Crassus, the multimillionaire and Pompey, the popular general — had succeeded where the regularly appointed consuls had failed and the “extraordinary commands” with which they had been vested were a de iure recognition of the fact that the Roman state was now on the brink of being run by powerful individuals. The existence of such extraordinary commands, continuing until Octavian resolved the power struggle by his Victory at Actium and set about establishing the Roman Empire, with one individual in permanent possession of autocratic powers, indicates that the needs of the Roman state could no longer be met by using the established constitutional procedure. In the earlier days of the Republic, generals had been given special authority in the face of a serious military threat, but the Senate had carefully limited their authority and had been strong enough to keep control. If we look back at the period of Rome’s expansion into the Mediterranean, we shall see that the Senate had in fact, grown in strength, but that its increasing influence in government, also brought with it the potential for individuals to influence affairs.

The Roman Senate

During the Roman republic’s period of wars and expansions, from the time of the Punic wars onwards, the Senate, composed as it was of men whose experience and status gave them the ability to judge and make vital decisions in times of acute danger and stress, assumed greater direct responsibility in policy decisions. Since the early days of the Roman republic, the Senate had changed from being a council of men appointed by the consuls (as the successors of the kings) to being a governing body filled by ex-magistrates. The consuls would take their place in the Senate when their term of office was finished: hence a close attachment between these two “elements” of the Roman constitution. Thus the running of the state was concentrated in the hands of an oligarchy — the assembly of the Roman people still voted for magistrates, but had little real choice or influence in matters of government.

Within the Senate, cliques and power groups tended to form and aimed at dominating the conduct of government. The great hero against the Carthaginians, Scipio Africanus, was eventually forced to retire from public life because of the success of a coalition of senators hostile to him and his circle of relations and friends. This coalition indicates the tendency of the Senate to be dominated by groups of the most powerful of the Roman families, a kind of inner-circle of old and influential families, the nobiles, (those families who could claim a consul as an ancestor). The stage was thus set for the emergence of strong individuals, particularly if they had the glamour and popular support which attended a successful general, as Scipio had.

New Army of the Roman Republic

As long as the army of the Roman republic was composed of men from Italy who enlisted for a particular campaign and were subsequently disbanded, the loyalty of troops to an individual general was limited. However, Roman republic found herself almost constantly involved in peace-keeping or in actual wars and this meant a constant demand for troops. The solution from the military point of view was the creation of a professional standing army and this was achieved at the end of the second century B.C., under the leadership of a solid Italian soldier, who had risen from the ranks to command the armies of Roman republic, Marius. Once a campaign was over, the troops did not disband and return to their villages and towns as before: they now stayed together as a professional fighting unit, in need of employment as soldiers and looking to their leader for guidance.

The curse of the Hellenistic age had caught up with Rome. Generals and their armies would henceforth face each other on Roman soil, to determine who might control the state. The problem — of what to do with a standing army was not even approached until Rome truly became an Empire under Augustus, when he arranged for most of the troops to be stationed on or near frontiers — was never solved. The authority of individual emperors, backed up by a willing Senate, kept the problem at bay for the most part in the early Empire. In the third century A.D. the Empire was to go through a severe crisis, one of whose main causes was the rapid turn-over of emperors, made and unmade by the army.

Political Reform

The Challenge of indixidual politicians to the collective authority of the Senate did not at first come from within its own ranks, nor yet from generals. The Tribunate, originally created popular pressure to give voice to the demands of the people’s assembly and to provide a counter-balance to aristocratic poyer, provided the Vehicle of protest — and almost of revolution, for two brothers, the Gracchi. Tiberius Gracchus attacked serious flaws in the Roman government from his position as tribune of the people in 133 B.C., calling for agricultural reforms to the peasantry.

In attempting to achieve ratification of his proposals, he managed to get his fellow Tribunes deposed and was labelled by the senatorial opposition as a demagogue seeking autocratic powers. The fear of autocracy (one thinks of the traditional hatred for kingship) among Romans provoked a violent reaction: Tiberius was killed. So was his younger brother Gaius Gracchus, who had taken up his brother’s cause and was campaigning on behalf of the people and on behalf of the equestrian class of citizens (the businessmen of Rome, below the senators in rank), whose interests were not represented politically. Such violence in politics struck a new warning note; so did the great wave of popular support which had temporarily carried the Gracchi forward into a position of dominance. The state could be swayed by individuals and the whole direction of Roman government, despite its apparently solid framework, could be altered.

The passionate respect which the Romans of the time had for their constitution, reflecting no doubt their genuine sense of stability, was to limit any attempts at real change. Marius, the Italian soldier-become-general, with the aid of help from an ancient and respectable senatorial family, the Metelli; and the support of the people and his troops, eventually dominated the Roman state. His overthrow was accomplished by a man who was a conservative, who was backed by the Senate and who set himself up as dictator to patch up the haws in the Roman constitution. This senatorial candidate, Sulla, produced a solid if backward-looking program of reform before stepping down to let the constitution work without the guiding hand of an autocrat. Unfortunately, for all the semblance of a senatorial revival and an apparent return to the days when Rome was run along constitutional lines, politics was still at the mercy of individuals and no issue could really be decided without an army.

This was clear when, some twenty years after the reforms of Sulla, the victorious Pompey returned from his campaigning in the East. He had pacified the rebellious territories there and laid the foundations for their administration as Roman provinces (permanent annexation was replacing diplomacy almost everywhere within the Roman orbit), but his extraordinary command had been voted to him by the people. Since he was not a senatorial candidate, the Senate refused to ratify his arrangements. He could exert no pressure on them because he had disbanded his army, perhaps foolishly under the circumstances. It took pressure from another individual with an army, Julius Caesar, to get Pompey’s work ratified.

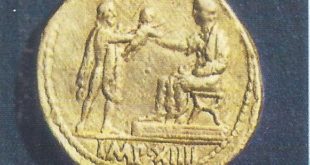

Julius Caesar

Thus the late Republic drew to its end with military power paramount. The years before the battle of Actium, which was finally to resolve the crises of the Republic, were dominated by soldier-politicians like Pompey and Julius Caesar. Later, by Antony and Octavian. Their support came not just from their armies (officially legions representing the Senate and people of Rome, but in practice private armies), but intermittently

from the people of Rome, whose influence was temporarily-even if not eHectively-increased by the political auctioneering that took place. The Senate itself was divided according to the inclinations and interests of its individual members. As a group it gravitated towards support of Pompey against his former ally Caesar, when Caesar in his campaigns and administration of the new provinces in Gaul showed himself to be too successful and clever for the Senate’s liking. Caesar proved his superiority by crushing Pompey and his legions in a civil war in Italy itself. He controlled the Roman state for four years, until he was murdered in 44 13.0. for, so his opponents claimed, setting himself up as a “king” over the Republic. His nephew Octavian inherited his political support, and as we shall now see, finally put an end to the political competitions that were exhausting the resources and vitality of the Roman state.