IN Europe as in America, the leading democratic nations — Great Britain and France — faced the problems of the great depression. In those nations, too, the question arose: Could democracy survive, or would it give way to totalitarianism? Would the people turn instead to fascism or communism?

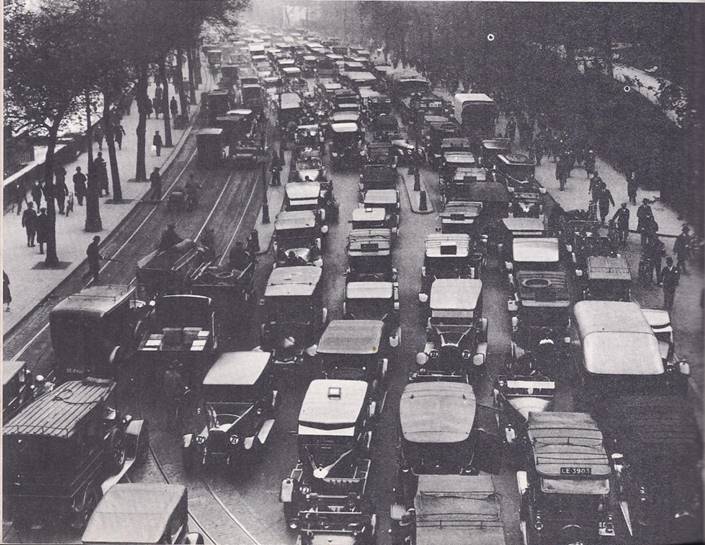

Although Britain had a brief period of prosperity immediately after World War I, of all the world’s democracies, it was struck hardest and soonest by the depression. For Britain had a special problem. A highly industrialized country, it lived by its exports. It sold manufactured goods and coal to other countries and imported its food.

Even before the war, Britain had begun to lose its markets. Other countries were making wool and cotton cloth, which was one of Britain’s most important exports. New fuels were developed that were replacing coal. More and more countries were using high tariffs to keep out foreign goods. After 1918, the situation became even worse. The fact that Britain had long been an industrial country was now working against it. Its machinery and manufacturing methods were old-fashioned and could not compete with the modern machinery and methods of other lands. Exports fell, factories shut down and millions of Britons were out of work.

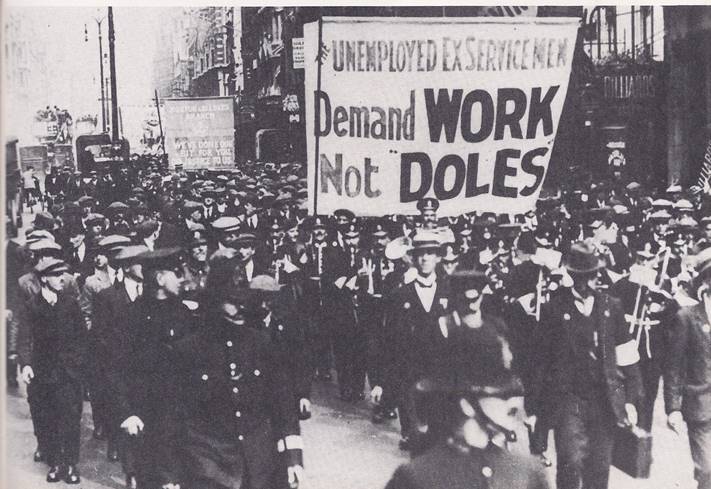

Britain had had unemployment insurance as early as 1911. Now the payments were increased and the unemployed went “on the dole,” as they called it. The government also provided old-age pensions and some medical and housing aid, but the people felt that the unemployment and other benefits were too small and they were dissatisfied. They began to turn to the Labour party. Up to this time, Britain’s strongest political parties had been the Conservative party and the Liberal party, with the Labour party a poor third. In 1922, the Labour party became second only to the Conservatives. Two years later it was elected and Britain had its first Labour government. Ramsay MacDonald was named prime minister.

The Labour party had been formed in 1900 by trade unionists and socialists. It stood for the establishment of socialism, but gradually and by democratic means. It was far from the revolutionary parties of other countries and nothing at all like the Communist party of the Soviet Union. Once in power, the Labourites made no attempt to establish socialism. They recognized the government of the Soviet Union and negotiated several treaties in the hope that the Russians would buy British goods. They extended unemployment insurance, started public works projects and gave more aid to housing.

Because of their small majority in Parliament these mild measures were the best they could do for the unemployed. Then the newspapers published a letter that was supposed to have been sent by the Communist International to British labour groups, instructing them to prepare for a revolution. The letter was later proved to be a forgery, but when it was first published it frightened many Englishmen. After all, the Labourites were for socialism and socialism was the next thing to communism and Britain wanted none of that. By 1924 the Labourites were voted out and the Conservatives were in.

For five years the Conservatives controlled the government. Stanley Baldwin occupied No. 10 Downing Street — the house in London which was always reserved for the prime minister. The Conservatives placed tariffs on certain goods‚ but this did little to improve trade and business.

The coal mines, particularly, were in trouble and the price of coal kept falling. When the mine owners tried to cut wages and increase the working day from seven to eight hours, the miners went on strike.

In May of 1926, a number of other trade unions went on strike in support of the miners. Although the strike was called a “general strike,” and transportation and other important industries were tied up, no more than half of Britain’s 6,000,000 organized workers walked out. Declaring a state of emergency, the government called for volunteers to operate essential services — and got them. In nine days, the general strike was over. The miners remained out for more than seven months, but in the end they were forced to accept the owners’ terms.

The following year, the Conservatives passed laws making general strikes illegal and restricting unions in a number of ways. They also passed laws providing for pensions for workers who had reached the age of sixty-five and pensions for the widows and orphans of workers who died before the retirement age, but business conditions grew worse instead of better and unemployment rose throughout 1928.

As Britain prepared for the general election of 1929, the Liberal party called for a vast program of public works to end unemployment. The Labour party went much further. It called for the nationalization — that is, government ownership — of certain industries, much higher taxes on the rich and other drastic reforms. The Conservatives proclaimed that they were the only party that could stop socialism and put the nation’s economy on a sound basis.

The election returned the Labour party to power and again Ramsay MacDonald was prime minister, but again the Labourites had not won enough seats in Parliament for a majority. They were able to put through a few of the things they had promised during the election campaign, but not the sweeping reforms their followers wanted. For now the world-wide depression had struck with full force and by 1931 Britain had 2,600,000 unemployed. As more and more people went on the dole‚ the government kept putting more and more money into the unemployment insurance fund. At the same time, it was receiving less and less in taxes. The result was that the nation was deeply in debt and its financial situation was serious. A committee of experts recommended that the government cut down on spending to save the country from financial ruin. This meant lower dole payments, lower pensions, lower salaries and fewer social services. MacDonald decided to follow the committee’s recommendations and the Labour party split wide open.

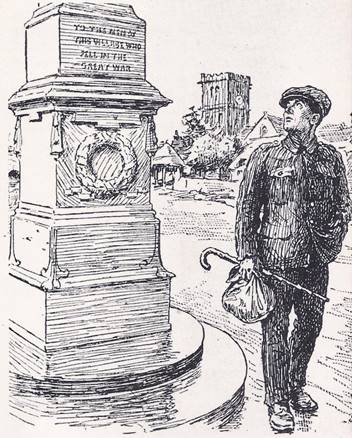

Most Labourites were deeply shocked. They remembered that MacDonald had been one of the founders of the Labour party. Born to a poor family in Scotland, as a young man he had come to London, where he became a socialist. He was also a pacifist. When World War I broke out, he took a firm stand against it, even though this made him unpopular for a time. Then he worked his way up to leading positions in the Labour party and was considered a true representative of the working class. Now he was calling for measures, such as a cut in the dole, that would hit hardest at the workers. He was betraying them and his party; he was betraying his principles; he was a traitor. He and the ministers who supported him were expelled from the Labour party.

The Labourites could no longer stay in power and MacDonald organized a new government. Called the National government, it was a coalition of members of Britain’s three parties. One of the first things it did was to take Britain off the gold standard. In the election of 1931, the National government won an overwhelming victory. Although the Conservatives were by far the strongest party in Parliament, MacDonald continued as prime minister. The National government was successful in balancing the budget and in time it raised dole payments somewhat. Like the New Deal in the United States, it was unable to solve all the problems of the depression, but the nation did not collapse and there was never any danger of Britain going communist or fascist. Britain’s communist party was small. Britain had its own fascist party, but it, too, never attracted many members and had little influence.

In 1935, Ramsay MacDonald resigned and Stanley Baldwin, a Conservative, moved back to No. 10 Downing Street. A year later, King George V died and the Prince of Wales took the throne as Edward VIII. When Baldwin and his ministers refused to approve Edward’s marriage to an American woman who had been twice divorced, Edward gave up the throne to King George VI. Parliament, acting through its ministers, had shown once again that it was the real power in the British government.

An even more important event had taken place in 1931. That year, Parliament approved the Statute of Westminster. It made the dominions — Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the Union of South Africa — legally equal to Great Britain and they could govern themselves as they chose. No law passed by their parliaments could be set aside by Great Britain, even if it conflicted with a law passed by the British Parliament. The British Empire had become the British Commonwealth of Nations and Great Britain was not the head of it, but merely a member, along with the dominions.

During the depression years, Britain not only followed its long tradition of democracy, but strengthened it. Before many years would pass, Britons would be fighting and dying to preserve it.