Latest Posts

Toledo falls, marking the end of Islam in Spain (1077 – 1100)

Toledo falls and this marks the beginning of the end of Islam in Spain. A triumph for orthodoxy The events

Henry IV, Humiliation at Canossa (1077 A. D.)

Henry IV stood barefoot in the snow, for three days in January, 1077, outside Canossa castle, waiting to see Pope

Pope Leo IX (1066 – 1077)

Galilee Chapel in Durham Cathedral. Durham was the greatest of the Norman ecclesiastical border fortress in the north of England.

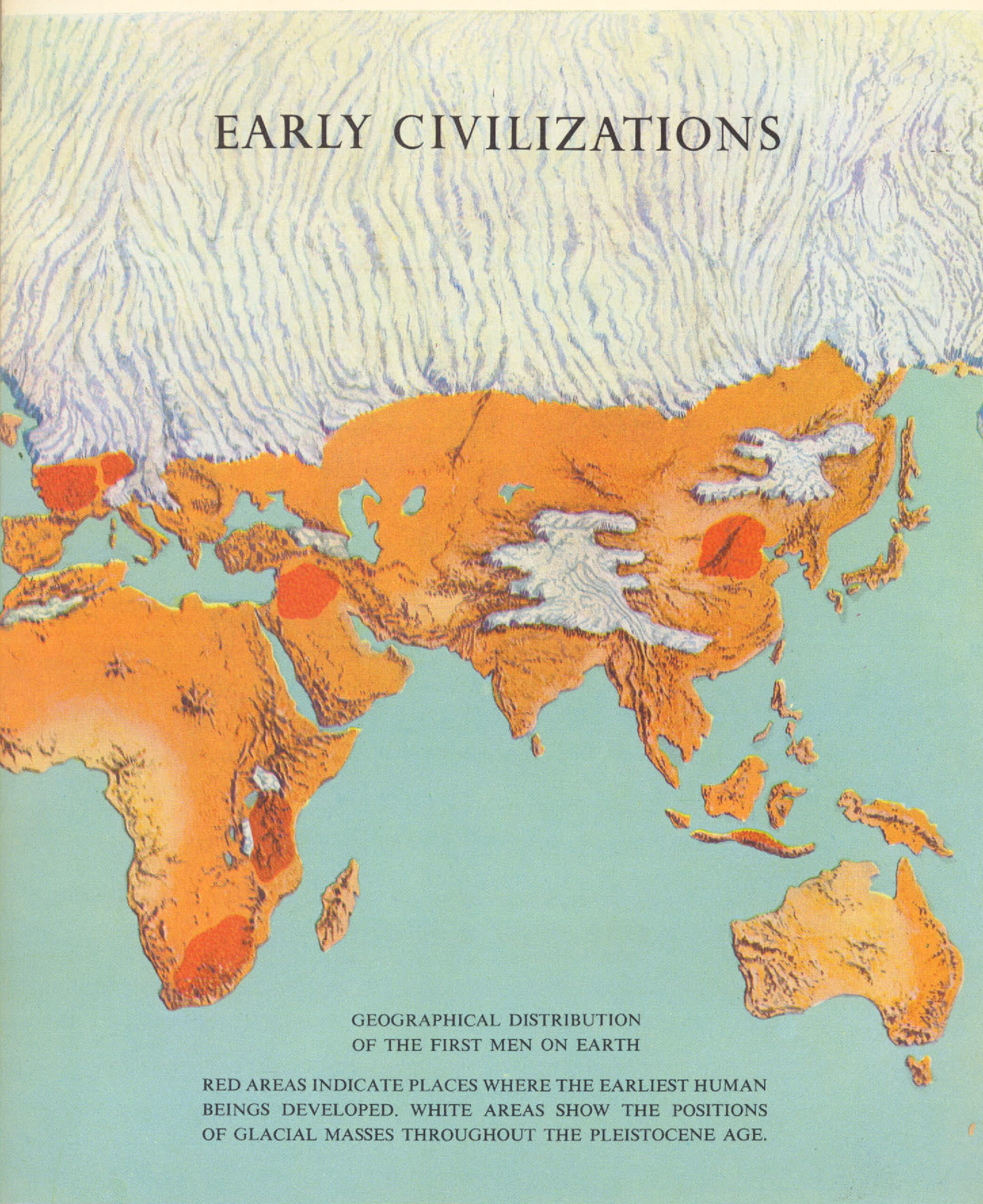

Early Civilizations to Modern Age

The Coming of Man

About 400,000 years ago, a group of people were gathered at the mouth of a cave. They had a fire

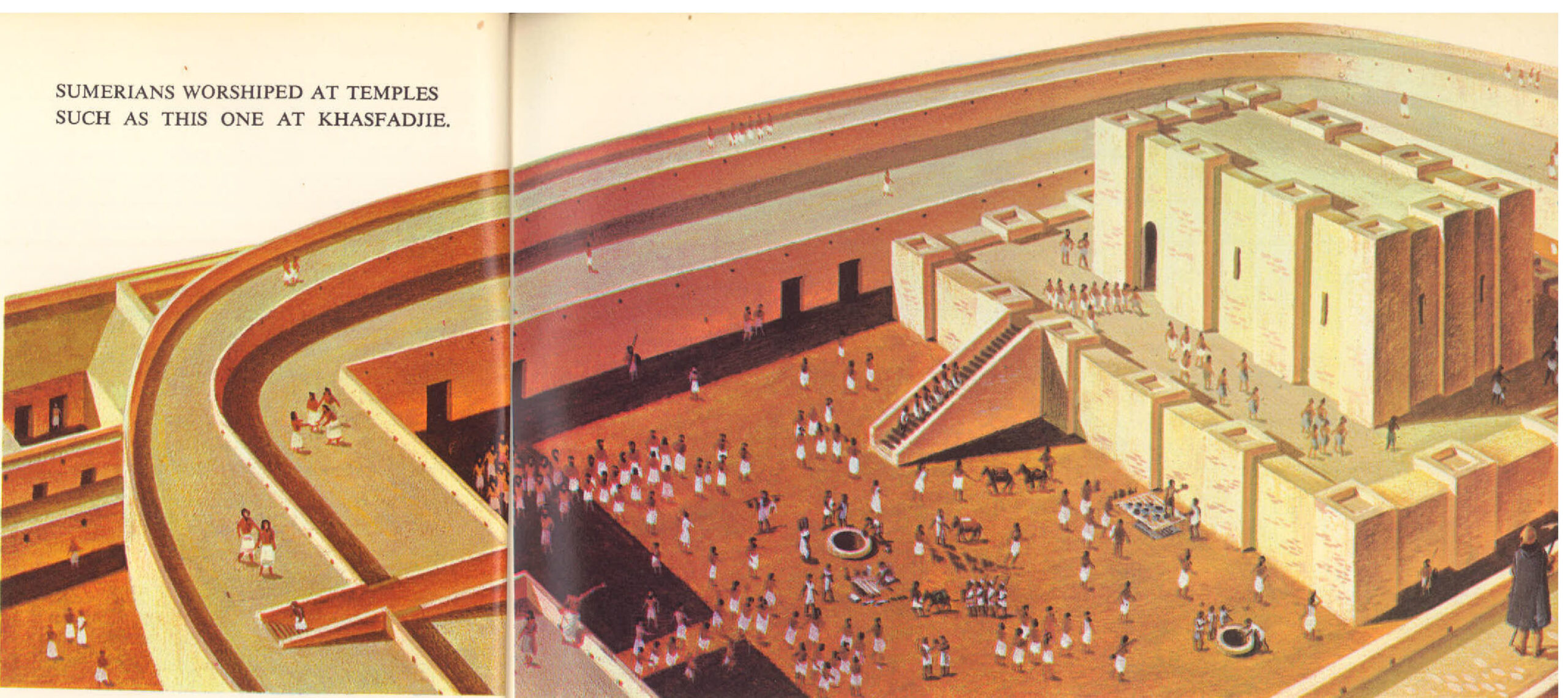

Mesopotamia, Where Civilization Began 4000 B.C. – 1750 B.C.

Mesopotamia is where civilization began. By 4000 B. C., many different groups of people were working out their lives in

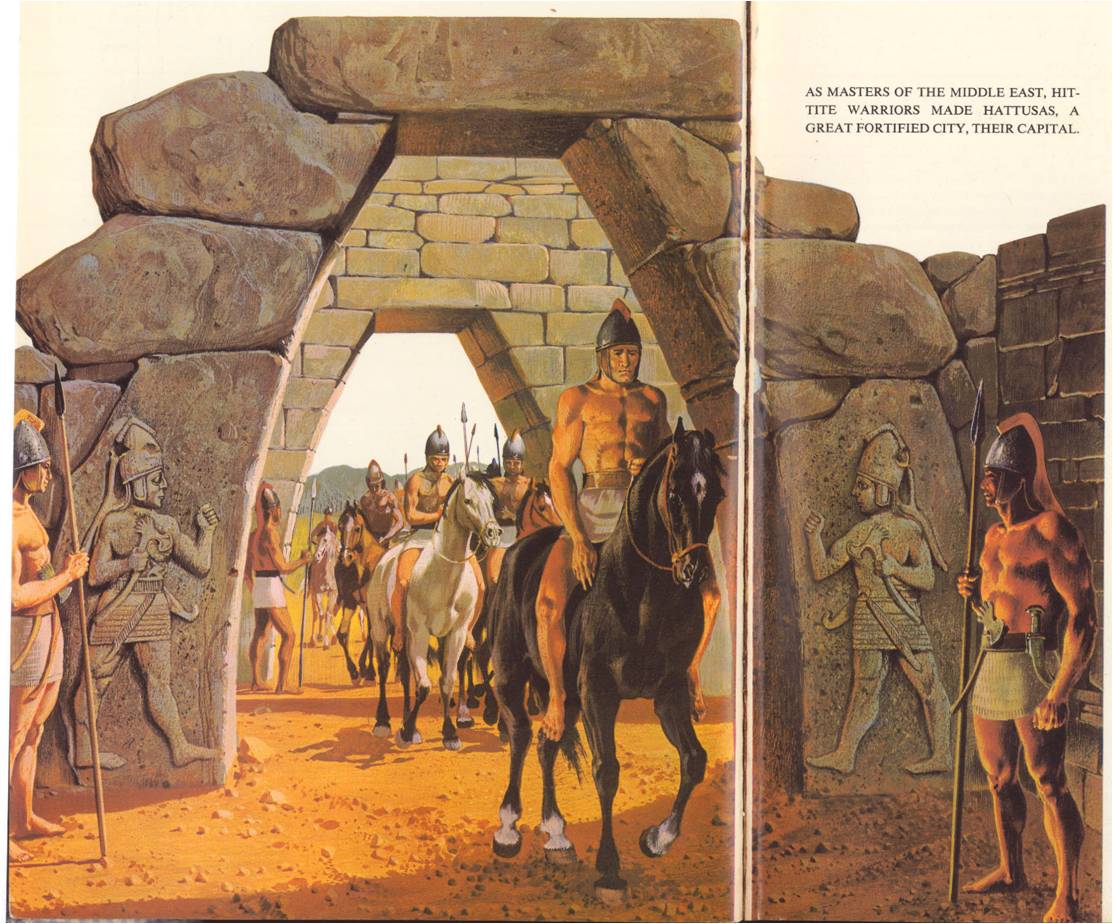

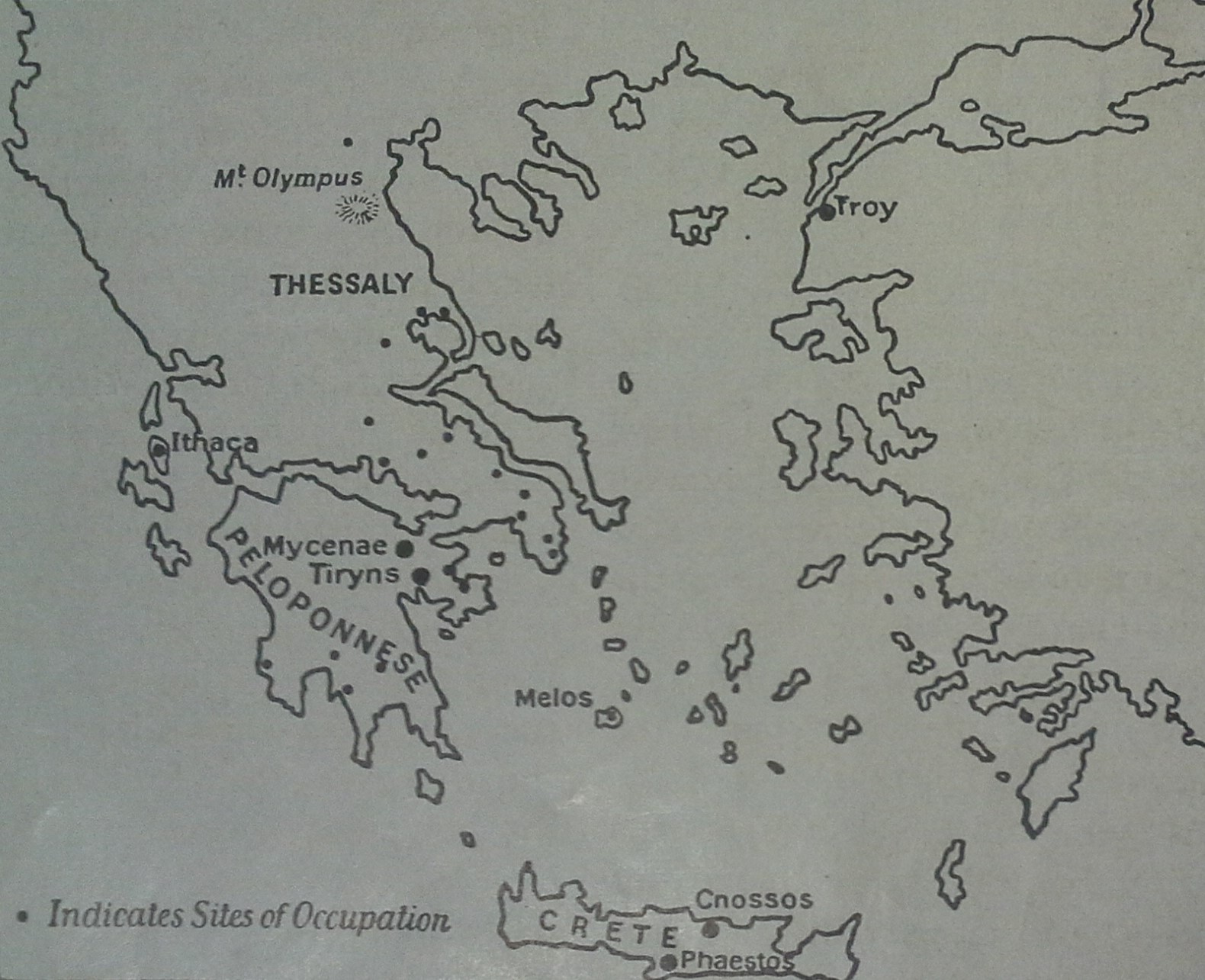

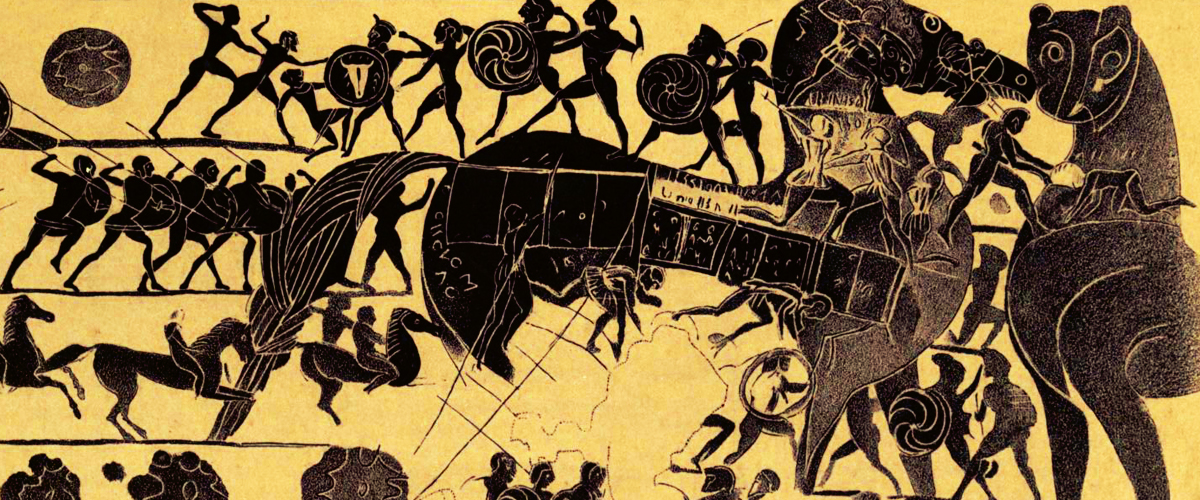

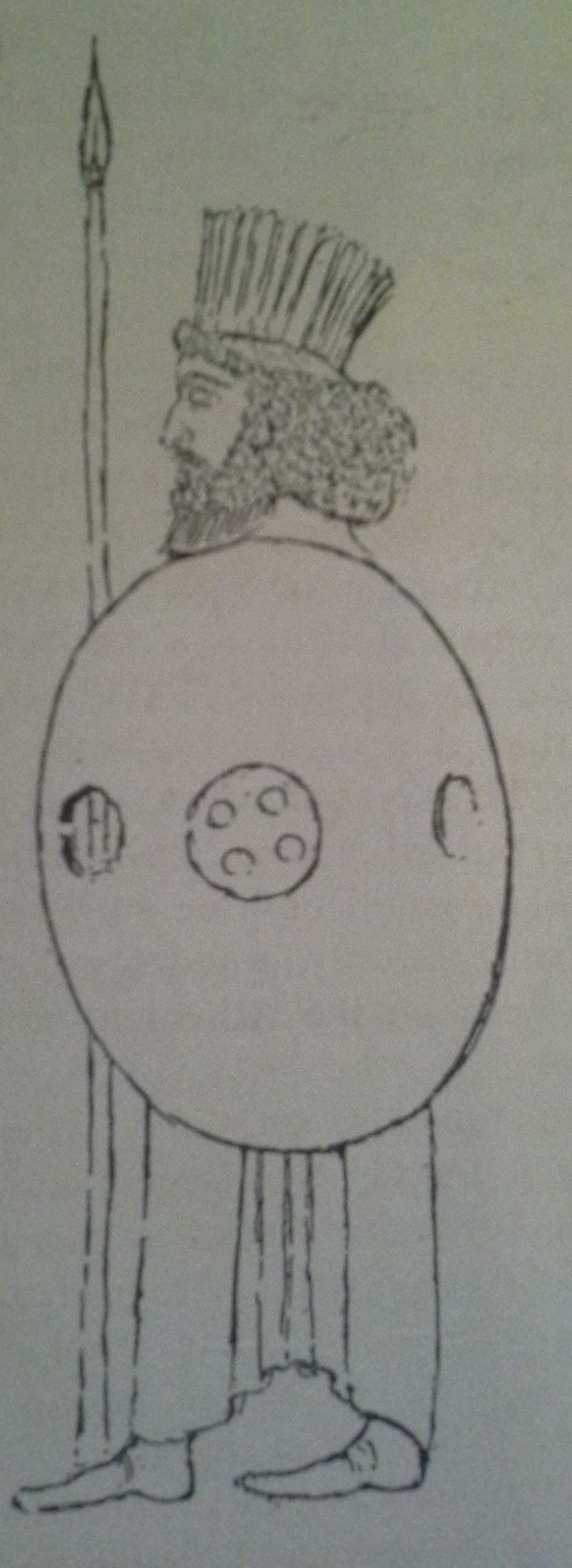

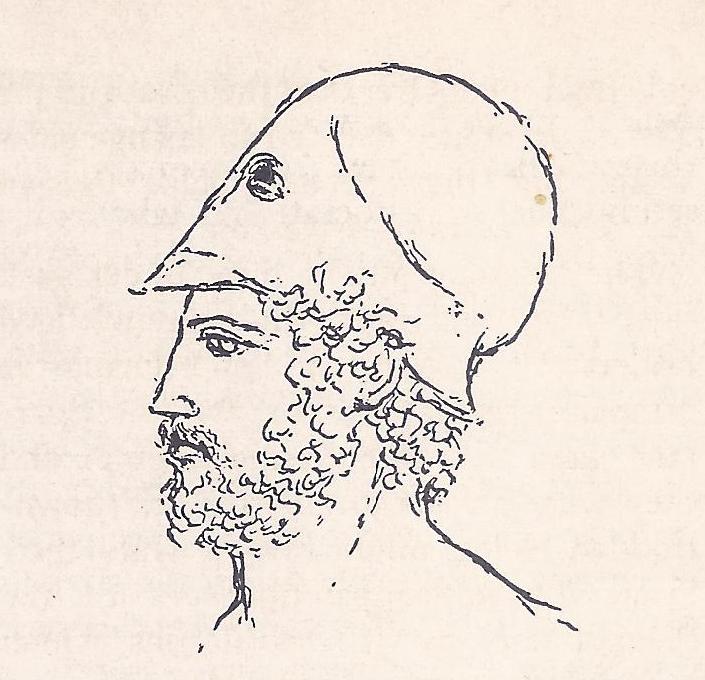

Hittite Warriors Build a Kingdom 1750 B. C. – 700 B. C.

Within 150 years of the death of Hammurabi, the cities of Mesopotamia were powerless and other peoples took up the

Distant Past and New Challenges

Milestones of History

What is History?

Many answers have been given to this question. To most people it is undoubtedly the record of past events, but

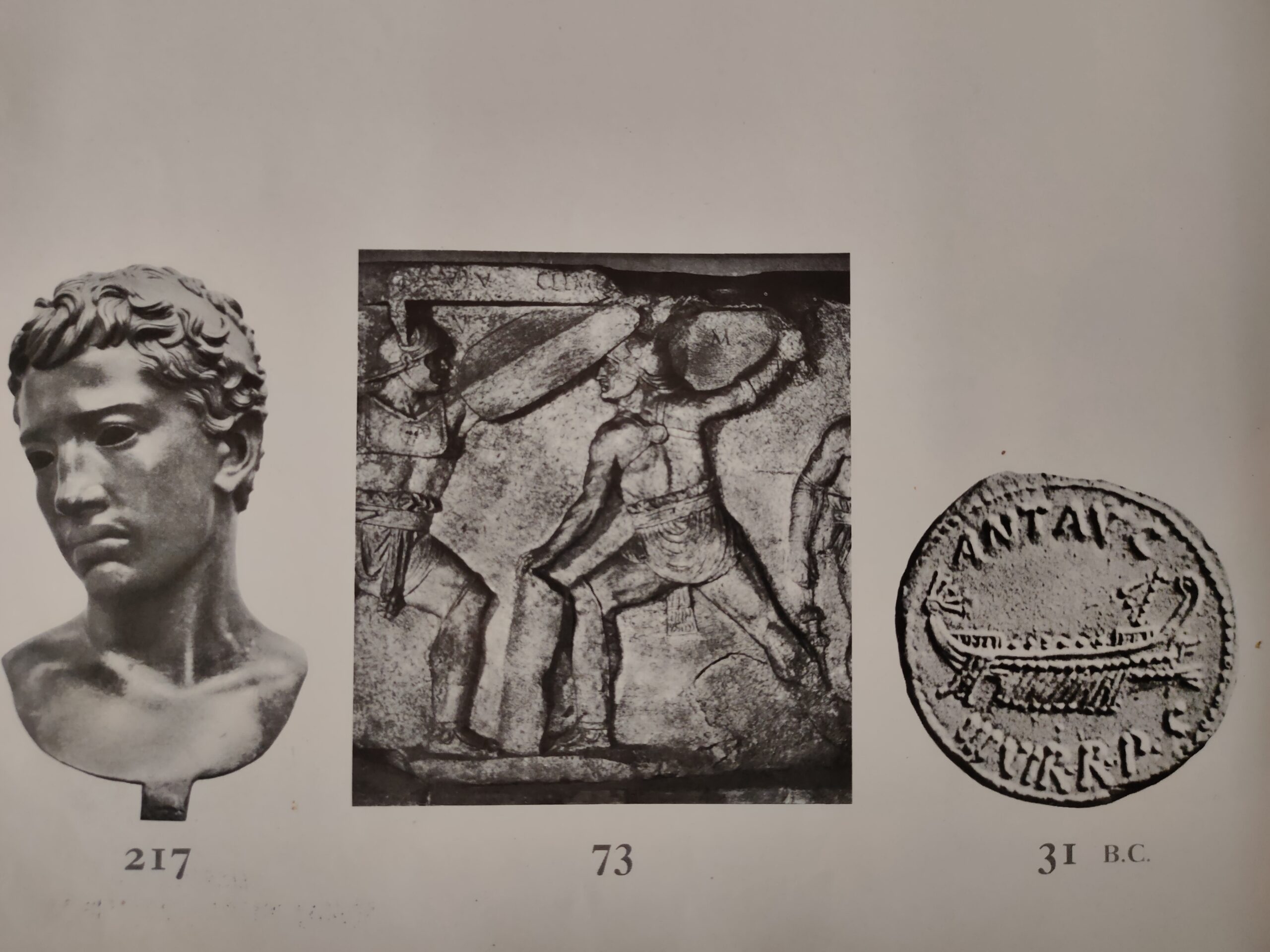

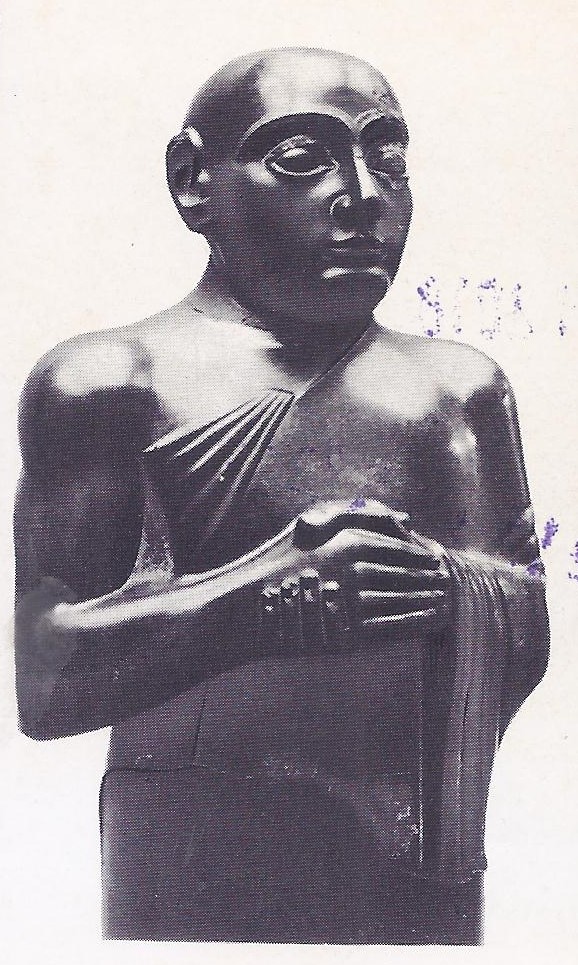

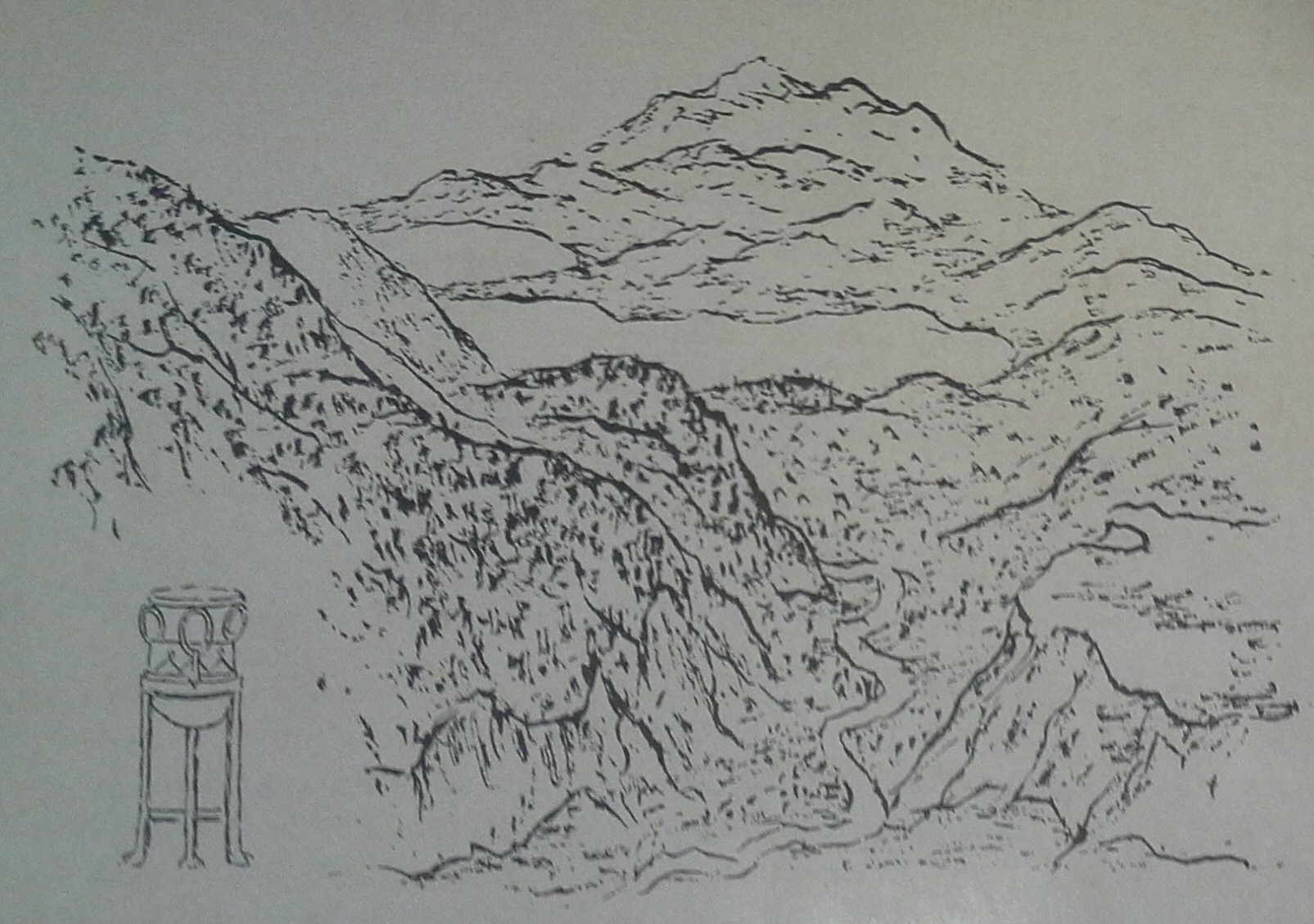

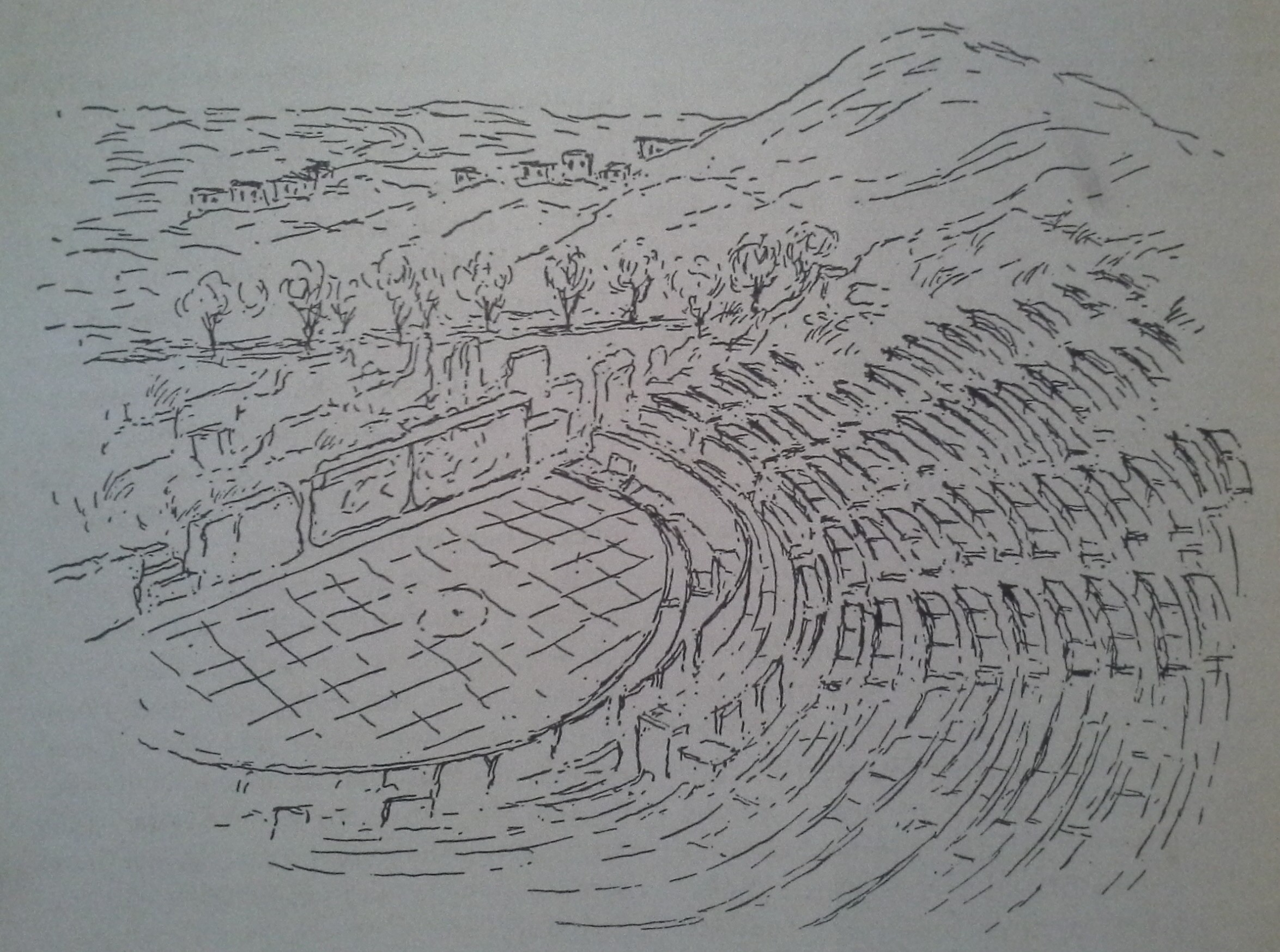

3000 BC – Gift of the Nile

On the long road to civilization, the emergence of the national state –particularly in the context of the world in

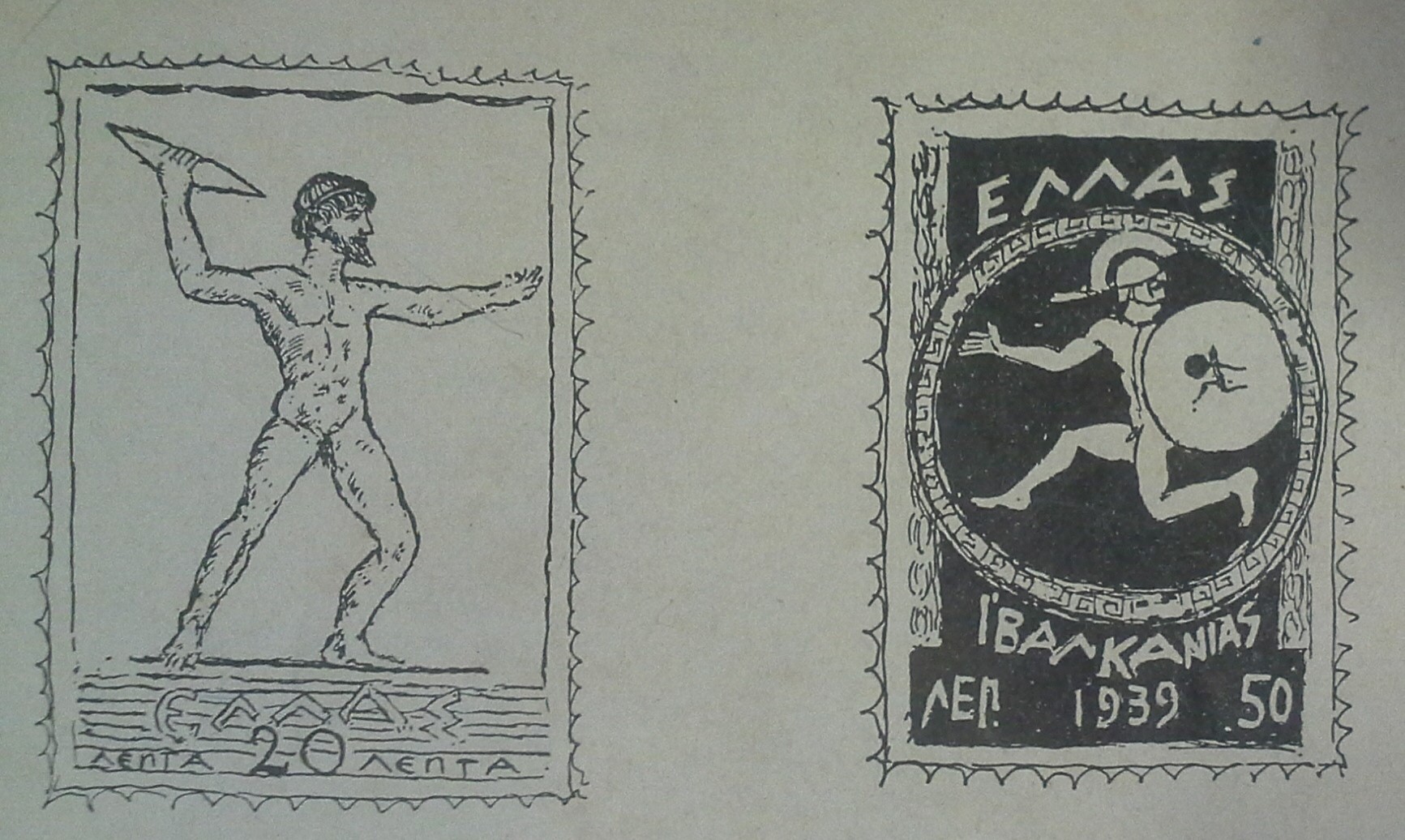

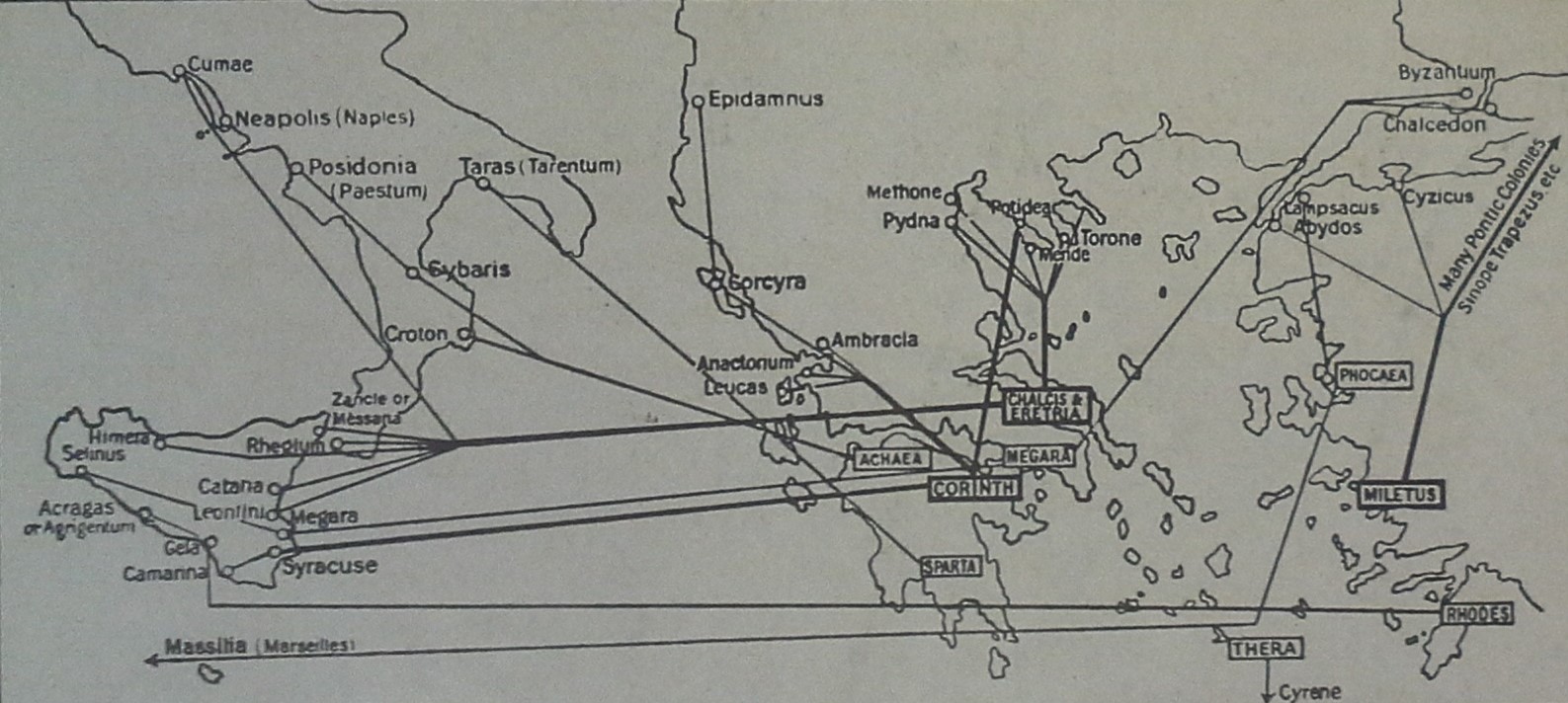

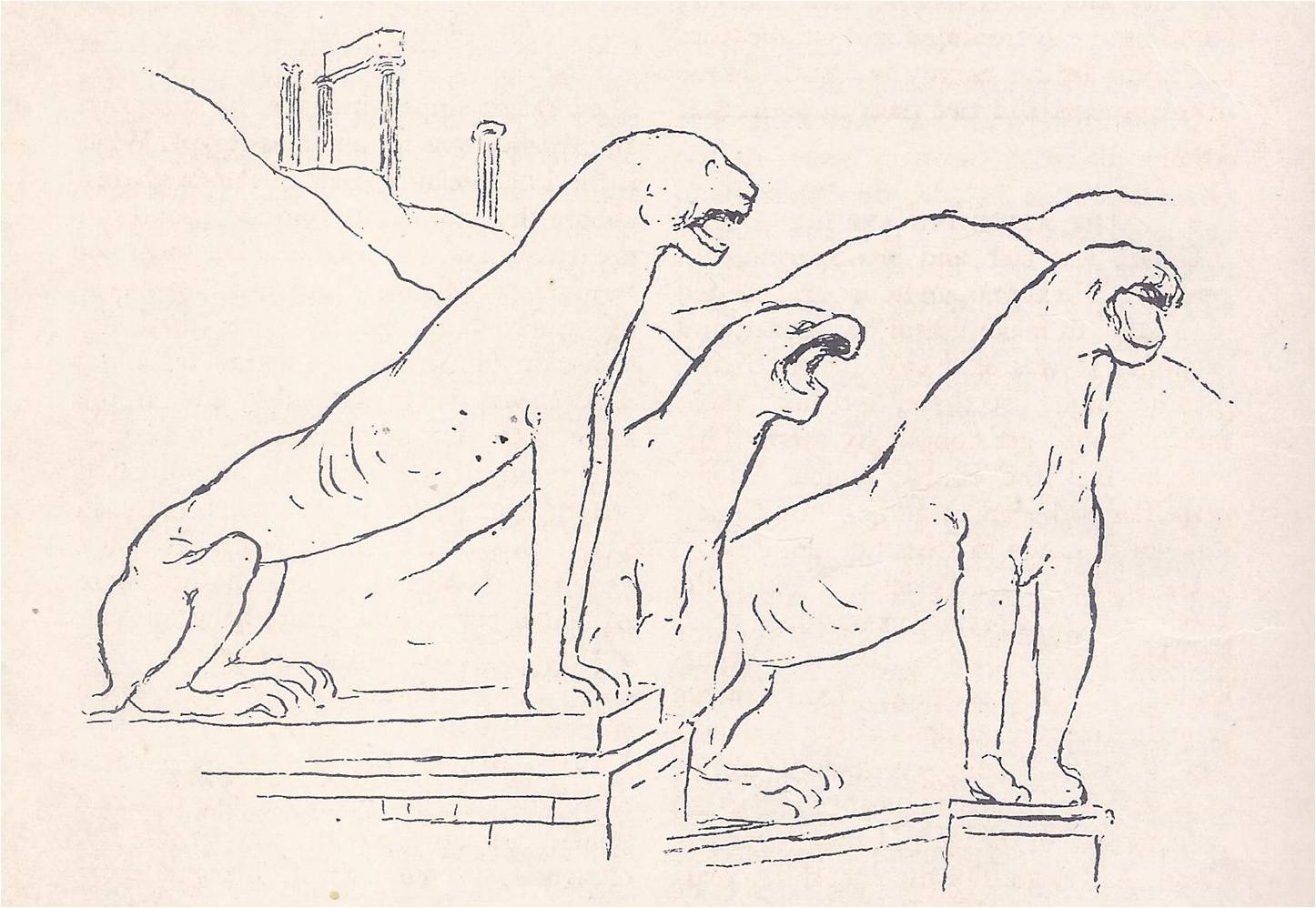

Early Culture Existed for Centuries

Early culture, between 3000 to 1750 BC, in Mesopotamia, the land between the rivers, another civilization is already far advanced.