WHEN Franklin Delano Roosevelt was nominated in 1932, he was fifty years old. A fifth cousin of former President Theodore Roosevelt, he came of a wealthy family. He grew up on a large estate at Hyde Park, New York, overlooking the Hudson River. At the age of twenty-four he married Eleanor Roosevelt, a distant cousin and a niece of Theodore Roosevelt. Several years after graduating from Harvard and studying law at Columbia University, he entered politics and was elected to the state senate. In the presidential campaign of 1912 he supported Woodrow Wilson, who named him assistant secretary of the Navy. In 1920, Roosevelt ran for vice president, but he and his running-mate, James M. Cox, lost the election to Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge.

Even so, Roosevelt had become nationally known and it looked as though he had a bright future in politics. Then, less than a year later while on vacation, he fell ill of poliomyelitis. At first he was paralyzed from the waist down, but slowly, painfully, he fought his way back to health. He would never be able to walk normally and he would be forced to use a wheelchair most of the time. He learned to get about with the aid of braces on his legs, leaning on canes or crutches. In 1924 he made his first Public appearance since his illness. He hobbled on crutches to the speaker’s platform at Madison Square Garden in New York, where he placed Alfred E. Smith’s name in nomination before the Democratic presidential convention. The cheers of the audience were as much for Roosevelt as they were for Smith.

HAPPY DAYS ARE HERE AGAIN

Roosevelt’s battle against illness had left him a changed man. Francis Perkins, who later became his Secretary of Labour, said that he “emerged completely warmhearted, with humility of spirit and with a deeper philosophy. Having been in the depths of trouble, he understood the problems of people in trouble. Although he rarely, almost never, spoke of his illness in later years, he showed that he had developed faith in the capacity of troubled people to respond to help and encouragement.”

Roosevelt was still not sure, however, that he would return to politics. In 1928, when he was asked to run for governor of New York, he replied, “I’m not well enough to run. It’s out of the question,” but when Alfred E. Smith told him that the Democrats could not win without him, he changed his mind and campaigned vigorously. He was elected, served two terms and in the hot July of 1932 was nominated for President. Then he did something no candidate had ever done. He traveled by plane to Chicago to give his speech of acceptance before the convention. In the speech, he said, “I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people.”

A new deal. . . The American people liked the sound of those words. They seemed to offer hope, a promise of action and better times to come. Indeed, Roosevelt was already showing signs that he would do things in a new way. He had gathered about him a group of advisers most of them bright young college professors, who quickly became known as the “brain trust.” Roosevelt met with his brain trust, planned speeches and smiling and confident went out campaigning for the New Deal, while bands played “Happy Days Are Here Again.” He spoke of aid for the “forgotten man” and said that “the country demands bold, persistent experimentation.”

THE BANK HOLIDAY

At the same time, except for his stand on the repeal of prohibition, Roosevelt was not very definite about what his policies would be. Elmer Davis, a prominent journalist, complained that what Roosevelt meant, if anything, “is known only to Franklin D. Roosevelt and his God.” Walter Lippmann‚ a nationally known columnist wrote that Roosevelt “is no crusader. . . . He is a pleasant man who, without any important qualifications for the office, would very much like to be President.” Roosevelt did not seem to mind. He kept smiling and campaigning and the bands played on.

Hoover also campaigned. He pointed out that the depression affected every country in the world, and that the United States could not escape it. If the government were given too much authority, it might mean the end of freedom in America, but the people were tired of Hoover. They elected Roosevelt, 22,821,000 votes to 15,761,000‚ and gave the Democrats a large majority in both houses of Congress.

The election was held in November of 1932; Roosevelt would not take office until March 4, 1933. During those months, Hoover fought desperately to save the nation’s banks because of the depression, some banks had failed and many others were in danger. Fearful of losing their money, people began withdrawing their savings, which made the situation worse.

When Hoover asked Roosevelt’s cooperation in acting on the banking crisis, Roosevelt refused. He believed it would be wrong for him to take part in the government before he was actually president. Besides, his ideas were different from Hoover’s and he did not want to tie himself down to Hoover’s policies. A number of states declared bank holidays, closing their banks for a limited time while steps were taken to save them. On the morning of March 4, inauguration day, Hoover learned that the country’s entire banking system had broken down. Hoover said, “We are at the end of our string. There is nothing more we can do.”

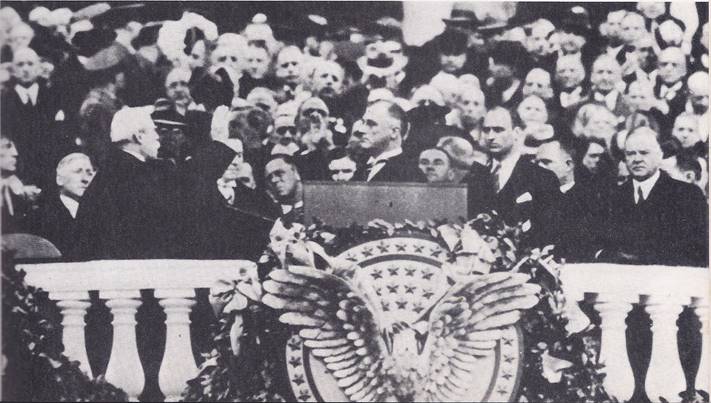

Later that chilly day, while the nation listened by radio, Roosevelt stood at the east front of the capitol in Washington and took the oath of office. The sky was gray and cloudy, as if to emphasize the nation’s desperate situation, but Roosevelt seemed full of confidence as he made his inaugural address.

“This great nation,” he said, “will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper. So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself — nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance. . . . This nation asks for action and action now. . .”

His voice was strong and clear, his words stirring. They made people feel that he would indeed take action and get things moving again. Among his listeners in the crowd at the capitol was one of the men who had been working day and night, snatching sleep whenever they could, trying to save the banks. He, too, was stirred by Roosevelt’s words, but he knew the difficulties ahead. Action . . . action now. . . . “Yes,” he thought, “but how, how, how?”

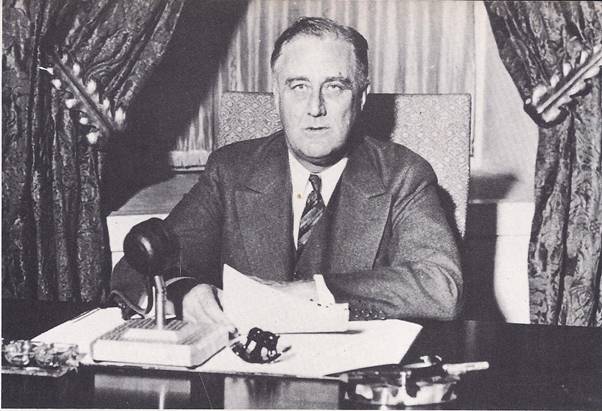

He — and the nation — soon found out. During his first week in office, Roosevelt declared a national bank holiday, called Congress into special session, got permission for stricter control of banking money and had worked out a plan for reopening the banks the following week. On Sunday, March 12, he made the first of his many “fireside chats”– informal radio talks to the people of the nation. In this one he explained what was being done to reopen the banks and how the people could help.

THE FIRST YEAR

That was only the beginning. During the first year of the Roosevelt Administration, Congress passed a number of important bills in quick succession. The Agricultural Adjustment Administration, known as the AAA, was set up to raise farm prices. Farmers were to be paid not to plant a certain portion of their fields, or to plow under some of the crops already planted. The Federal Emergency Relief Administration, or FERA, distributed Federal money for the relief of the unemployed. The Civil Works Administration, or CWA, gave work relief to unemployed men. The Civilian Conservation Corps., or CCC, did two things — it aided unemployed young men and helped to conserve natural resources. Work camps were set up in forests in various parts of the country, where young men between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five worked on reforestation projects, fire prevention, the building of roads and insect control. They were given food, lodging, and $30 a month in cash. Twenty-two dollars of their pay was sent to their families.

The Tennessee Valley Authority, or TVA, was established to build dams in the Tennessee Valley and to sell electrical power at low rates. The aim was to develop the entire basin of the Tennessee River, an area covering 41,000 square miles, on which lived 3,000‚000 persons. It would also provide a “yardstick” to measure the fairness of the prices charged by private power companies.

The most important bill put through by the New Deal in 1933 was the National Industrial Recovery Act, which set up the National Recovery Administration, or NRA. President Roosevelt himself said when it was passed, “History probably will record the National Industrial Recovery Act as the most important and far-reaching legislation ever enacted by the American Congress. It represents a supreme effort to stabilize for all time the many factors which make for the prosperity of the nation and the preservation of American standards.” Actually, the NRA was an attempt to please both industry and labour; to raise both prices and the wages of the poorest-paid workers.

Each industry was to draw up a code for itself, setting rules of fair competition, as well as the maximum number of work hours and the minimum pay for its employees. The government had to approve the codes. If any industry could not agree on a satisfactory code, the government would draw one up. To allow industries to make agreements on prices, the anti-trust laws were suspended. Since industry was being permitted to organize, labour was given the same right. Under Section 7a of the National Industrial Recovery Act, employees were given “the right to organize and bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing,” and were to be “free from the interference, coercion, or restraint of employers of labour or their agents.” In other words, Section 7a gave workers the right to organize unions and it opened the way to unions in many industries.

The government issued posters, placards, and stickers with the NRA symbol, a blue eagle and the slogan: “We do our part.” The Blue Eagle was displayed everywhere and there were NRA parades and meetings with speeches and brass bands throughout the country. No one knew exactly what the NRA would accomplish. Some people were puzzled by it and some opposed it, but many were enthusiastic and cheered the parades and the speeches.

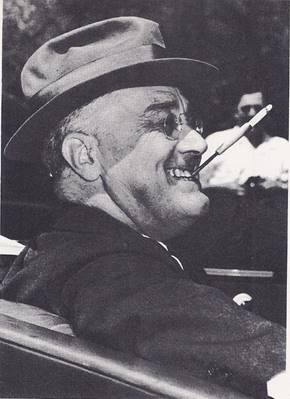

By the time Congress adjourned, the New Deal had made an enormous change in American life. The AAA, the FERA, the CCC, the TVA, the NRA — none of these had been even dreamed of during Hoover’s administration. Americans could now drink beer and light wines. Congress had voted to repeal Prohibition before Roosevelt became President and the states would not ratify it before December of 1933, but beer and light wines were now legal. Washington boiled with excitement as experts and advisers flocked to the city to help set up the new government agencies. Few Americans were not familiar with the sound of Roosevelt’s voice in his fireside chats, with his smile and the jaunty tilt of his cigarette holder. They were also becoming familiar with his wife, Eleanor Roosevelt. Unlike other first ladies, she traveled about the country, speaking, writing, working for causes that interested her.

The United States was a changed country — and there were more changes to come.