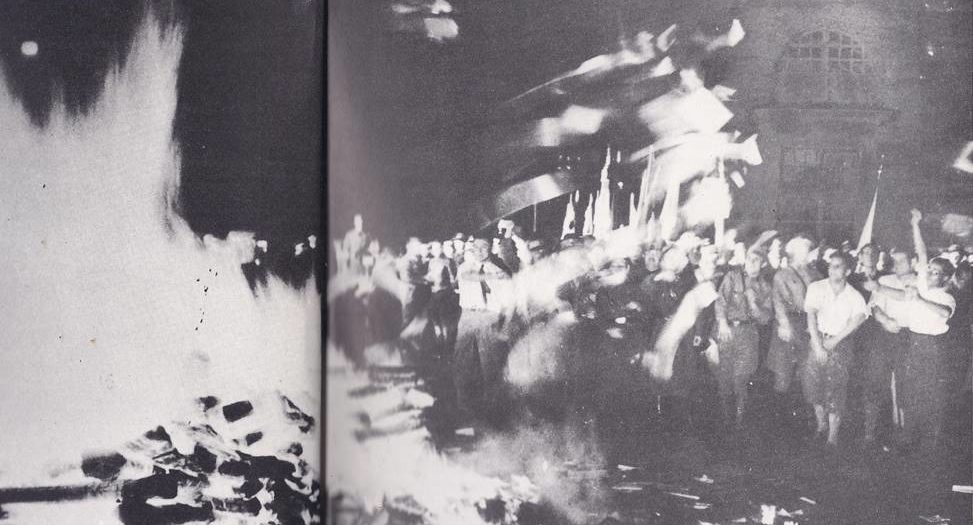

IT WAS almost midnight in Berlin — a strange hour for a parade in any city, but down the street called Unter den Linden paraded thousands of students, carrying torches that flickered in the darkness. In the big square near the University of Berlin, they gathered around a great pile of books. They cheered as the books were set on fire and flames rose toward the sky. For this was the night of May 10, 1933 — less than five months since Hitler had become head of the government — the night when books were being burned in a number of German cities. These were “subversive” books, “un-German” books — or so the Nazis said. They were written by more than 160 writers, including Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann, Jack London, Helen Keller and H. G. Wells.

In the light of the bonfire, Dr. Goebbels, who was now Hitler’s propaganda minister, spoke to the students. “The soul of the German people can again express itself,” he said. “These flames not only illuminate the final end of an old era; they also light up the new.”

There was no doubt that the “old era” had ended and that the “New Order,” as Hitler called it, had come to Germany. As month followed month, Hitler gained more and more control of Germany and its people. He outlawed all political parties but his own. The state, he once said, is the Nazi party. He wiped out the trade unions. He made life more difficult for the Jews. Hitler would decide how Germans lived, worked, worshiped and even thought. He took Germany out of the League of Nations. He made it clear that he would not abide by the Treaty of Versailles and would re-arm. Germany would again become a great military power.

Yet, some Nazis were still not satisfied. Among them was Ernst Roehm, the leader of the stormtroopers. There were now two and a half million of them and Roehm wanted them to become the basis of a new regular army. Besides, Roehm had taken seriously Hitler’s socialistic talk. He called for a “second revolution” that would give Hitler’s loyal followers, especially the storm troopers, a chance to get their hands on the wealth of the big industrialists and landowners. As for the storm troopers themselves, they had committed all sorts of crimes for Hitler and now they wanted their reward.

Hitler had no intention of replacing the regular army and the aristocrats who led it. After all, the storm troopers were not trained, disciplined soldiers. They were gangs of hoodlums whose specialty was street fighting. They did well enough at bashing in the heads of Jews or breaking the bones of Communists and Socialists‚ but that was all. Nor did Hitler have any intention of bringing real socialism to Germany. Although he was rapidly gaining control of the economy of the country, he did not interfere with the profits of the industrialists or break up the holdings of the landowners.

Hitler discovered that Roehm was even doing a little political plotting, trying to win a stronger position for himself in the Nazi government. Conferring with Goering and Himmler, Hitler decided to kill Roehm and his closest followers. This would also be a good opportunity for Hitler to kill some other people who might someday prove troublesome. The job would be done by the SS men and special police under the direction of Goering.

On June 30, 1954, they struck in the “blood purge” that shocked the world. Roehm was thrown into a prison cell and when he refused to take his own life, was shot by two SS officers. General von Schleicher, a former chancellor of Germany, was shot down in the doorway of his own home, as was his wife. Some of the people who died that day were shot in groups, like the 150 storm troopers who fell before a firing squad in Berlin. Some were shot because they knew too much about Hitler’s past. One man was even shot by mistake. He was a Munich music critic named Dr. Willi Schmid. He was killed as he was playing the cello in his study, while his wife and two small children were in the next room. He had been mistaken for Willi Schmidt, a storm troop leader. Schmidt, too, was shot. Hitler claimed that only 77 persons died in the purge but others estimated that the number was anywhere from 400 to 1,000.

The purge left Hitler stronger than ever. Little more than two months later, on August 2, the eighty-seven-year-old President Hindenburg died. Hitler immediately took over the powers of the president, but not the title. He called himself Fuehrer and Reichs Chancellor and ordered every man in the army to swear an oath of allegiance to him:

“I swear by God this sacred oath, that I will render unconditional obedience to Adolph Hitler, the Fuehrer of the German Reich and people, Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces and will be ready as a brave soldier to risk my life at any time for this oath.”

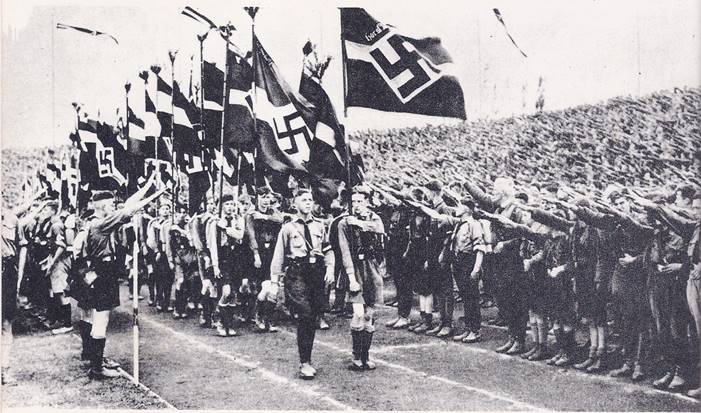

Hitler now had complete power and on August 19 he asked the German people to vote their approval of his dictatorship. More than 38 million Germans — 9O per cent of the voters — voted in favour of Hitler. Four and a quarter million opposed him. It was true that the voters were carefully watched by the Nazis and that many of them may have voted for Hitler out of fear. Nevertheless, the fact remained that the vast majority of the German people approved of Hitler and what he had done.

Hitler himself felt that he had the enthusiastic support of the people. About two weeks after the voting, 30,000 members of the Nazi party met in Nuremberg for a victory celebration. They greeted Hitler with the Nazi salute, shouting, “Heil Hitler! Heil Hitler! Sieg Heil!” That day Hitler announced:

“The German form of life is definitely determined for the next thousand years. The Age of Nerves of the nineteenth century has found its close with us. There will be no other revolution in Germany for the next one thousand years!”

Nazi rule of Germany would last considerably less than a thousand years; it would end with smashed cities and Hitler himself a suicide. Meanwhile, however, he was in full control and he was carrying out the plans he had laid down in Mein Kampf. In September of 1935, the so called Nuremberg Laws were passed against the Jews. A Jew was defined as anyone who had more than two Jewish grandparents, and a Jew could not be a German citizen. While Jews no longer had the privileges of citizenship, such as voting and holding office, they still had to obey the laws of the state. Marriages between Germans and Jews and between Germans and half-Jews, were forbidden. Jews were also barred from a number of professions, businesses and much of their property was seized by the government and the Nazi leaders.

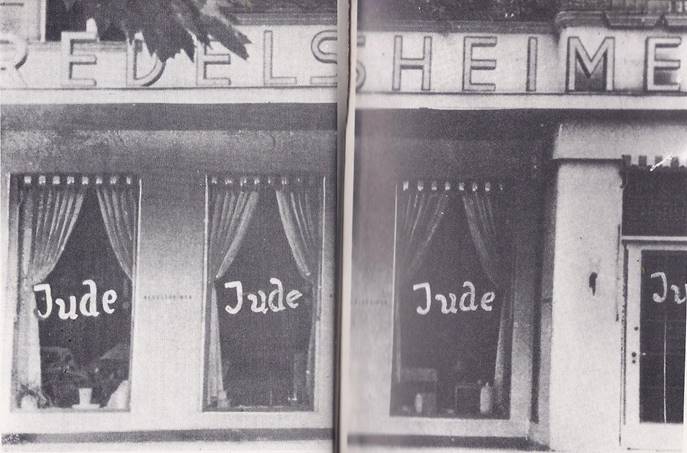

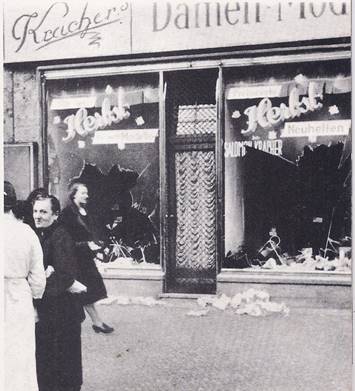

Unable to make a living, thousands of Jews left Germany. Those who could not get away saw signs going up all around them: “Jews Not Admitted”–“No Jews Allowed”-“Jews Strictly Forbidden in This Town.” It became almost impossible for Jews to buy food and medicine. Then, in November of 1938, came what the Nazis later called the “Week of the Broken Glass.” A young Jewish refugee had shot and killed a member of the German Embassy in Paris. In revenge for this, the Nazi leaders sent out orders to the police to organize “demonstrations” of Nazi party members and SS men against the Jews. They were to destroy Jewish homes, businesses, synagogues and there was to be no interference from the police. The orders stated that “as many Jews, especially rich ones, are to be arrested as can be accommodated in the existing prisons.”

On the night of November 9, these orders were carried out. The windows of thousands of Jewish shops were smashed and broken glass lay in the streets. The shops were then looted and destroyed. Meanwhile, houses and synagogues were burned to the ground. Thousands of Jews were arrested and hundreds were murdered. On top of this, the Jews of Germany were forced to pay a fine of one million marks. The Nazi government also issued decrees that confiscated most of the property of Jews and closed almost all businesses and professions to them.

There had been persecutions of Jews in Germany before this and there had been restrictions, such as the Nuremberg laws, but with the Week of Broken Glass, Germany began its real attempt to eliminate Jews from the country and even from the world. This attempt would lead to the horrors of the concentration camps, where men, women and children were worked and starved and tortured to death. It would lead to the gas chambers, where men, women and children were put to death by poison gas. It would lead to corpses piled up and burned in furnaces and tossed in heaps in ditches. It would lead to the death of 6,000,000 Jews.

Nor were the Jews the only ones persecuted. Hitler was determined to wipe out all Communists and Socialists — in fact, anyone who had the slightest objection to the Nazis and what they were doing. The task of spying on people, arresting them and torturing them for confessions was given to the Geheime Staatspolizei‚ the Secret State Police. Better known as the Gestapo, it became dreaded and feared throughout Europe. Unlike the usual kind of police, the Gestapo was responsible to no courts and had to obey no laws. Their job was to carry out the wishes of the Nazi leaders. In the words of one Nazi, “as long as the police carries out the will of the leadership, it is acting legally.” The concentration camps were run by the black-shirted SS men. The guards were the toughest of the SS men — the Death’s-Head units, whose insignia was a skull and crossed bones.

The rule of the Nazis extended over everyone, even children. Beginning at the age of six, boys and girls were forced to join various organizations of the “Hitler Youth.” They had no choice. Parents who interfered in any way were imprisoned. When a boy reached the age of ten, he took this oath:

“In the presence of the blood banner, which represents our Fuehrer, I swear to devote all my energies and my strength to the saviour of our country, Adolph Hitler. I am willing and ready to give up my life for him, so help me God.”

Girls were taught that the chief duty of women was to have children for Nazi Germany. Boys were given military drill and went hiking with rifles and heavy packs. When a boy reached the age of eighteen, he entered the Labour Service or the army. The army was the real centre of German life under the Nazis, for Hitler preached that war was the greatest glory of man, and Hitler needed war; he and the Nazis could not survive without it. Only war and conquest could save the German economy.

In time, Germany would attack. Meanwhile, conditions became somewhat better for the German People. It was true that the workers were controlled by Hitler’s Labour Front. They had to work where and when they were told. It was also true that, without labour unions, workers had to take whatever pay they were offered. While profits were rising, wages were falling. Still, there were jobs to be had, even if the pay was low. As for civil liberties, Germans had never had much political freedom, except under the Weimar Republic. They felt that, if they had lost their freedom, they had also lost the “freedom to starve.”

So, while their Jewish and anti-Nazi neighbours were dragged off to concentration camps, most Germans were satisfied enough with the Nazis. The shrieks of the tortured and the moans of the dying were drowned out by the tramp of soldiers through the streets, by the shouts of “Heil Hitler!”, by the propaganda speeches that poured from loudspeakers, by the wheels of factories busily grinding out instruments of death. Under the flag of the swastika, led by their Fuehrer, the master race was preparing for war.