IN THE spring of 1933, as the New Deal roared into action, business began to get better, but it dropped again and as 1933 ended and a new year began, even the most optimistic New Dealer had to admit that the depression was still on. During 1934, the government took further steps to regulate banking and finance‚ but some Americans were dissatisfied. Businessman complained that the government was making it harder to do business. In spite of all the excitement, the NRA was not working out well. The farmers were complaining that prices of farm products were still too low. Some farmers went on strike, refusing to take their crops to market. In the West, there was even violence as bands of farmers overturned trucks on highways to keep them from carrying farm products to the cities. Other farmers refused to let their neighbours’ farms be sold at auction. Surrounding the auctioneer, they would force him to sell the farm for a few cents and they would then give it back to its owner.

Nature itself was working against the farmers. A long drought was creating a great Dust Bowl in the states of the Great Plains — in Oklahoma, the Dakotas, parts of Kansas, Nebraska and Texas. As month after month went by with no rain, the wind stirred up dust storms that darkened the sky. The helpless farmers watched their soil blow away, leaving a wasteland where once there had been fertile acres. Thousands of families were forced to give up their farms. Packing their belongings into rattling, broken-down cars, they set out for California. There they looked for work picking fruit and vegetables in the vast fields. Called “Okies”–because so many of them came from Oklahoma — they became a problem in themselves. The owners of the California farms kept wages as low as possible and the Okies lived from hand to month. They moved with the harvest season, going wherever they could get a little work and whole families became ragged wanderers, always fearful of starvation.

Then, in May of 1935, something happened in Washington that shocked every New Dealer. The Supreme Court ruled that the NRA was unconstitutional and the proud Blue Eagle was a dead bird. What was shocking was not so much the fact that the NRA had been killed; after all, it had been a disappointment, but the Court’s decision made it appear as if no Federal law could be passed to regulate wages, hours, or other procedures in industry. Roosevelt called it “more important probably than any decision since the Dred Scott case.” He said that the big issue was: “Does this decision mean that the United States government has no control over any economic problem?”

Although this was a serious setback, the New Deal went on. Roosevelt kept experimenting and planning, changing his plans when necessary, doing what he thought best to beat the depression and bring reforms to the nation. In 1935 he set up the Works Progress Administration, or WPA. People on relief were given jobs and paid out of Federal money. They were put to work building and improving roads, bridges, parks, schools, hospitals, sewage and water systems. Professional people, including artists, actors and musicians, were also given jobs. Writers wrote reports, histories of various regions and guidebooks of the states. Artists painted pictures and did murals in post-offices and other public buildings. Musicians gave concerts and actors put on plays at low admission prices as part of the Federal Theater Project. To help young people between the ages of sixteen and twenty-five, the National Youth Administration was set up. It provided part-time work, so that students could continue to attend high schools and colleges.

That same year, Congress passed a bill increasing taxes on high incomes. It also passed the Public Utility Security Act, which regulated certain financial practices by electric power companies. Most important of all, it passed the Social Security Act, which would affect millions of Americans for years to come. Under this act, workers who retired at the age of sixty-five were to receive monthly payments for the rest of their lives. The amount would depend on how much they had earned during their working years. The money was to come from a special tax, half paid by workers, half by employers. The act also provided for pensions for the disabled and for the poor over the age of Sixty-five, for benefits to widows, children and for unemployment insurance, which allowed anyone who lost his job to collect benefits for about fifteen weeks.

When the Supreme Court outlawed the NRA, it had, of course, outlawed Section 7a, which gave workers the right to join unions without interference from employers. With the rise in union membership, labour had become more powerful in politics. Now labour leaders demanded something to take the place of Section 7a and on July 5, 1935, Congress passed the National Labour Relations Act. This act was often called the Wagner Act, after Senator Robert F. Wagner of New York, who led the battle to get it passed. Similar to Section 7a, it set up the National Labour Relations Board. The board was to supervise elections among workers in plants and industries so that they could be represented by the unions they wanted, or not represented at all.

Encouraged by the new law, thousands more workers joined unions. Yet, even as labour was growing in strength and power, it was divided. Most of the unions were part of the American Federation of Labour, or A.F. of L., which followed the policy of organizing workers in craft unions. There was one union for all carpenters, another for all bricklayers, another for all coal miners and so on. Some union leaders said this was an old-fashioned method. They wanted industrial unions — unions which would take in all workers in a particular industry, no matter what job they did.

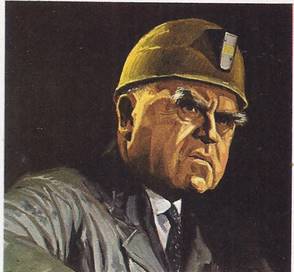

Among the supporters of industrial unions was bushy-browed John L. Lewis, head of the United Mine Workers. William L. Hutcheson, president of the Carpenters’ Union, disagreed with him and the two went at it with their fists at the A.F. of L. convention in 1935. That October, Lewis and the heads of seven other unions formed the Committee for Industrial Organization, which became known as the C.I.O., to work for industrial unions.

One of the unions allied with the C.I.O. was the United Automobile Workers and in December of 1956 it went on strike against Chrysler Motors and the mighty General Motors Corporation. The union tried something that had seldom been tried before in the United States — a “sitdown” strike. Instead of picketing, the workers stayed in the plants, so that strike breakers could not come in and do their jobs. Food was brought to them from kitchens set up by the union.

The sit-down was, technically, illegal and the companies were determined not to settle with the union. The strikers were just as determined. They were angry at the frequent lay-offs and the fast pace of the assembly line. It had not been easy for them to organize and they angrily accused the companies of spending large sums of money to hire detectives to spy on them and of finding some excuse to fire any man suspected of joining the union. So, the strikers sat it out, while the companies tried to get at them through the courts and the Federal and state governments tried to find a way to reach a peaceful settlement.

Whether the sit-down was or was not legal, the strikers had taken their stand and it was up to the companies to get them out. The police took a hand on January 11, 1937, when they rushed a plant in Flint, Michigan. They used tear gas and buckshot and the strikers fought back with pop bottles, pieces of pipe and anything else they could pick up. The strikers won the battle and the sit-down went on. Then the courts ordered them to get out and soldiers of the National Guard were to see that they did. The deadline was the afternoon of February 3, which was a freezing cold day. Thousands of union men gathered to stop the soldiers and there was danger of violence, but, before any fighting could break out, the men were cheering and dancing in the streets. News had come that General Motors was at last willing to meet with the union leaders. A week later, the company agreed to recognize the union and after 44 days, the strike was over.

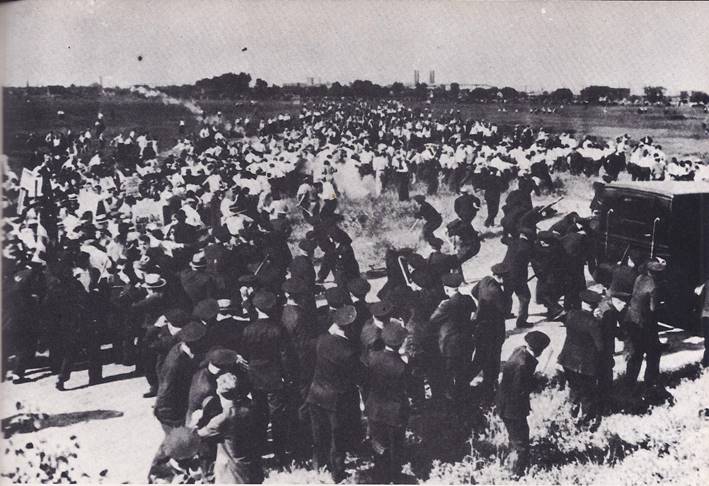

In March came an even greater surprise. The C.I.O. had been trying to organize the workers of the United States Steel Corporation, which labour had always considered one of the toughest foes. John L. Lewis of the C.I.O. had been quietly meeting with Myron C. Taylor, the steel company’s chairman of the board and they had worked out an agreement under which the company would sign a contract with the C.I.O. The United States Steel Corporation was “Big Steel,” the largest company in the industry. The smaller companies, known as “Little Steel,” refused to follow its lead and would not sign with the union until 1941. Meanwhile there were strikes and violence. On May 30, 1937, Memorial Day, ten workers were killed by the police at the Republic Steel plant in South Chicago, Illinois.

In spite of the difficulties with Little Steel, union membership kept rising. Weak and insignificant for so many years, unions became a familiar part of American life, but labour continued to be divided and became more so in 1938. The A.F. of L. suspended the unions in the C.I.O., which then became an independent group under the name of the Congress of Industrial Organizations.