On Sunday, July 12, 1789, the people of Paris learned that Necker, the popular minister, had suddenly been dismissed by the king. They could only guess at the king’s reasons for wanting Necker out of the way. It seemed clear enough that Necker’s dismissal had something to do with the recent arrival of Swiss and German troops in the Paris area. It was said that more troops were arriving every day. Why? People were almost afraid to guess at the answer.

The news of Necker spread quickly and angry crowds gathered in the streets. A young man named Desmoulins leaped to the top of the table and warned the people to arm themselves. He probably repeated many of the ugly rumours then circulating in Paris. The king was bringing in troops to destroy the Assembly at Versailles. The king had entered into a plot with the nobles to smash the revolution, massacre the patriots in Paris and become once again the absolute ruler of France.

Desmoulins drew a pistol and waved it above his head. “There is not a moment to lose,” he shouted. “We have only one course of action to rush to arms. . .”

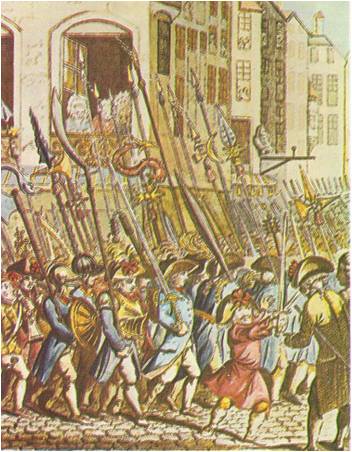

A growing crowd followed him through the streets. “Aux armes!” they cried. “To arms!” A regiment of the king’s German cavalry tried to scatter them and some of the people were slightly wounded. They screamed that they were being massacred and the crowd became a maddened mob. People armed themselves with sticks and pipes. They broke into the shops of gunsmiths to snatch up weapons. French soldiers left their barracks and joined them. The German cavalry, forced to retreat, hurriedly withdrew from the city. The police had also disappeared, leaving Paris in the hands of the rioters.

Under more normal conditions, the armed citizens and volunteer French soldiers might have been able to keep order throughout the night, but France was then suffering from a serious food shortage. Rainstorms and hail during the summer of 1788 had destroyed most of the grain crops in the countries of western Europe. The crop failure, together with the effects of a world-wide depression, had hurt business in towns and cities and caused many factories to close their doors. The result was that Paris was crowded with an unusually large number of unemployed workers and beggars, all desperate for food. Taking advantage of the confusion, they roamed the streets that night in gangs, breaking into shops to help themselves to food and anything of value they could carry away.

Businessmen and property owners became alarmed and demanded protection. Middle-class people representing the sixty election districts of Paris used the opportunity to set up their own city government and organized a militia of volunteers to keep order. With an army of their own they could defend themselves against the king’s foreign troops, if necessary.

Thousands of volunteers flocked to join the militia on July 13. The king’s foreign troops took up positions between Paris and Versailles, thus placing the Assembly in Versailles at the mercy of the king. Paris seemed to be surrounded by troops. Even the cannon on the walls of the Bastille, an old fortress on the east side of town, had been run into position and aimed at the city. During the night, rumours spread that troops were advancing upon Paris from several directions and panic swept the city.

On the morning of July 14, people rushed to guard the gates of Paris. They tore up cobble-stones from the pavements and piled them up in walls or breastworks across the streets to stand off the enemy. Such barricades could be built quickly and they became a familiar feature of street riots during the Revolution. The people wanted weapons with which to defend their city and they streamed from place to place in search of guns. At the Arsenal, they found nothing. At the Invalides, 32,000 muskets were passed out. Next they went to the Bastille, where it was said that a large supply of firearms was stored.

Built originally as a fortress‚ the Bastille had been a famous state prison for many years. Many tales were told of cruelty and horror within its great gray walls — tales of dark dungeons, of prisoners slowly dying of torture or being eaten alive by rats. No longer a state prison, it was used as an arsenal for the storage of weapons and ammunitions, but its evil reputation lingered on. Its gray rock walls were ten feet thick, with towers almost a hundred feet high. Moats filled with water surrounded the old fortress, making it impossible to reach the courts except by drawbridges.

A committee of three was allowed to enter the Bastille that morning to request arms and ask the governor to withdraw the cannon aimed at the city. The three were well treated and invited to stay for lunch. When they failed to return promptly, the crowd outside became excited and demanded the surrender of the Bastille. Somehow, two men managed to climb the wall and let down a small drawbridge. Angry citizens swarmed over it and into the inner court, while soldiers on the walls above fired down at them. Several persons were killed. The rest retreated, convinced that they had been tricked into entering the court so that they could all be slaughtered.

Everyone in the crowd who was armed began firing at the defending soldiers. In the one-sided battle that followed, only one of the soldiers was hit. The attackers’ losses were ninety-eight killed and seventy-three wounded. Twice during the battle the new city government sent delegates to put a stop to the fighting. When they approached the fort bearing white flags, they were fired upon and driven back by the soldiers on the walls.

The volunteer city militia and two detachments of French Guards then arrived with five cannon and began firing the heavy guns at the main gates of the fortress. The defending forces might have held out for many hours, but they suddenly became frightened and forced the governor to surrender the Bastille. The big drawbridge was lowered and the enraged mob rushed in with pikes, knives, hatchets, muskets and began slaughtering the defenders. A number of soldiers were killed before order could be restored. The governor was rescued and brought out, only to be killed by a mob on the street. His head was cut off and joyfully carried about the city on the end of a pike.

The Bastille had fallen — and when the people suddenly realized what they had done, they became frightened. They felt certain the king would quickly strike back with his army. One of them later wrote, “We all expected a fight with the regular troops, in which we might be slaughtered.” They did not know that the king too, was frightened. He had lost Paris and did not have enough troops near at hand to regain control of it. On July 15 he went before the Assembly and said that the future of the nation was now in the hands of the Assembly. He promised to withdraw his foreign troops at once, as he had been requested to do. The next day he also restored Necker to his old position in the council of ministers.

Lafayette, who had recently been made Vice President of the National Constituent Assembly, was appointed to head a delegation that was to carry the good news to the people of Paris. The delegation left at once. It arrived in the city to find a great crowd gathered before the City Hall. After Lafayette had announced that the king’s troops were being withdrawn, he learned to his surprise that the people had just elected him commander of the new city militia. Accepting the post, Lafayette raised his sword high above his head and promised to do what he could to save and defend “precious liberty.” A way opened before him through the crowd as he walked toward his carriage. The horses had been taken away. The people showed their devotion to Lafayette by picking up the traces of his carriage themselves and pulling him through the streets.

Lafayette later reorganized the militia, which became known as the National Guard. Its colors were red and blue, the colors of Paris. Lafayette added white, the color of royalty and provided each of his troops with a cockade, or knot, of three ribbons red, white and blue. This cockade was adopted by the French as the symbol of the revolution.

The fall of the Bastille, in itself, had no great importance, but to Frenchmen it suggested the end of all the evils they had suffered under kings and the beginning of an age of justice and liberty. The people of Paris tore down the Bastille stone by stone, as if to make certain of their newly won freedom. To celebrate the event, Lafayette sent one of the keys of the Bastille to his friend George Washington, the President of the United States. The date of the fall of the Bastille, July 14, soon became the great national holiday of France.