Like Gandhi and Nehru in India, one of China’s greatest leaders, Dr. Sun Yat-Sen, learned from the West as well as the East. Born in 1867 of a Christian family, he received most of his education in Hawaii; while an exile, he lived in Europe, America and Japan. Although Dr. Sun had been educated to be a surgeon, he soon gave up the practice of medicine to lead his people against their Manchu rulers. The Chinese were successful in overthrowing the Manchus and in 1912 they proclaimed their country a republic. Dr. Sun, who became known as the “father of the Chinese revolution,” was named president, but he turned the office over to Yuan Shih-kai, a general who had a number of followers. Dr. Sun believed that Yuan would be better able to keep order and unify the country. Instead, Yuan made himself a military dictator and when he died in 1916, China was more divided than ever. Local war lords, or military governors, controlled the provinces. Each of the war lords had his own soldiers, collected taxes and ruled his territory as he pleased. Seeking for a way China could become a free and independent nation, Dr. Sun worked out his “Three Principles of the People‚” or, in Chinese, San Min Chu I. The first of the three principles was nationalism. Chinese society had always been based mainly on the family; now the Chinese must think of themselves as a great and unified nation with a long history of civilization. They must rule themselves and have the same power as other nations. They must stop giving concessions and special privileges to foreigners and they must do away with the war lords. The second principle was democracy. The government and the people must be responsible to each other. The people …

Read More »The Powers Carve Up China 1841 – 1914

China, that immense portion of East Asia bounded by the chilly Amur River and the hot jungles of Indo-China, by the Pacific Ocean and the Himalaya Mountains, was the most populous country on earth. For thousands of years, China had had a highly developed civilization. Its people thought of their land as the world itself; to them, it was the Middle Kingdom between the upper region, heaven and the lower region, hell, which was made up of all other lands. They considered foreigners nothing but barbarians. Only a few Europeans had entered China since the Middle Ages and the Chinese had scornfully refused to trade with them. The Europeans remembered China, from accounts like those of the Venetian traveler Marco Polo, as a land of fabulous wealth. They longed to lay hands on this wealth and during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the imperialist powers managed to get some of it. Despite its size, China was very weak. In the family of nations it was like a fat old grandfather whose head was so full of old-fashioned actions that he could not understand the boisterous young people around him. The old man was sick, too — with “internal disorders.” For the Chinese were more and more discontented with their Manchu emperors. The Manchus were the latest imperial dynasty in a line stretching back over two thousand years. Their ancestors from Manchuria had conquered China in the seventeenth century and many of their subjects still thought of them as foreign barbarians. From time to time, the Chinese rebelled against them and tried to drive them out. China had troubles of its own even before the foreign imperialist came. The greatest uprising against the Manchus was the Tai-Ping Rebellion of 1850. Twenty million people died — as many as lived in …

Read More »The Ming Dynasty Restores the Old Order A.D. 1368-1644

THE MEN who took over from the Mongols came to be known as Hung-wu, or “Vast Military Power.” Hung-wu named his dynasty ming, or “brilliant.” As things turned out, however, the Ming dynasty was not particularly brilliant. It was, in fact, humdrum compared to the Han, the T’ang, or even the Sung. Nevertheless, it gave China nearly three centuries of order, from 1368 to 1644. Hung-wu was born in a hut near Nanking in 1328. His parents soon died and the boy entered a Buddhist monastery, where he learned to read and write. His studies completed, he went out into the streets and begged for a living. Then, at twenty-five, he joined a band of rebels. Through character, intelligence and energy, he became its leader. In 1356, he captured Nanking from the Mongols and then, little by little, occupied the entire Yangtze Valley. In 1368 at the age of forty, he seized Peking and proclaimed himself emperor. THE TRIBUTE SYSTEM Hung-wu chose Nanking as his capital. At first he ruled through government departrnents, but as time went on he treated his ministers more and more contemptuously. In 1 375, he had one of them publicly beaten to death with bamboo sticks. Five years later, suspecting his prime minister of plotting against him, he abolished the office and took all state business into his own hands. The older he grew, the more distrustful he became. Fat and pig-like, with tufts of hair growing out of his ears and nostrils, Hung-wu was a sad and lonely man all his life. His personality was so commanding and his achievements so vast that after he died in 1398 nobody could forget him. His successors tried to copy his one-man government. Like him, they had officials who displeased them beaten, tortured and killed. Next to …

Read More »The Sung Dynasty: Barbarians Threaten the Empire A. D. 960 – 1279

DURING THE turbulent Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms era, the main outside threat to China came, as usual, from the north. A tough Mongol people from Manchuria helped one of the Chinese Warlords conquer North China. In return, he let them settle around Peking. Some of them became farmers, but their nomadic habits of roving and fighting remained strong. From time to time they raided the North China Plain, striking terror into the hearts of the peasants. These troublesome people were called the Khitan. Another form of their name, Khitai, sounded like “Cathay” to European travelers who later came to China. Throughout the Middle Ages, China was known in Europe as Cathay. In 960, the ruler of north China sent his best general after the Khitan to teach them a lesson. Instead, the general seized power and proclaimed himself emperor. As founder of the Sung dynasty, he was later called T’ai Tsu, or “Great Beginner.” Before he died in 976, he conquered most of China. His brother T’ai Tsung — “Great Ancestor”– conquered the rest, except for the Khitan kingdom in the northeast. The Sung dynasty was to reign until 1279. A1though it started out boldly, it never became as powerful as the Han and T’ang dynasties. One reason was that the emperors deliberately kept their army commanders short of men and money to make sure they did not revolt. As a result, the empire was constantly menaced by barbarians. In the end, it was destroyed by them. For generations, the Sung emperors bought peace by bribing the Khitan and a northwestern barbarian nation called the Hsi Hsia. Then a third barbarian nation entered the picture. In 1114, Manchurian nomads who called themselves the Chin, meaning “Golden,” attacked the Khitan. Seeing a chance to recover the long-lost northeast territory, Emperor …

Read More »Christian Knights and Mongol Horsemen A. D. 099-1404

THROUGHOUT THE eleventh century, the divided Arab Empire became weaker in all its parts. Meanwhile, the Christian lands to the north became stronger. Adventures from northern France snatched Sicily and Southern Italy from the Arabs. The pope called on the rulers of Europe for a united Christian attack on the Moslems. By the end of the century, European knights in chain-mail armour were streaming into Syria by land and sea, determined to recapture the holy places of their religion. This campaign was the first of many. The Crusades dragged on for two centuries, with long periods of peace coming between bouts of fighting. Christian kings and noblemen carved small states out of Moslem territory, only to lose them. In 1099, Frankish troops seized Jerusalem, the Christians’ holy city, and made it the capital of a kingdom. In 1187 Saladin reconquered the country for Islam. After the Moslems forced the last Crusaders to leave Syria in 1291, only the island of Cyprus remained under the Christian flag. So, in the end, although the Crusades did not change the balance of power between Christianity and Islam, they left behind bitter memories which were to poison Moslem-Christian relations for centuries. Not all of the results were bad, however. The Crusaders, who came to the Near East convinced of their own superiority, found that their despised enemies knew more than they did about a great many things. They took the knowledge they had gained home to Europe. The brave deeds of the warriors on both sides gave rise to thousands of poems, songs and tales which enriched the literatures of Europe and Islam. The Christian heroes included two kings — Richard the Lion Hearted of England and Louis IX of France, who was made a saint. Among the Moslem heroes, the most famous were …

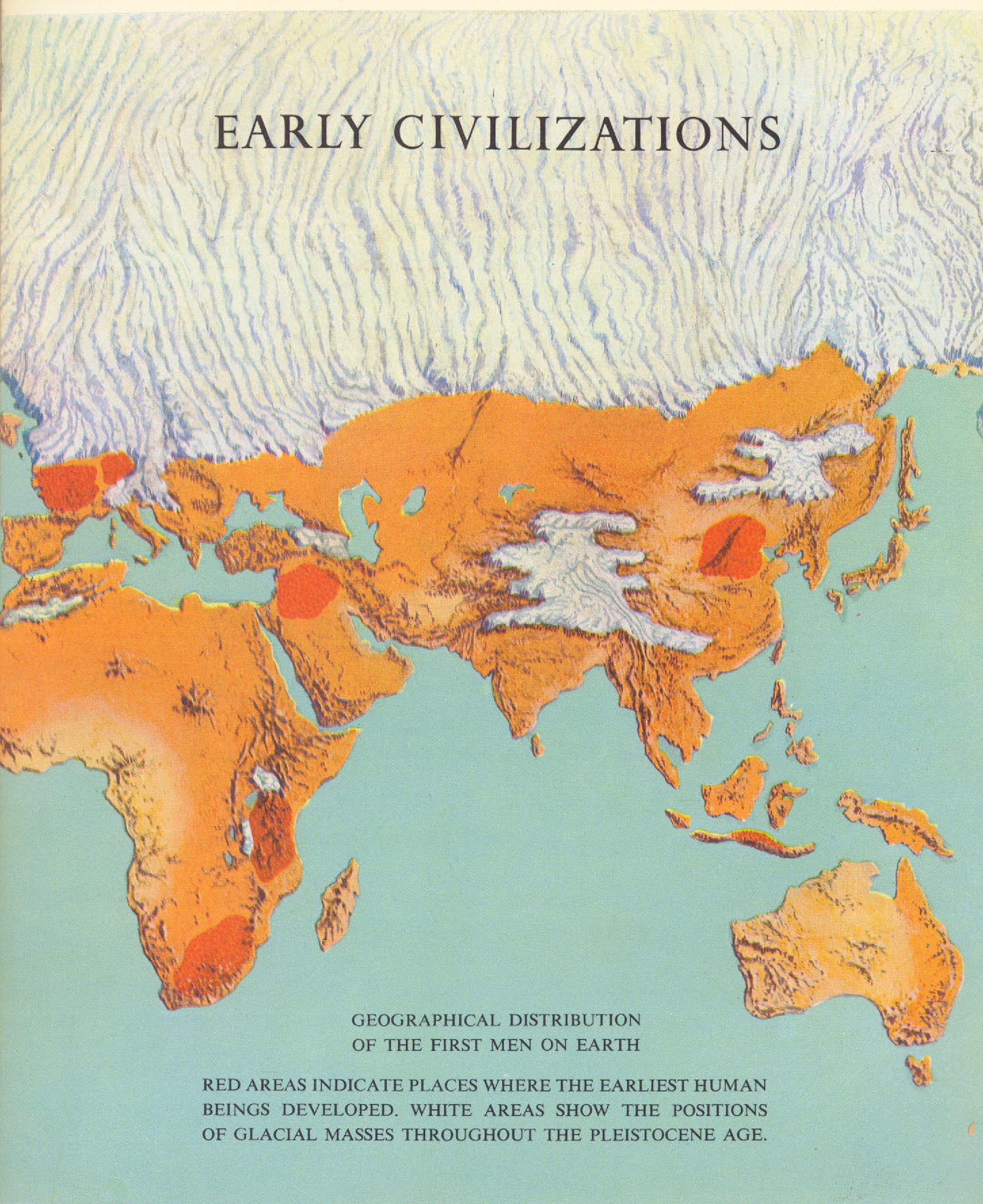

Read More »The Coming of Man

About 400,000 years ago, a group of people were gathered at the mouth of a cave. They had a fire in which they were roasting deer meat and around them lay the bones of monkeys, wild pigs and water buffalo from previous meals. One of the women was picking berries from the nearby bushes. A man sitting close to the fire chipped away at a broken stone he would use to cut off chunks of the cooked meat. Another man, too hungry to wait, gnawed the marrow from some bones. The cave was one of several not far from what is now Peking, China and the people who first used these caves are known as Peking Man. Peking Man did not leave anything behind except some bones, charcoal, berries and stones, but these are enough to suggest certain things about the way he lived. They show that the people at the caves ate meat as well as plants, made crude tools, could kill large animals and knew how to keep a fire alive. With fire they could keep warm and fend off wild animals at night. Probably they cooked some foods in the fire. Instead of eating in the fields after killing an animal, the men might wait until they gathered around the fire to eat. Such a meal became something of a family or group occasion. There was a sharing of tasks, of food, of pleasures. No one said much, but with simple language the adults could pass on something of what they had learned to their children. At times, when food was scarce these people may have eaten human flesh, but it is likely they killed only to survive. Or perhaps they believed by eating human flesh they could obtain the strength of a slain enemy, or keep …

Read More »