Cruelty showed itself only two years after Pericles was dead. In 428, after the usual spring invasion by the Spartans and before the Olympic games, which were being held as usual, Lesbos had revolted. The Spartans had promised to help the Lesbians and in the following year their fleet at last arrived — a week too late. Mytilene, the capital of the island had already surrendered to the Athenians.

The Athenian Assembly now had the people of Mytilene at their mercy. They voted that every man should be put to death, the women and children enslaved. A trireme was sent off to carry out this order. Next day the Assembly came to their senses and sent out a second trireme to countermand the instructions for massacre. It was only just in time.

The person responsible for persuading the Assembly to take their first, disgraceful decision was Cleon, a tanner. The Athenian democracy had reached the point where what is now called “the common man” could obtain supreme power. The politicians, instead of being land-owners, were people who made things, they were people who bought and sold things.

The 40,000 citizens of Athens, among whom small craftsmen and traders were the majority, had so far been content to enjoy their privileges (e.g. payment for jury service, payment for sitting on the Council of 500) while allowing an aristocrat, Pericles, to lead them. Now they wanted positions of power as well as privileges; and they got them. They had to struggle among themselves first. Dozens, hundreds perhaps, would have liked to exchange the petty power over a few slaves and apprentices, which they enjoyed in their workshops, for the position of one of the generals of the Athenian people. It was useless for them to try and reach that position by being dignified, like Pericles. The Assembly expected a rich land-owner to be dignified; but if a tanner had tried that approach, they would have thought he was putting on airs. The only way for a tanner to win the Assembly’s confidence was for him to shout much louder than anyone else and to shout the sort of speeches which the Assembly would like to hear — to be led by them, that is to say, instead of leading them (a reversal of the policy of Pericles). Thus, like a cheap newspaper struggling for high circulation figures, Cleon pushed his way to the front.

Nevertheless, by a combination of pushfulness and good luck, Cleon managed to provide Athens with a sight which, at that time, was more heartening than her marble temples, more moving than the work of her tragedians and good for a louder, more contemptuous laugh than anything Aristophanes the writer of comedies could put on the stage. Cleon marched three hundred Spartan prisoners through the town (425).

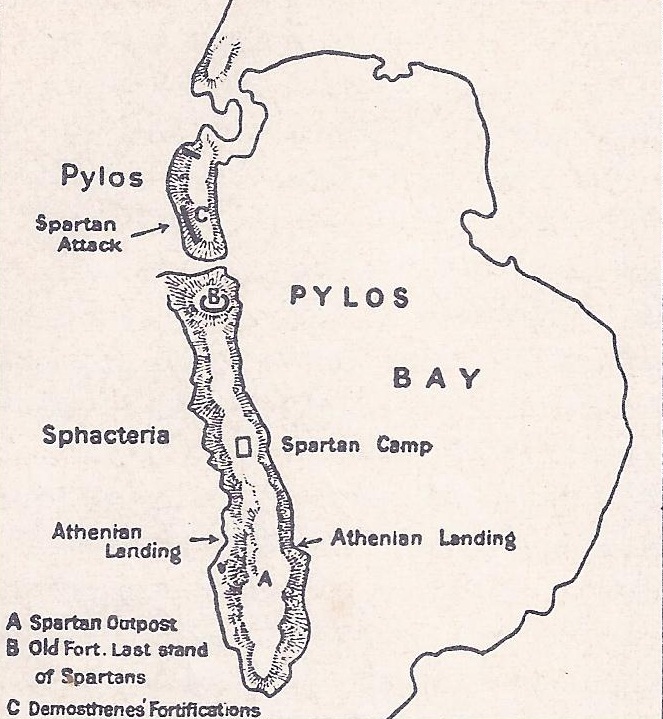

These men had been blockaded by the Athenian fleet on the island of Sphacteria, in the western Peloponnese. They were now haggard and in rags but at the beginning of the operation they had been a noble company of Spartan soldiers. The Spartans valued them highly. They could never afford losses which might make them too weak in numbers to resist an attack from the watchful, bitter Helots. They sent ambassadors to ask for peace terms, but Cleon and the Assembly did not want peace. Athens was prosperous. Craftsmen and traders were doing well. They wanted to keep the Empire which they already had in the Aegean and then to supplant the power of Corinth in the west. Peace with Sparta meant peace with Corinth. They were against it. So Cleon would not let his Spartan captives go and in order to pay for the continuation of the war, he persuaded the Assembly to double or in some cases treble the tribute paid by the “allies” of Athens.