Dictators came to power in many European countries during the twenty years following World War I. About 9:20 P.M. on February 27, 1933, the rumble and clang of fire engines echoed through the heart of Berlin, capital city of Germany. Down the broad avenue called Unter den Linden the trucks roared toward the Reichstag building where the German legislature met, but the firemen were too late; they could not check the flames which licked savagely from the windows. Within a few hours the big building was no more than a smoke-stained skeleton.

The Reichstag fire was a grim prophecy of what lay ahead for Germany. Investigation proved that the fire had been started at many points in the building at the same moment; but by whom? Police claimed they had the answer when they arrested a dull-witted fellow found poking about the fire-gutted building that night. He had been arrested before for setting fires; besides, they said, he was a Communist. It is quite possible, however, that the person mainly responsible for the fire was a man with unruly hair, burning eyes and a toothbrush mustache. The dictator of all dictators, his name was Adolf Hitler.

The confusion and hard times which Germany had suffered since its defeat in World War I provided an excellent opportunity for power-hungry dictators like Hitler. A few months before the Reichstag fire he had been named Germany’s Chancellor, or Prime Minister. Neither dictators like Hitler nor the Nazi Party which backed him had a firm grip on the government. (The name Nazi consists of the first four letters of the German word for “National,” in the name of the National Socialist Party.)

A new election was set for March 5. Something had to be done to assure the Nazis a clear majority in the new Reichstag. What better way than to create an incident which could be blamed on the Communists? This would frighten into silence the people who opposed dictators like Hitler. At any rate, whether Hitler plotted the Reichstag fire or not, the election so strengthened his position that the Reichstag passed a law giving him the powers of dictatorship. Hitler, now completely in control of the dictatorship, demanded blind obedience from the German people.

You will find that the ambitions of these dictators robbed peoples of the freedom and peace about which they had dreamed at the close of World War I. In fact, the policies of two of these dictators — Adolf Hitler in Germany and the Benito Mussolini in Italy — led to the outbreak of World War II. The story of troubled conditions from 1918 to 1939 will be told under the following heads:

1. In what ways did the world slip backward after World War I? Who were the dictators?

2. How did dictators like Mussolini affect rule in Italy?

3. How did dictators like Hitler bring the world ever closer to war?

4. Why did the democracies fail to meet the challenge of the dictators?

1. In What Ways did Dictators Slip the World Backward after World War 1?

For a few years after 1918 the peoples of the world had visions of a new era. Such hopes had their roots in important changes brought about by World War I and the peace settlements.

Republics replaced monarchies. World War I shook down kings’ crowns as a windstorm shakes ripe fruit from trees. First, Czar Nicholas II of Russia was forced to give up his throne. Then, in 1918, the war-weary people of Germany and Austria-Hungary revolted. Emperor Charles of Austria-Hungary fled to Switzerland, while Kaiser William II of Germany sought refuge in Holland. Within a few years other revolutions cost the rulers of Spain, Turkey and Greece their crowns. (Greece later turned back to monarchy, though the king’s powers were restricted.) Nearly all the European nations created by the peacemakers at Versailles-Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Czechoslovakia and the separate states of Austria and Hungary — became republics.

Countries where there had been representative government and where kings were merely symbols of unity (as in Great Britain or the Scandinavian countries) escaped violent change, but the really powerful rulers — the czars, kaisers, emperors and sultans — lost their thrones altogether and disappeared. Republics and representative government seemed to be gaining ground.

The war brought an end to the privileges of nobles. World War I did more than unseat kings. In most European countries the titles and privileges of the nobility were wiped out. The great estates which had been the real source of power of the nobility and big landowners disappeared. In Russia, these holdings were seized by the Communist government. In most parts of eastern Europe, laws were passed to break up estates into small farms. In Great Britain, taxes were so high that owners of large estates were glad to get rid of them. War, heavy taxation and inflation (lessening of the purchasing power of money) ruined many rich people and brought hardship to members of the middle class.

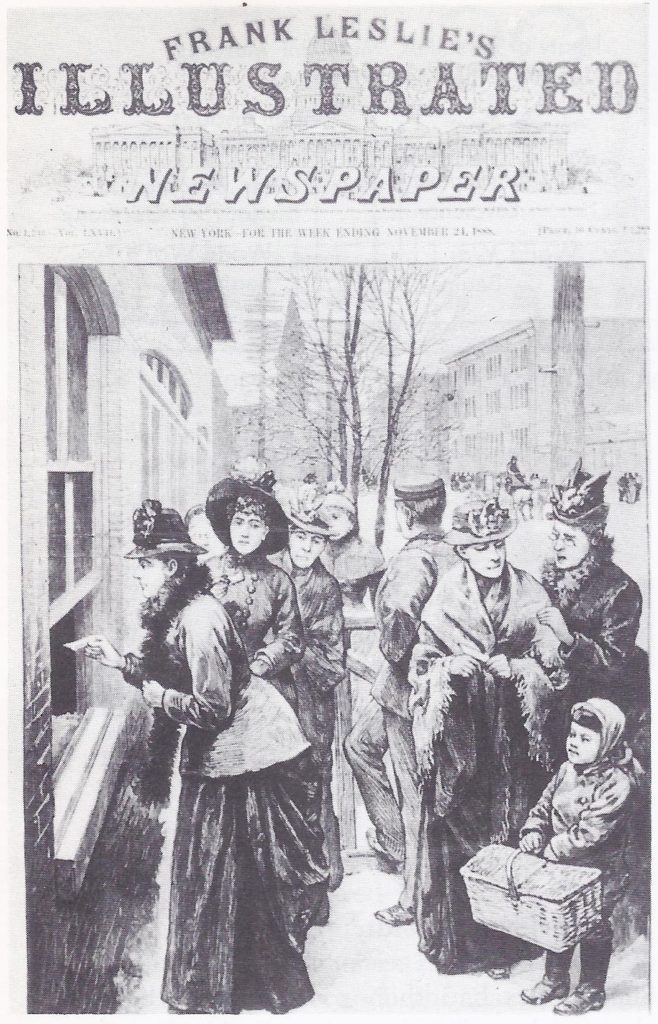

Women obtained equal rights. The constitutions of the newly established republics brought an end to privileges based on sex. So did new laws passed in some of the older countries. Before 1914, women were permitted to vote in only a very few nations of the world. Then during World War I, women made a great contribution to the winning of the war. They worked in factories to make arms and munitions and took the places of men in offices and stores. Since in service to their country and ability to do their part they were the equal of men, women felt they should have the same rights and responsibilities.

Soon after the war, women won the right to vote throughout the United States, most of Canada, Germany, Russia, Great Britain, Ireland, all Scandinavia, the Netherlands and the whole belt of new republics from Finland south to Czechoslovakia. Only in Switzerland and France, in parts of southern Europe and of Latin America and in Quebec (which granted suffrage to women in 1940) was the vote still limited to men.

Social life and customs changed more rapidly than at any time since the French Revolution, especially in the case of women. Women in China gave up the custom of binding their feet to keep them small. In Europe and North America women’s styles became more practical. Skirts no longer reached to the ground. Women began to bob their hair, drive cars and come and go, much as they pleased. In fact, the war relaxed social customs in many ways, not always desirable. Family ties were loosened and divorce became more frequent.

Many of the changes brought by World War I did not last. All these striking changes after World War I might have led a thoughtful person to observe: “The new ideas planted at the time of the French and American Revolutions grew rapidly in the nineteenth century and have now burst into full bloom. Absolute monarchs are no more. The great nobles have lost the privileges they used to possess. Liberal ideas and practices are on the march. Small national groups throughout Europe have won the right of self-government. Even the people of Asia and Africa, so long ruled by Europeans, are demanding the right to rule themselves. Everywhere old customs and ways of living are on the way out.”

Such conclusions might have made sense in 1920, but surprising changes took place during the next twenty years. With respect to individual rights and self-government, these were years when the hands of the clock were turned back. Dictators took over in fifteen European countries Italy, Spain, Portugal, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Greece, Turkey, Albania, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. Communist leaders ruled Russia with an iron hand.

What is dictatorship? Dictatorship places absolute power, unrestricted by law or constitution, in the hands of one person or a small group. Dictators may come into power by one of several routes — by an election, or by using the army to overthrow the existing government, or by persuading a king or president or lawmaking body to give him unusual powers.

Once in power, however, dictators depends on force alone. He does not govern because of an inherited “right” as a king does. Nor does he rule because he won his office in a free and open election, as a president does. He rules because of the airplanes, tanks and cannon he and his supporters control. Often millions of people are willing to have him rule. They have been taught to consider dictators a great patriot or ruler. They may care more about having peace and order and an opportunity to go quietly about their private affairs than they do about having self-government. Or they may be too fearful to rebel in the hope of depriving the dictators of their powers.

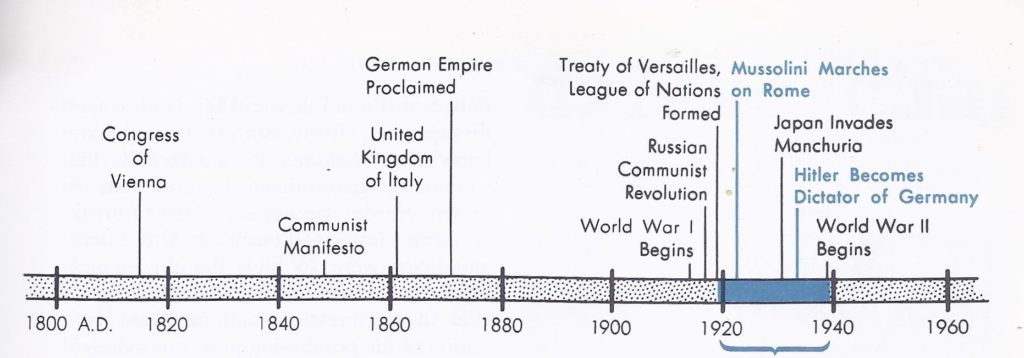

Modern European dictators were something new. Dictatorship itself was not a new thing in the world. There were dictators in ancient times; in fact dictators is a Latin word. You will remember one Roman dictatorship, Julius Caesar. Oliver Cromwell, as Lord Protector of England, exercised the powers of a dictatorship; so also did Napoleon during the years he was First Consul of France. In some parts of the world, such as Latin America, dictatorships have been common, but for a hundred years after Napoleon’s downfall, dictators were rare in Europe. Then a new crop of dictators arose between 1920 and 1940. These modern dictators possessed more powerful means of persuasion and control than the most ambitious despots of the past. Among these modern instruments of power were the radio, the motion picture, the tank and the airplane.

Upset conditions favoured the rise of dictators. Events might have been far different if the people of Europe had been prosperous and secure in the years between the two World Wars. Instead, between 1918 and 1939 Europeans suffered from poverty, unemployment, business depression and fear of another war. These conditions caused many a nation to seek safety in a strong leader, even if he had little regard for the liberties of the people.

Most of the trouble stemmed from World War I. Figures gave some idea of the losses in human life and property which Europe suffered in that war. In addition, the defeated Central Powers were saddled with huge war-damage bills and the Allies owed huge sums to the United States for loans made during the war. Widespread poverty in war-shaken Europe, in addition to the burden of heavy taxes, lessened people’s ability to buy. This condition caused unemployment. Some countries issued huge amounts of paper money, with the result that money dropped in value and prices went sky-high. Citizens lost confidence in the government’s promises to pay.

A drop in foreign trade made hard times even harder. Europeans had little or no money to invest in distant parts of the world. Europe had also lost much of its pre-war trade to the United States. Moreover, the creation of new states in Europe increased the number of customs barriers. Before the war, for example, there had been a single large free-trade area shared by all the peoples in the old Austro-Hungarian Empire. Now each of the new states created in the valley of the Danube by the peace settlements tried to become self-sufficient. Each put up tariff walls to keep out goods from other nations. So trade declined and people became less prosperous.

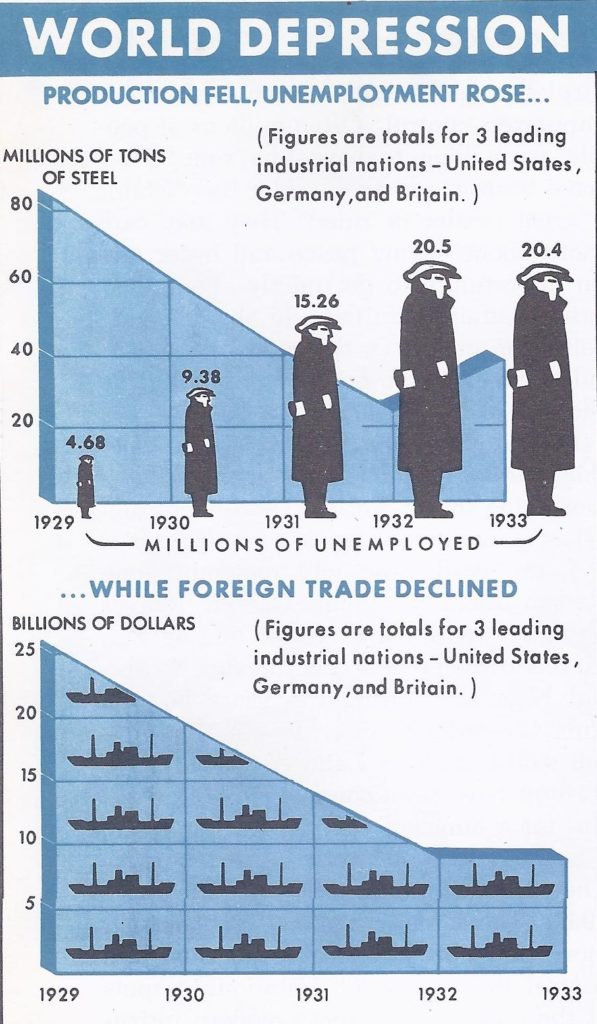

World depression made conditions worse. Though all Europe suffered poverty and hardship after the war, the severest blow did not fall until the 1930’s. There was even a slight improvement in conditions during the mid-1920’s, but a depression set in by 1929 and the situation worsened in October of that year when a panicky selling wave swept American stock exchanges. Prices of stocks, most of which had been far too high, collapsed, thereby bringing ruin to thousands of business concerns and millions of individual citizens. Trade declined, factories closed down and unemployment increased rapidly on both sides of the Atlantic. Panic developed in Europe when the state bank of Austria failed in 1931. Soon afterward, Great Britain was forced off the gold standard; that is, it no longer could redeem its bonds and paper money in gold. To relieve conditions, payments of war debts and reparations were suspended at the suggestion of President Herbert Hoover. They were never resumed.

During the 1980’s, while the depression was at its worst, important changes took place in Europe. Italy, already under a ruthless dictator, pursued a policy of aggression toward weaker nations. Other countries, notably Germany, became dictatorships. Spain had a revolution and a frightful civil war. Even those countries which suffered no violent changes in government faced serious economic and social problems. By the time economic conditions had improved somewhat, the stage was set for another world war. It is with the highlights of this tragic story that the remainder is concerned.

2. How did Dictators like Mussolini Affect Rule in Italy?

Italy was an unhappy victor. Italy supposedly was more fortunate than its former allies, Germany and Austria-Hungary, because it was on the winning side when World War I ended. Many Italians felt that the war had cost Italy more than had been gained. An Italian at the close of the war might well have said: “We have poured out more blood and treasure to gain southern Tyrol and a few coast towns on the Adriatic, than we did in all the wars for national liberty and union during the nineteenth century. Our allies begrudge us some of the territory we expected to acquire, such as the city of Fiume. Perhaps we would have done better to remain neutral. Perhaps a stronger government might have won for us richer spoils of victory.”

Conditions within Italy were indeed discouraging. Trade and industry were in bad shape. Strikes and riots among workers were common and Communist ideas were making headway among the poor. As in other European countries, there were many political parties, none of which was strong enough to remain in power for any length of time. One weak cabinet followed another and the government was unable to enact laws that dealt effectively with the growing problems of depression and unemployment. Under these conditions, many Italians longed for a “man on horseback” — a strong leader who would restore order and prosperity.

Under the dictatorship of Mussolini, a new Fascist Party gained control of Italy. The man who gave promise of being the strong leader so many Italians desired was Benito Mussolini. The son of a working man, Mussolini had become a Socialist and a newspaper writer before World War I. When the Socialist Party opposed Italy’s entrance into the war, Mussolini left it and served in the Italian army. After the fighting ceased, Mussolini organized bands of veterans called Fascisti, or Fascists. The Fascists wore black shirts and their emblem was the old Roman symbol of authority, the fasces or bundle of rods bound around an ax. The Fascists were a quarrelsome lot who often got into street fights with Italians holding other political ideas.

In 1922 the Fascists marched on Rome. The King and his ministers made no attempt to break up this parade of Mussolini’s black-shirted followers. In fact, King Victor Emmanuel III (the grandson of Victor Emmanuel) appointed Mussolini Prime Minister. For a few years the outward forms of constitutional government were kept. All real power, however, was in the hands of Il Duce, or “The Leader,” as Mussolini was called.

Soon the barrel-chested, square-jawed, loud-voiced Mussolini felt strong enough to do away with individual freedom and self-government altogether. He abolished all political parties except his own, the Fascist Party. From then on, Italy’s voters were presented, as were the Russian voters, with a single list of candidates for office. In Italy this list was prepared and approved by Fascist Party leaders. The voters, therefore, had no real choice.

Under dictator Mussolini’s Fascism, the state was absolute and all-powerful. Mussolini’s dictatorship centralized power in other ways. All local officials were chosen by the central Fascist government. Only ideas approved by the Fascist Party could be publicly expressed. Courts, schools, newspapers, radio and motion pictures were placed under government control and censorship. Both business firms and workers in various industries were organized into groups, or syndicates, under government control. Italy’s industrial, farming, labour and trade programs were all shaped to make the nation strong. In fact, though private ownership continued to exist under Fascist control, the government could, if it wished, disregard any private rights in the public interest. Dictators like Mussolini, in short, established totalitarian governments — a government which controlled all human activities. The liberty that Mazzini, Cavour and Garibaldi had planned and fought for in the mid-nineteenth century had vanished from Italy.

Within Italy, Mussolini’s dictatorship solved some vexing problems. Mussolini’s dictatorship succeeded in settling the long standing dispute between the Kingdom of Italy and the Pope. This dispute started when the Kingdom of Italy annexed Rome and the Pope became a voluntary prisoner in his own palace. Mussolini and the Pope reached an agreement in 1929. The Pope’s palace (the Vatican) and St. Peter’s Church became an independent state, the smallest in the world, named Vatican City.

The dictatorship also built roads, drained marshes and expanded industry. He spent huge sums on the army, navy and air force. The average Italian felt pride in these national achievements. He also earned more money, but he paid more for what he bought and taxes were higher. It may be doubted, then, that the average Italian was any better off for all Mussolini’s efforts and the individual’s freedom and importance had been lost.

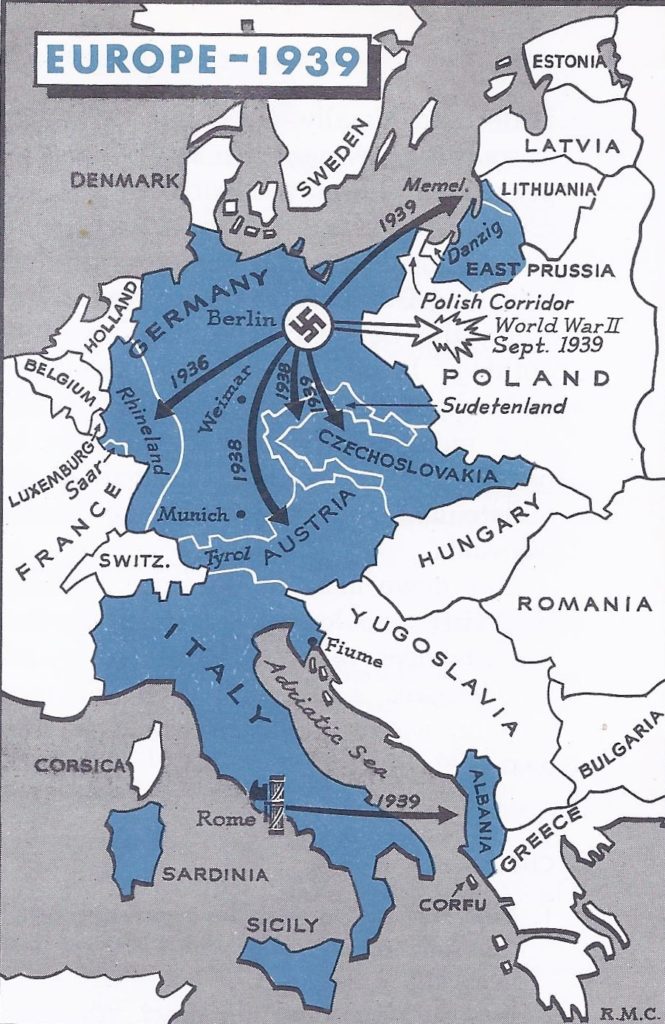

In world affairs Fascist Italy became a troublemaker. In relations with other countries Mussolini adopted a chip on-the-shoulder attitude. For example, he quarrelled with Greece when some Italian boundary commissioners were killed by bandits. To force Greece to pay damages, Mussolini seized the small Greek island of Corfu in 1923. Then the League of Nations stepped in and set up a special commission to arrange a settlement. In the end Greece paid damages and Italy gave back Corfu. For several years, too, relations between Italy and Yugoslavia were strained because of the border city of Fiume, which Italy took over in 1924.

It is the dictator Mussolini who led Italy toward war. His ambitions for land and glory still unsatisfied, Mussolini turned his attention to more distant lands. In the rugged highlands of eastern Africa is situated the independent country of Ethiopia, sometimes called Abyssinia. Once before, in 1896, Italy had tried to conquer Ethiopia but had failed. In 1935, confident that his army and air force would prove victorious, Mussolini picked a quarrel with Ethiopia.

The poorly armed Ethiopians stopped the Italian forces at first, but in the long run could not win. The Ethiopian Emperor, Haile Selassie, made an earnest but fruitless appeal to the League of Nations. The League condemned Mussolini’s attack on Ethiopia, but it took no effective steps to stop him. The more powerful League members would not co-operate. Mussolini’s answer was to take Italy out of the League of Nations and to give Italy’s king the added title of Emperor of Ethiopia.

The dictator Mussolini was still not content. To keep national pride at a high pitch and to take people’s attention off their problems and loss of freedom at home, he needed to continue his conquests. So in 1939 Mussolini invaded Albania, with which he had an alliance. He also sent soldiers to aid the Spanish dictator Franco in the civil war that raged in Spain. Finally, Mussolini plunged Italy into World War II on the side of Germany. This last step was to prove a fatal mistake.

3. How Did Dictators like Hitler Bring the World Ever Closer to War?

Defeated Germany formed a republic. Almost to the end of World War I the German people believed that their government and the German army would bring them victory. Defeat must have seemed to them like the end of the world. The German Empire crushed, the Kaiser in flight and Communists rioting in streets of Berlin! The bewildered people hardly knew which way to turn.

In the midst of defeat and despair a National Assembly met in 1919 in the city of Weimar, Germany, to draw up a constitution for a republic. This constitution provided for a president to be elected by the people for a term of seven years. There was to be a chancellor appointed by the president. This chancellor and his cabinet would be the leaders of the groups which could command a majority in the Reichstag, the lower house of the German legislature. Members of the Reichstag, who were to be elected by all the German voters, represented Germany as a whole. (An upper house represented the different German states.) Finally, the Weimar constitution permitted the president to dismiss the Reichstag in times of emergency. The first president was a Socialist named Friedrich Ebert.

The German republic faced difficulties from the start. Perhaps no government in Germany could have remained popular in the difficult days following the war. No matter how hard it tried, any government was bound to be linked in people’s minds with suffering and defeat. You should also remember that the German people were not used to self-government. Under the German Empire, most of the power had been centralized in the hands of the emperor and his chancellor. Now all was changed and the German people were supposed to control their own government. It was natural for them to make blunders, for self-government can be learned only by experience. Given time, the German people would have learned to govern themselves; but, like swimmers over their depth, they had no time.

One crisis followed another. So much paper money had been printed that it was nearly worthless. A man’s life savings, for example, would not buy a suit of clothes. Unemployment, hunger and despair haunted the German people. There were troubles also with neighbouring nations. A dispute broke out over the boundary between Germany and Poland. France tried to collect war damages by occupying the Ruhr valley, the industrial heart of Germany. Then President Ebert died. The German people, tired of politics and party politicians, chose Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg as president. Hindenburg was a dignified old gentleman who had defeated the Russians during World War 1. His election seemed to strengthen the republic, for the Germans felt more secure with one of their heroes as head of the government, but when world-wide depression brought more misery after 1929, people lost faith in the republic.

The republic had three enemies within Germany. There were, of course, many shades of opinion among German citizens, but three groups spearheaded the discontent with the German republic.

(1) There were the Communists who had been busy spreading their ideas and had converted a number of Germans to communism. Their solution for Germany’s troubles, as you would expect, was to set up a “dictatorship of the proletariat” in the Russian style.

(2) There were the German royalists who wanted to bring back pre-World War I days. These favoured a Germany dominated by a kaiser, the nobles, and the army.

(3) Dangerous though these first two groups were to the republic, it might still have survived. Royalist ideas did not appeal to the working classes, nor did Communist ideas attract the upper or middle classes or the farmers. It was a third group, the National Socialists, which in time destroyed the German republic. The National Socialists promised to solve all the problems of discontented people of all classes. Their leader was Adolf Hitler.

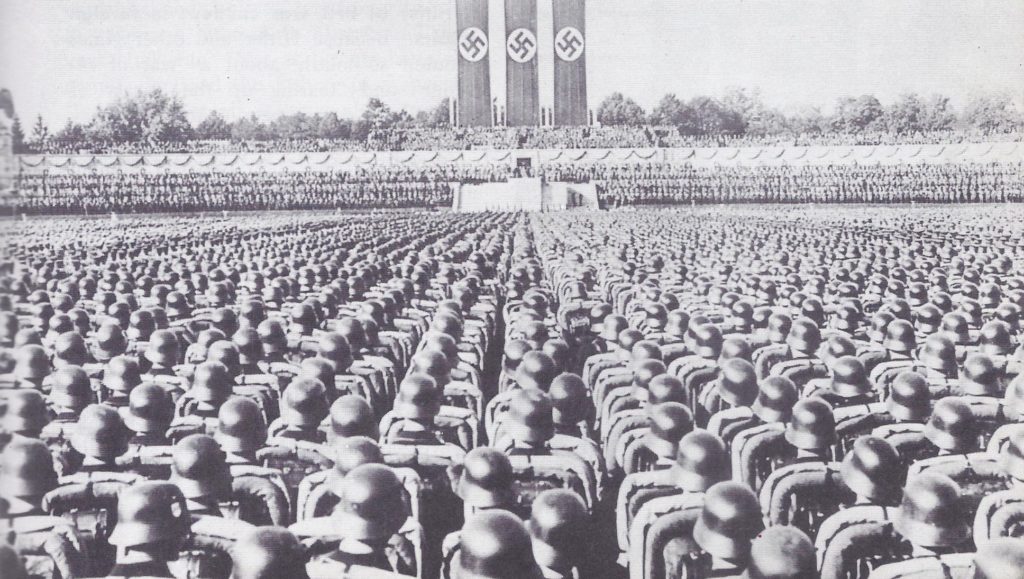

Hitler rose to power slowly. In contrast to Mussolini, Adolf Hitler climbed the ladder of power slowly. He was an Austrian who had served as a corporal in the German army in World War I. After the war, he organized bands of veterans much as Mussolini had done. Hitler’s followers were called National Socialists or Nazis. The Nazis wore brown shirts and their symbol was the hooked cross or swastika. Hitler promised to restore German power and prosperity.

During the 1920’s Hitler’s movement was scorned. He and his Nazis were regarded as a small group of extremists who knew nothing of practical politics. Hitler even spent a short time in prison for starting an unsuccessful uprising in the city of Munich. As times grew darker, however, the Nazis gained strength. In 1932 Hitler ran for the office of president. Though Hitler lost to Hindenburg, the Nazis controlled enough members in the Reichstag to block the passing of laws which they did not like. This was the first step toward control. Soon, Hitler became chancellor, gained control of the Reichstag and was proclaimed the Fuhrer, or Leader, of the German people.

Dictators like Hitler made themselves absolute ruler. Hitler lost no time in changing the German government from a democratic republic into one of the most absolute despotisms that the world has ever known.

All political parties except the National Socialist were abolished. German states became mere departments of the central government. Courts, schools, churches, newspapers, radio and motion pictures were all placed under Nazi Party control and the dictatorship.

The Nazis Dictatorship aimed to make Germany economically strong. Germany’s economic activities also came under strict Nazi control. Labour unions were abolished and in their place appeared a so-called “Labour Front” of drilled obedient workers. Strikes were forbidden. German industries also were organized under the Nazi government’s direction. All had to obey Hitler’s orders. German farmers were strictly supervised, too. The government forbade them to leave their farms for jobs in the towns and cities and fixed the prices of wheat, rye and certain other farm products.

The purpose of the Nazi program was to make Germany self-sufficient. The following words from a speech by Hitler in 1936 show this determination:

In four years Germany must be wholly independent of foreign countries in respect to all those materials which can in any way be produced through German capability, through our chemistry, machine and mining industries. . . . We hope thus to increase national production in many fields. . . . I have just issued necessary orders for carrying out this mighty German economic plan. Its execution will take place with National Socialist energy and force.

Moreover, dictators like Hitler were willing to go to any lengths to make their program work. For example, he believed that Germany’s farmers should have more land. As he expressed it, “It can certainly not be the intention of Heaven that one nation should have fifty times as much land as another. . . . We should be given the ground that is necessary for us to live on.” What the Fuhrer meant, of course, was that he would get land from other nations even if he had to seize it.

The Nazis Dictatorship allowed no opposition in Germany. The Nazi policies and programs taken together were called Germany’s “New Order.” The government poured forth a continuous stream of propaganda to convince the people of the New Order’s importance. Any who opposed it were sent to prison or to a concentration camp. There they stayed without trial until the Nazi bosses decided to let them out or killed them. Moreover, when members of Hitler’s Nazis themselves dared to differ with their Fuhrer, they were wiped out in a “blood purge,” just as Stalin had “liquidated” his opponents in the Communist Party in Russia. This reign of Nazi terror and tyranny Hitler called the “Third Reich,” meaning the Third German Empire. (The First Reich was the old Holy Roman Empire of the Middle Ages; the Second was the empire created by Bismarck in 1871.) This Third Reich, Hitler declared in the 1930’s, would last a thousand years or more. Actually, it lasted only twelve years and toppled into ruin at the close of World War II.

Hitler based the Nazi claim to supremacy on the idea that Germans were a superior race. In one important respect Hitler’s National Socialism differed from Mussolini’s Fascism. Dictators like Hitler made absurd claims. They insisted that the Germans were not merely a nation, like France or England or Italy, but a race. All Germany’s troubles, he said, stemmed from the fact that “pure” German blood had been mixed with other strains such as that of the Jews. So he took away German citizenship from all persons of Jewish descent. They could no longer vote, hold office, edit newspapers, or hold positions in business and the professions. They could not even marry “pure” Germans. Many Jews fled the country. Those who remained were subject to ill treatment and persecution. Then during World War II Hitler’s government decided to do away with them. Millions of Jews, along with other prisoners, were sent to concentration camps and systematically and brutally murdered.

There was, of course, no basis for Hitler’s notions of race. Scientific studies indicate that there is no such thing as a pure race, to say nothing of a superior race. Both the Germans and the Jews are of mixed ancestry, but the dictator and his party leaders found the Jews a convenient scapegoat on whom to lay the blame when anything went wrong.

Hitler had trouble with the churches. The Germans in general did not oppose the National Socialist program. They were proud to have a strong army again. Those who had been jobless welcomed the opportunity to work in the busy munitions factories. Many of them, of course, disliked the persecution of the Jews and the sending of innocent people to prison camps, but they dared not complain. Opposition might mean arrest by Hitler’s secret police and imprisonment or death for themselves and their families. Brave churchmen, however, did hold out heroically. Hundreds of priests and pastors, both Catholic and Protestant, lost their positions and risked their lives by refusing to obey some of the orders of the government.

What was Hitler’s secret? How, you may well ask, could this man, given to violent outbursts of temper, who had so little education or training, control the German nation completely from 1933 to 1945? No single answer can be given to this question. Undoubtedly his power sprang in part from his ruthless use of force. In part it resulted from the fact that he had made Germany once again a strong, united nation which European countries could not ignore. It stemmed also from his ability to hypnotize people by his words. An American reporter described the influence of the dictator’s speeches upon the German people in these words:

The man is truly a superb orator and in the atmosphere of the hand-picked Reichstag, with his six hundred or so sausage-necked, shaved-headed, brown-clad yes-men who rise and shout almost every time Hitler pauses for breath, I suppose he is convincing to the Germans who listen to him.

Hitler at first was cautious in foreign affairs. Hitler and other Nazis shouted so loudly about a “war of revenge” and “tearing up the Treaty of Versailles,” many people thought they would start war as soon as they were in office, but the dictator knew that the German army was not yet ready for action, so he proceeded slowly, one step at a time. (1) In 1933 he took Germany out of the League of Nations. (2) Two years later he made military training in Germany compulsory. (3) In 1936 Hitler marched German troops into the Rhineland, with its valuable coal and iron mines and its factories. According to the Treaty of Versailles, the Rhineland was to remain forever unfortified, but the dictator shrewdly timed his seizure of the Rhineland while Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia was on-going. By doing so, Hitler knew that other countries were unlikely to oppose his action. (4) Hitler and Mussolini came to an agreement which made them allies.

Hitler’s dictatorship expanded Germany’s borders by seizing free Austria. Encouraged by these successes, the dictator turned his attention to certain lands formerly a part of Austria-Hungary. The first of these was Austria, which had suffered badly since World War I and whose population spoke German. Here again, the Fuhrer moved slowly. He had refused to intervene when Austrian Nazis killed an anti-Nazi dictator and in 1935 he assured Austria that he would never interfere in its affairs. Hitler’s Nazi agents, however, were secretly at work in Austria stirring up trouble. When the Austrian government tried to check the activities of these agents, the dictator threatened and blustered. He demanded the release of the Nazis jailed in Austria. He even insisted that some of them be given positions in the Austrian government. Then, early in 1938, Hitler’s motorized troops rumbled into Austria. The Nazis took over and that was the end of free Austria for nearly twenty years. Of course, Hitler explained that he had acted only to protect German interests in Austria and prevent civil war. “Not as tyrants have we come,” declared the Fuhrer in a speech, “but as liberators” — the modern tyrants’ favourite word for themselves.

Hitler’s dictatorship took control of Czechoslovakia. The little republic of Czechoslovakia next received Hitler’s attention. Created at the end of World War I, it had become the most democratic country in central Europe. Among its peoples, chiefly in a district called Sudetenland, were about 3.5 million Germans. Hitler claimed that these Germans were being oppressed by the Czechoslovakian government. There was a noisy group of Nazi agents and their supporters in Czechoslovakia, just as there had been in Austria. These clamoured for the right to govern themselves, a demand the Czechoslovakian government refused.

Tension mounted. Great Britain and France were greatly worried. France was actually bound by an alliance to aid Czechoslovakia if that country should be attacked. The world stood very close to general war as Hitler shouted, “It (Sudetenland) is the last territorial claim which I have to make in Europe, but it is the claim from which I will not recede.”

In the end, dictators like Hitler got what they wanted. In September 1938 statesmen representing Great Britain and France met with Hitler and his ally, Mussolini, at Munich in southern Germany. In an effort to “appease” the Fuhrer, the British and French representatives agreed to a partition of Czechoslovakia. Surrounded on three sides by Germany and deserted by its allies, the helpless little state could do nothing. It had to surrender the Sudetenland. Within six months the world once more learned how dictators like Hitler kept their promises. He took over not only the Sudetenland but the whole of Czechoslovakia.

This move alarmed Europe. It meant that Hitler no longer pretended to limit his advances to areas inhabited mainly by Germans, but would grab any territory he wanted. Where would he turn next?

4. Why did Democracies Fail to Meet the Challenge of Dictators?

So far dictatorships were set up by the Communists in Russia, by the Fascists in Italy and by the Nazis in Germany, but the shadow of dictatorship was by no means limited to these three countries. Some, like Czechoslovakia and Austria and Albania, were swallowed up by their more powerful neighbours. Others, such as Portugal, Hungary and all the new Baltic states except Finland, had dictators of their own. Several Balkan states remained monarchies in name but were really dictatorships. What happened in two countries which became dictatorships — Spain and Poland — was to influence the turn of events for all Europe.

Spain suffered unrest after World War I. Although Spain had stayed out of World War I, it had many postwar problems. The government was corrupt and inefficient. Spanish peasants were poor, heavily taxed and uneducated. Large areas of land were held by wealthy landowners or by the Church. There were few businessmen or industrial workers in proportion to the population as a whole.

Matters went from bad to worse early in the 1920’s. The Spanish army had difficulty in crushing an uprising among the Moslem tribes in Spanish Morocco. The people of northeastern Spain demanded self-government. Some soldiers mutinied. The luckless King Alfonso kept his crown only by granting wide powers to a general, Primo de Rivera.

In 1930, however, the King forced Rivera from power. When elections were held, the people who favoured a republic won and Alfonso left the country. Next, a convention drafted a constitution providing for an elected president and a parliament (Cortes). Representatives elected to this Cortes closed church schools and broke up large landed estates.

In Spain, as elsewhere, the great depression increased poverty. When the government in power lost an election in 1933, its supporters called a general strike which led to violence. The new government, however, was strong enough to restore order.

Two opposing groups were struggling for power in Spain. The one (military leaders, Roman Catholic parties, monarchists and conservatives) wished to abolish the republic. The other (Socialists, Communists, members of trade unions), called the Popular Front, favoured the republic. Hoping to strengthen support for the republican government, President Zamora called a new election in 1936. The Popular Front won this election and ousted the President. Soon street fighting broke out between the two factions.

In the end, a group of army officers, headed by General Francisco Franco, staged a revolution of their own. “Scrap the new constitution,” they said, “and try Fascism instead.” They had troops to back them and a long, bloody civil war followed.

Dictators meddled in Spain’s civil war. Hitler and Mussolini wanted Franco to win and for important reasons. Under a powerful dictatorship Spain could help hold France in check and weaken Great Britain’s grip on Mediterranean sea lanes. Germany and Italy would then have a better opportunity to take what territory they wanted. So Hitler and Mussolini sent men and weapons to Spain to help Franco. On the other hand, the Russian dictatorship under Stalin felt that Spain was ripe for communism. So Stalin sent help to Spain’s “loyalists”– those who fought for the new Spanish constitution and government against Franco. Many volunteers from other countries also joined the ranks of the loyalists. The civil war raged for three years and at times threatened to become a general European war. In 1939 the loyalists were overcome and Franco became master of Spain. He “scrapped the new constitution” as he had promised and set up a Fascist government similar to Mussolini’s.

Poland’s life as a democracy was brief. Poland as well as Spain invited the attention of outside powers. The Poland created after World War I had an area larger than that of Italy and a population greater than that of Spain. On all sides Poland’s boundaries were in dispute with Germany in the west, with Czechoslovakia in the south, with Russia in the east and with Lithuania in the north. Inside this reborn country there were problems, too. Poland contained groups of Germans, Lithuanians, White Russians and Ukrainians, each anxious to be free from Polish rule. This made real unity impossible. Widespread poverty added to Poland’s difficulties.

With all these troubles, it is small wonder that Poland’s democratic government gave way to military dictatorship. In 1926 a hero of World War I, quick-tempered, patriotic Marshal Joseph Pilsudski, overthrew the government and set up a dictatorship. After Pilsudski’s death in 1935, Poland remained halfway between constitutional government and dictatorship. Outwardly Poland was a republic, but the real power was in the hands of a small group of army officers.

Nazi Germany Dictatorship threatened Poland. As Hitler’s program for expanding German power unfolded, Poland’s position became critical. Trouble might develop over the German-Polish boundary. Or it might break out over the Polish Corridor which connected Poland with the Baltic but separated East Prussia from the rest of Germany. Hitler greedily eyed the Polish Corridor and the free city of Danzig in spite of the fact that Germany and Poland had signed an agreement not to attack each other. Encouraged by the fact that other European powers had not seriously opposed him in the Rhineland, Austria, or Czechoslovakia, Hitler broke his treaty with Poland in 1939. Later in the same year he reached an agreement with Stalin, who wished to share in the partition of Poland. The way was now paved for Hitler to send his troops into Poland. Nervously Europe’s statesmen eyed Hitler, wondering when his war machine would start rolling.

Democracy still existed in many countries. What, you may well ask, was happening elsewhere in Europe? Had democracy disappeared? If not, why didn’t the democratic states take action to halt the dictators who threatened the peace?

None of the countries which became dictatorships had been real democracies before World War I. In those countries where democracy had been firmly grounded, it continued. Among the democratic states were the Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Norway and Sweden), Belgium, Holland, Switzerland, France and Great Britain. True, most of these countries were monarchies in name, but the kings had little to say about public policy. Actual power in such countries was in the hands of ministers who represented the majority in parliament and members of parliament were elected by the voters.

Of the countries just named, France and Great Britain had borne the brunt of the fighting for the four long years of World War I. Though they were victors in that conflict, they found victory very costly. Postwar problems put a severe strain upon them.

France found recovery difficult after World War I. The French statesman Clemenceau, who had led France to victory in World War I and had helped to make the peace of Versailles, wrote a book. Its title in English was The Glories and Miseries of Victory. This title aptly describes the condition in which France found itself between the two World Wars. The French had many reasons for being proud and happy. They had fought heroically during the long conflict. They had regained their lost provinces of Alsace and Lorraine. They had added Syria and parts of Africa to their overseas empire and they had taken the place of the defeated Germans as the leading nation on the continent of Europe.

There was a heavy price for all these gains. During the war France had suffered a terrible loss of man power as well as great destruction of property. Most of the trench warfare on the western front had been fought in French territory. As a result, French towns and villages, mines and factories had been destroyed. The Germans had not met their payments for war damages, French taxpayers had to dig into their own pockets to pay most of the cost of rebuilding. French paper money declined in value and the depression of the 1930’s brought unemployment, political scandals, street riots and ugly rumours of plots against the French republic.

There were problems also in the field of foreign affairs. Some French statesmen wanted to make friends with defeated Germany; others were opposed. Under Mussolini, Italy became France’s jealous rival. When Hitler began to build up the German army, navy and air force, France’s position as leader of Europe declined and the French began once more to fear Germany. Beset by problems at home and abroad, France turned from one political leader to another. French cabinets were unable to remain in power for any length of time.

Britain, like France, faced difficult problems. During World War I the British Empire had held together well. Victory had brought new territory — parts of Africa, some of the former German islands in the Pacific and League of Nations “mandates” in Palestine and Iraq. Between the two World Wars, the British Empire went through striking changes. It became the Commonwealth of Nations as the Dominions became practically independent. Ireland went its own way, apart from the Commonwealth. India gained a greater measure of self-government. Despite these far-reaching changes, the overseas Commonwealth nations remained loyal to the mother country. When Great Britain entered World War II, they rallied to its support.

Nevertheless Britain faced serious problems following World War I. The British had not suffered as much destruction of industries, farms and houses as had the French, but British finances were severely strained. After World War I, Englishmen were burdened with heavy taxes. What pinched them even more was their loss of foreign trade. The British, as you know, depend heavily on commerce. Some of the nations with which they had traded before the war had come to depend on other nations to supply their needs. Some had suffered too much from the war to be good customers. With dwindling markets in other lands, English factories could not sell their output. Hard times and unemployment plagued Great Britain. Many workers “went on the dole,” that is, received public unemployment relief.

The British Labour Party came into power. Before World War I, the two major political parties in Great Britain had been the Conservative and the Liberal. The Labour Party, composed largely of members of trade unions, was a much smaller group. When hard times hit Great Britain, the Labour Party gained strength. On two occasions its leader, Ramsay MacDonald, served as Prime Minister, but the Conservatives held control of the government during most of the 1920’s and 1930’s.

The democracies hesitated to cross swords with the dictators. In short, between 1920 and 1939 the nations of Europe, great and small, were deeply concerned with problems of their own. All were struggling with hard times at home and hard times meant trouble for the governments in power.

Democracies like France and Great Britain wanted to preserve peace. They joined together in agreements to scale down armies and navies and by so doing eventually found themselves weaker than the dictatorships. The democracies signed treaties to outlaw war. They supported the League of Nations, but they were not willing to risk war to halt aggression. When Mussolini struck at Ethiopia and when Japan attacked Manchuria, the democracies merely condemned these gangster tactics with words. When Hitler moved against Czechoslovakia, they weakly agreed at Munich to the partition of that nation. No wonder the dictators felt that they could act without fear of opposition! Not until Hitler attacked Poland in 1939 did the governments of Great Britain and France oppose force with force.

TIMETABLE — DICTATORS DESTROY WORLD PEACE

Japan seized Manchuria from China, 1931 – 1932 .

Germany comes under the dictatorship of Hitler, 1933

Fascist Italy conquered Ethiopia, 1935 – 1936

Italy, Germany and Russia intervened in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939

Japan invaded China, 1937

Nazi Germany annexed Austria, March, 1938

Germany took the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia, September, 1938

German troops occupied rest of Czechoslovakia, March, 1939

Italy occupied Albania, April, 1939

Germany invaded Poland and started World War II, September, 1939