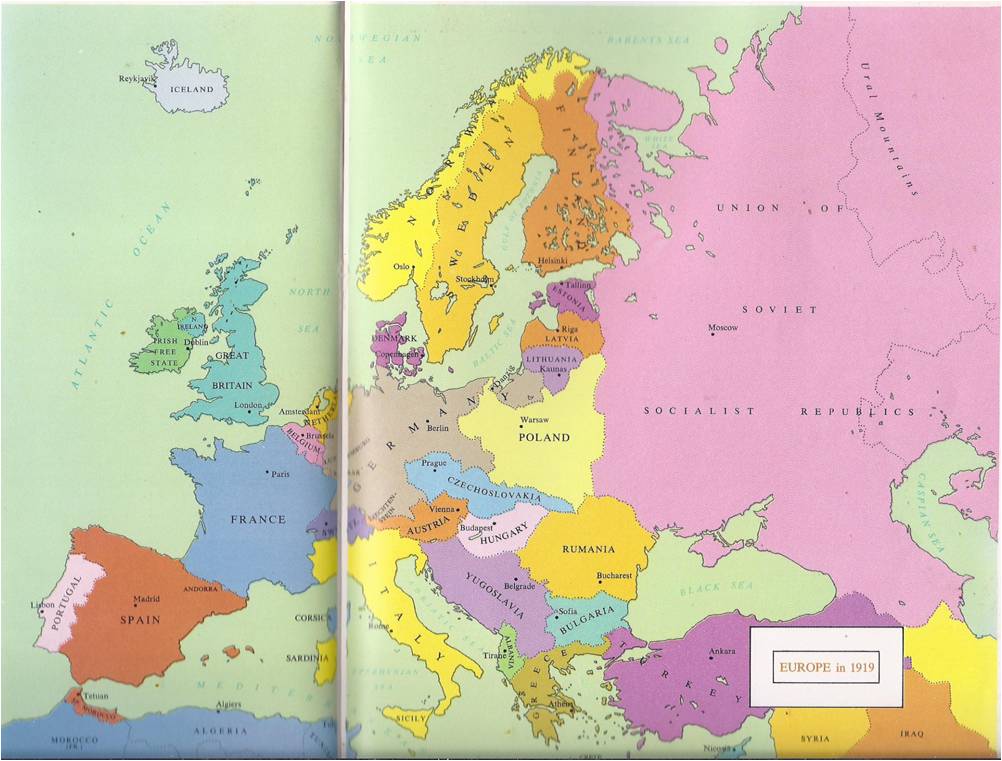

IN THE closing weeks of the war, the Austro-Hungarian Empire came apart. Its subject peoples proclaimed their independence, through “national councils” set up in Paris and London. On November 12, 1918, the last of the Hapsburg emperors, Charles I, abdicated and the next day Austria became a republic. Hungary became a republic a week later. Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia also came into existence and Rumania helped itself to the slice of Hapsburg territory called Transylvania. Before any peace conference could meet, the empire’s former subjects had redrawn the map to suit themselves and the Allies formally recognized the new nations.

THE KAISER ABDICATES

Unlike its ally, the German Empire held firm almost to the end. Earlier in the war, the liberals, democrats and socialists in the Reichstag, Germany’s legislative body, had put off their demands for the sake of national unity. Power had become concentrated in the hands of the generals, led by General Ludendorff.

On September 29, 1918, Ludendorff told the Kaiser that Germany must sue for peace. Furthermore, he urged the immediate formation of a new government along democratic lines, based on the important parties in the Reichstag. The kaiser was astonished, but he soon realized that the army must be in a desperate situation for Ludendorff to suggest such a step. He knew, too, that the proud military aristocrats who commanded the army could not bring themselves to surrender; the task must be left to civilians.

Sadly the kaiser gave his consent and Prince Max of Baden, a liberal nobleman, agreed to head a cabinet that included the socialists. By October it had put through a number of reforms, but the socialists were not satisfied. They threatened to quit the government unless the kaiser abdicated. Meanwhile, as word spread of the disastrous military situation, the German people began to look upon the kaiser as an obstacle to peace. So did the army officers‚ who wanted the fighting stopped before the army broke down completely.

The result was that on November 9 Prince Max told the kaiser that he must give up the throne. “Abdication is a dreadful thing,” Prince Max said, “but a government without the socialists would be a worse danger for the country.” That very day Kaiser Wilhelm signed the necessary papers and crossed the border into Holland, where he was to live quietly until his death in 1942. He had hardly left Berlin when Germany proclaimed itself a republic. Two days later, the fighting stopped.

THE WEIMAR REPUBLIC

The German republic became known as the Weimar republic, because the national assembly which set it up met in the city of Weimar. So, civilians arranged the surrender and the army officers felt that they had saved their honour. They were as much in favour of peace as anyone, but later the story would arise that the undefeated army had been betrayed by panicky civilians frantic for peace at any price.

With the collapse of the German Empire, the puppet states it had taken from Russia at Brest-Litovsk became independent nations, but none of them had a government that really governed and the borders between them were vague. As a matter of fact, all Europe east of France and Italy was close to chaos. The money issued by the various countries was almost worthless and their people were on the verge of starvation. Although conditions in western Europe were somewhat better, they were far from good. To make matters still worse, the winter of 1918-19 was unusually cold. Fuel was scarce and keeping warm was a problem.

Yet, in spite of cold and hunger, in spite of their grief over the men who had been killed in the war, Europeans hoped for a better world. As the year of 1919 began, their hopes centered on one man — Woodrow Wilson‚ the president of the United States.

THE FOURTEEN POINTS

A year before, in a famous speech, Wilson had listed the aim for which the United States was fighting. There were fourteen of them and they became widely known as the Fourteen Points. Millions of copies of the Fourteen Points had been dropped from airplanes flying over Germany, Austria-Hungary and in some instances they had weakened the fighting will of the troops. Wilson did not seek revenge and even the enemy could agree with many of his proposals.

The Fourteen Points expressed Wilson’s faith in democracy and were a direct answer to the challenge of Bolshevism. Wilson agreed with the Bolsheviks that only autocratic countries started wars, but he also believed passionately that the only just governments were those based on the consent of the governed. He wanted to create a world of liberal democracies.

Wilson called for an end to secret treaties between nations and secret dealing by diplomats. He demanded “freedom of the seas” for all nations and asked that all barriers to international trade be removed. He said that all the powers, victors and vanquished alike, should reduce the size of their armies and navies. They should settle their differences in the colonies fairly and withdraw their troops from occupied parts of Europe. Wilson insisted that all European peoples govern themselves and that European boundaries be drawn along national lines. Most important of all, he proposed that an organization of all the world’s nations be set up, to prevent war from breaking out again.

Although the Allied governments had made a number of secret agreements among themselves for carving up conquered territory before America entered the war, they finally accepted most of Wilson’s proposals. France and Great Britain had objections. The French insisted that a statement be added about Germany paying war damages and the British balked at “freedom of the seas.” With these reservations, the Allies were ready to follow Wilson’s lead.

THE PEACE OF PARIS

In January of 1919, Wilson came to Europe, for the peace conference and visited the capitals of England, France and Italy. His tour was a tremendous personal triumph. Wherever he went, huge crowds turned out to cheer him and several times he was almost mobbed. The feelings of all Europe seemed summed up in a sign strung up in Paris: “Honor to Wilson the Just.” For here was something new in history — the head of a great power that had been victorious in war was bringing forth a master plan for peace. Wilson seemed more than a great statesman; he was a saviour who was leading the world into a new era.

Later that month, representatives of twenty-seven nations met in Paris to work out the details of the peace treaties. During 1919 and 1920, five treaties would be signed — the Treaty of St. Germain with Austria, of Trianon with Hungary, of Neuilly with Bulgaria, of Sévres with Turkey and most important of all, the Treaty of Versailles with Germany. These five treaties made up the Peace of Paris.

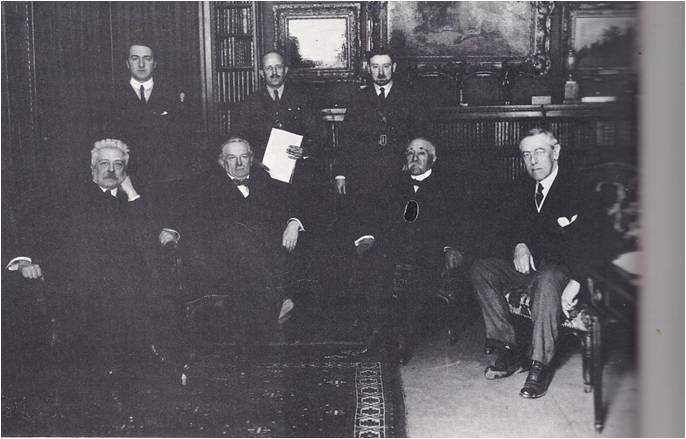

As the conference went on, it became clear that the actual decisions would be left to the heads of the Allied nations President Wilson, Prime Minister Lloyd George of Great Britain, Premier Georges Clemenceau of France and Prime Minister Vittorio Orlando of Italy. The “Big Four,” as they were called, were men of different backgrounds — and different ideas. Wilson, a former professor and college president, was an idealist, but he had little first-hand knowledge of any people except Americans. Lloyd George was a brilliant politician who had made a reputation as reformer, but he had left the conduct of foreign affairs to others. Furthermore, he had promised to “make Germany pay the whole cost of the war.”

The aged Clemenceau, who was known as the “Tiger,” was a fierce patriot whose only concern was to get the best possible bargain for France. As a practical man, he did not think too highly of Wilson’s idealism. He once told a friend, “Moses gave us ten commandments and we broke them. Wilson gives us fourteen — we’ll see.” Orlando, who was also a former professor, was interested only in seeing that Italy was rewarded for its part in the war by being given new territories. As it turned out, he was disappointed; Italy’s claims were not allowed.

THE VERSAILLES TREATY

Wilson fought hard for the establishment of a League of Nations, a permanent international body to settle disputes between nations and keep the peace. The other members of the Big Four doubted that such an organization was practical, but they gave in to Wilson and the charter of the League was written into the Treaty of Versailles. In return, however, Wilson had to compromise on a number of matters; to satisfy the demands of one power or another, the Fourteen Points were considerably weakened and watered down. Wilson was unhappy about this, but he felt that once the League of Nations was set up, it would repair any damage that had been done.

The Treaty of Versailles was completed in three months and parts of it reflected the bitter hatred of the French for their recent foes. France received Alsace-Lorraine, which the Germans had seized in the Franco-Prussian War. France was also to govern the Saar, with its rich coal mines, until 1935, when its inhabitants would vote on whether or not the territory would be returned to Germany. To make sure that Germany lived up to the treaty, Allied troops would occupy the Rhineland, along the Rhine River, for fifteen years.

While the Allies, especially France, feared a revival of German strength, they also feared the new communistic government of Russia. They decided to set up strong buffer states that would serve as a protection against Russia. In assigning territory, the conference tried to carry out Wilson’s aim of drawing boundary lines according to the wishes of the inhabitants of each state, but in many places the population was mixed and the treaty created as many problems as it solved. The new nation of Czechoslovakia, for example, had already set its boundaries so as to include a considerable number of Germans in the Sudeten Mountains. These Sudeten Germans, as they were called, had been subjects of Austria-Hungary and now they wanted to join Germany, but the Allies were determined not to make Germany larger than it had been before the war. They confirmed the boundaries of the Czechoslovakian republic, leaving the Sudeten Germans unwilling citizens of Czechoslovakia.

Poland, which lay between Russia and Germany, was made a large state. To give it an outlet on the sea, the conference added to it a strip of German territory running north to the Baltic. The “Polish corridor,” as this strip was called, cut East Prussia off from the rest of Germany. Danzig, a German port, was made a free city that belonged to no country.

Under another provision of the treaty, Germany lost all its colonies, but instead of letting them be taken over directly by the Allies, Wilson and a South African leader, General Jan Smuts, came up with another plan. The colonies were awarded to the League of Nations, which was to turn them over for administration to one power or another. In this way, France and Great Britain got the best of Germany’s African colonies, while the Union of South Africa received German Southwest Africa. Italy got nothing.

In the Pacific, Japan had gone to war on the Allied side in 1914, hoping to seize islands held by Germany. The treaty gave Japan the right to administer former German possessions north of the equator, while Australia and New Zealand divided those south of the equator. Japan claimed the German leaseholds and sphere of influence in China, but China demanded an end to all foreign rights on its territory. A compromise gave the Japanese half of what they asked for — and left the Japanese unsatisfied and the Chinese outraged.

SCAPA FLOW

The Allies took over the German fleet, now assembled in Scapa Flow, north of Scotland, but before British seamen could board the warships, their German crews deliberately sank them all and so the Germans could say that their navy, like their army, never actually surrendered.

The postwar German army was limited to 100,000 men and the treaty forbade the Germans to have heavy artillery, airplanes, or submarines. Germany was not allowed to draft civilians for military training or to maintain a reserve. The result was that the German army became completely professional and its officers had at least as much prestige as ever.

The war in the west had been fought entirely on the soil of France and Belgium. Both countries had suffered huge losses of life, property and they demanded that Germany pay for them. At the conference, their governments submitted staggering bills. The Belgians claimed that Germany should pay them a sum larger than the entire wealth of all Belgium. The French and the British wanted Germany to pay every penny the war had cost them. Wilson pointed out that Germany could not possibly raise such vast sums and even Clemenceau had to agree. “To ask for over a trillion francs,” he sighed, “would lead to nothing practical.”

The treaty finally stated that Germany must pay war damages, but left it to a future committee to set the exact sum. As a first payment, Germany had to give up most of its merchant fleet, make deliveries of coal and surrender all property owned by German citizens outside Germany. This last requirement ended Germany’s career as an overseas investor.

To justify their demand for war damages, the Allies wrote a special “war guilt” clause into the treaty. This clause bound Germany to accept the responsibility for all damage and loss resulting from the war. It stated that the war had been “imposed on them [the Allies] by the aggression of Germany and her allies.”

When the German people learned of this clause they were indignant. They did not consider themselves responsible for the war and felt insulted to be asked to accept guilt they did not feel. In May, 1919, when the treaty was presented to the German representatives at Versailles, they refused to sign.

At this, the German government was thrown into a crisis. No German was willing to risk the condemnation of his countrymen by setting his name to such a treaty, but someone had to be found to sign it and at last a group drawn from two middle-of-the-road political parties agreed to undertake the hateful duty.

In the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, whose thousands of glittering panels had once reflected the magnificent courts of the French kings, dignitaries from all the Allied nations waited for the Germans to arrive. Two men came in, wearing suits as plain as their names — Mueller and Bell. They looked lonely, almost ashamed. Allowing themselves to be led to a long table, they drew out pens and signed the document which officially ended World War I and unofficially set Germany on a road that would lead to an even more terrible war.