Alexander the Great succeeded to the throne upon the assassination of Philip of Macedonia, in northern Greece. This succession, both as king and as leader to the League of Corinth, was his twenty-year-old son Alexander. In addition to the throne, young Alexander inherited his father’s mission to take revenge on the Persians on their own ground. The fulfilling of that mission and its consequences constitute one of the most glittering pages in the history of the ancient world. Alexander may not have wanted to fuse the traditions of East and West in the empire he created, but he gave Hellenism to posterity, thus bequeathing a truly international culture for the civilized world.

Twelve years had passed since Alexander, the young king of Macedonia and captain-general of the League of Corinth, had stood at the helm of his ship, guiding it over the Hellespont to the shores of Asia — twelve years and twenty thousand miles of Asian roads. Now, in 323 B.C., in a world that he himself had shaken and transformed, he lay dying in his Babylonian palace, and at the doors the soldiers clamoured to see their leader. The rumour had spread that Alexander was dead already and that his death had been concealed by the guards. At last the doors were thrown open to the rough horsemen and pikemen of Macedonia; with bewilderment on their faces, they crowded silently past the king’s bed. Alexander was in his last fever, beyond speech and almost beyond life, but he made the effort to raise his yellowed face and nod some kind of greeting.

That night his generals — Seleucus and Peucestas, Peithon and Cleomenes — went to the temple of Serapis and asked if they should bring their leader to the god, but the oracle answered that it would be better for him to remain in his palace. There, soon afterwards, Alexander died. His illness had been malaria, the last of many bouts he had suffered on his campaigns; but it was malaria assisted by heavy drinking and the fury of a man fighting against unaccustomed ill-fortune.

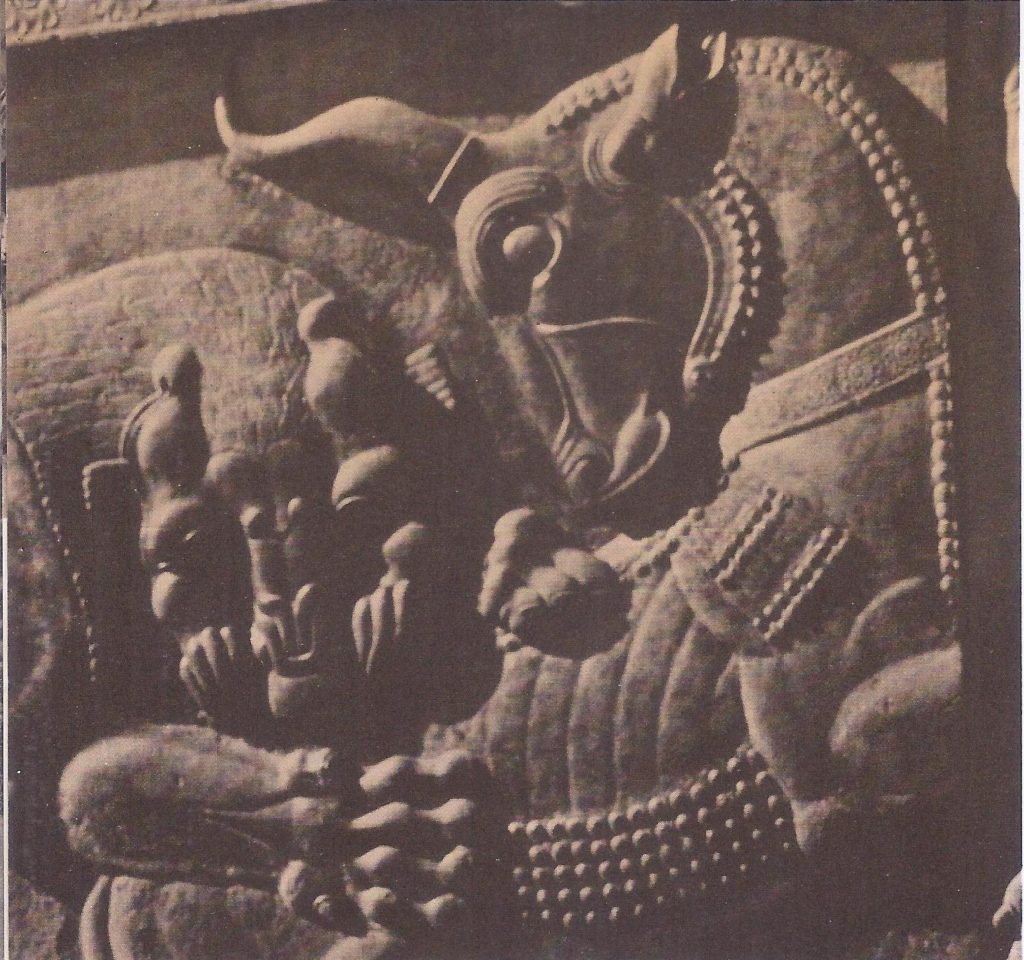

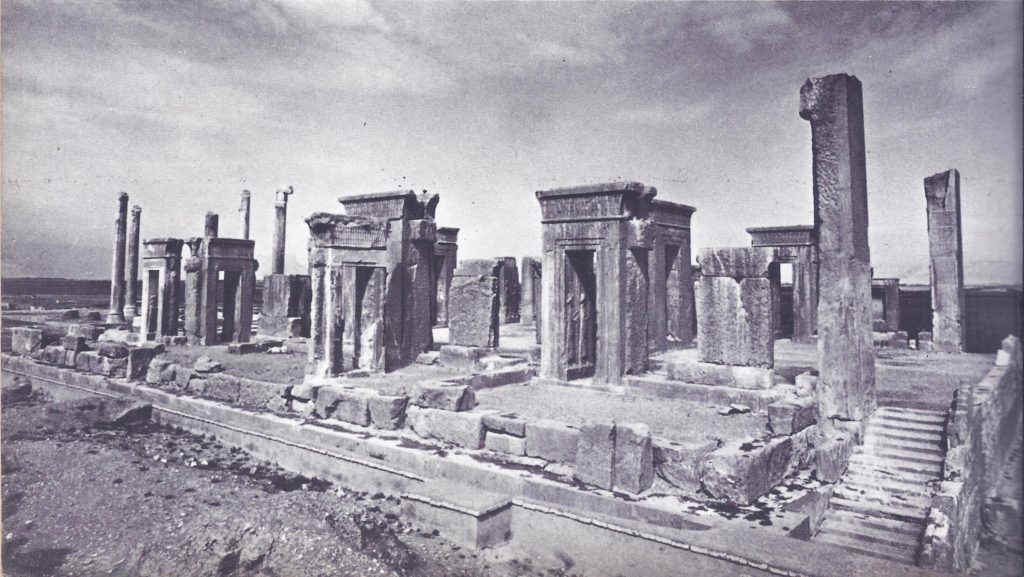

Alexander died only seven years after the king he had displaced on the throne of Persia — Darius III, last of the Achaemenid line founded by the great Cyrus in the sixth century B.C. For almost two hundred years, since the fall of the Ionian cities to Cyrus in 545, Persia and Greece had been intimately linked. Darius I had been defeated at Marathon in 490, Xerxes and Salamis in 480 and Plataea in 479. Persians however, still ruled over Greeks in Ionia and by playing upon the rivalry between Sparta and Athens, they contrived to interfere in the affairs of the Greek states in Europe. Greeks sold their services to Persia, as mercenaries and craftsmen; they helped to build the great palaces at Susa and Persepolis; and as the Persians themselves grew soft from easy living, the paid Hellenes gradually became the most reliable corps in the vast and unwieldy army of the Persian King of Kings.

Accepting Persian pay, the Greeks observed Persian weaknesses. The epic story of the Ten Thousand — the Greek mercenaries who alone in the army of Cyrus the Younger, stood firm at the battle of Cunaxa in 401, then fought their way to the Black Sea — became not only a literary classic in the hands of Xenophon, but also an inspiration to more ambitious men. King Agesilaus of Sparta was certainly not without hopes of considerably reducing the Persian domain in Asia Minor and periodically the Athenians thought of revenge when they remembered how Xerxes had desecrated and destroyed their temples.

The great Attic orator Isocrates preached not only the union of the Hellenic world, but also a crusade against Persia, the natural enemy of the Hellenes. When he saw no one among the Greeks would heed his opinion, he looked to Philip II of Macedonia, a Hellenized barbarian who claimed descent from Achilles, Hercules and for good measure, Perseus. Philip aspired to become the protector of neighbouring Greece and in 338 the League of Corinth entered into an arrangement for mutual defense with him and appointed him captain-general of the joint Greek and Macedonian armies. Philip persuaded the League to approve a war against Persia; before he could lead it, however, he was killed by an assassin. In 336 his son Alexander, twenty years old, succeeded to the throne of Macedonia and the captaincy of the League.

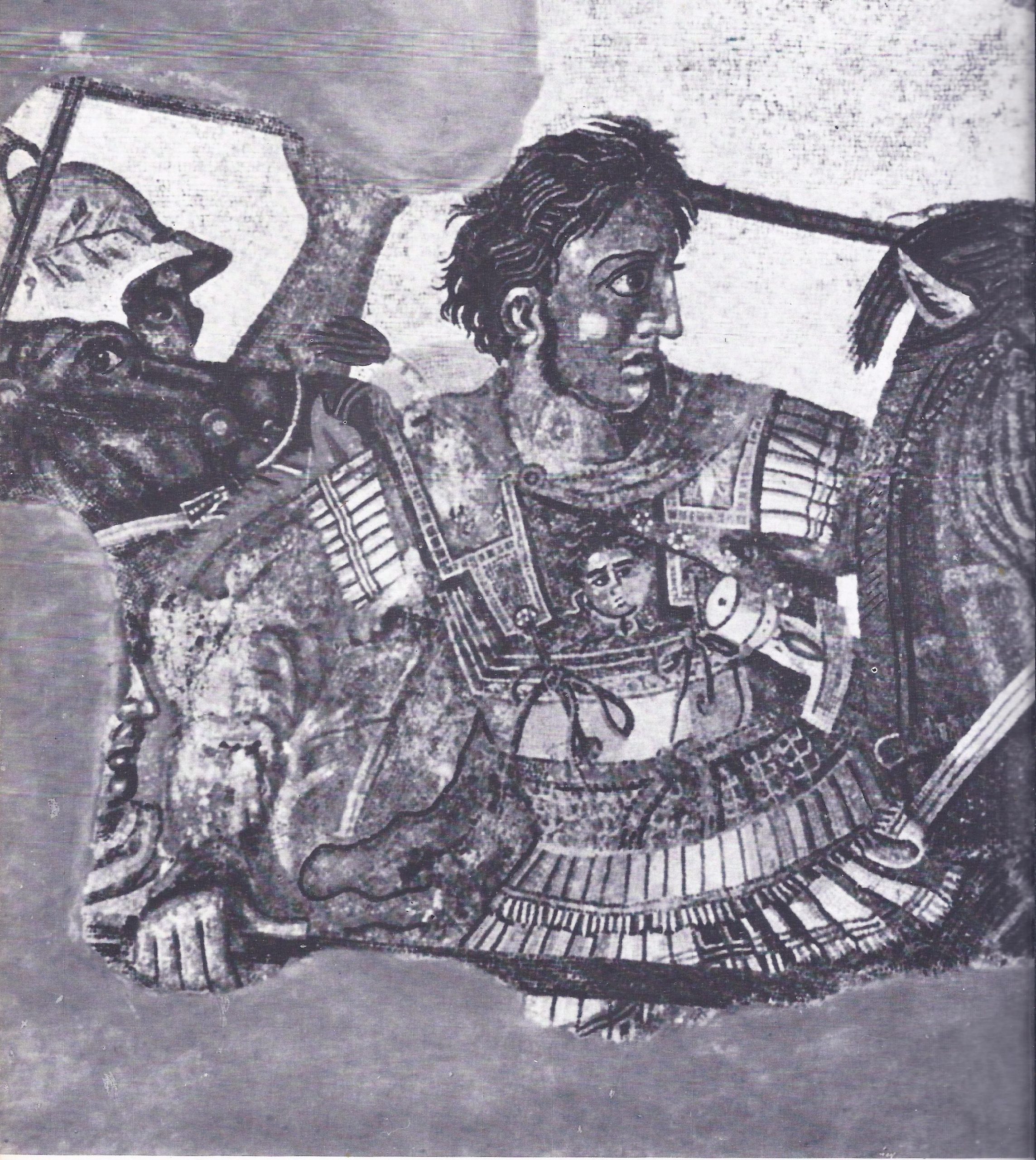

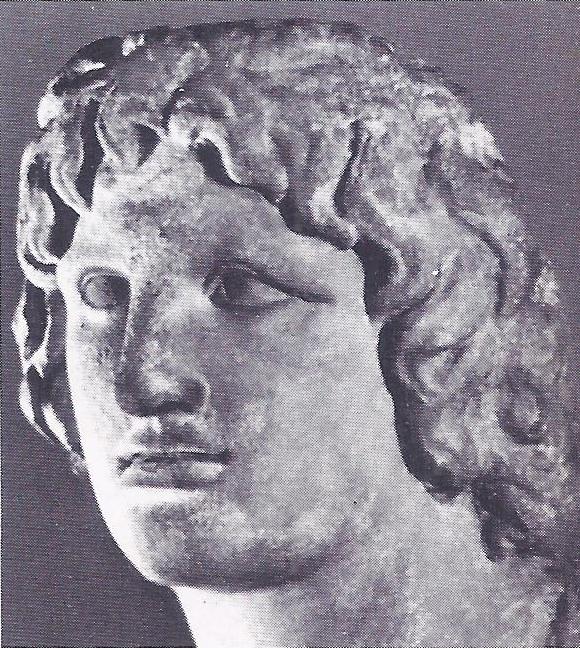

Never has any man been more fitted for his hour — an hour that offered a whole world to conquer and remake. Alexander’s phenomenal beauty may be a legend fostered by flattering artists and chroniclers; but of his genius there can be no doubt. His strategic vision, his tactical originality and his grasp of military engineering are too well known to warrant discussion. From the beginning, the savage courage of Alexander the warrior was balanced by other, more humane forms of audacity. The influence of Aristotle, his childhood tutor, had not been in vain. Alexander’s ruthlessness was Macedonian, but his intellectual curiosity and tolerance were Hellenic. More than any other great man of action, with the exception of Pericles, he represented the questing Greek mind. He became a great explorer and the inspirer of generations of geographers. In planning his expeditions he included philosophers, naturalists and topographers as well as military engineers. “If I were not Alexander, I would like to be Diogenes,” he is supposed to have said. It is this combination of conqueror and philosopher that makes Alexander so fascinating and so historically significant.

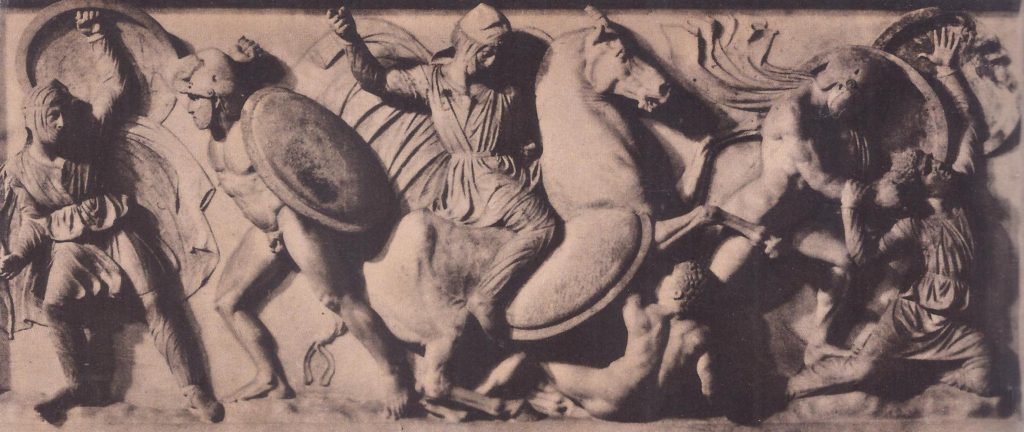

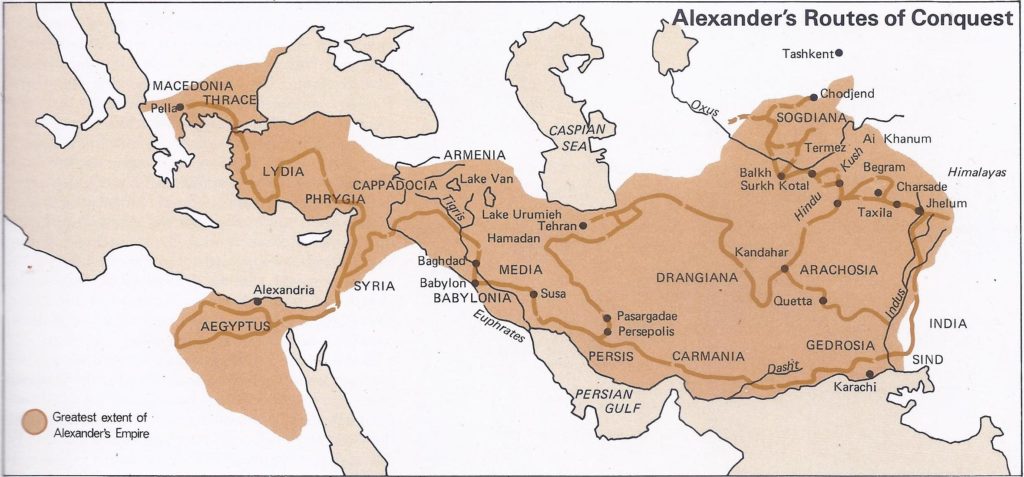

The story of his conquests is familiar. He set out in 334 from his Macedonian capital of Pella, which he was never to see again. Crossing to Asia Minor, he defeated the Persians at the Battle of Granicus and liberated the Ionian cities. Late the next year, campaigning down the coast of Phoenicia, he defeated the main Persian army at Issus and put Darius to ignominious flight. Taking his time to besiege and destroy Tyre and Gaza, he proceeded to Egypt, acquired a legendary parent in the god Amon and showed off a new, constructive side to his leadership by founding the first and greatest of all the Alexandrias, the queen city of the Hellenistic world.

Having consumed in such methodical fashion the western perimeter of the Persian empire, Alexander next aimed a blow at the heart. In the autumn of 331 he marched into Mesopotamia and met Darius on the field of Gaugamela. The elephants and the scythe-armed chariots of the Persian king, the multitudes of warriors he had drawn from every distant corner of the Achaemenid dominions, were of no avail against Alexander’s cavalry and the Macedonian phalanx.

Totally defeated, Darius fled into the depths of Bactria; Alexander proceeded as conqueror to Babylon and Susa, then eventually to Persia proper, the centre and birthplace of Darius’ power. At last Alexander sat on the throne in the palace Persepolis, built by Ionian craftsmen. The champion of Greece was transformed into the Great King of Asia, yet without entirely ceasing to be the champion of Greece. From then on the effort to reconcile his Hellenism with his Oriental power became the overriding element in Alexander’s life.

The campaigns continued. Darius, pursued into Central Asia in a series of extraordinary marches was killed by his own general, Bessus. Bessus and other Persian captains were slaughtered or incorporated into the Alexandrian pattern of government. Then, in 327, Alexander launched an expedition to India.

It was at this point that Alexander’s incredible run of luck was reversed. Ironically, the frst defeat of his life came at the hands of his own men. In 326, on the bank of the Jhelum River in India, his troops refused to pass beyond the Punjab into the lands of the great kings who ruled in middle India. “A commander like you, with an army like ours,” his general Coenus said to him then, “has nothing to fear from any human enemy; but remember fortune cannot be foretold, and no man may protect himself from what it will bring.” Fortune had taken Alexander to the throne of the Achaemenid King of Kings in Persepolis, to the heartlands of Central Asia where Samarkand and Bukhara would later rise — and over the Hindu Kush in search of the great River of Ocean which he imagined washed the foothills of the Himalayas. After the events on the Jhelum, he turned reluctantly back from the Punjab to fight his way down the Indus Valley, nearly dying from an arrow that pierced his lung when he assaulted the fortress of a fierce tribe in Sind.

There followed a terrible march over the desert of Gedrosia, with men and beasts dying of thirst and Alexander sharing the privations his infantry endured. On his return to Babylon he found that many of the men he had left in charge had taken advantage of his absence in India to plunder the people and desecrate monuments. It was bad enough that Persians, who were indebted to him for his clemency, should do this; it was more bitter news to hear that Harpalus, his companion since childhood, had plundered the Persian treasure and then had lied to evade Alexander’s wrath, dying at the hands of a fellow robber on the way back to Greece. Then, at Opis, there had been a mutiny by the Macedonian veterans, whom Alexander proposed to send home and replace by Persian levies; thirteen of his men were executed for that revolt. Finally his beloved friend Hephaestion had died in Ecbatana — perhaps also of malaria — and Alexander had abandoned himself to a prolonged and immoderate grief.

The Savage Courage of Alexander the Great

From all these misfortunes, Alexander emerged in the spring of 323 to plan an expedition that would revive his military glory and satisfy his perennial longing to know the unknown. To explore and subdue Arabia, a region little known even to the Persians, would make up for his failure to conquer India. A great harbour to hold a thousand ships had been dredged beside the Euphrates and fleets had been assembled and manned by Phoenician and Ionian sailors. Troops had been recruited in Persia, Lydia and Caria; it would no longer be a Macedonian army that Alexander led, but an army of all the peoples under his rule. June 7, 323, was fixed for the start of the expedition. Five days before the scheduled departure, Alexander performed sacrifices to assure his success, gave wine to his men and drank heavily with his friends. Medius, his favourite since the death of Hephaestion, induced him to continue drinking late into the night and before he went to sleep, the fever had already seized him. During the next few days Alexander insisted on continuing his sacrifices and giving orders to his army officers and to Nearchus, his admiral. However, his condition became grave and he was carried to a summer house beside the river and finally to his palace. By this time he had lost the power of speech. Eleven days after the outset of his fever he died, at the age of thirty-three. The expedition to Arabia was never undertaken.

Revenge on Persia

During his lifetime Alexander and his empire remained a disturbing enigma to his Greek and Macedonian followers. Remembering the leader who stood at Issus and exhorted his men with the cry, “We are free men, they are slaves,” the Greeks were puzzled when Alexander tried to introduce into his court the Persian custom of prostration before the throne. When the sophist Callisthenes openly voiced his disapproval, he died — no one knows how — as a martyr to his own philosophic candour. Alexander’s companions murmured angrily when the conquered Persians were welcomed as equals at the court. Finally, one night, after drinking heavily, the king quarreled with Cleitus, who had saved his life at the battle of Granicus and killed him. The division between the ambitions of Alexander and the reservations of his followers put an end to the Indian expedition and sparked off the mutiny of Opis. After Alexander’s death, there would be many Hellenes to claim that he turned away from Greece and became an Oriental ruler.

In a way, this was true. One can even mark a turning point at Ecbatana, in the spring of 330. when Alexander dismissed as allies the Greek soldiers of the League and retired as mercenaries those who chose to stay.

His role as captain-general of Greece was discarded; now he claimed the Persian empire as his by right of Conquest. Already, that winter, he had begun to fill his army with Persian recruits, trained in the Macedonian manner. In 325 he arranged an inter-racial mass marriage festival at Susa. Alexander had already in 327 married a Persian princess, Roxana, daughter of the Bactrian Chieftain Oxyartes. Now he chose as a second wife the daughter of Darius, persuading eighty of his closest companions to pick Asiatic wives and ordering ten thousand soldiers to do likewise. Later, after the mutiny of Opis, there was a festival of reconciliation attended by nine thousand people; led by Greek priests and Persian Magi, the assembled guests prayed that the Macedonians and Persians might rule the empire together in true harmony.

For the claims that have been made that Alexander was the first ruler with a truly international vision, there is little further evidence. Diodorus Siculus, writing as a contemporary of Julius Caesar, certainly saw Alexander as believing in a real union of the people of Asia and Europe, but his view of history was necessarily influenced by the Stoic and Epicurean egalitarian ideas. It is difficult to argue against historians who claim that Alexander conceived not a true internationalism, but merely a renovated Persian empire, streamlined by Greek logic, Greek efficiency and ruled by a dual master race.

What did Alexander plan for the physical extension of his empire? He had already won the greater part of the antique world. After Arabia he hoped to conquer the lands around the Caspian Sea. He had left garrisons in the Punjab and at the mouth of the Indus and there is little doubt that one day he meant to complete the conquest of India. We can only speculate about his plans for the Mediterranean, but the fact that the Carthaginians, the Etruscans and even the far Iberians sent ambassadors to congratulate him on his conquests suggests an unseemly rush to make terms before his deep-eyed look turned westward. Writing his history of Alexander’s expeditions, in the second century A.D., Arrian speaks of his “insatiable desire to extend his possessions” and it is unlikely that, if he had lived, he would have left unattempted the conquest of Italy, France and Spain, where the Greeks had already long established colonies. His eventual aim was almost certainly to unite under his own rule the whole of the known world.

The Legacy to the World

Alexander profoundly affected the world through which he passed. At his death his empire was frozen within the boundaries he had created and the only later extension of Hellenistic rule was in the eastern marches where he had merely conquered and passed on. Two centuries after his death the Greek kings of Bactria sent their cavalry probing toward the boundaries of the Chinese empire and in the middle of the second century B.C. Menander, the Greek king of the Punjab and a philosophic warrior of the same temper as Alexander himself, fulfilled his predecessor’s ambition by leading an army of Greeks and Persians down the valley of the Ganges to capture Pataliputra, the capital of Hindustan.

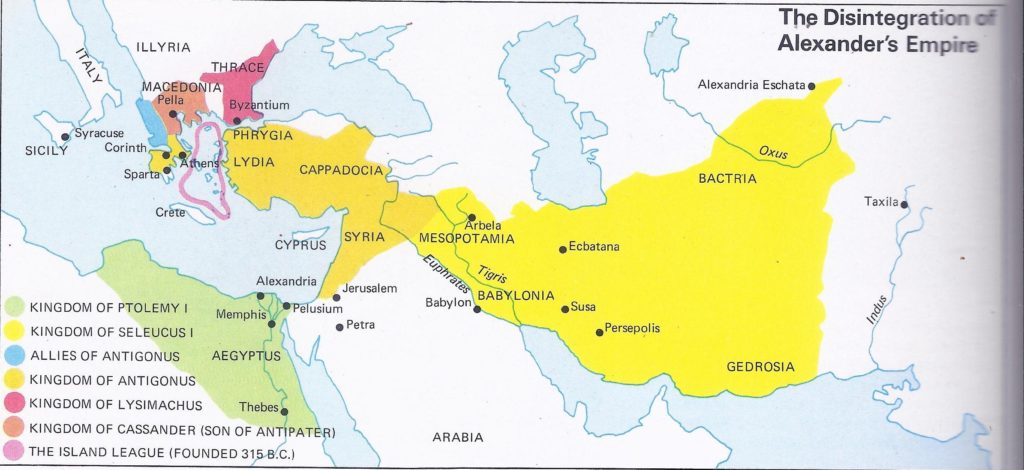

After Alexander’s death, his empire fell immediately into disunity. His heir was Roxana’s yet unborn child, the unfortunate Alexander IV, who was eventually murdered in 311 by Cassander son of Alexander’s general Antipater. Antipater was nominal regent; in fact Alexander’s generals known as the Successors — Seleucus, Ptolemy, Antigonus, Lysimachus, Eumenes — divided the empire. Ptolemy departed first to his satrapy of Egypt, taking with him the body of Alexander to bury it in Alexandria. In 306, when all the heirs had been eliminated, the Successors, or Diadochi, named themselves kings. Only one of them, Ptolemy, died peacefully in his bed; the rest were killed in the bitter struggles dividing them. For a while it seemed as though Antigonus might reunite the empire, but Ptolemy and Seleucus were strong for him and the Hellenistic world remained divided between three great kingdoms — Macedonia, under the descendants of Antigonus, Egypt under the Ptolemies and Syria, embracing also Persia and Mesopotamia, under the Seleucids. Smaller realms like Pergamum arose under the shadow of these great kingdoms and new city states like Rhodes and Byzantium became commercial powers in their own rights.

Despite all this fragmentation, the Hellenistic age was a time of vigorous civilization. It has been given too little credit for its achievements because historians have concentrated on its divisions and the dramatic decline of its kingdoms in the face of the Roman threat. The Successors, in spit of their conflicts, ruled over a surprisingly homogeneous world. Asian kingdoms in Pontus and Bithynia and Cappadocia adopted the Hellenistic culture and political systems, even the Parthian and Scythian rulers, finding their way into Greek Bactria, became Hellenized.

It was not entirely the kind of empire Alexander may have envisaged. The Successors had no use for his visions of co-partnership between Greeks and Asians. Only Seleucus retained the Persian wife he had been given at the great marriage feast of Susa and the ruling castes of all the Hellenistic kingdoms consisted either of Greeks — with a dwindling proportion of Macedonians — or of Hellenized members of the native aristocracy. This elite inhabited its own enclaves, typically Greek cities with democratic constitutions and its settlements included people of all classes who migrated from the over-populated Greece of the third and second centuries. The native people remained in the villages and retained their own cultures, so a marked horizontal rift, which Alexander had probably not foreseen, developed between Greeks and Asians.

Yet, unlike the Romans, the Greeks of the diaspora never conceived a universal citizenship. They were citizens of their individual communities, subjects of the Greek kings, but the bonds that united a man in Alexandria of Egypt with a man in Alexandria Bucephala of the Punjab, were cultural and not political.

The most durable of the Hellenistic states were those that eventually made some compromise with the native cultures. By the beginning of the second century the main states were decaying fast; by the middle of the century Macedonia and the Seleucid kingdom had been overwhelmed by the Romans and the Greek kingdom of Bactria by the Sakas. The Ptolemaic kings, who had accepted a place in the Egyptian religious hierarchy and had turned Alexandria into a great intellectual meeting place of East and West, survived; so did the Greek kings in India with their Buddhist affiliations. In fact, Cleopatra, last of the Ptolemies and Hermaeus, last of the Indo-Greek monarchs, died at about the same time; the battle of Actium in 31 B.C. finally ended the political legacy of Alexander’s conquests.

Yet even at Actium only one aspect of Alexander’s heritage was destroyed. As Rostovtseff has pointed out, “the ‘romanization’ of the Hellenistic world was slight, the ‘Hellenization’ of the steadily expanding Latin world much more conspicuous.” Later, from the eastern Rome of Constantinople, the Hellenistic world helped to give Eastern Christianity its special forms. To India, Alexander and his successors gave much of its art — the techniques of building and carving in stone and the Gandhara style — and the concept of a united rule that Chandragupta adopted when he founded the Mauryan empire. Even the Arabs, who finally destroyed the Greek cities of the East, retained Hellenistic science. Through Rome, Constantinople and the Arab world, Alexander contributed something to the new West of the Renaissance. even to lands he never conquered. If he failed to unify the world politically, he helped to turn it into an intellectual community, particularly when one remembers how much the great religions of Christianity, Mahayanist Buddhism and Islam owed to the exchange of ideas between Europe and Asia that he so materially assisted.