The Great Wall of China did not always keep the invader out, but it did help to establish the geographical identity of the Chinese empire. The exact delineation of the boundaries of the empire gave its administration a positive geographical basis. Rome, similarly, can be traced by the vicissitudes of her rise – from small city-state to mistress of the Mediterranean world and Europe. The ultimate extension of Rome’s power gave her a vast empire and as with the empire of Shih-huangti, her territory was given a positive limit by permanent frontiers. The Great Wall of China has a smaller but still monumentally impressive parallel in Hadrian’s Wall, built in the first years of the second century A.D. across the northern part of England, to keep out unconquered tribes from the north.

The whole of the Roman Empire was ringed with systems of fortifications when natural barriers were not present, as the great forts of Germany and the limes (frontier system) of North Africa indicate. Here described is a remarkable episode. It is the story of an enemy of Rome who invaded Italy and conquered what one would have supposed was an insuperable natural barrier, the Alps.

Hannibal

The enemy was the Carthaginian leader Hannibal. His epic journey across from North Africa up through Spain, across southern France, over the Alps and into Italy is in the tradition of Alexander’s vast journeys across deserts and mountains to conquer half the world. Hannibal himself was a true product of the Hellenistic age that Alexander’s conquests had ushered in. It was an age of the professional war-leader. The outcome of military struggles largely determined the political development of the Mediterranean world at this time and the leader of a powerful army could carve out a kingdom for himself.

Military power had assumed greater importance since Salamis; the size of the confrontation, the empire of Persia against the Greeks, was significant. In the East, Hellenistic princes made and unmade states. In the West, meanwhile, relatively modest campaigns in Italy were gradually bringing to power a small city-state. By 270 B.C., Rome had consolidated her position as the dominant power in central Italy.

Before we study the course of events that led to conflict with the North African empire of the Carthaginians, it is worth looking at how the city of Rome, now on the brink of a Mediterranean expansion that would lead to world domination, had grown.

Origins of Rome

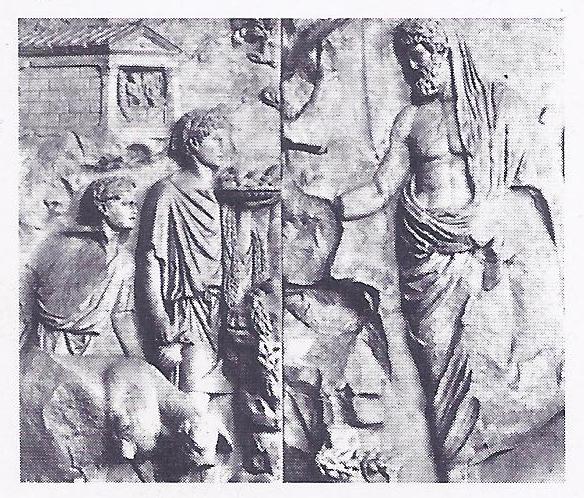

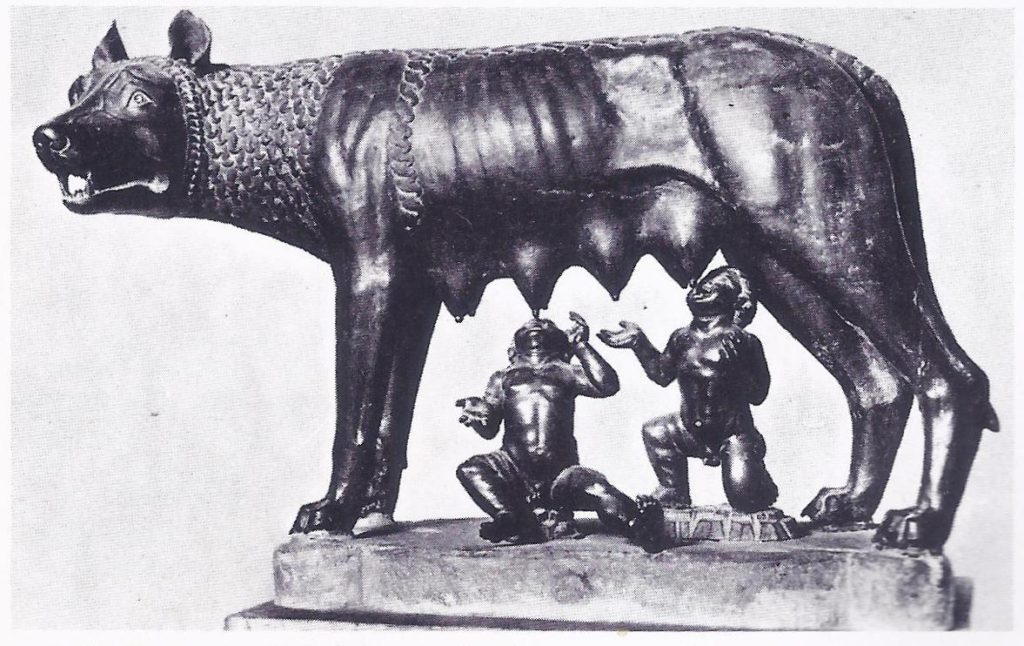

The Greeks, possessed very little information about their origins, though the Homeric epics had preserved for them some indications of a historic past. The Romans knew even less about their beginnings as a state and for them legend provided the traditional account of Rome’s early history. According to legend, Rome was founded in 735 B.C. by Romulus, son of Mars, on the hill known as the Palatine above the Tiber River. Rome’s original constitution was monarchic; seven kings ruled over Rome until the last, Tarquinius Superbus, was driven out and a republic set up. The last three kings were Etruscan.

According to archaeology and modern historical analysis, Rome was founded sometime in the eighth century B.C.; the oldest settlement, which was on the Palatine, merged with other settlements on the group of seven hills above the Tiber and the hill called the Capitol, was subsequently fortified. Rome’s local power grew and she gained the leadership of neighbouring Latin towns, forming a league.

Rome Looses to The Etruscans

The rise of the Etruscans to power in central and northern Italy precipitated a clash with Rome. Rome lost the struggle and an Etruscan ruling house took over. Under this leadership Rome grew and prospered, learning the skills of civilization from the Etruscans as they had learned them from the Greeks, but at the beginning of the sixth century, the Etruscan domination was ended by a rebellion engineered by the more powerful families in Rome and a republic was set up.

Society of Rome

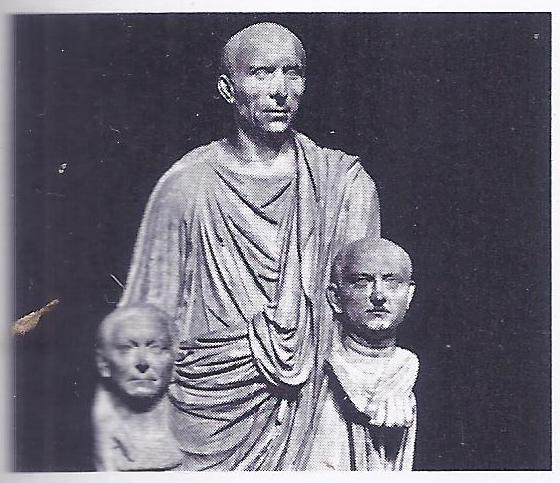

Rome’s population was made up of various families or clans (gentes). Certain families were more important than others and their heads functioned as a council of elders, called the Senate. In the days of the monarchy this council was he source of advice for the king, was also chosen from the ranks of the senators, or patres (fathers), as they were then called. The more important and richer families, the patricians, were distinguished from the lesser families, the plebeians. After the explosion of the Etruscan Tarquin, two magistrates were henceforth elected instead of a king, they were later to be known as consuls.

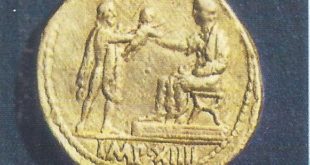

The word for king, rex, became a hated symbol of excessive power and it was never again used officially. When centuries later, the Roman republic was transformed into the Empire under Octavius, the emperors, even though they were sole rulers at first, never used the term, but called themselves imperator (general, or one who exercises supreme power, imperium).

Patricians and Plebeians

The decision-making body of early Rome was theoretically the comitia. or popular assembly, but in practice the Senate exercised power over it. In contrast, at Athens, the popular assembly eventually curbed the power of the great nobles; Rome was thus never a democracy in the way that Athens was, but basically an oligarchy, increasingly dominated by powerful individuals. Unlike many Greek cities, Rome did achieve internal stability and developed her constitution (and perhaps almost as important, a respect for it) without civil wars and the forcible imposition of rule by one group or another. The patrician and plebeians engaged in a long-drawn-out struggle for power, which was not simply rich against poor for the ranks of the plebeians eventually contained influential families. The plebeians managed to obtain recognition of their own officials, the tribunes, who were then incorporated into the constitution of the Roman state. The calm conduct of what was a very real struggle is evident in the so-called “succession of the plebs,” when the plebs withdrew their labour until their demands were met, thus showing by passive means their relevance to the Roman state.

Rome’s Citizenship Policy

In contrast to the Greek city-states, Rome’s expansion did not stop at temporary domination over neighbouring states. The Greeks, always respecting the idea of the autonomy of the city-state, did not conceive of a larger unity except in the form of a hegemony, or league. The Romans conquered peoples and cities in Italy, but their hegemony brought with it the chance of assimilation. Rome’s “allies” received certain of the rights of Roman citizenship and eventually all of Italy gained full Roman citizenship. The people of Rome, as in other city-states, had political expression through citizenship, but what distinguished Rome from city-states like Athens for example, was the emergence of the idea that citizenship could be extended wholesale to other peoples. This larger concept of citizenship paved the way for the absorption of foreigners and the resulting political unity that was to be the mainstay of the Empire of Rome. Alexander’s conquests had let loose the idea of a community of Greek culture that embraced the whole inhabited world, the oikoumene; the oikaumene was to be given a political framework within the conquests of Rome which provided for the continuity of Greek, or rather Greco-Roman, civilization around the Mediterranean.

Pyrrhus of Epirus

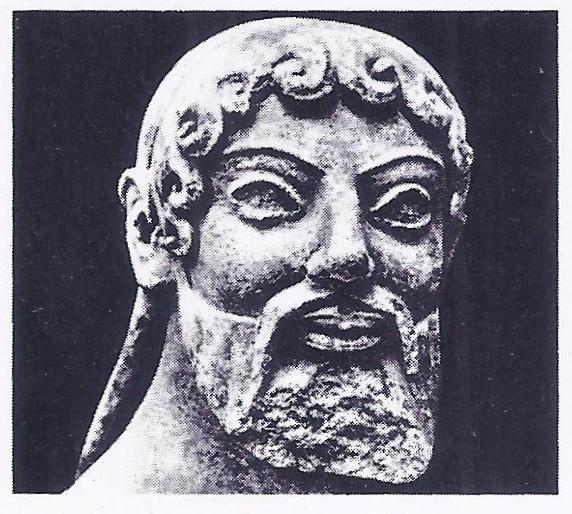

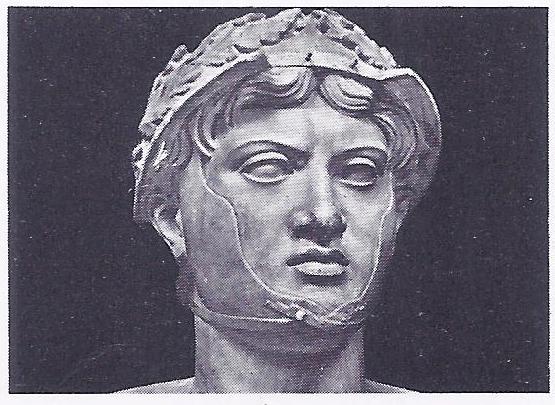

We now take up the story of Rome when she was as yet only a force inside Italy. In 270 B.C. Rome became involved in the quarrels of the Greek cities in the south of Italy. Her strong position in Italy gave her the potential role of arbiter, if not protector. In a dispute between Thurii and Tarentum, Thurii appealed to Rome for help and it was given. Rome had entered the sphere of Greek polities. The Tarentines, who saw Rome as a threat to their supremacy in southern Italy, enlisted the help of Pyrrhus, King of Epirus.

Pyrrhus was a condottiere in the Hellenistic style, looking for a profitable cause to fight for, since his attempts to grab territory in Greece while the successors of Alexander were squabbling for power had been unsuccessful. Rome’s first confrontation with the professional skill of Hellenistic mercenaries did not go well at first and after a defeat at Heraclea, the Romans were forced back deep into Latium. The possible threat to Rome itself galvanized the Romans into uncompromising action: Pyrrhus was seen as a real danger to Rome herself. He might play the war game for profit as did most of the Hellenistic war leaders, but Rome was in deadly earnest. Their stubborn efforts inflicted so many casualties on Pyrrhus that, although technically Victor, he decided to withdraw from Italy (hence the proverbial Pyrrhic victory). He sailed off to Sicily to try his luck fighting for the Greek cities there against the Carthaginians. After a second try against the Romans in Italy, again without any real success, he returned to Greece where he was killed in a brawl at Argos.

Conflict with Carthage

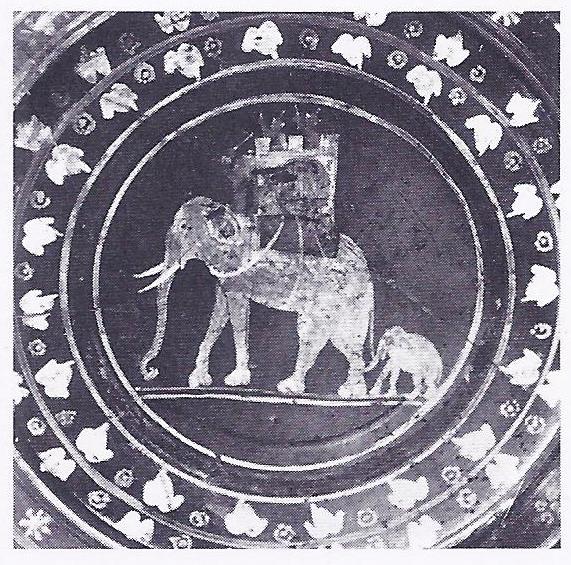

Behind such campaigning, the realities of politics brought Rome and Carthage to a head-on collision. Carthaginian power had only just been kept at bay by the Greeks in Sicily for centuries. Rome’s interests and her involvement with the Greek cities of Magna Graecia, meant that two spheres of influence were beginning to overlap. Conflict came when Rome embarked on armed intervention in Sicily. The struggle with Carthage that followed was to last intermittently for more than half a century (264 – 202 B.C.), with the three Punic Wars – “Punic” from the Latin poeni, poenicus meaning Phoenician. For Carthage was the greatest off-spring of Phoenician colonization in the western Mediterranean. Her great strength was her navy and Rome was forced to become a sea-power almost overnight in order to have even a chance against the might of Carthage. Carthage was, unlike most Phoenician colonies, also a great land power, whose vast territories in North Africa, stretching as far west as the Straits of Gibraltar, added to her possessions in Sicily and Sardinia, made her one of the foremost powers in the Mediterranean.

The First and Second Punic Wars

The first war with Carthage ended with the ceding of Sicily to Rome, the first of Rome’s overseas acquisitions and the beginning of her Empire. The Second Punic War brought to lasting fame, the Carthaginian whose remarkable journey across the Alps is also a historic milestone. Hannibal was a great war leader, but he is distinguished from other Hellenistic captains of war by his sense of mission. It may not be acceptable to talk of destiny today, but to Hannibal and to the Romans it must have been a more valid concept. The destinies of Rome and Carthage were seen as intertwined in the Homeric past by the poet Virgil, who composed his epic poem The Aeneid in the reign of the Emperor Augustus. In this backward projection of history, the hero of the poem, Aeneas, a Trojan prince, leaves the ruins of defeated Troy and journeys to Italy to establish a new Troy – Rome – on the seven hills. On the way he stops off on the coast of North Africa, where he loves and leaves Dido, Queen of Carthage, who is building her great new capital. The deserted Queen swears perpetual vengeance against Aeneas’ descendants and commits suicide. Hannibal is said to have sworn revenge on Rome on the altar of Melgart and his mission of revenge against the armies of Rome.