Hannibal alone, would have dared embark on such a venture. Two powers confronted each other to dispute mastery of the Mediterranean — Rome and Carthage. The Carthaginians were interested in colonial expansion as an extension of their trading interests, but were prepared to protect those interests if necessary. Rome’s view was essentially different.

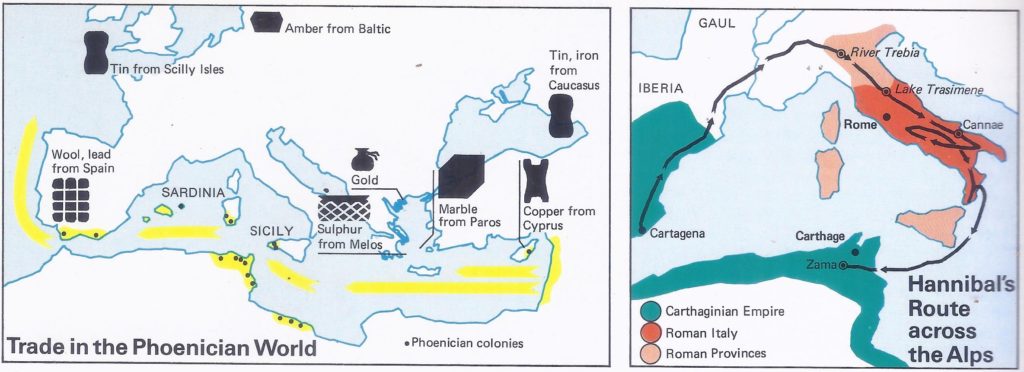

In fact, some Romans believed that the fates of the two nations were inextricably linked and that they were doomed to a duel to the death. Carthage’s sphere of influence extended over a great deal of the western Mediterranean, so Rome had to become a naval power virtually overnight. Carthage too was arming for the confrontation and under the leadership of the general Hamilcar moved the theatre of war to Spain. It remained for his son Hannibal — one of the greatest military geniuses of all time — to challenge the Romans on their homeground by crossing both the Pyrenees and the Alps. In the ancient world such a feat seemed impossible.

In the spring of 218 B.C., an army of 100,000 men gathered in a town in eastern Spain, now Cartagena, under the command of a young general, Hannibal Barca. These soldiers had been recruited from all the warlike tribes of Spain and North Africa. The officers were Carthaginians, descended from the ancient Phoenician people who had left the Lebanon six or eight centuries earlier and had colonized first the coasts, then the interiors of present-day Tunisia and Andalusia. In the next two years these men were to accomplish one of the most astonishing feats of history. They were to travel more than 1,200 miles through hostile or savage countries, crossing one of the biggest rivers in Europe and two of the highest mountain chains. At the end of this formidable journey they were virtually to annihilate the finest armies of the time and to threaten the very survival of Rome’s power in the heart of her own territory.

Hannibal’s aim was to avenge the defeat that Rome had inflicted on Carthage twenty-three years earlier, at the end of the First Punic War, a struggle that had lasted for nearly a quarter of a century. (The Punic Wars were so called after the Roman name for Carthaginians: Poeni, i.e., Phoenicians.) His fantastic venture so astounded both his contemporaries and posterity that its romantic aspect has overshadowed the rational, one might almost say scientific, manner in which the undertaking was planned and executed. The facts, however, emerge from the account given by the Greek historian Polybius, one of the soundest intellects of antiquity despite his Roman bias. Thanks to him, we realize that Hannibal’s campaign was not the whim of a rash young leader; it was prepared and led by one of the greatest political figures of all time. In spite of ultimate failure, it influenced decisively the evolution of Mediterranean civilization.

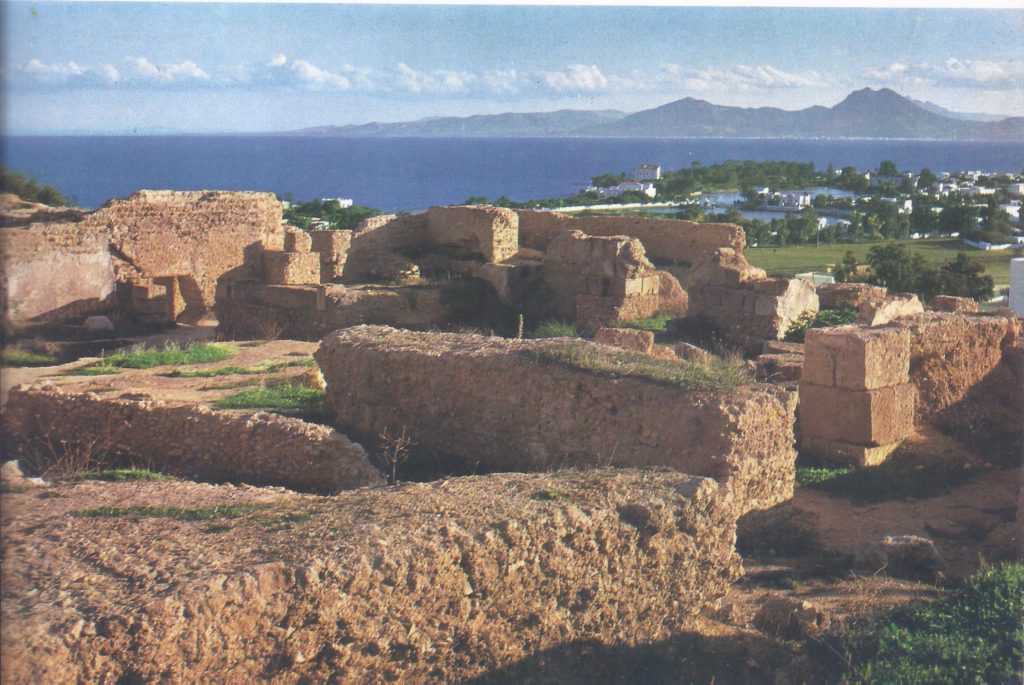

By the end of the fourth century B.C., Carthage had accumulated great wealth from its vast trading empire. Its kings had brought terror to the Greeks in Sicily, conquered Sardinia and sent exploratory expeditions along the river banks of tropical Africa and the boundaries of Europe. Carthaginian dominance over the western Mediterranean was well established. Then the great landowners rose to destroy the monarchy and for a time Carthage had sought to live at peace. Concentrating on trade, she had allowed the militant Roman republic to establish power over the whole of Italy without making any move and had even refused to help her old allies the Etruscans, in spite of centuries-old treaties of mutual aid. The peasant soldiers of Latium had no apparent reason to interfere with Carthaginian merchants and Rome’s still-primitive economy could not rival the highly developed scientific agricultural system of the vast African estates.

Some of the Roman senators, however, had formed fruitful associations with the merchants of Campania, who had pointed out to them the enormous profits that would accrue from the conquest of Sicily, the granary of the western Mediterranean, a great cultural centre — and an island partially under Carthage’s control. In 263 B.C. a Roman force had occupied Messina, thereby securing control of the straits between Sicily and Italy. Carthage could not tolerate this encroachment in an area that she considered as belonging to her “governorship” of Sicily and the First Punic War broke out.

During the first years of the conflict, the military superiority of the Romans on land was evident and the Roman fleets held their own against the celebrated Carthaginian navy. The Carthaginians were able to retain only a few bases in Sicily and that much was salvaged only because of their superiority in siege warfare. In 256 B.C. the Romans, led by Regulus, were halted on one of their forays into Africa. The conflict had reached a stalemate. This prolonged warfare, however, was disastrous for a country with a mercantile economy, such as Carthage. Exhausted and discouraged, in 241 B.C. the Carthaginian government finally renounced all claims over Sicily.

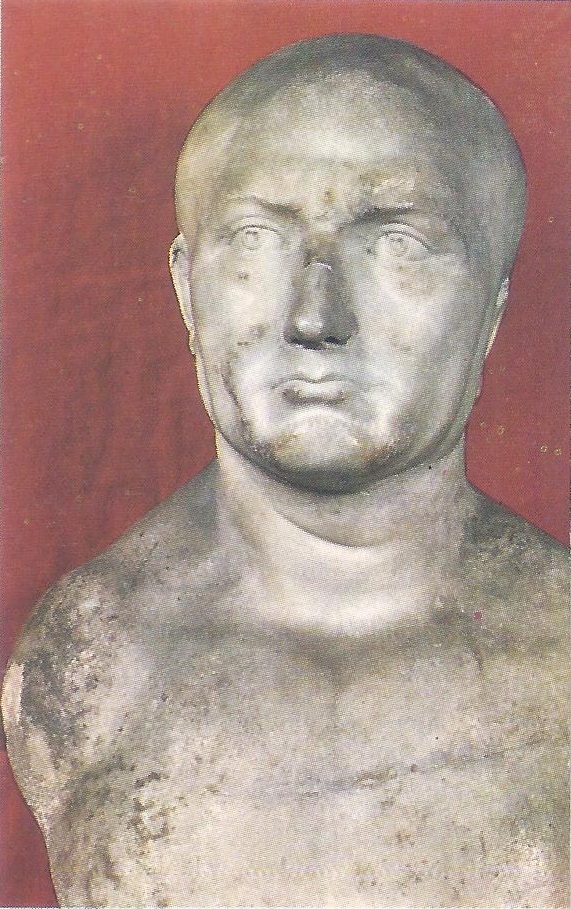

Confrontation between Rome and Hannibal of Carthage

Following the end of the war, a grave social crisis was precipitated in Carthage by the mutiny of the mercenaries who had formed almost the entire part of the Punic army. The government fell and was replaced by a popular party, which handed power to Hamilcar Barca, Hannibal’s father. This young general, already famous as head of commando units against the Romans, succeeded in controlling the mercenaries. Hamilcar recognized the basic weaknesses of the Punic government — weaknesses that had contributed to the loss of the war, as well as, to the revolt of the mercenaries. The problem was that government was in the hands of a self-centered plutocracy, with the ruling families vying with one another for power. While Hamilcar had little interest in internal politics, he modified the constitution to the extent necessary for him to carry out his plan of revenge against Rome.

Hamilcar did not in fact accept any possibility of compromise with the belligerent Italian republic. The Roman Senate had not attempted to subjugate Carthage even during the mutiny of the mercenaries, perhaps for fear of widespread revolution, but toward the end of Carthage’s internal crisis, Rome had annexed Sardinia, cynically and without regard for justice.

Hamilcar had three main aims: to have a free hand politically, without being obliged to account all the time to the rulers of Carthage; to be solely responsible for the country’s economy and free to use its resources to influence both internal and foreign opinion; and to recruit an army that was efficient, well-trained and completely loyal to him personally. He achieved all three aims in less than ten years, thanks to his conquest of southern Spain, which he organized into a virtually independent kingdom on the model of those that Alexander’s successors had created in Asia.

The mountain chains of Andalusia concealed the richest mines in the Mediterranean world. These provided enough revenue to pay Rome the war reparations fixed by treaty, to afford resources for Hamilcar’s electoral campaigns in Carthage and to hire Greek technicians and propagandists necessary for his great plan. The war-like Celtiberian tribes provided courageous soldiers whose fervent loyalty to their leaders offset the disadvantages of their rapacious behavior. All this took place on the fringe of the civilized world, beyond the regions regularly inspected by the Roman intelligence service.

Hamilcar was killed in a campaign in 229 B.C. The system of succession that he had devised required that one of his close relatives should succeed him. His eldest son Hannibal was still too young and power passed into the hands of his son-in-law, Hasdrubal. He continued to organize the Spanish kingdom, but he seems to have sought to delay any further conflict with Rome.

The Greeks of Massilia (now Marseille) and of Emporiae in Catalonia, old enemies of the Phoenicians, had finally persuaded the Romans of the danger that the Barca empire represented. Hasdrubal signed a treaty that set the boundary of his domain at the river Ebro, or possibly the Jucar, but Hasdrubal was assassinated and in 220 B.C., Hannibal succeeded to power.

Hannibal at once adopted a more uncompromising, aggressive policy. To make it quite clear that he ruled Spain and that his enemies could expect help from Rome, he attacked and destroyed the Spanish town of Saguntum, which had a treaty of alliance with the Roman republic. The Senate, which had done nothing to save the people of Saguntum, demanded the punishment of the Carthaginian “butcher.” The Carthaginian government replied that the Barca state in Spain was autonomous and that Rome had recognized this when negotiating with Hasdrubal. The Roman ambassador could only point out the inevitability of war.

The Second Punic War was welcomed by Hannibal; his moral responsibility for it was largely justified by the brutality and cynicism of Roman policy toward Carthage. The only question was whether the young Carthaginian leader had a reasonable chance of winning. Hannibal was convinced he had that chance. Educated by Greeks, he had broadened his outlook to embrace the whole Mediterranean world and even the uncivilized countries beyond. No other statesmen except perhaps Alexander and Pyrrhus of Epirus had attained so international an outlook; and the quality of the information at the disposal of the Carthaginians made Hannibal well qualified to assess the geographical and political situation.

Hannibal had carefully considered the structure of the political organization that we call, rather loosely, the Italian confederation. It had been created by linking the military power of Rome with the economic and commercial strength of Campania. Both parties had derived considerable benefits; for the legions constituted the strongest armed force in the Mediterranean and the merchants and manufacturers of Campania dominated the whole market from Gibraltar to the Adriatic. However, its very success was a source of rivalry between the partners. For one thing, all important policy was decided in Rome and statesmen of Capua did not take kindly to having their ambitions restricted to a municipal scale. In addition, the constitution of Capua favoured the development of what we would now call left-wing ideas whose supporters — in particular a certain Pacuvius Calavius — foresaw the breakup of the union. It is more than likely that these potential secessionists had made a deal with the Carthaginians before the outbreak of the Second Punic War.

If she were to be deprived of southern Italy, Rome would at once lose all her naval power — unequaled in the Mediterranean — and Carthage could have regained Sicily and Sardinia without striking a blow. However, no one in any Italian town would dare oppose Rome so long as the legions controlled the country. Therefore, a force had to be found that was capable of neutralizing the Roman army. Hannibal thought he might find this force in Gaul. For a long period the Celts had provided mercenaries for the Carthaginians, but no one as yet had the idea of treating these barbarians as a political force and concluding diplomatic agreements with them.

One of the greatest errors of the Carthaginian government during the First Punic War had been its ignorance of the profitable use it might make of the Gauls in the Po Valley. In fact, the Gauls had remained at peace throughout the war and had subsequently been subjugated by the Romans. Hannibal was determined that the same mistake should not be made again. He sent envoys throughout the Celtic territory, who brought back extremely useful information.

Until this time, the Gauls had occupied the centre, the east and the north of France, Holland and western and southern Germany. The Rhine ran through the middle of their territory. For several decades, however, the Celts east of the Rhine had been forced by the Germans to fall back toward the west and the south, driving before them tribes who had previously been settled in the west. This large migration had taken place around 230 B.C.; it was then that the Gauls settled and founded their towns, Paris among them. The repercussions of this great upheaval were felt to the limits of the Celtic world. In 225 B.C., the Romans found themselves face to face with bands of Germans mixed with Cisalpine Gauls.

For Hannibal, this situation offered a double opportunity. For one, there was the possibility of recruiting seasoned auxiliaries from the numerous tribes who had been uprooted. Of even greater importance, the major difficulty facing a Carthaginian expedition from Spain to Italy was overcome. The Mediterranean Coasts of Languedoc and Provence, had until then, been occupied by Iberian and Ligurian tribes, who were partly Hellenized, as a result of three centuries of trading with the Greeks. The politicians of Massilia could easily have raised from among them numerous opponents to Hannibal’s passage. However, at about 230 B.C. the whole area between the Pyrenees and the Rhone had been subjugated by a Celtic tribe, the Arecomican Volsci. Hannibal had only to reach agreement with them to gain not only the right of peaceful passage, but also, long-term occupation of certain garrisons. By maintaining these, Hannibal could retain his lines of communication with Spain and could receive reinforcements, as was to be the case in 208 B.C. At the same time he could prevent Roman armies from invading Spain by land.

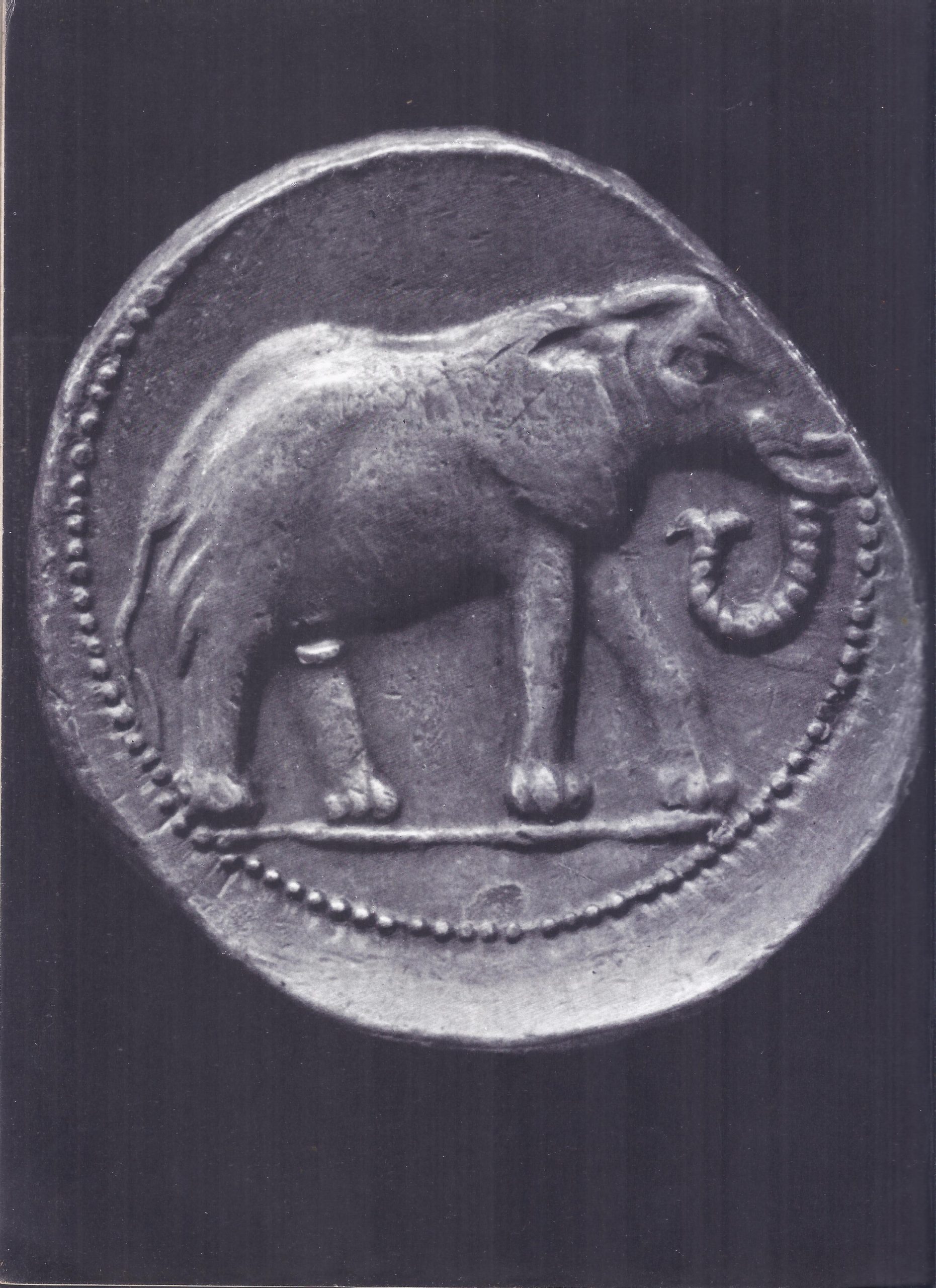

In the light of such considerations it becomes clear that Hannibal’s decision to invade Italy by land was not just a bold act of desperation. In fact, he had no other means of surprising an enemy whose defenses were otherwise impregnable. The only important problem that confronted the expedition was that of supply; and Napoleon himself remarked that such obstacles must never stand in the way of strategy. In this case, the invading army compensated for its weakness by the factor of surprise. Hannibal, only too well aware of the importance of propaganda, knew how to exploit the impression his extraordinary venture would make on public opinion. He could not foresee, of course, that this impression was to last for more than twenty centuries. Even today, most people remember Hannibal chiefly because he brought his elephants across the Alps.

We do not know with certainty the route Hannibal took across the Alps. It seems most likely that he crossed the valley of the Isere, through Maurienne and Mont Cenis. This route allows for one of the few authenticated traditions: that Hannibal passed through the Allobroges’ territory. However, proof remains impossible.

The destruction of Roman military power and the dissolution of the Italian confederation were accomplished as Hannibal had planned and with remarkable speed. The battle of Cannae on August 2, 216 B.C., following upon those at Tessin and Trasimeno, deprived Rome of a third of its forces and that third, comprised the youngest and most vigorous elements. Then the large towns of Campania and the Greek cities of Capua, Tarentum and Syracuse defected from Rome and the Punic fleet was able to come into action.

Suddenly, however, the fortunes of war changed, the reasons for this reversal are much more complex than the reasons for Hannibal’s success. Hannibal himself can be absolved from the accusation usually leveled against him, that he lacked decisiveness in failing to make a frontal attack on Rome after the battle of Cannae. In fact the capitals strategic position was so strong and its perimetre so well equipped with the latest Greek defensive weapons, that a siege would have been extremely hazardous for an army already reduced and encamped in a hostile country. A heavy responsibility, however, must surely rest on the Carthaginian admirals and the leaders of the various rebellions against Rome, who failed to coordinate their efforts and thus allowed the Romans extinguish each outbreak in turn.

Hannibal himself made two bad errors of judgment; he under-estimated the capacity for resistance of Rome itself, strongly ensconced as it was on plains surrounded by the mountains of Latium and the Sabine territory; and he over-estimated the stability of the Barca kingdom in Spain, which collapsed like a pack of cards in the face of the small army of the Roman general Scipio. On this last point there is no doubt that Hasdrubal had seen the problem more clearly and had recognized the necessity of strengthening the Spanish state before embarking on so hazardous an expedition. In any event, Hannibal was forced to return to Carthage and at Zama in 202 he was decisively beaten by Scipio. By the terms of the peace treaty of 201, Carthage lost its navy and its empire.

Hannibal’s Ambition Thwarted

Hannibal was a victim of his Greek education. The successes of Alexander had accustomed men of that time to imagine that history was made and unmade by a few outstanding men helped by a handful of adventurers and that economic, social and cultural factors or the popular mood could be discounted. The Barcas had hastily imposed a quite artificial political structure on the multitude of small and disparate social groups that inhabited the Spanish peninsula. The Roman state, on the other hand, had grown slowly by a natural process. Those who came to belong to Rome were not even completely aware of having been Romanized, but the process had altered their attitudes and created among them indissoluble bonds. Hannibal’s sudden challenge could not interrupt Roman development, but it both modified and furthered the confederation by shattering the framework within which it had operated and allowing Rome to expand throughout Italy and the Mediterranean.

Thus Hannibal must be considered one of the chief instigators of the great revolution that transformed Mediterranean civilization and gave birth to the modern world. It is interesting to note that this view of Hannibal is substantially the same as that held by the Roman historians themselves, who saw the Carthaginians as a divine instrument sent to try the Roman people, purging them through suffering and thus making them more worthy of their divine mission to govern the world.