Bells and trumpets sounded across Europe in the time that men would call the Middle Ages. Knights in glistening armour rode forth to serve God and their kings; life was like a stately procession winding through a landscape marked by castles and cathedrals. Each man knew his place. He was a prince, a knight, a squire, a priest, a craftsman, or a serf. He wore the clothes that belonged to his rank — the armour and family emblems of a nobleman, the robes of a churchman, or the rough wool jerkin of a serf. He lived according to an age-old set of rules — the knightly code of chivalry, the vows of a monk, or the duties of a serf to the lord who owned the land he farmed. Such, it was said, was the will of God.

It seemed impossible to imagine that life could ever be any different and indeed, almost no one remembered that it had been different in the past. In Athens, once the most beautiful and exciting city in the world, the palaces and temples of the Greeks were vacant ruins, overgrown with weeds. In Rome, the vast arenas and the Senate House were silent. The Forum, the ancient gathering place of Roman throngs and center of the greatest empire man had known was now a cow pasture. Hidden away in the castles and cathedral libraries, manuscripts that held the science, poetry and wisdom of two thousand years of life and discovery lay dusty and unread.

All this, too, it was said, was the will of God. To the men of the Middle Ages, ruins taught a lesson: life was short, the works of mankind soon fell to dust and a man’s time on earth should be spent only in preparing for death and what came after.

Yet, the stately procession of the Middle Ages did change. Towns grew up around the castles and churches. The townsmen turned to trade, grew rich, proud and refused to keep to their places. Scholars became interested in the past. They unearthed ancient manuscripts and journeyed to Rome to study the ruins and then they turned to Greece, whose artists and thinkers had led the way for the Romans.

“I go to awake the dead,” said one scholar as he set out for Athens. He could have added that he would return to wake the living, for the long forgotten knowledge of the past was bringing men face to face with the world about them. They opened their eyes and saw wonders on every side, and they saw themselves, the greatest wonders of all. Years later, historians talked of a dawning, the light of a new age that followed the Middle Ages. They called this new age the Renaissance — a French word meaning “rebirth” — because it seemed that the glories of Greece and Rome had been born again in Europe.

A TIME OF TURMOIL

Actually, the new age did not come as suddenly as a dawn. No one could point to a particular moment when the Middle Ages ended and the Renaissance began; the changes had begun far back in the age of chivalry and they did not happen in every place at the same time. By 1350, one peninsula of Europe – Italy — was alive with a new excitement which gradually spread across the continent, to France and Spain, to Germany, the Low Countries and Britain. As late as 1500, a Netherlander talked of a “dawning,” and in 1600, when Italy had lost its spirit of adventure, the Renaissance was at its height in Queen Elizabeth’s England.

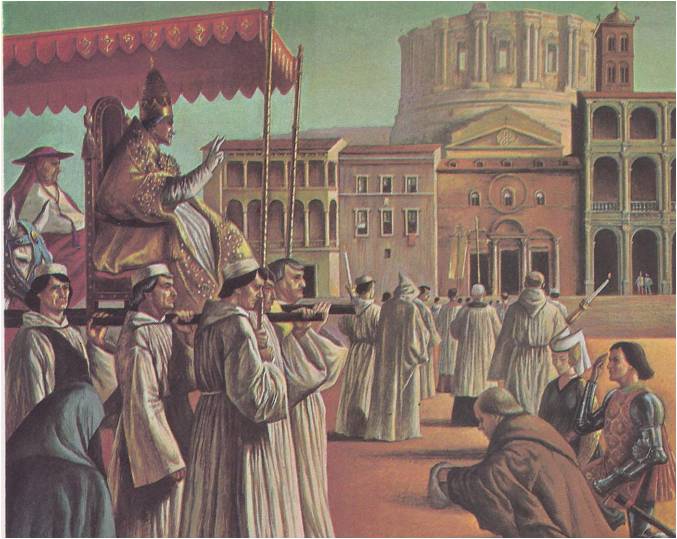

One thing, however, was certain. Everywhere, the time of awakening followed a nightmare of violence and suffering. Italy in 1300 was a mammoth battleground where the new merchants and old lords fought for the control of towns and the two greatest rulers of Europe contended for power. The nobles sought the aid of their master, the chief commander of the knights, the Holy Roman Emperor‚ whose empire stretched from Germany across much of Europe and included all of Italy. The merchants, in turn, called for the help of the pope, the leader of the Church, whose capital was Rome and whose realm was Christendom — all the cities and states whose people belonged to the Catholic church, the one Christian church in Europe. The pope and the emperor, “the ruler of men’s souls” and “the ruler of men’s bodies,” were old rivals. The two rulers had usually been content to argue and to threaten one another. When the emperor threatened to use his armies of knights, the pope answered that he would see to it that none of those knights was admitted to heaven and nothing more was done. In Italy the old quarrel flared into war.

Italy was divided into many feuding city-states and every city-state was divided between the supporters of the emperor and the supporters of the pope, the Ghibellines and the Guelphs. The two groups showed their enmity in everything they did. Each had its own special way of wearing a cloak, shaping a battlement, or pronouncing certain words. Ghibellines wore white roses, Guelphs wore red. Ghibellines sliced their fruit in one way, Guelphs in another, but they were not so particular about the way they sliced each other with their swords. Rome, the pope’s city, was also the stronghold of fierce clans of noblemen. Their bloody feuds made life in the city so dangerous that in 1305 the pope was forced to flee to Avignon in France. For nearly a century, the papal court remained at Avignon, while Rome grew poor, its people lived in fear and its streets and vacant mansions echoed with the shouts of war and terror.

Meanwhile, the emperor struggled with rebellious lords who threatened to rob him of his German lands. He had no knights to help noblemen of Italy. One by one, the Italian city-states claimed their independence– and, independent, went on fighting among themselves more fiercely than ever.

THE DANCE OF DEATH

Then came the plague, the “Black Death.” It marched through Italy and across Europe, slaughtering men by the tens of thousands. Houses and shops were abandoned, the dying were left untended in the streets: The dead were buried hundreds at a time in huge trenches, because there were not enough diggers to make graves or enough priests to give funerals for so many. The wars stopped, but so did trading and farming and many who escaped the plague died of poverty and famine.

The stately procession of life became the Dance of Death, a favourite subject for church painters: a terrible parade of knights and lords and peasants headed by a skeleton who led them to their doom. Some men locked themselves in their houses and prayed, some tried to forget their fears by drinking and making merry, and hopelessly they waited to die.

In the little towns of Italy, there were men who did not give up so easily. The merchants, who had braved the anger of the lords, struggled to live and to save their businesses. The traders and shopkeepers and craftsmen had already organized guilds, which set the schedules and wages of workers and controlled the prices and quality of goods. Now the guilds kept order in their towns and searched for trade wherever they could find it. When the plague had ended, the guilds sent their salesmen to the old markets along the northern trade routes. Italy grew prosperous as the Italian traders became the merchants and bankers for all of Europe. Their new fortunes gave the guildsmen power. All but the most stubborn noblemen were forced to come to terms with them and indeed, in many towns the lords and merchants combined forces and ruled together.

The guildsmen were still not satisfied, however, for they meant to be as great as the noblemen in every way. They began to buy the luxuries that once only the lords had been able to afford. They built palaces, bought the work of the finest painters, goldsmiths, tapestry weavers and hired tutors to teach them the things that gentlemen should know. They gave a particular welcome to the new scholars who taught the Greek and Roman belief that a man was not born noble but became noble.

Among these scholars was Francesco Petrarch, who would one day be called the first man of the Renaissance. Angry with the dull professors and duller books that had given him “seven wasted years” at college, Petrarch had set out to educate himself and had discovered the Romans and the Greeks. Journeying from town to town in Italy, he proclaimed the beauty of the ruins at Rome and stirred up a treasure hunt for old manuscripts. The wisdom in these books, he told the merchants, was “more valuable merchandise than the rarest goods of China and Arabia.” The merchants listened, for Petrarch was the most famous poet in Europe, the friend of kings and popes and the first of the men of learning who said that a man’s nobility depended, not on birth, but on what he did.

Before his death, in 1374, Francesco Petrarch had become first in a number of fields. He was “the first tourist,” who dumfounded his friends by climbing a mountain merely to see the view. He was the first of the Humanists, the Renaissance philosophers who opened their eyes to view the wonders of the world and men. Their philosophy was called humanism because it began with the study of mankind instead of the mysteries of God. Petrarch called it half science and half love.

Greatness, more than love or science, was the goal of the ambitious Italians who made the Renaissance. Men competed for position and wealth, cities for land and power and men and cities alike, proved their greatness with displays of splendor. Merchants spent their profits on palaces, churches, paintings, statues, manuscripts and sumptuous feasts. The merchant-rulers of Florence set out to show Italy that a city of commoners could be as splendid as any city ruled by noblemen. With the help of the Medici family, the richest bankers in Europe, they succeeded and Florence became Italy’s capital of art and learning, the first city of the Renaissance.

THE NEW ARTISTS

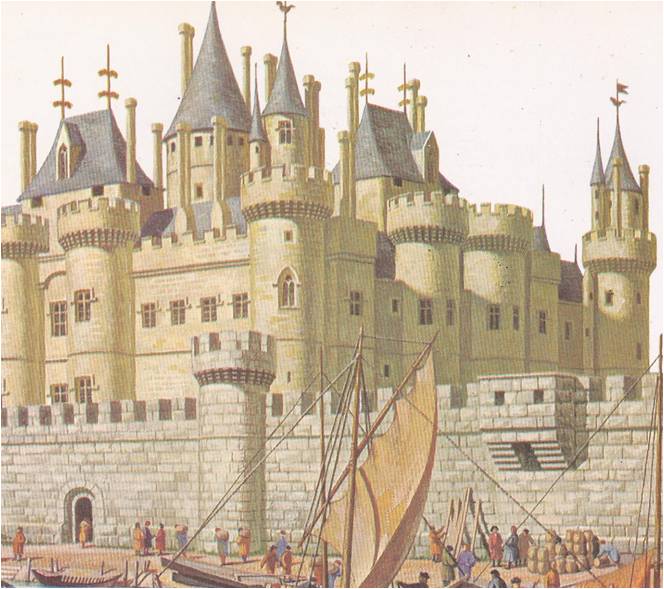

The rulers of other Italian city-states hurried to catch up with the Florentines. In Milan and Pavia and Ferrara, dukes built castles and cathedrals, libraries and pleasure palaces rose. The merchants of Venice filled their island city with palaces. Rome began to regain its old glory when the pope returned from France and his churchmen developed a surprising enthusiasm for earthly splendour. The pope had lost much of his power during the years that he was at odds with the emperor. His church had been divided by quarrels and for a time there had been three rival popes, each claiming that he was the one true leader of the church. When the arguments were finally settled and once again one pope led all the church, he had to make a display of his wealth and strength. The call went out from Rome for architects and painters and sculptors who could decorate the city in a manner befitting the monarch of Christendom.

The artists who served the pope, the merchants and the nobles during the Renaissance were very different from the nameless craftsmen who had worked on the old cathedrals. The names of the new artists were well-known and many rulers and cities competed for their services. They were welcomed as honored guests in the courts of kings and in their home towns they were treated as heroes. Art was a matter of everyday importance. A town that could claim no leading painter or sculptor as its own was embarrassed, while one that had many famous artists boasted of its good fortune.

Artists were kept so busy that many maintained workshops –almost factories — where brothers, cousins, sons and a squad of apprentices worked on dozens of projects at a time. There were more than paintings and statues to do, for an artist was also expected to design and carve furniture, paint festival cloaks and carnival masks, mold candlesticks and chandeliers, plan scenery for plays, make jewelry and decorate the cakes served up on the birthdays of dukes and wealthy merchants.

Scholars, like artists, were also in great demand. Men of learning were considered a necessary adornment for any court and education was the mark of a gentleman. The humanist teachers did their work well. Their best students became the models of intelligence and courtly behavior for all of Europe. When the invention of movable type made it possible to print books by the thousands instead of hand-copying them one by one, the scholars did a masterly job of editing the ancient writings. The humanists’ eyes were almost always on the past and too often they wasted their energy in furious battles over odd bits of ancient grammar. With all their polished Greek and perfectly phrased Latin, they never matched the poetry of Petrarch or the lively tales of his friend Boccaccio, who wrote in the living language that the Italians spoke every day. The new humanist philosophy, though noble and humane, was confusing. The humanists tried to combine the beliefs of the Greeks with the religion of Christianity and the result was something of a muddle.

Of course, the Renaissance itself was a muddle — of beauty and ugliness, wisdom and greed, culture and cruelty. It was an age in love with color and finery, silks and damask, jewels and dishes of gold, pageants, feasts and masquerades. At the same time, it was an age of violence and vicious battles for power. Ambitious men often settled their differences with daggers, swords or poison. Great patrons of art and learning were also great tyrants, the Renaissance princes who lived for power and looked on murder or the destruction of cities as a simple matter of state business. In the Renaissance, diplomacy, too, became an art — the sly art of winning friends among rulers and states by charm and bribes, promises and threats. Peace was rare and the rulers who competed for artists and scholars competed as well for the services of the condottieri, generals who fought for pay.

PROFESSIONAL WARRIORS

Powerful and proud, the condottieri roamed Italy with troops of tough professional soldiers, offering themselves for hire. War was no longer a matter for unskilled armies of farmers and shopkeepers and the largest city-states — Florence, Milan, Venice and Naples — grew because they could afford to hire the best professional warriors. Some of the condottieri were men of rank, the rulers of small dukedoms, who supported their courts and people by fighting wars for princes of larger, richer cities. Some were commoners or peasants, who gambled their lives to win gold, fame and perhaps a city of their own. Some became heroes, honored and rewarded by the rulers they served; some won evil fame for their cruelty and greed; some stole their masters’ cities; but none lacked employers.

The Middle Ages had been a time of waiting and caution. The Renaissance was an age of action, adventure and daring. “It is granted to man,” wrote the humanist Pico della Mirandola, “to have whatever he chooses, to be whatever he wills.” That was the true philosophy of the Renaissance men, who fought wars and read Greek, wrote poetry and music, loved beauty in paintings and women and strove to be excellent in everything. It was also the belief of the merchants and nobles who vied for honor and magnificence, of artists who competed to create the most splendid statues and paintings and of explorers who braved unknown oceans in search of new lands.

Besides the great men, there were thousands of lesser men. They were the poor who did the work, who farmed and built and fought battles. They rejoiced at the victories and suffered in the defeats and tried to go on living. For them, too, life was a gamble and as before, they looked to the leadership of the princes and the church.

The bells and trumpets still sounded across the land, but in the first great cities of the Renaissance — in Florence, Milan, Venice and Rome — and later in the awakening cities of France, the Lowlands, Spain and England, life was no longer a stately dance. It had become a contest of ambitious men anxious for greatness, riches, power and fame.