So much for the legend. What of the facts?

At Cnossos, near Herakleion, in Crete are the ruins of an enormous palace, which must have needed somebody like Daedalus to design it.

Its honeycomb of cavernous cellars, traces of which still remain, might well have given rise to stories of a “labyrinth” and though no pictures of the Minotaur himself have been found, bulls occur frequently in the paintings which can still be seen upon the palace walls.

Sir Arthur Evans began to excavate this great palace in 1899 and called it “The Palace of Minos”. He did not find evidence that a king called Minos had built it. Minos remains legendary, but the name was dignified and convenient.

From excavations at Cnossos and elsewhere in Crete, it has been possible to trace the history of Cretan civilization back to about 3000 B.C. So it is here, not on the mainland, that a history of Greece ought to begin.

Crete is only 180 miles from the coast of North Africa, along which ships could sail to Egypt. Archaeologists have been able to show that Crete did in fact have links with Egypt as well as with the ancient civilizations of Asia Minor and Mesopotamia. A copper axe found at Cnossos shows that Crete probably received copper from Egypt as early as 3000 B.C. and the Cretans later learned pottery and other arts from the Egyptians.

By 2000 B.C. Crete was a highly civilized country. Writing, to which dogged scholarship has only recently found the key, had been developed; but as there were no papyrus marshes, clay tablets were used. The pottery and metalwork industries had made a thriving foreign trade possible. The first palaces had been built and much of the island was united under one line of Kings.

The years 1600 to 1400 B.C. were the golden age of Crete. It is to this period that the Palace of Minos belongs. It was big and brightly painted, with an efficient water supply and drainage system. The great town of Cnossos, of which this palace formed the most elegant part, may have contained about eighty thousand people (i.e. it was comparable in size to Exeter, Cambridge or Motherwell).

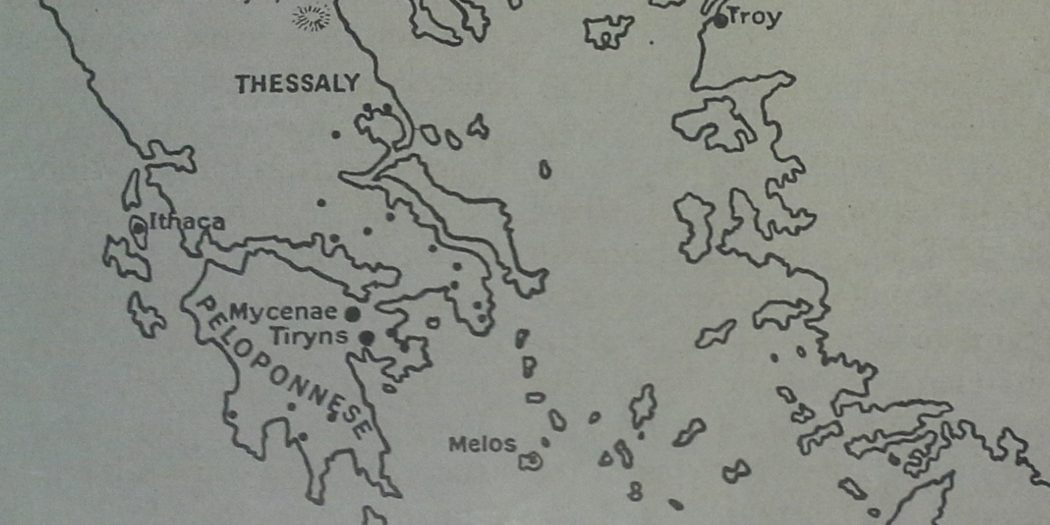

After 1400 B.C. the power of Crete declined and by about 1200 supremacy in the Aegean had shifted to the mainland — not to Athens, but to the cities of Mycenae and Tiryns in the Peloponnese. Their inhabitants, the Achaeans, had learned from the Cretans to make fine pottery and metalwork and to put up big stone buildings, but they also surrounded their cities with massive walls, which the Cretans had never built, since they relied upon their fleet for defence.

The Achaeans of this time, however, are remembered in history as besiegers rather than besieged. It was they who fought against Troy. Once again, where legend is mixed with fact, it will be best to begin with the legend.