The big English setter did not look like a stray dag. When it came wandering into Washington’s camp one day in the fall of 1777, a soldier brought it to his officer. The officer took it directly to Washington’s headquarters and pointed out the name on the dog’s collar–“General Howe.” Washington had the dog fed while he wrote a polite note to General Howe. Half an hour later, the dog and the note were sent to the British camp under a flag of truce.

The incident was not important, but it gave the Americans something to laugh and joke about for several days. There had not been much cause for laughter in recent weeks. General Howe had taken Philadelphia, America’s capital and its largest city, after defeating Washington at Brandywine and at Germantown. Washington’s losses had been heavy. He was now camped in the hills of Valley Forge, some twenty miles from Philadelphia, in desperate need of supplies of all kinds.

In the North, moving down from Montreal, General Burgoyne had captured the fort at Ticonderoga and had continued on to Fort Edwards on the Hudson. Burgoyne, however, was having his troubles, too. He was almost out of food and his supply base at Montreal lay 185 miles north, through almost trackless wilderness.

Burgoyne knew that east of him there were large stores of food and many cattle at Bennington, in what is now Vermont. He sent out a detachment of 1,300 men to raid the place and to bring back all the cattle and horses they could find. The detachment marched into a trap which had been set for it by John Stark and his New England militia and when the short battle was over, the British had lost. American losses were thirty killed and forty wounded. The Indians with Burgoyne lost faith in his leadership and deserted him. He now had no choice but to wait in the wilderness for supplies from Montreal and that meant a delay of at least a month.

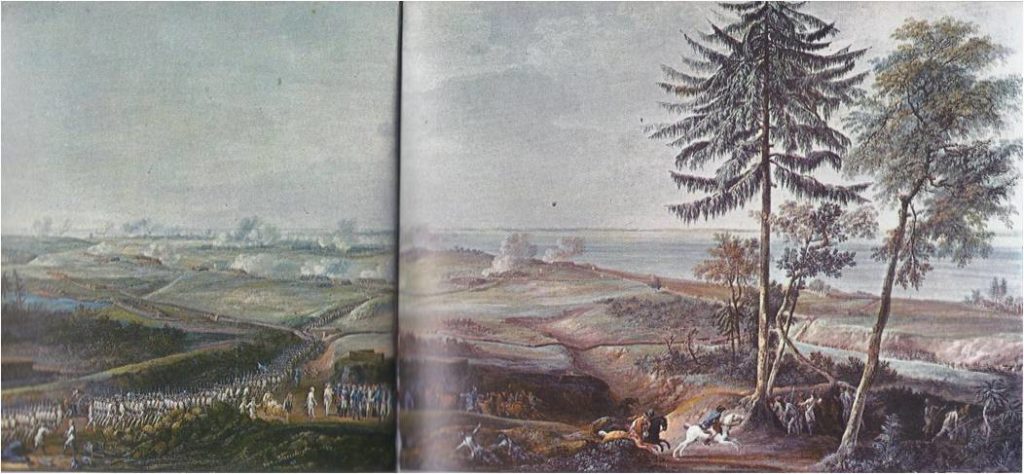

The delay gave an American army under General Gates time to establish itself in the upper valley of the Hudson. Gates’ army grew rapidly as he waited, for the American victory at Bennington prompted thousands of patriots to join his forces. When the British and Americans finally met at Freeman’s farm, the British were driven back. They retreated toward Saratoga‚ but Burgoyne soon found himself surrounded by Americans. On October 17, 1777, he surrendered, giving up his ivory-hilted sword to Gates.

FRANCE ENTERS THE WAR

Burgoyne’s defeat at Saratoga was the turning point of the war. Some five thousand redcoats, nearly a fourth of the British troops in America, were taken prisoner. News of the American victory was enough to bring France into the war on the side of the Americans, and later, Spain and Holland also declared war on England. The kings of these three countries did not join the fight in order to support the American rebellion. In fact, they were uneasy about it. They did not believe in freedom for the individual and were very much against the idea that the common man was fit to govern himself, but all of them hated and feared England and they felt that their best chance to defeat her was to strike while she was having difficulties with her American colonies.

France sent her navy to threaten the British supply lines across the Atlantic. She also loaned the Americans money and sent large shipments of clothing, war supplies and food. Many months were to pass, however, before any of these supplies reached General Washington. Meanwhile, shortages of food, clothing and shoes caused extreme hardship at Valley Forge that winter. Almost 4,000 troops were reported unfit for duty and 5,000 deserted. Washington begged Congress for help. “Few men have more than one shirt and some none at all,” he wrote. “Men in camp are unfit for duty because they are barefoot and otherwise naked. For want of blankets, numbers are obliged to sit up all night by the fires instead of taking comfortable rest in a natural way.”

It was at Valley Forge that two outstanding foreigners joined Washington’s army. One was a young nobleman from France the Marquis de Lafayette. He became a close friend of Washington and used his influence to get more active support from the French. The other was a German military man, Baron von Steuben. He trained Washington’s troops and young officers and built the American army into a more effective fighting machine than it had ever been before.

In Philadelphia, General Henry Clinton replaced Howe as commander of the British forces in America. He gave up Philadelphia, marched his army back to New York and soon launched a new campaign in the southern states. There were many loyalists in the South and he counted upon their strong support. General Clinton believed he could win the war by taking possession of the country, section by section, starting in the South and working north.

The southern campaign began with the capture of Savannah, Georgia, in December, 1778. By the following summer the British were occupying large areas in Georgia and South Carolina. They cornered an American army under General Benjamin Lincoln at Charleston and forced him to surrender his army and the city in May of 1780. Five thousand American troops were taken prisoner, in the most serious American defeat of the war. Three months later the Americans lost another battle and two thousand troops when Cornwallis defeated General Gates at Camden.

During all this time, Washington’s army remained near the Hudson to serve as a constant threat against Clinton’s army in New York. Lafayette had been in Paris for over a year. He returned to Washington’s camp with wonderful news. He had persuaded the French to send 6,000 of their best troops to America under the command of General Rochambeau and they were already at sea.

A TRAP FOR CORNWALLIS

Washington placed General Nathanael Greene in charge of the American forces in the South. Greene lost a number of battles, but he slowly wore out the enemy with his long marches and surprise attacks. For Clinton’s plan for conquering the South by sections had one great weakness: he did not have enough troops to defend the areas he had already won. Most of his regulars were needed as combat troops by Cornwallis, who commanded British forces in the South. Cornwallis failed to get as much support from southern loyalists as he had expected and those who joined his army could rarely be depended upon when they were most needed. The British did leave small units of regulars and loyalists behind to guard various strong points they had taken, but Greene, with the help of armed bands of patriots, struck at these strong points and forced the British to withdraw from a number of them.

By this time, Cornwallis had lost faith in the southern loyalists and in Clinton’s plan for taking the South. Having failed to destroy Greene’s army, Cornwallis marched northward into Virginia. There, for a time, he carried on a cat-and-mouse campaign against a small American army under Lafayette, trying to force the Americans into battle. When this attempt failed, Cornwallis withdrew to Yorktown on the coast, at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay and began to fortify it.

In the middle states, Washington was still a threat to Clinton’s army in New York, but three years of waiting for action had made Washington’s troops restless. Keeping trained regulars in the army had become more difficult than ever, for Congress was paying the soldiers with paper money that was almost worthless. Washington complained, “A wagon-load of money will scarcely buy a wagon-load of provisions.”

Washington was also unhappy about the French army commanded by General Rochambeau. It had landed at Newport, Rhode Island, a year ago and had been there waiting ever since. The French had refused to join in an attack on New York. The city was too well fortified to be taken by land forces alone, Rochambeau believed. Washington had finally written to Admiral de Grasse, commander of a large French fleet then in the West Indies, explaining the problem and asking him to come north and help attack New York.

On August 14, 1781, Washington received his answer. De Grasse regretted he could not go north as far as New York; he had to return to the West Indies in the fall. he was sailing his fleet north to Chesapeake Bay in the hope that he might be useful there. He was bringing with him 3,000 troops and some cannon.

At once Washington changed his plans. Yorktown was located on a narrow strip of land with wide rivers on each side and the ocean at one end. With the French fleet in Chesapeake Bay, he could close in on Cornwallis from land and sea. Lafayette and his small American army were already in the area.

To keep the British in New York guessing, Washington ordered his men to begin building fortifications on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River, just opposite New York. He also spread the rumor that a big attack on New York was about to be launched. One morning late in August, General Clinton learned from his spies that the Americans were gone. Their large encampment across the river was vacant. Later, he learned that Washington’s army and the French army of Rochambeau were marching southward through New Jersey.

Cornwallis, meanwhile, was still building his fortifications at Yorktown. He had so much faith in the British navy that he did not regard the Yorktown peninsula as a dangerous trap. The ocean at his back was like a friendly doorway through which he could receive aid and supplies from the British fleet. If he were to be attacked by a large enemy force, his fortifications could hold out long enough for him to get reinforcements by sea. If the enemy became too strong, he could ask the navy to take him off the peninsula, thus allowing him to strike at some other place along the coast.

THE BATTLE OF YORKTOWN

Washington, too, had respect for the British navy. He did not know where it was, but he realized that it could prevent him from gaining a victory over Cornwallis. Then, shortly after the Americans had passed through Philadelphia on the long march to Virginia, a rider came galloping up from the south with a letter from Admiral de Grasse. The French fleet had arrived at Chesapeake Bay, landing 3,000 troops on James Island. Washington was so filled with joy that for once he forgot his dignity. He became so excited that he ran to Rochambeau, waving his hat in the air as he shouted the wonderful news.

Victory seemed certain — provided the British navy did not arrive to upset his plans. Now speed was important; every day was precious. The two armies quickened their pace. They marched through Baltimore and a day later they crossed the Potomac River and entered Virginia. When they reached Williamsburg, Washington was again greeted with cheerful news. Admiral de Grasse had spotted the British fleet at sea, had sailed out to meet it and had defeated it in battle. The French fleet was now in complete control of the sea. Cornwallis was hopelessly surrounded.

Washington brought up his cannon and began the mightiest artillery attack of the war. The big guns boomed day after day. Cornwallis was forced to withdraw from his outer defenses. The French and Americans moved in closer and hammered away at Yorktown itself with two hundred cannon. By October 14, they were storming the British redoubts and a counterattack two days later failed to push them back.

Finally, at ten o’clock on Wednesday morning, October 17, a drummer boy in a red coat climbed to the top of a British breastwork and began beating his drum. The sound of his drumming could not be heard above the constant thunder of cannon fire and clouds of swirling smoke made him almost impossible to see. Then, in a moment when the smoke cleared a little, someone spotted him.

Orders were passed to the gunners and the big guns stopped firing. A British officer appeared on the breastwork beside the drummer and waved a white handkerchief. As he came forward, an American officer ran out to meet him, blindfolded him and led him back behind the lines. The Englishman carried a letter from Cornwallis asking for a twenty-four-hour truce to arrange for the terms of surrender. Slowly the dust and smoke of battle drifted away, revealing the clear blue of the autumn sky. The American and French soldiers, a little timid at first, came out of their trenches and looked around, as if puzzled by the uneasy stillness. Before long, many of them stretched out on the ground and fell fast asleep in full view of the British.

WORLD TURNED UPSIDE DOWN

On the afternoon of October 19, 1781 the French and American armies marched out in a field beyond Yorktown and formed two long lines facing each other. A column of British soldiers, 7,000 in all, filed slowly out of Yorktown and passed between the two lines, their drums and fifes playing an English tune called “The World Turned Upside Down.” At the end of the field the British stacked their guns, laid down their drums and colours and returned to Yorktown to await further orders as prisoners of war. With the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown, the war all but came to an end. For a time Greene continued his campaign in the South. Late in 1782, the British withdrew from Charleston and Savannah and held only one city in the entire country-New York. Peace came at last with the signing of the Treaty of Paris on January 20, 1783. England recognized the independence of the United States of America, giving the new nation all territory north to Canada, west to the Mississippi and south to Florida.

The American victory over the strongest colonial power in the world prompted other colonies to think about independence, too. In South America for example, local leaders tried to stir up the people by pointing out the unfair way they were being treated by their Spanish rulers. The American Revolution also influenced the people of Europe. They had watched it from beginning to end, feeling that it was not so much a war for independence as it was a revolt of a people against their king. They themselves had lived and suffered under royal rulers for many centuries and to them the war meant a fight for the rights and freedom of ordinary people and the success of the revolution, a great victory for the common man.

The United States joined the family of nations as an equal and began a bold experiment with a new form of government, a republic, one in which the people ruled over themselves through their chosen representatives. Whether a republic could succeed or not was a question no one could answer. The fact that the American people had been able to set up their own form of government gave ordinary people – the world over – new hope and planted the seeds of rebellion in many lands.