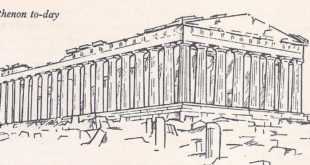

In the year 437 the Parthenon, which had been begun ten years before, was far enough advanced to contain a gigantic statue of Athena by the sculptor Pheidias. Enough of the Parthenon still survives to give an idea of how it must have looked when it was new and a visit to the British Museum will fill in the details. Here some of the sculptured figures which adorned the temple may be seen. They are known as the ‘Elgin Marbles’ because Lord Elgin brought them back from Greece in 1802-4 to save them from Turks, who then ruled the Greeks. …

Read More »Hellenes – Ancient Greek Mythology

Herodotus, The Father of History

In 445, if tradition can be trusted, the Athenians must have felt more self-confident than ever; for it was then that Herodotus came to Athens, read aloud his history of the Persian wars and was given a reward. That the Athenians should have listened with interest as well as gratification is not surprising. The historian had done full justice to their distinguished part in the Persian Wars and in addition his work (9 books in all) contained all sorts of interesting details about countries like Egypt and Scythia (south Russia) which were only remotely connected with the war. Herodotus had …

Read More »The Athenian Empire

Cimon was rich and pro-Spartan, but generous. He kept open house and invited the public to make use of his garden and grounds. It was said that he got riches that he might use them and used them that he might get honour by them. This was in fact the course which Athenian Empire herself now began to adopt; but Cimon was not destined to steer her along it. He had a rival, Pericles. In 461 the queer process of ostracism was once again brought into operation. (For the events leading up to this see) Every citizen scratched a name …

Read More »The Confederacy of Delos

Delos a Greek island in the Cyclades archipelago was an important religious centre in the Archaic and Classical periods. The island was also a major commercial and trading centre in the 2nd and 1st centuries CE. About the same time as the land victory at Plataea (479) the Greek fleet had beaten the Persians at Mycale on the coast of Asia Minor (478) and now that they were absolutely sure which was the winning side the Ionian Greeks of the coast and the islands gradually decided to change sides again, but they needed help. Persian garrisons had to be driven out. The Spartans might have …

Read More »Theseus Comes Home

The annual festival of the Great Dionysia, in March of the year 468, was not only remarkable for the victory of twenty-seven year old Sophocles over the honoured and battle-scarred Aeschylus, who was now approaching sixty. There was something else. Owing to the excitement which the competition between youth and age had aroused, the official whose duty it was to appoint the judges had not yet dared to do so. He was about to solve the problem in the way Athens solved many problems — by drawing lots — when Cimon, an aristocrat, politician and admiral, entered the great open-air …

Read More »Aeschylus

Play-acting had been developing at Athens since Peisistratus had introduced the Dionysia and the Panathenaea festivals; but to call it play-acting in the early stages gives a false impression. It was more like open air opera and ballet with a strong religious flavour. Originally there was a “chorus” of fifty men who chanted and danced in a dignified way. In the intervals an actor recited. Aeschylus added a second actor and the two actors, as well as conversing with each other, conversed with the chorus or its leader. All wore masks and impressive robes. Several plays were performed one after …

Read More »“Wooden Walls” and Salamis

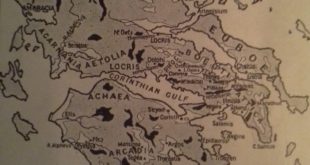

After Thermopylae the Spartans were only interested in defending the Peloponnese. Their next line of defence was across the Isthmus of Corinth. The atmosphere on the two sides of that line was now very different. Much of the Peloponnese was still far from the war. At Olympia the four-yearly games were taking place as usual. (Who on earth was free to attend them? one wonders.) North of the Corinthian gulf, however, townsmen and countrymen alike knew that the Persian army would be on top of them any day now. Knowing this, what did they do? The men of Delphi routed …

Read More »Thermopylae

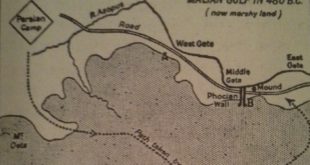

The first narrow place where the Persians might have been held was the pass of Tempe in the north of Thessaly. A force was sent there but withdrew when news came that the Persians might take another route and outflank them. Thessaly was thus abandoned to the Persians; but they were not to be allowed farther south without a fight. The only route lay through the pass of Thermopylae. Here Leonidas the Spartan, who was Commander-in-Chief of the Greek forces, decided to make a stand, while the combined Greek fleet kept watch near Artemisium on the Persian ships, which were …

Read More »The Second Persian Invasion

Darius I died in 486. In the last years of his life he had no need of the slave who had whispered. “Sire, remember the Athenians.” He remembered Marathon all too well and was making preparations for another attack on Greece. These preparations were continued after Darius’s death by his son Xerxes. By the year 480 an enormous force had assembled at Sardis and a fleet was ready to sail in support. This “Persian” army and fleet was in fact made up of contingents drawn from all over the vast Persian Empire, including Ionian Greeks. The march out of Sardis …

Read More »The Rivals

After a battle there is a great deal of clearing up to be done. A small part of the Athenian force had been left behind to do this. The general in command was Aristides. “The Just”. There was no fear of his taking any of the rich Persian spoil for himself. He had gained a reputation for scrupulous honesty, for putting country before self and for modest behaviour. These qualities were rare. Perhaps as he returned to the Athenians after completing his task at Marathon, he felt that he had a good chance of occupying a powerful position such as …

Read More »