As Rome’s armies marched victorious across the known world and her fleets patrolled the Mediterranean, hundreds and thousands of slaves were shipped back to Italy as cheap and expendable labour for the vast estates of the rich. Many worked in chain gangs under the lash of brutal taskmasters or were sent as shepherds to the milder parts of the country. Others were put into gladiatorial establishments, where a cruel and bloody death was an almost certain fate. In such conditions revolt seemed inevitable and after an unsuccessful attempt in Sicily in 135 B.C., a new revolt, under the leadership of the Thracian, Spartacus, exploded in 73 B.C. An army of 40,000 under Crassus was needed to restore order and 6,000 slaves were crucified as a warning to their fellows. Despite its immediate failure, the revolt hinted that the days of the Roman Republic were now numbered.

One day in June, 73 B.C., seventy-four gladiators broke out of their training establishment at Capua in southern Italy. They armed themselves with weapons stored for training and arena fighting, cut their way through the city and marched across country to Mt. Vesuvius. There near the top they made camp and soon slaves from the towns and farms joined them. The leaders were the Thracian Spartacus and two Gauls, Crixus and Oenomaus and their force included a strong contingent of Gauls and Thracians. From the outset, Spartacus dominated: it was he who had doubtlessly organized the breakout from Capua.

The alarmed authorities sent G. Claudius Glaber, a praetor of the year, who tried vainly to surround and dislodge the rebels. However, the emboldened slaves came down the slopes and roamed about the south, scattering detachment after detachment of troops. Soon they were masters of the whole south and their ranks were swollen with runaway slaves. Indeed by the spring of 72 they made up two armies, one under Spartacus, the other under Crixus.

Such a large-scale slaves revolt was in a strong position only while they held together; as soon as they dispersed they were liable to be captured or massacred; unless they could take over the whole of a defensible and self-sufficient area, their only hope was to get back to their own lands. Spartacus knew that his only course was to maintain a massive force until he was safe from attack by Roman armies and then, to break out. Once out of the peninsula, he and his men might find refuge in mountainous regions or march out of the Empire altogether. These plans were impeded by Crixus and his men, who were lured by the plunder available in the rich cities of the south.

The Roman Senate recognized the need for quick, effective action. The two consuls L. Gellius Publicola and Gn. Lentulus Clodianus were each given an army. Crixus was cornered and routed near Monte Gargano, but Spartacus was too good a general to be so easily caught. No longer embarrassed by Crixus, he decided to march north across the Alps. Somewhere in Picenum two battles were fought. Spartacus defeated Lentulus, then turned and smashed Gellius’ army. The Senate suspended both generals, as Spartacus again moved north.

By then, there were sharp debates in Spartacus’ camp. Should they divide into small bands and steal away over the Alps, or hold together in a force that could break the legions? The men resolved to stay united, while still seeking an escape from the trap of Italy. They turned south. Spartacus is said to have contemplated an attack on Rome, although he knew such a venture could not succeed. In Sicily, however, more slaves would join him in the slaves revolt and he might, found a separate state.

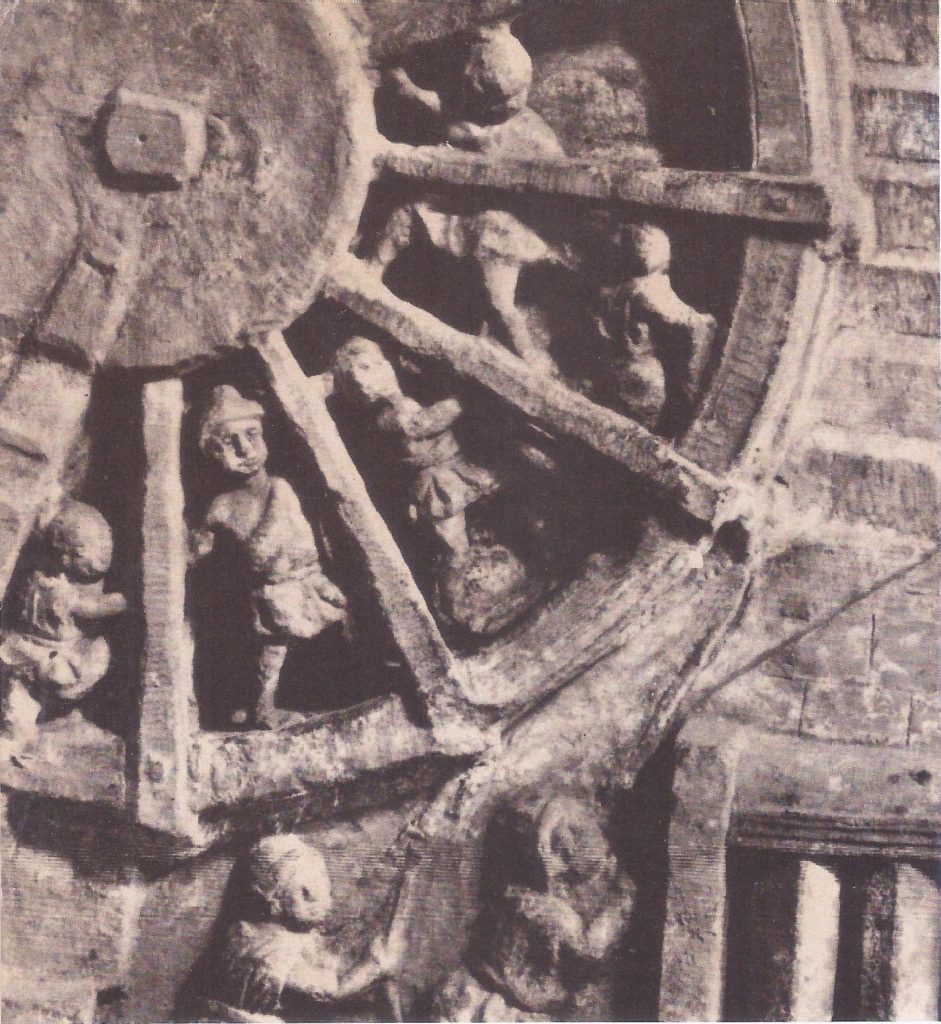

The Senate now appointed M. Licinius Crassus, praetor, as field commander. Crassus, a rich unscrupulous man, had no prestige as a general and he decided to minimize risks. Gathering the remnants of four legions, he added six more, then set out to bar Spartacus from the Strait of Messina. In the battles that followed, the weight of disciplined troops told: Spartacus was driven down to Rhegium but failed to cross into Sicily. How many men the cautious Crassus had mustered was Shown by the extensive fieldworks he then began. A 37-mile-long wall right across the rugged land of Italy’s toe, behind which he planned to hem in th rebels and starve them out. Concentrating his men at one point, Spartacus easily broke through. At last, a really capable general, Gn. Pompeius, appeared on the Roman side. Pompey had returned from subduing Spain and popular pressure made the Senate commission him to go to the aid of Crassus. Spartacus was hoping to seize the port of Brundusium and leave Italy; but his plan was spoiled by the arrival of M. Lucullus with a victorious army from Asia Minor.

In their difficult situation, dissensions inevitably broke out among the rebels. Two Gauls formed a force of their own; and Spartacus had to spend more time and thought on rescuing them from the results of their rashness, than in building his own campaign. When the two Gauls were defeated in the mountains between Paestum and Venusia, Spartacus turned south again. A slight success roused his men to demand battle in hope of a decisive triumph. Now, however, Spartacus finally was beaten; he was killed in battle, and the revolt was crushed. Six months after his appointment, Crassus was able to carry out the masters’ revenge on the slaves revolt and the slaves who had defied them. Six thousand captives were crucified all along the Appian Way from Capua to Rome — the usual punishment for participating in the slaves revolt. Pompey arrived only in time to annoy Crassus by helping to round up fugitives.

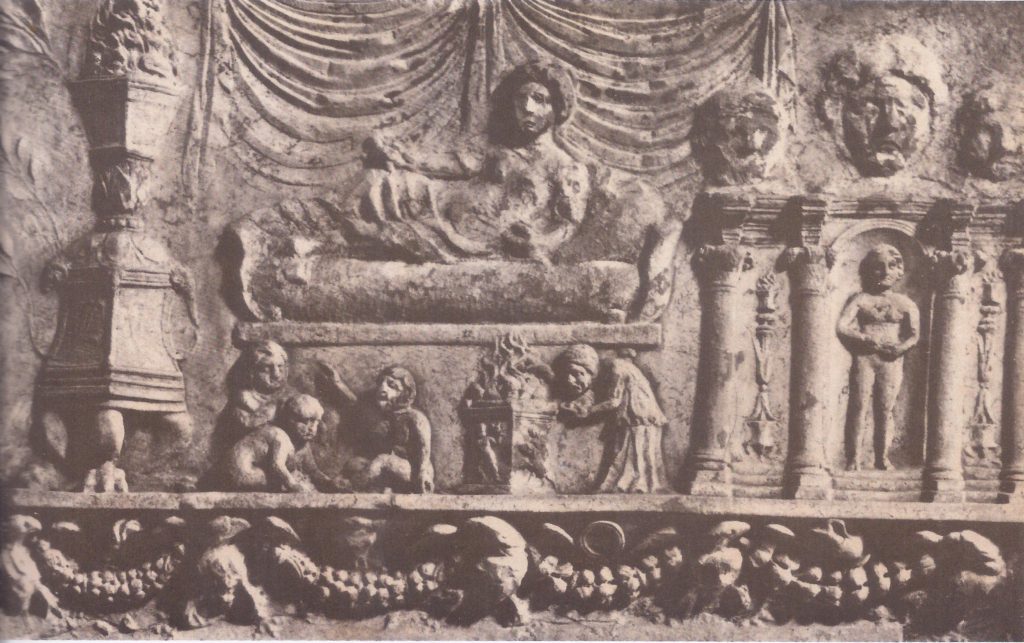

It was fitting that the last great slave revolt was precipitated and led by men who refused to be gladiators; for it was in the bloody combats 0f the arena that the most cruel and debasing aspects of the Roman world were concentrated. The fights derived from Etruscan funeral games; but they were taken over and brutally expanded by the Romans.

Though the generalship of Spartacus made his the most serious revolt, there had been earlier large-scale uprisings. The Mediterranean world was undergoing an acute crisis as the system formed by Alexander the Great was collapsing and Rome was striving to unite East and West in a single empire. As far back as early in the third century B.C. there had been a slave rebellion on the island of Chios and in 279, came a movement to force the wealthy to give up their property, but the Macedonians, as champions of the status quo, intervened. Similar conflicts in Greece led at times to attempts to free slaves for service as soldiers. In 132 came an uprising at Pergamum with a plan for setting up a “City of the Sun,” on an egalitarian basis inspired by Stoic thought; but this time, Rome intervened.

In Italy, not until the second century, with its vast massing of war captives as slaves, did things become serious. The first warnings came from the wilder regions of the south, in Apulia, where slave herdsmen were gathered. By the nature of their work, such men could not be closely superintended; their areas became centres of brigandage (robbery).

Then the storm broke, in Sicily. The dates are obscure. We may assume that the revolt properly crystallized from endemic brigandage. Sicily had become a place where slaves revolt and could hope to disappear and live by robbery; in about 140 a praetor is said to have sent back 917 fugitive slaves, of the slaves revolt, to their mainland masters. The island also attracted criminals and enemies of the Roman order. Jews and Chaldeans, evicted from Rome, seem to have gone there, as did guerrillas from Spain. As bands of desperadoes collected, the countryside became unsafe for unescorted travelers or free Villagers.

Wretchedness and Brutality Provoke the Slaves Revolt

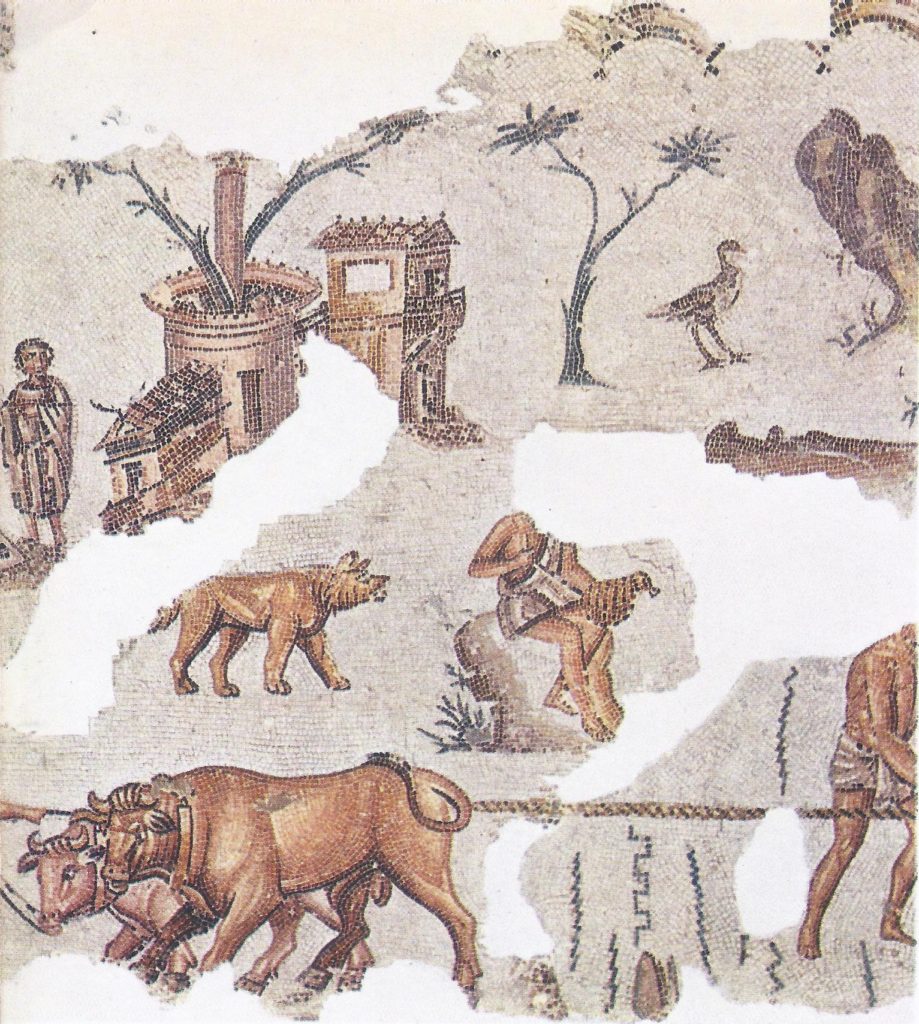

In addition to fugitives, desperadoes and mutinous shepherds, there were large numbers of slaves massed in Sicily for work in the fields; for Sicilian agriculture had grown dependent on slaves. Landlords gave up using free labour and bought slaves, cheap and expendable on account of the wars. To the wretchedness of the latter’s living conditions, was added the brutality of overseers ready to flog the chain gangs. Often, when war prisoners were bought in bulk, men of the same tribe were gathered together and such groups were liable to breed concerted resistance.

A man who became a focus of slave hopes was Eunus, known at Enna as a magician and prophet. He claimed to see the gods and to have been told the future. Sometimes he breathed fire: historians say he did it by hiding in his mouth a pierced walnut full of burning sulphur and tinder.

At last, in 135 a full-scale revolt broke-out and Emma was stormed. Damophilus, a particularly bad master, was tried in the theatre and spoke in his own defense, but was cut down by two leaders without a formal verdict. The assembly proclaimed Eunus as king and he took the name of Antiochus, calling his people Syrians. The workshops or dormitories of the slave gangs were broken open. We are told that prisoners of the rebels who had shown themselves humane were spared. On the whole it seems that the slaves revolt behaved with moderation; the small freeholders, were the ones who were for revenge on the landlords.

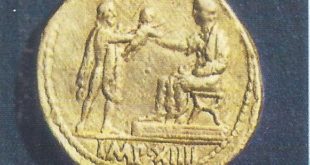

Meanwhile, western Sicily was also in turmoil. Under the leadership of a herdsman, Cleon, the slaves took Agrigentum. Contrary to Roman hopes, the two bands did not clash, indeed they may have acted in concert. Cleon accepted Eunus as king and marched with his brother and some five thousand hillmen to Enna. A praetor sent from Rome levied some eight thousand Sicilians, but was routed by the slaves revolt. Eunus-Antiochus issued his own coins, with the goddess Demeter on one side, a corn ear on the other. Tauromenium, where the Roman commander had let the walls fall into disrepair, was taken. Lack of supplies forced the slaves revolt to abandon their siege of Syracuse, but they captured a hill fortress, Morgantia.

In 134, one of the consuls took over the Sicilian command, but he failed to crush the revolt. Slaves everywhere were stirred by the news of the successful rebellion. In Rome a plot by some 150 was suppressed; severe measures had to be taken against unrest at Minturnae and Sinuessa. In Sicily much confused fighting went on. In 133, a new consul took over; sling-bullets with his name, found at Erma, suggest that he made an assault there. It was not until 132, that the Romans recaptured Tauromenium and then Enna was besieged; Cleon fell. Achaeus had already disappeared; Eunus was caught in a cave. Perhaps because of his sacral claims, he was not executed, but was merely shut in a cell to rot. Flying columns of reprisal combed the island and it is said that some twenty thousand of the slaves revolt, were crucified. Throughout their campaigns the rebels had made no effort to leave Sicily; they had hoped to build there an independent state, with their coins expressing dreams of a fertile earth and a full life.

For a generation, things were fairly calm. Then in 104 the shock of the German invasions reawoke unrest. There were slave risings in Nuceria, then in Capua, then near Capua, when a Roman eques (of the middle class), ruined by love affairs, armed his slaves. The plebeian general Marius, badly needing men against the Germans, forced the Senate to decree the release of all citizens of allied states, held as slaves in the provinces. The Sicilian landowners were infuriated; and after freeing some four hundred men, the governor Nerva refused to comply further. A small revolt in the west was broken by treachery. Then on the south coast the slaves defeated a Roman force, mustered six thousand men and formed a regular army. Salvius, chosen as leader, took the title of king and threatened Morgantia. The town was saved, but Nerva failed to carry out his promise to free the loyal slaves there and the latter left to join Salvius. Meanwhile, another revolt came in the west under Athenion, who, though defeated, joined Salvius and remained a considerable threat.

So far, only Roman garrison troops had been involved in Sicily; but the Senate now sent an army of seventeen thousand under the new governor, Lucullus. It included men from as far afield as Thessaly and Bithynia. The slaves, though still outnumbering the Romans, were in the end beaten by the discipline and organization of the legions. Athenion escaped capture by pretending to be dead. Then delays by Lucullus gave the survivors time to regain courage. Lucullus was beaten off, displaced and finally, exiled. Then in 101 the German menace in the north was ended. Manius Aquilius, an energetic and experienced campaigner, was sent to Sicily. Salvius was dead and Athenion was in sole command, but now he too, was killed and Aquilius remorselessly rooted out the fugitives. Prisoners, sent to Rome, killed one another rather than be driven into the arena to amuse the mob by fighting wild beasts. There were no more rebellions in Sicily.

On the mainland, unrest grew. By 73 B.C. there were many elements to encourage slaves in thinking an opportune moment had come. For more than half a century the Roman state had been rent by Violent inner conflicts. Between 132 and 82, seven consuls, a praetor and four tribunes of the plebs were assassinated or died fighting other Romans. In 90 came the Social War, a revolt of other Italians demanding fuller rights; in 82 there was civil war that ended in Sulla’s dictatorship, with its many prescriptions and legal murders; Sulla’s death in 78 brought more political conflicts in Rome.

At the same time there were threats from without. Around the turn of the century came the big German invasions; in Spain sustained resistance was led by Sertorius (murdered in 72); and Pompey on his way to fight there in 77 had to quell a large rising in Transalpine Gaul. At sea, there were the wars against the pirates. In the east, Rome was challenged by Mithridates (not defeated until 66). Further, the free peasantry who had supplied the manpower for the legions was being reduced by war and the encroaching estates of the big landlords, a situation that underlay all the ceaseless social and political conflicts in Rome itself. At such a time, slaves might well have hoped to break out of the system and win the wilder parts of Gaul, Thrace and beyond.

Yet, despite the apparently favourable conditions, Spartacus’ revolt also failed. A strong and determined body of slaves could begin well, but they had little chance of long resistance to regular troops backed by all the resources of the cities. Their only hope was to move quickly into remote areas; staying in Italy ensured their final defeat.

Did the slaves who rebelled over the years have any social program beyond the desire to become free men? It is argued that in Sicily, by choosing kings, they showed the wish to build the same sort of society that existed elsewhere in their world, but Eunus was a prophetic character; and the slaves may have used the term ‘king’ to mean no more than leader.

Eunus’ coins with their image of farming prosperity suggest an ideal of an earthly paradise that must have inspired his followers, just as his prophecies must have stirred them. The Romans clearly feared his propaganda. In 133 the Senate sent an embassy to placate the goddess Ceres (Demeter) of Enna; and walls were built round the precincts of the temple of Jupiter Aetnaeus, apparently to deprive the slaves of a source of religious enthusiasm.

In the second Sicilian revolt, the slaves fought under the aegis of the Palici, Sicilian deities whose shrine had been founded by an early Sicilian patriot. We know from many sources that the lower classes everywhere were stirred at this time by dreams of world-end and world-renovation — and such dreams must have been voiced in Sicily and in the camps of Spartacus. Undoubtedly, while some slaves responded to them, others thought only of escape and revenge.

While the slave revolts had few direct political consequences, their social and economic effects were of great importance. Sicily proved that to work the land with large slave gangs was dangerous and more and more landlords turned to tenant farmers rather than slaves for the cultivation of their estates. Columella, writing under Nero, recommended the use of slaves on the home farm, where they could be well supervised. The younger Pliny, a generation later, had much to say of troubles with defaulting tenants and mentioned that he never used slave gangs in chains. The third-century lawyers show the same sort of mixed farming. We get a picture of skilled slaves working on the home farm (attached to a residential villa) at jobs like vine-dressing, with arable farming given over to free tenants.

The slave revolts thus certainly played a large part in the supplanting of the free peasant farmer by the free tenant liable to turn into a share cropper and sink in status. They proved the perils of attempts to till land by slave gangs. It is perhaps noteworthy, that no attempts were made to build up big workshop units of slaves in the crafts and manufactures; it may be significant that in 134, there was much trouble, as we noted, at Minturnae, an industrial town. In the late Empire, with growing insecurity, there was a fall in slave prices, but no effort was made to revive gang work and the social and economic position of the slaves began to approach that of tenants, who in turn found their lot worsened. Thus, the way was opened to developments that slowly transformed the ancient world into the feudal economy of the Middle Ages.