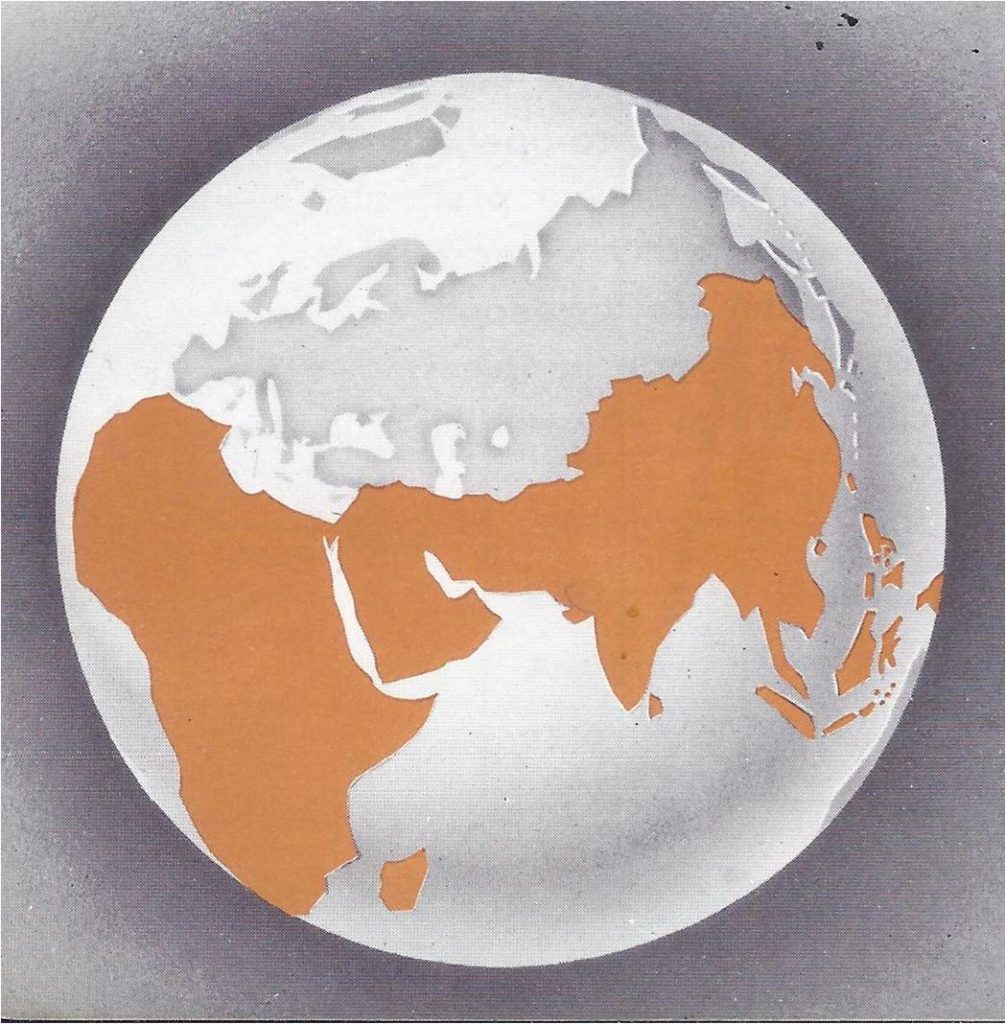

Nationalist beliefs in Asia and Africa swept over changes in many lands. In the spring of 1955, the city of Bandung, Indonesia, was tense with excitement. Crowds lined the streets to catch glimpses of delegates attending an international conference. The citizens of Bandung saw Arab diplomats arrive, dressed in the flowing robes and headdress of the desert. They saw prime ministers and foreign ministers wearing the jaunty caps and spotless white clothing popular in tropical South Asia. The rest of the world watched too, for the Bandung Conference was the first of its kind ever to be held. Only Asian and African statesmen were present, yet they spoke for half of the world’s people. Many of the 29 nations they represented had become independent since World War II. In short, the Bandung Conference was a symbol of the tremendous changes that swept across Asia and Africa after 1945.

We read about the recent nationalistic efforts of Asian and African peoples to gain freedom from colonial control, to run their own affairs and to achieve a better standard of living. This nationalist awakening made India a free nation. It brought important nationalistic changes in Southeast Asia. It set the Moslem Middle East aflame with nationalist feeling and swept over Africa. The Communist drive to gain power round the world, but nationalist events in Asia and Africa are important to free people everywhere.

- What nationalist changes took place in China and Japan since world war 2?

- How has nationalist beliefs affected India and Southeast Asia?

- How did nationalists changed the Moslem world?

- How has the desire for freedom transformed nationalistic Africa?

1. What Nationalist changes have taken place in Japan and China since World War 2?

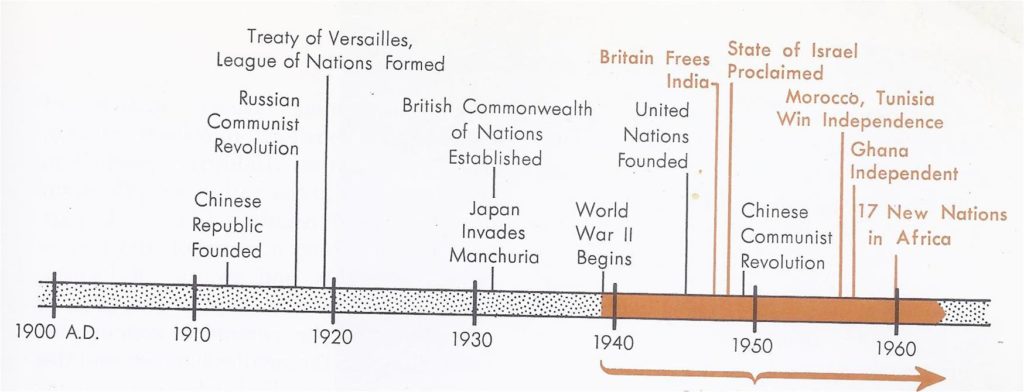

Before World War II, much of Asia’s history centred about China and Japan. Huge in area and population, China had the longest continuous past of the world’s nations. In comparison, Japan had at one time seemed insignificant. By adopting modern methods, Japan made itself the most powerful nation in the East. The Japanese embarked on a program of empire-building, chiefly at the expense of their larger neighbour. For China, World War II began with the Japanese invasion of 1937.

New forces engulf Asia. During World War II, Japan conquered not only much of China but also the Philippines, French Indo-China, British Malaya, the Dutch East Indies and countless islands of the South Pacific. At the war’s close, however, Japan had lost all of its territory except the home islands, and these were occupied by Allied forces.

Japan’s complete defeat left the conquered regions in chaos. During the war, China had become weakened and divided, while the Western powers had lost their colonies in Southeast Asia. These developments had important consequences: (1) A surge of nationalist beliefs swept over lands which for years had been colonial possessions. (2) The confusion in China and Southeast Asia enabled the Communists to extend their power.

China was a great power in name only. In 1945 China officially was one of the Big Five, ranking with the United States, Britain, France and Soviet Russia. China held one of the Five permanent seats in the UN Security Council. With more than a half billion people, vast resources and a long-established civilization, China had the potential to become a great power. However, as the great Chinese thinker Confucius had put it centuries before, “The requirements of government are sufficiency of food, sufficiency of military equipment and the confidence of the people in their ruler.” None of these three conditions existed in China at the close of World War 2.

The strongest group in China was the Nationalist Party headed by Chiang Kaishek. When Japan invaded Manchuria, the Nationalists rallied the people against the invaders and Chiang was hailed as a hero. Then, when the Japanese invaded China proper, the Nationalist government was forced to move inland. Millions of soldiers, workers and students joined in the resistance movement against the Japanese. Separated from many of its supporters in the coastal provinces, the Nationalist government came to rely on the large landlords in the interior for support. Changes in the seat of government, an uprooted population and the uncertainties of war made elections impossible. Officials remained long in office and many of them became tyrannical and corrupt. The long-suffering peasants, disappointed by unfulfilled promises of reform, lost confidence in what seemed to them an increasingly less effective government.

The Communists won control of China. The Chinese Communists made the most of Chiang’s weakness and the upheaval caused by the war. When the Nationalist government moved westward, the Communists stayed behind. They waged guerrilla war against the Japanese and promised to carry out reforms when they came to power. With the defeat of Japan, full-scale civil war once more broke out. The Communists under Mao Tse-tung were strongest in northern China, where they received military aid from Russia. China’s Communist leaders found it easy to recruit followers among the half-starved, restless Chinese peasants.

Between 1945 and 1949 the Communist armies became masters of nearly the whole of China. Mao’s “People’s Government” replaced the Nationalist government and General Chiang Kai-shek and his half-million Nationalist troops withdrew to the island of Formosa (Taiwan). In 1950 Communist China signed an alliance with Soviet Russia.

Red China’s program of industrialization was only partially successful. Red China’s leaders, with Soviet aid, set out to transform the country into a modern industrial nation. Their program required workers to build roads and dams and to fill jobs in industry. To feed a growing number of industrial workers, it became necessary for fewer farmers to produce more food. Hence, millions of peasants were assigned to collective farms, called communes. Industrial production increased, but in the early 1960’s the farm program ran into serious trouble. In part this resulted from a series of disasters — floods, droughts and swarms of locusts. Mismanagement as well as peasant opposition to the commune system also contributed to the smaller harvests and the resulting famine. Red China was compelled to spend hundreds of millions of dollars in purchasing grain from Canada and Australia. Thus, funds which the Communists had hoped to use for machines and raw materials were spent for food.

Defeat did not bring collapse to Japan. No war-like nation ever fell from the heights of empire more swiftly than Japan. By its defeat, Japan lost its hold on China and Southeast Asia. Sakhalin was handed over to Soviet Russia, Fermosa and Manchuria to China. Korea, though declared independent, was occupied in the north by Russian troops, in the south by Americans. The United States became trustee over many small Pacific islands formerly held by the Japanese.

One may ask why defeat did not bring a similar fate to Japan as China had suffered. Three factors were responsible — Japan’s island position, the adaptability of its people and military occupation by the United States.

Sweeping changes took place in Japan during the occupation. After its surrender, Japan was governed by the Supreme Command of the Allied Powers. General Douglas MacArthur was the first Supreme Commander and nearly all of the occupation troops were American. The purposes of the occupation were (1) to disarm Japan and (2) to make it impossible for that country to wage another aggressive war. Gradually a third goal emerged — to encourage the Japanese to adopt democratic government and institutions.

For decades the Japanese had adopted certain Western ways of doing things, especially in industry and the military impressed with the strength of the Western democracies, the Japanese now made further changes in their way of life. Under a democratic constitution adopted in 1946, the emperor lost his absolute authority and no longer was worshiped as a god. (Many Japanese feel that this constitution was imposed on them, the question of a new constitution was later raised). Universal suffrage, the secret ballot and the right of workers to collective bargaining were guaranteed. This constitution also abolished the army and the navy stating that war would never be used to achieve foreign policy goals. Changes in school programs, the opening-up of educational opportunities to women and their participation in politics, business and industry were other revolutionary changes.

The occupation of Japan ended in 1952. In September, 1951, Japan signed a peace treaty at San Francisco with 48 Allied nations. (The Soviet Union and two satellite countries, though present, refused to sign this treaty.) In the following April, when the peace treaty went into effect, the Allied occupation of Japan came to an end. The United States, however, retained air bases in Japan under the terms of a security treaty. Although Japan has developed a Nationalist Safety Force for defense purposes, the Japanese have shown no interest in becoming a military power.

Japanese industry and commerce have expanded. Despite American spending, Japan’s economic recovery was slow during the years just after the war. With the outbreak of fighting in Korea, war orders caused Japanese industry to boom. Increasingly Japan becomes a competitor of the Western industrial nations in the markets of the world. Since 1956, Japan has used atomic energy in producing electricity and today co-operates with the United States and Britain in the development of peaceful uses of atomic power.

During the early 1960’s Japanese imports increased more rapidly than its exports. To improve its financial position, Japan has encouraged tourist travel and has set a goal of more than doubling its exports to the United States by 1966. Japan has agreed to lift import restrictions on American manufacturers and to repay American loans of about 500 million dollars made during the occupation period. The quality and amount of Japanese industrial production, as well as the level of wages paid to labour, were far higher than world war 2.

2. How Did Nationalist Beliefs Affect India and Southeast Asia?

Indian leaders worked for independence before World War II. In the subcontinent of India, there was a growing and insistent demand for independence. The British control over India had been established in the late 1700’s. British troops maintained order and protected India from outside attack. British businessmen established some factories and mills in India. Britain not only introduced certain reforms but also granted the Indians greater responsibility for their own government. An important step in this direction was the new constitution in 1935.

Many Indians, however, were far from satisfied. They felt that India’s natural resources and industries were enriching foreign investors. They objected to the new constitution because it left control of defense and foreign affairs in the hands of the British Viceroy. In brief, only independence would satisfy India’s nationalists.

World War 2 opened the way to Indian independence. Then came world war II and with it the threat of Japanese invasion. In this crisis Britain offered India control of its own affairs, but there were conditions to the British offer: (1) India was to wait for home rule until the war was over; (2) India meanwhile should work out a plan of self-government acceptable not only to its many separate states but also to both Moslems and Hindus. The British offer failed to satisfy some of India’s leaders. They argued that the Indians could both govern themselves and defend India from the Japanese. When these Indians continued to oppose British rule, many of them, including Nehru and Gandhi, were imprisoned.

The Dominions of India and Pakistan were created. After World War II ended, the British government was prepared to keep its promise of independence. The long-standing differences between Hindus and Moslems posed a difficult problem.

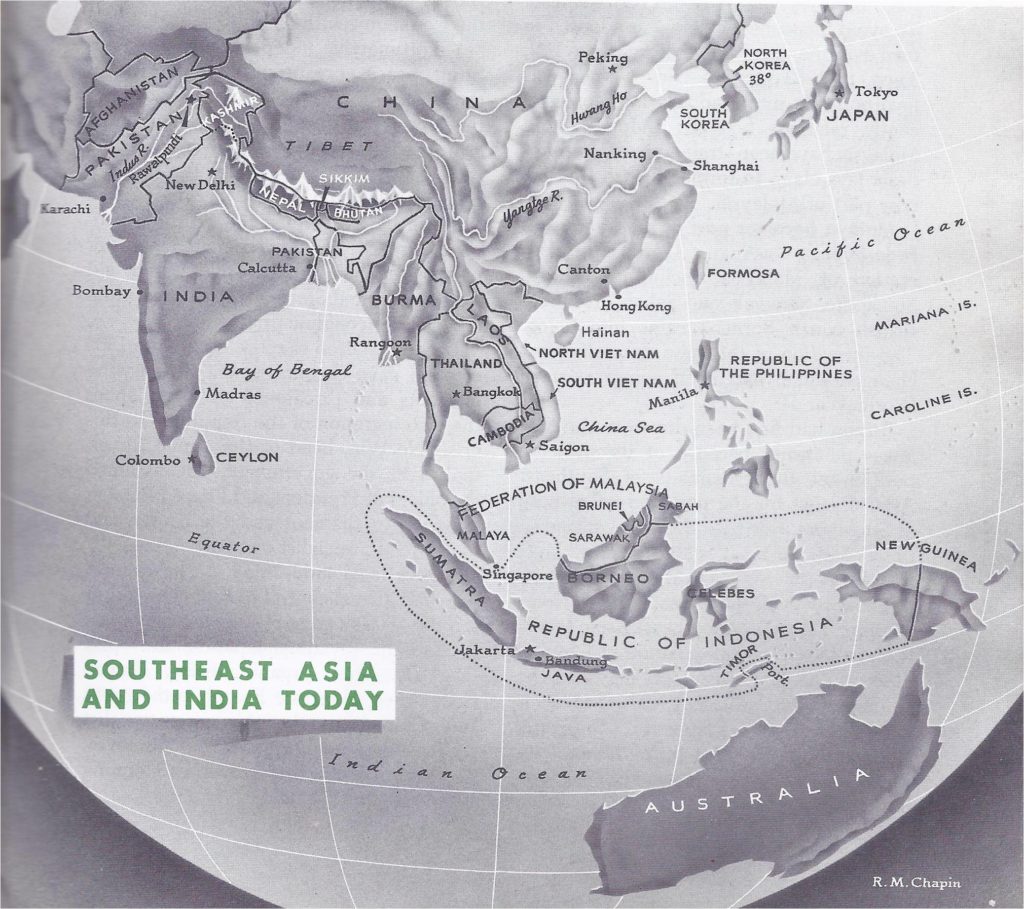

The 70 to 80 million Moslems were convinced that their rights would not be respected under a government controlled by Hindus. As a result, not one but two Dominions of the British Commonwealth were created in 1947. The larger, called India, included the regions where the great majority of the people were Hindus. Pakistan, the other Dominion, included the portions where Moslems outnumbered Hindus: (1) the Indus River valley in the west and (2) territory far to the east on the Bay of Bengal. Eastern and western Pakistan were separated, therefore, by a thousand miles of Indian territory. India and Pakistan were to govern themselves and manage their own foreign affairs.

India and Pakistan stayed within the Commonwealth of Nations. Indian independence marked another important step in Britain’s policy of gradually loosening control over its possessions. In 1948, the island of Ceylon became another self-governing Dominion. Then, in 1950 India became officially the Republic of India and six years later Pakistan proclaimed itself a republic. India and Pakistan both retain a link with the Commonwealth. They regard Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II as a symbol of their association with the other members of the Commonwealth.

The Republic of India set up a new government. When India became a republic, it adopted a new constitution patterned in some respects on America’s own. The Indian constitution contained a Bill of Rights. It joined the several states of India in a federal union. It set up a representative democracy with an elected president and a legislature of two houses. The new constitution also borrowed from the British plan of government. India, like Britain, has responsible government. The Cabinet, headed by the Prime Minister, stays in power so long as its program has the support of the lower house. After the Republic of India held its first election, Nehru became Prime Minister.

The division into India and Pakistan caused tragedy. The creation of separate Dominions of Pakistan and India left many Hindus in Pakistan and many Moslems in India; the age-old hatreds between the two groups led to violence. Thousands were killed in riots and millions fled across the new borders to escape from areas where they no longer felt welcome. In 1948 the revered Hindu leader Gandhi was assassinated by a fanatic who opposed the formation of Pakistan.

Relations between India and Pakistan remained troubled. Tension continued between the republics of Pakistan and India. One of the chief differences concerned Kashmir. If you look at the map, you will see that Kashmir borders on both India and Pakistan. Both India and Pakistan claim Kashmir. Although the two countries agreed in 1953 to let the people of Kashmir decide whether to join India or Pakistan, no plebiscite has yet been held. Kashmir remains a source of irritation between the two rivals and outbreaks of violence continue to drive refugees from one country to the other.

Adjusting to new ways of living proved difficult. The task of transforming India into a modern democratic nation has not been easy. Its constitution promised justice and equality to all people regardless of race, colour, or class. Thus the ancient caste system was to be abolished and all men and women were to become voters. The mere passing of laws is no guarantee that they will be carried out. For centuries Hindus had observed the rigid rules of the caste system and treated with contempt the unfortunate “untouchables.” To wipe out such discrimination in a hurry was difficult.

To the people of India, moreover, complete self-government was a new experience. Time would be needed to extend education to the impoverished millions. Nevertheless, a remarkable start was made. In India’s first nationalist election, held in 1951-52, 60 percent of the eligible voters cast their ballots (a bigger turnout than in many American elections).

India has sought a higher standard of living. When India became independent, it faced serious economic problems. Three-fourths of the people were farmers, but because of inefficient farming methods and a limited amount of fertile land with sufficient rainfall, India could not produce enough food for its people. Nor did India have the necessary power and industry to meet the country’s needs. Yet large quantities of manufactured goods could not be imported so long as India had to buy food abroad for its undernourished millions.

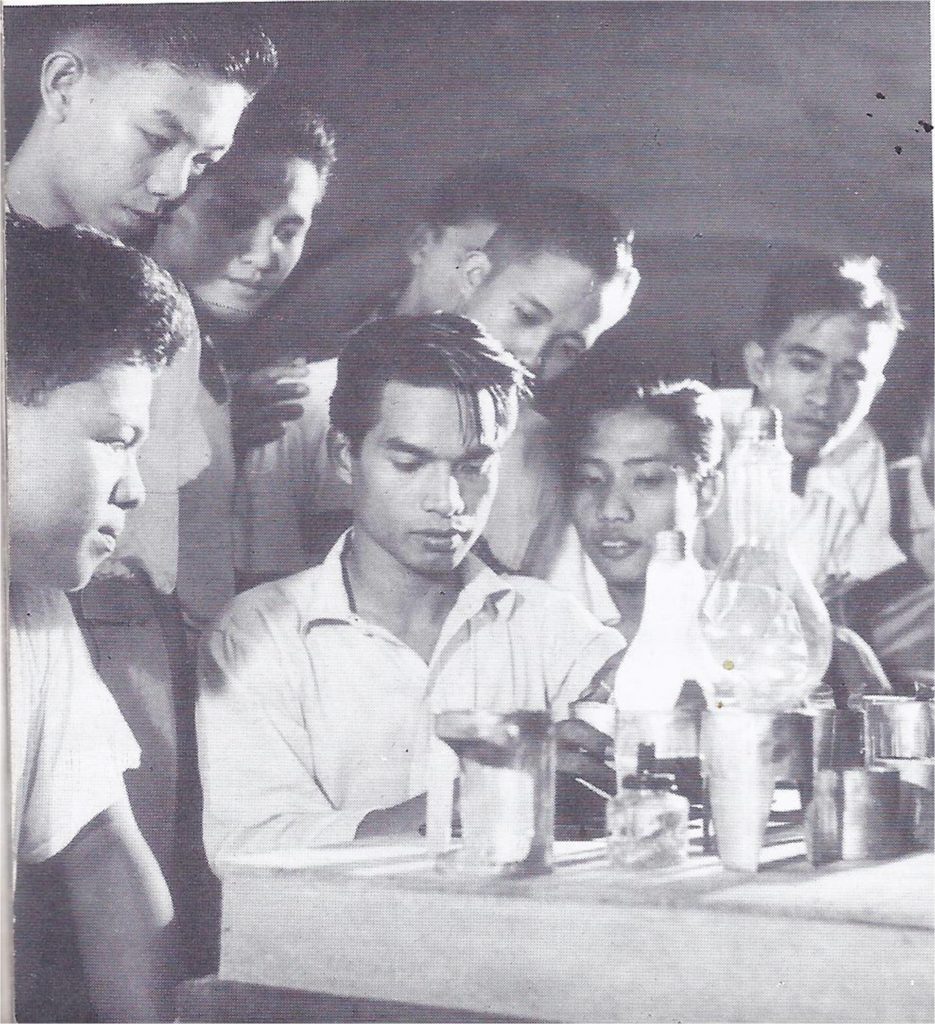

The Indian government took steps to overcome these handicaps. India’s school system steadily expanding. By 1960, India had 40 universities, 44 research institutions and about 1550 colleges. Since 1951 the Indian government has launched a series of Five Year Plans to increase farm and industrial output and to improve health and education. The third Five Year Plan (1961-62 to 1965-66) set as its goal an increase in agricultural production to make India self-sufficient in grains. Reforms to help farmers acquire land were also under way.

Both India and Pakistan received outside aid to help them develop modern industry and agriculture. In 1950 the Colombo Plan called on members of the British Commonwealth to contribute 5 billion dollars to help develop South and Southeast Asia. The United States has contributed massive economic aid and has sent experts to both India and Pakistan. Soviet Russia also loaned India money and provided machinery and engineers.

Roads, rivers and canals are being improved and thousands of miles of new railroads have been built. Several huge dams are under construction to provide water for irrigation and to generate electricity. Between 1951 and 1961 the power generated from all sources had been increased nearly threefold. Military production made necessary by a frontier dispute with China slowed progress and strained India’s resources.

Despite progress many problems remain. India’s gains are encouraging but the nation’s needs remained staggering in size. Industry had a long way to go in this country where 300 million people still tried to live off the land. Any gains in food production were offset by India’s population increase of about two per cent per year. Severe economic restrictions placed on Indians in Burma and Ceylon have led to an influx of impoverished refugees into India. India’s rapidly increasing millions needed more knowledge and material aid if they were to live better.

India took an independent stand in international affairs. Although India’s progress depends on help from others, the country has remained outside of the free world’s alliance systems. India’s leaders have favoured neutrality, feeling that their new country could not afford to become involved in war. For this reason, India for a time was reluctant to accept United States military aid. Indian leaders viewed American moves to halt the spread of communism as part of a power struggle which threatened world peace. We should remember that throughout the movement for independence, Gandhi stressed: the doctrine of non-violence.

India’s policy of neutrality troubled the American government when Communists threatened to take over Southeast Asia. On its part, India was disturbed by American military aid to Pakistan. The purpose of this aid was to contain Communist expansion, but Indians believed a well-armed Pakistan to be a threat to India.

Chinese aggression aroused India to the threat of Communist imperialism. India’s neutralism was badly jolted by Red China in the early 1960’s. China had not accepted the frontier line claimed by the British when India was a British possession. Despite the fact that Red China and India were friendly, Chinese troops in 1962 began to penetrate “disputed” border territory both in the northeast and the northwest. Although Indian troops were unable to resist this advance, the Chinese toward the end of the year announced a cease-fire. Meanwhile, Nehru requested arms and airplanes from Britain and the United States. An unfortunate by-product of American military aid to India was the reaction in Pakistan. Convinced that a stronger India would be a threat to its security, Pakistan became friendlier with Communist China.

American leaders understood the important role that democratic India played in Asia and recognized the need to help that country strengthen its economy. Despite the death in 1964 of Prime Minister Nehru, the United States’ relations with India remain unchanged.

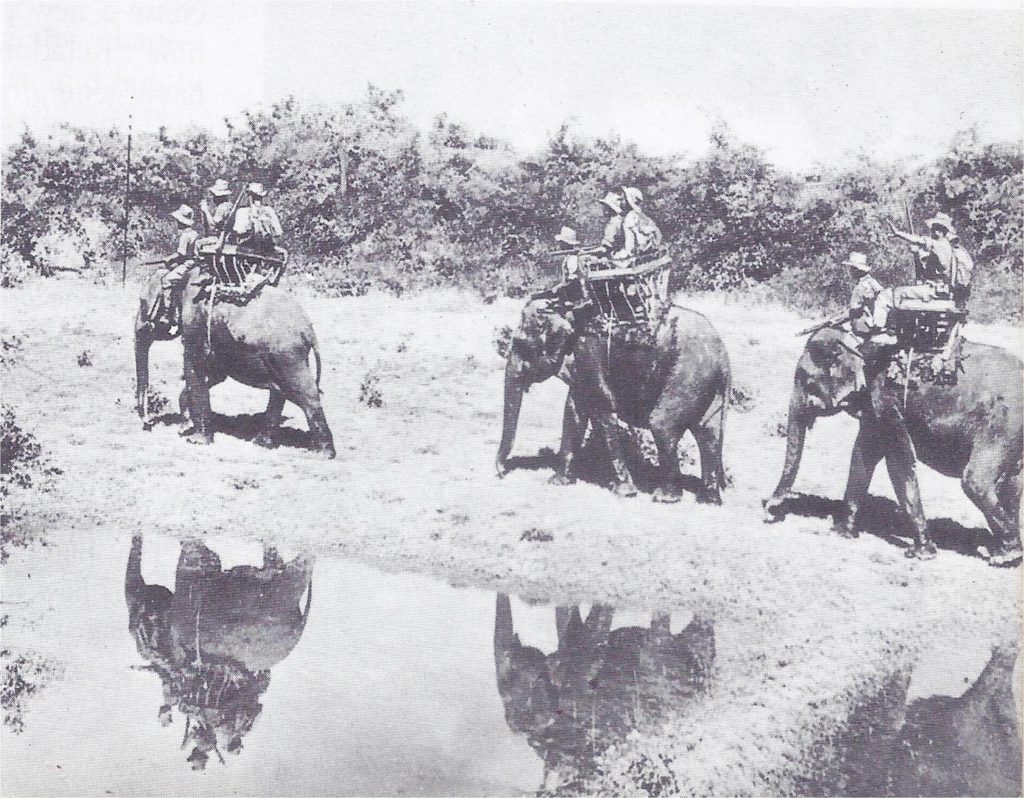

World War II creates unrest in Southeast Asia. Southeast Asia was another region seriously affected by World War II. During the war the conquering Japanese imposed harsh military rule on the peoples of this area. Some of the countries affected lay on the Asiatic mainland (Burma, Malaya, Thailand, Indo-China); others were groups of islands such as the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) and the Philippines.

During the 1800’s and early 1900’s, Europeans had sought to skim off the resources and wealth of Southeast Asia as they did in other parts of the world. They increased the production of such products as coffee, rubber, tin; and controlled the rich trade of their new colonies. Here and there a few bold Southeast Asians, educated in Western countries, spoke out against European domination, but most of the people continued to live in their villages much as they had for centuries. Then came World War II and the Japanese conquest. Though unhappy under Japanese rule, the peoples of Southeast Asia were impressed by the crushing defeat of their European masters by an Asian power.

The peoples of Southeast Asia sought independence. Following the end of the war, Southeast Asians were unwilling once again to become European colonies, but the road to independence was filled with problems. During the war guerrilla armies had sprung up to fight the Japanese. Later these guerrillas fought the returning forces of the colonial powers. It was hard to restore order with armed bands roaming the countryside. Moreover, war had brought destruction and loss of trade, leaving millions of people poverty-stricken.

The unsettled conditions were made worse by the activities of Communist groups. Wherever people are poor and hungry, resentful of outside control, Communists take advantage of the situation. Southeast Asia therefore became a fruitful field for Communist activity.

Continued unrest in Southeast Asia has more than once threatened world peace. Let us look at developments since World War II in some of these lands.

Indonesia wins independence and adopts an aggressive foreign policy. The Republic of Indonesia, which gained independence in 1949, includes over 3000 islands stretching in a line some 3000 miles along the equator. Rich in rubber, coffee, tea, spices, oil, tin and other minerals, the East Indies (as they were formerly called) attracted eager European traders. These islands became part of the Dutch colonial empire and were captured by Japanese forces during World War 2. When the war was over, the Indonesians resisted the efforts of the Dutch to regain control.

One of the new republic’s problems holding its sprawling territory together. Over half of the 100 million Indonesians are crowded into the island of Java. In much larger Sumatra, many Indonesians came to resent the inexperienced government centred in Java. There were frequent uprisings in the “outer islands.” Conflict and turmoil provided an opportunity for the Communists to gain strength among the discontented people.

Indonesia’s ties with the West were weakened by a long dispute with the Netherlands over western New Guinea. Indonesia claimed this half of the island, but the Dutch remained in control. Angry at what it called “Dutch imperialism,” the Indonesian government in 1960 broke off relations with the Netherlands.

In 1962 Indonesian guerrillas began to force their way into western New Guinea. To avoid bloodshed, a plan was adopted to turn over the disputed territory to the UN. Then, in 1963 western New Guinea was incorporated into Indonesia. More recently relations between Indonesia and Malaysia have been strained because Indonesia lays claim to former British Borneo, now part of Malaysia.

Malaya becomes part of the Malaysian Federation. On August 31, 1963, the Federation of Malaysia, including Malaya, Singapore, Sarawak and Sabah (formerly British North Borneo) came into being. The formation of this new state climaxed changes which had been going on since World War 2.

Britain had first been drawn to the Malayan peninsula because of its strategic position at the crossroads of Southeast Asia. Except for the port and naval base of Singapore, this region was organized in the 1940’s into the Federation of Malaya. Each state in this Federation ruled itself, but over them all there was a British Commission. Like other Southeast Asian lands, Malaya has a large population of Chinese descent. At first, suspicion between the Chinese and the Moslem Malays made it hard for the two groups to co-operate. Also, Malaya was torn by a “hit-and-run war” which Communists waged against the British. Slowly order was restored and in 1957 Malaya became independent within the Commonwealth of Nations.

A major problem for the new Federation of Malaysia was the infiltration of Indonesian guerrillas. Indonesia contends that the Federation perpetuates “colonialism” and includes territory to which it is not entitled and efforts to reach a settlement were unsuccessful.

The Republic of Burma came into existence in 1948. British influence in Burma, which began with the activities of the British East India Company, came to a close soon after World War 2. Early in 1948 the last British governor in Burma handed over authority to the first President of the Burmese Republic. Burma chose not to become a member of the Commonwealth of Nations.

Unfortunately independence did not bring peace, prosperity, or security to the people of Burma. There was conflict between rival groups and Communist armed bands terrorized the countryside.

The situation looked hopeless until a Buddhist leader, U Nu, became Prime Minister. U Nu rallied the Burmese people around the new government and order was gradually restored. Despite aid from the United States and Britain, Burma made slow economic progress.

U Nu’s decision to retire before the 1964 election gave encouragement to left-wing elements and threatened to bring about the disintegration of the Republic. In this crisis Ne Win, head of the armed forces, took over the government. He assumed the offices of President and Prime Minister, dissolved parliament and the courts and established a socialist one-party state.

France loses Indo-China. The French, who had gained control in Indo-China during the 1800’s, were powerless to stop the invading Japanese in World War 2. After Japan’s defeat, French troops tried to restore French authority in Indo-China, but the tide of nationalist feeling was running strong. Moreover, Communist influence had spread among nationalists in Vietnam.

In 1949, in an effort to strengthen their position, the French recognized a new anti-Communist government in Vietnam. At the same time they gave more self-government to two other states in Indo-China, Laos and Cambodia, but guerrilla warfare persisted and the Vietnamese would not rally behind a French controlled government. Moreover, Chinese Communists threatened to take an active part in the fighting. A ceasefire agreement was arranged in 1954. As a result, North Vietnam became a Communist state. South Vietnam, as well as Laos and Cambodia, became independent of France.

Thailand was already independent. Mention should also be made of one other country in Southeast Asia — Thailand (or Siam). This country, unlike neighbouring states, had remained independent when France and Britain were building colonial empires in Southeast Asia. Since the 1930’s Thailand has been a limited monarchy with a constitution. Nevertheless, there have been periods of dictatorial rule and Communist activities have posed a serious threat to the country.

The new nations of Southeast Asia must solve common problems. To sum up, for generations Southeast Asia (except Thailand) had been part of European colonial empires. Then, in a few short years, millions of people unaccustomed to any voice in their government became masters of their fate. The peoples of these new nations represented many different racial backgrounds. Most of them were uneducated. Poverty and disease had always been their lot. Each of the new nations, therefore, has faced similar problems:

(1) Each nation must raise living standards to provide sufficient food, clothing and shelter for its people. To achieve a higher standard of living, improved farming methods and modern implements must be introduced, industry must be developed and trade expanded. Southeast Asia has depended too much on a few exports — rice, tin and rubber. Any downswing in world prices has caused great hardships. The nations of Southeast Asia possess valuable resources but have lacked the capital and skills to develop them effectively.

(2) Each nation must provide stable government. The Southeast Asian states established democratic forms of government, but,having had little experience with democratic institutions, they have found it difficult to make democracy work. Groups within each country want to wield power for selfish reasons and there is the ever-present Communist danger.

To overcome these difficulties, some Southeast Asian governments have tried strong-arm methods or outright military rule. In some cases, more efficient government have resulted but once people yield political power to a dictator, it is not easy to get it back.

Communist penetration in Southeast Asia threatens peace. A major problem which the independent nations of Southeast Asia continued to face was Communist interference. Thus, the division of Vietnam into two countries did not end Communist efforts to take over the free, southern half. American economic and military aid were been able to prevent a Communist take-over in South Vietnam.

Meanwhile, Communist guerrilla activity in neighbouring Laos seemed to threaten not only that country but Thailand as well. In 1962 President Kennedy sent United States troops to Thailand. This prompt action seemingly made it easier for the Soviet Union and the free-world nations to agree on a neutralist government in Laos. Nevertheless, so long as Communist groups in South Vietnam and Laos receive military aid and encouragement from North Vietnam and Red China, it was difficult to restore peaceful conditions.

The United States has sympathized with the surge for freedom in Southeast Asia. The United States has watched with interest and concern the birth of new nations in Asia. In the development of one of these nations, the Republic of the Philippines, the United States played a direct part. The United States began to give the Filipinos some share in their government soon after it acquired the islands. In 1936, with the creation of the Philippine Commonwealth, Filipinos had their own government although they remained under American protection. During World War II, when the Japanese conquered the islands, Philippine troops fought side by side with American soldiers and continued underground resistance during the years of occupation.

On July 4, 1946, the Republic of the Philippines was born, first of the new postwar nations in Southeast Asia. The Philippines, too, had trouble with Communist-led guerrillas until an able democratic-minded leader named Ramon Magsaysay was elected president. Magsaysay ended the disorder by a combination of firmness and fair treatment of the poor farmers who supported the rebels. When Magsaysay was killed in an airplane crash, the Filipinos chose a new president in an orderly election. Relations with the United States have generally been cordial.

American traditions of liberty cause Americans to sympathize with the efforts of Southeast Asians to control their own destiny. Technical advisers have been sent to the countries of Southeast Asia to help the people farm more efficiently and to develop industries. The United States has also provided food, military and economic aid. Our State Department has summarized the situation in these words:

The big problem these nations had to meet was how to raise their people’s standards of living. If they solve this, either alone or with the American help, they would have reason to join the free world in opposing communists. If they could not solve it, they may step into a serfdom worse than any they have ever known — the slavery of a Communist state.

3. How did the Nationalists change the Moslem World?

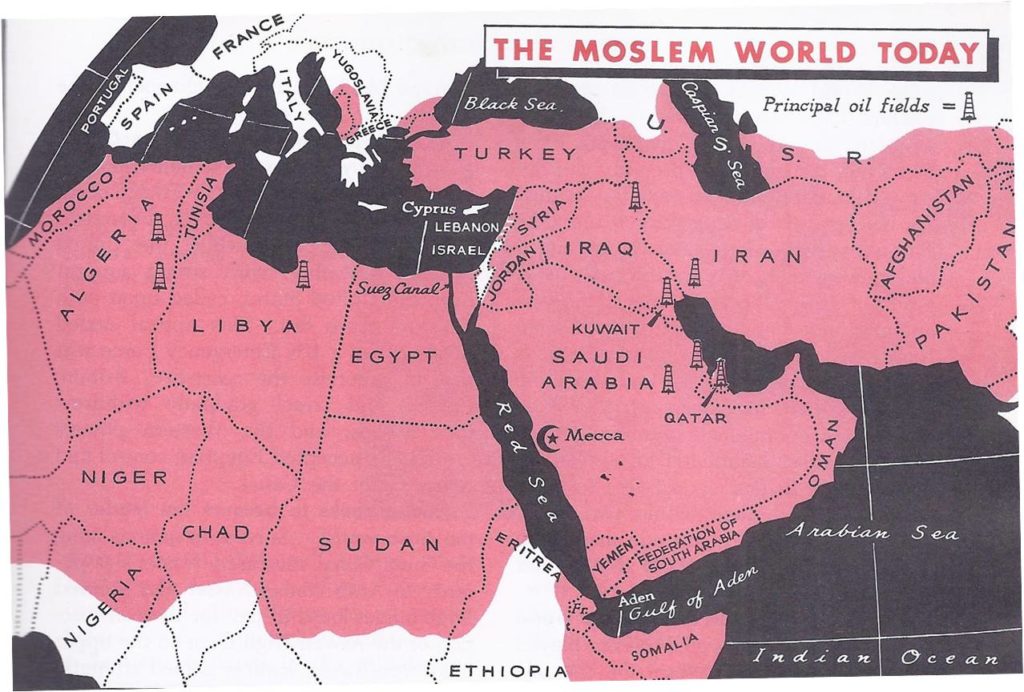

Moslem peoples of South and Southeast Asia formed the new nations of Pakistan, Indonesia and Malaysia. Nationalist beliefs brought changes in the Middle East and North Africa. This is a region steeped in history, in which one civilization after another has risen, prospered and faded away. Here, more than a thousand years ago, the warlike followers of Mohammed welded together a mighty empire. As late as World War I, all of the Middle East except Iran and part of Arabia was dominated by the Ottoman Empire.

Only recently has nationalist independence been achieved. The desire of Moslems in the Middle East to run their own affairs was not satisfied following World War I. Most Arab lands then came under British or French control. Some progress was made toward self-government, especially in Egypt and Iraq, but the continued presence of foreign “advisers” and troops was a reminder that complete independence had not been achieved.

World War 2 provided a “shaking up” in the Arab world as well as in Southeast Asia. The war weakened the Western colonial powers, rule by outsiders had largely disappeared in the Middle East by 1950. Today, as the map shows, the Moslem world is composed of many separate nations.

Oil plays an important role in Arab affairs. Despite the independence of the new states, the Western powers retain strong economic interests in the Middle East. The Middle East produces about one fourth of the world’s oil and possesses about three fourths of the world’s known oil reserves. European and American companies have furnished much of the capital, machinery and technical skill which have made this flow of oil possible.

Oil has been a source both of trouble and of income to the Middle Eastern countries. There was always the danger that a foreign power would interfere in an Arab country to protect its oil holdings, but the Arabs have come to realize that their oil resources gives them great bargaining power in dealing with other countries. Most of the Arab countries have won a larger share of oil income through peaceful bargaining.

Moslems desire a higher standard of living. Millions of Moslems long to be free from the grinding poverty which has been their lot for centuries. Improved living conditions depend on (1) breaking up the huge tracts of land long held by wealthy landowners, (2) improving methods of farming to provide food for the rapidly growing population and (3) spending wisely the income from such exports as oil and cotton. In certain Middle Eastern countries, much of the income from oil is used to provide irrigation, schools and hospitals. To improve living conditions, however, economic aid and the adoption of Western methods of industry and farming were necessary. Unfortunately years of foreign domination had made the Arabs mistrustful of outsiders.

The future of the Moslem world is uncertain. Today the Moslem world is torn by conflicting forces. The masses of people are poorly prepared for self-government. Though the great majority are Moslems, there are sizeable Christian and Jewish populations. Governments range from all-powerful rulers to republics with elected presidents and legislatures. Within the Moslem world, as in Southeast Asia, the Communists have fanned the flames of discontent and hatred of outsiders. Events since World War 2 in (1) Israel, (2) Egypt, and (3) North Africa illustrate the turmoil which prevails in this troubled area.

Many Jews remembered their ancient homeland. The ancient Hebrew civilization that developed in Palestine. The freedom of the Jews came to an end in Roman times and Israel as an independent nation vanished. Scattered all over the world, Jews had a strong common bond in their religious faith. Through the ages they dreamed of a Jewish nation. This dream found expression in Zionism, a movement to establish a modern Israel in Palestine.

In 1917 the British promised to help Jewish people relocate in Palestine, but this promise was qualified by the statement that the “civil and religious rights” of people already in Palestine should not suffer. During the 1920’s and 1930’s Jewish immigrants arrived in Palestine in growing numbers, especially after Hitler began persecuting the Jews. They bought Arab lands and competed with the Arabs for jobs. Riots broke out in-spite of British efforts to keep the peace.

The republic of Israel was formed. World War II brought suffering and death to millions of Jews in those parts of Europe under Axis control. Palestine seemed the only refuge and Zionists pushed their program for unrestricted Jewish immigration and the formation of a Jewish republic. When no plan satisfactory to both Jews and Arabs was found, the problem was referred to the United Nations in 1947.

Although the UN had no better success with the problem, the British withdrew from Palestine in 1948. The Jews immediately proclaimed the State of Israel. The neighbouring Arab countries — Transjordan, Syria and Egypt — then attacked Israel. Through the efforts of an American, Dr. Ralph Bunche, the UN brought about an uneasy truce in 1949. Israeli forces held most of former Palestine. The remaining territory, crowded with Arab refugees from Israel, was occupied by Egypt and Transjordan (now called Jordan).

In spite of its troubled beginnings, Israel has made remarkable progress in building up agriculture, trade and industry. Its energetic people are rapidly transforming a crowded and undeveloped country into a modern natio, but the Arabs, resenting the creation of a non-Moslem state in their midst, have refused to negotiate a boundary settlement. Clashes between Israeli and Arab patrols continue to occur.

The Arabs drew together to oppose Israel. It is easy to understand that Arabs would resent the loss of lands and homes in Palestine, but according to Dr. Bunche, the Arabs had a deeper reason for opposing Israel. They looked upon the establishment of Israel as one more attempt by imperialist Western nations to interfere in the Moslem Middle East.

To protect their interests, the Arab nations organized a league at the close of World War II. This Arab League presented a united front against Israel.

Egypt became the storm centre of the Arab world. The problems that most Middle Eastern countries face in their efforts to become modern nations are clearly illustrated by the recent history of Egypt.

After World War 2, Egyptians resented the fact that a treaty allowed the British to retain troops in the Suez Canal Zone. Riots broke out, British-owned property was destroyed and resentment mounted against the corrupt rule of King Farouk. In 1952 Farouk was forced to leave Egypt and a new government was established by a group of army officers. Among them was an ambitious young colonel, Abdel Gamal Nasser, who soon became president.

Nasser introduced social and economic reforms to help his poverty-stricken people. He also adopted a bold foreign policy. In 1954 Nasser negotiated an agreement under which British troops were to leave the Suez Canal Zone within two years. Nasser’s anti-Western attitude made him popular not only in Egypt but also in other Arab countries.

The Suez Canal crisis endangered world peace. To achieve his goals Nasser played the East against the West. On the one hand, Nasser obtained arms, planes and tanks from Soviet Russia. Then he turned to the Western powers for money to carry out economic reforms in Egypt. When the United States and Great Britain refused to advance a huge sum to construct a great dam on the Nile, Nasser announced the “nationalization” of the Suez Canal. Hitherto the Canal had been managed by a private company and controlled under international agreements. Nasser’s plan was to have the Egyptian government run the Canal and keep the income from tolls.

Britain and France were angered not only by Nasser’s seizure of the Suez Canal but also by his policy of stirring up trouble in neighbouring Moslem countries. They threatened to use force to return the Canal to international control. Then Israel, which had suffered increasingly from Egyptian border raids, took action. Late in October 1956, Israeli forces launched an invasion which brought them within a few miles of the Canal. When Britain and France sent military forces into Egypt to “protect” the Canal, the Egyptians immediately sank ships to block the narrow channel of the Canal.

Egypt kept control of the Suez Canal. Nasser’s army was unable to halt either the Israeli advance or the British-French occupation. Soviet Russia, however, threatened to help Egypt. Meanwhile, the United Nations Assembly, with strong support from the United States, called upon both sides to cease fire. This appeal ended fighting and a UN Emergency Force was sent to supervise the cease-fire. Britain, France and Israel gradually withdrew their troops and the Western powers grudgingly accepted Egyptian control and operation of the Canal.

Nasser seeks to become the leader of the Arab world. Success the nationalists had in nationalizing the Suez Canal increased Nasser’s popularity in Arab lands. Nasser also secured large Soviet loans to pay for the construction of the Aswan High Dam on the upper Nile. Pro-Nasser leaders gained strength, especially in Syria, which also received arms and loans from Communist countries. From 1958 to 1961, Syria was united with Egypt in the United Arab Republic, a name still retained by the latter. Egypt beamed radio broadcasts to the restless people of other Arab lands, urging them to overthrow their governments and to follow Nasser’s leadership.

The United States acts to offset Soviet influence in the Middle East. The Soviet Union was quick to take advantage of unsettled conditions in the Middle East. Arab nations were offered loans and Soviet arms and goods in exchange for raw materials. Fearing a Communist take-over, the United States promised military assistance to any country asking for help against communism. Congress endorsed this “Eisenhower Doctrine” and voted 200 million dollars for emergency aid to the Middle East.

Despite this action, tension increased. In Lebanon, Arab nationalist guerrillas tried to oust the pro-Western government. Lebanon took its case to the UN, accusing the United Arab Republic of helping the rebels. President Eisenhower at once ordered several thousand United States Marines to Lebanon. When Nasser accused the United States of aggression, Soviet Russia supported his claim.

Tension continues in the Middle East. A special meeting of the UN Assembly was called to deal with the Middle East problem. In a surprise move, the feuding Arab nations suggested a plan under which all members of the Arab League, including Egypt, would stop interfering in each other’s affairs. The UN Assembly accepted the Arab plan and a crisis was averted, but tension, marked by outbursts of violence, continued in the Middle East.

Nasser brings about great changes in Egypt. Within Egypt, Nasser pushed ahead with reforms. The estates of wealthy families were limited both in terms of acreage and earned income. Farmers and workers were given half of the total representation in political organizations. Propaganda campaigns were directed against “reactionary” Arab rulers. Aided by German scientists, Egypt developed its own rockets and increased its military capabilities. In later years, the United States and Britain increased their economic aid to Egypt. Nasser, in turn, agreed to pay British citizens for property seized following the Suez crisis.

Moslem states in North Africa won their freedom. In the rest of North Africa, there was growing pressure after World War 2 to end European control. In 1951, the former Italian colony of Libya became an independent kingdom. Libya now had its own ruler, a constitution and a two-house legislature. Five years later, independence came fairly peacefully to the Sudan, another African state most of whose people are Moslems.

In French-controlled Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria the postwar struggle for self-government was a bitter one. When the French proved reluctant to relax their grip on these lands, North African nationalists demanded full independence. The French deposed the Sultan of Morocco and jailed or exiled Tunisian nationalist leaders. Rioting and strikes finally forced the French to bring back the Sultan and to free the Tunisian nationalists. In 1956, Morocco and Tunisia became sovereign nations.

The struggle for independence was especially bitter in Algeria. The Algerian drive for self-government was won only after years of bloody guerrilla warfare. France had conquered Algeria in the 1830’s and governed it as a department of France, not a colony. The Moslems in Algeria were no less determined to win their independence than their kinfolk in Morocco and Tunisia. A million Frenchmen lived in Algeria, but the Arabs outnumbered them 8 to 1.

Most French army officers and many French settlers were determined to keep Algeria French. In 1958, they seized control of the Algerian government, an action that led to a crisis in France. In this emergency, General Charles de Gaulle, the French hero of World War 2, became the new head of the French Republic. He was given almost unlimited power to deal with the Algerian problem. In 1961, the French overwhelmingly approved a peaceful settlement providing for Algerian self-determination. Despite mutiny among French troops in Algeria and the terrorist activities of French die-hards, negotiations slowly went forward. In 1962, the people of Algeria voted for self-government.

Algeria has had to face difficult problems as an independent state. Despite an agreement that there would be no discrimination against Europeans in the new republic, about a third of them left Algeria. This exodus created a serious shortage in the professions, skilled manpower and investment capital. Production dwindled, exports fell off and unemployment was high. Despairing of finding work, Arab Algerians migrated to France. Like other new countries, Algeria needed massive foreign assistance to help meet these problems.

4. How Has the Desire for Freedom Transformed Nationalistic Africa?

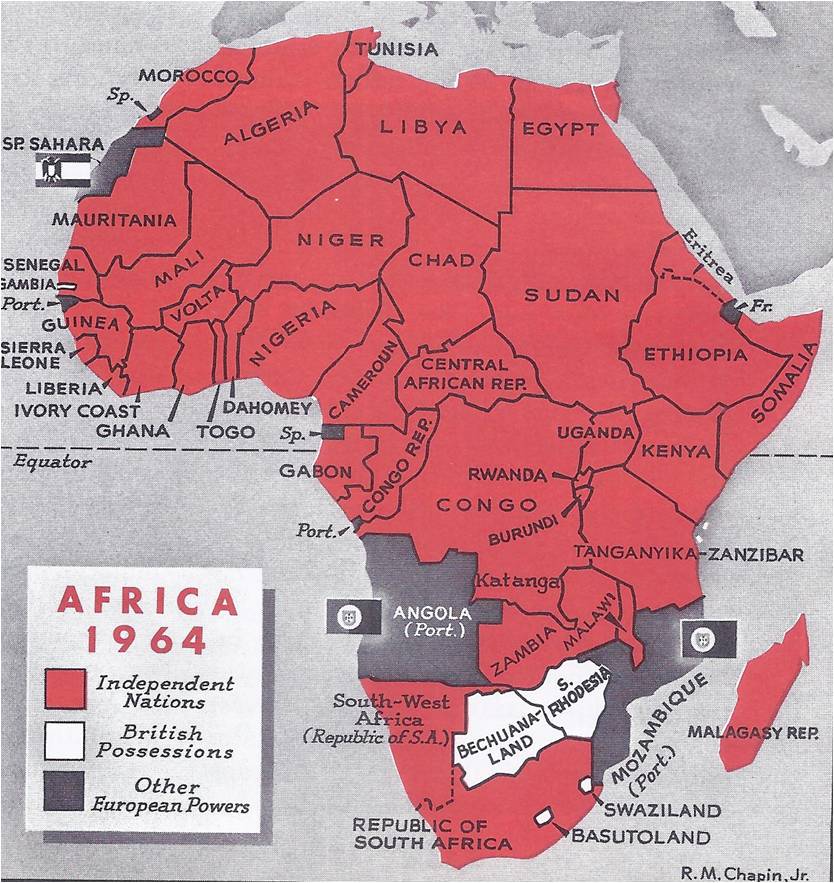

In the early 1900’s all Africa except Liberia and Ethiopia was under foreign rule. Yet today most Africans are citizens of independent nations. A comparison of the map of Africa in 1914 and in 1964 reflects this striking change.

The birth of some new African states was accomplished smoothly; that of others was attended by serious crises. The progress of the African drive for freedom, therefore, is important to the world at large as well as to Africans.

World War 2 started the break-up of colonial empires in Africa. Italy, defeated in World War 2, was the first colonial power to lose its African empire. Ethiopia, which Mussolini had conquered in the 1930’s, regained its independence during the war. In 1952 the former Italian colony of Eritrea was joined to Ethiopia in a federal union. Italy was given a UN trusteeship over another former colony, Italian Somaliland, but in 1960 Italian and British Somaliland were united as a new nation, Somalia.

Britain helped its West African colonies gain independence. In West Africa, tens of millions of Africans had been ruled by a small number of European officials and soldiers. After World War 2, however, Africans in the British Gold Coast and Nigeria formed political parties and demanded self-government.

Britain wisely decided to prepare both the Gold Coast and Nigeria for independence. In 1951, the Gold Coast was granted a new constitution and its assembly chose an African, Kwame Nkrumah, as Prime Minister. The British co-operated with Nkrumah by transferring more powers to his African government. In 1957 the Gold Coast became the independent state of Ghana, a member of the Commonwealth of Nations.

In British Nigeria, too, there was a gradual increase in self-government. Nigeria has the largest population of any African country. In 1960 it became independent and like Ghana, a Commonwealth member.

The next year little Sierra Leone acquired an all-African government and became an independent member of the Commonwealth. In 1961 also the northern part of British Cameroons joined Nigeria; the southern part joined the Republic of Cameroun.

Self-government came later in British territories in East Africa. Moving east and south across the continent, one finds that progress toward African independence in several British colonies has been less swift. One reason is that settlers of European descent have been reluctant to share power with the far more numerous Africans. The Africans, on the other hand, wanted freedom and resented the privileges of the white settlers. In Kenya a secret political society called Mau Mau resorted to savage guerrilla warfare in an effort to drive out the British. It took British troops four years to put down the Man Mau revolt.

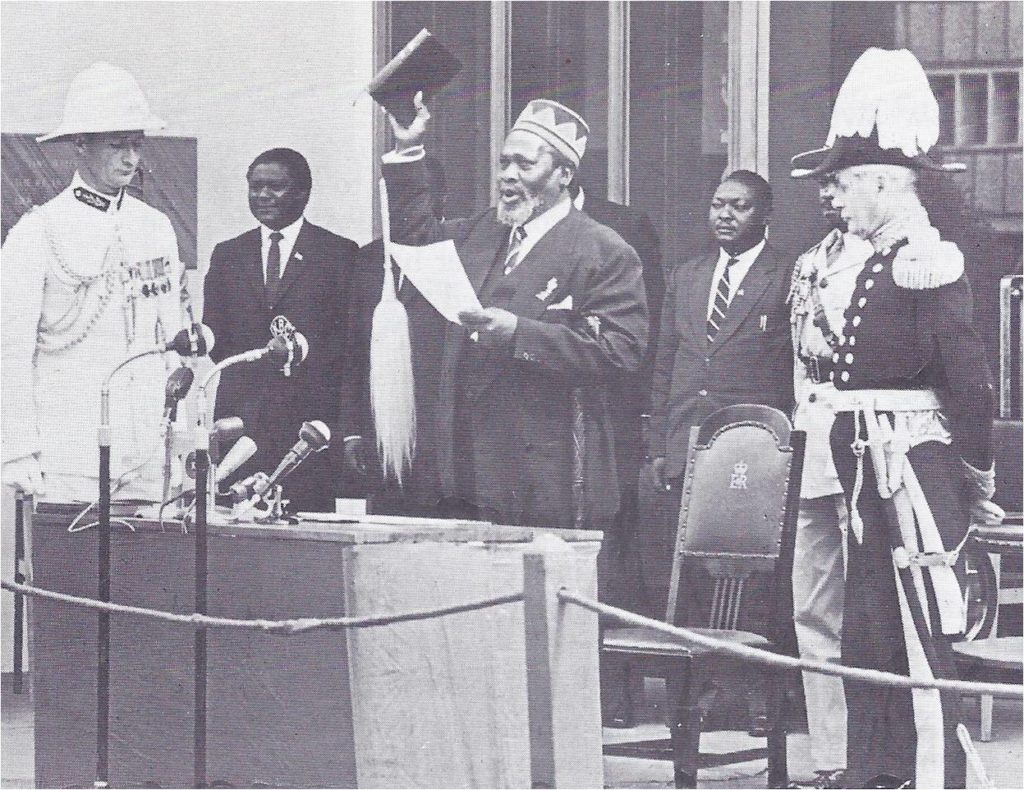

Britain’s answer to this grim warning of African discontent was a plan for more self-government, based on “partnership” between European settlers and Africans. Partnership seemed to work well in Tanganyika. There a young African named Julius Nyerere won the confidence not only of new African voters but of many Europeans and Asians also. In 1960 Nyerere became chief minister; a year later Tanganyika became independent. Uganda, another British territory in East Africa, won independence in 1962.

Elsewhere, partnership was less successful. In Kenya, when Africans won a majority in the legislative council, the prospect of African rule led to an exodus of European settlers. In 1963 a former leader of the Mau Mau became head of the new government. He pledged himself to respect the rights of Europeans. In the federated colonies of Nyasaland and the Rhodesias, Britain’s attempts to establish partnership failed. White settlers claimed that British policies would give Africans control of Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland. The Africans, overwhelmingly denied the right to vote, wished to break up the federation.

Nyasaland, now called Malawi, became independent in July, 1964. Northern Rhodesia achieved independence in October of that year and become known as Zambia. Basutoland and Bechuanaland are moving toward independence. Only the fact that Southern Rhodesia has refused to make its political institutions representative of its population has so far blocked independence for that country.

France’s African territories became independent nations. France was slower than Britain to relax its grip on its vast colonial possessions in West and Equatorial Africa. In 1957, however, all Africans in these lands and on the large island of Madagascar were given the right to vote. Assemblies were elected which chose cabinet ministers to help the still-powerful French governors.

When de Gaulle became premier of France, he proposed a new constitution which would offer the African territories self-government in a federation with France, to be called the French Community. France would continue to have responsibility for defence and foreign affairs. If an African state turned down this constitution, it would receive full independence but would have to do without French aid. All of French Africa except Guinea voted for de Gaulle’s plan.

The French Community began to change almost as soon as it was organized. One by one, then in a rush, the African members of the Community asked for more freedom. By 1960 they had all become independent republics. Though fewer than half of these republics have kept their membership in the French Community, most of them continue to have close relations with France.

Independence created problems for the new African states. Like the new nations of Asia, the African republics are touchy about their new independence and mistrust the former colonial powers. Yet, even more than Asia, independent Africa needs foreign advice and aid in developing its resources and improving the life of its people. The American Peace Corps and foreign aid programs, similar programs of other countries and such organizations as the Commonwealth of Nations and the French Community contributed to this end.

The African nations also need to co-operate with each other. Several are landlocked and must find an ocean outlet for their trade through neighbouring countries. To solve common problems, some of the republics have joined together in customs unions. There also have been moves to form African federations. In 1963 most of the African nations formed the Organization of African Unity. This association began to plan for economic, educational and technological co-operation.

Within their own borders, the citizens of African states face problems of working together. People living near the coast, for example, learned from Western ways, while those farther inland experienced less change. Africans traditionally were loyal to their local tribes rather than to a central government and within each republic there usually were many tribes. Often these tribes spoke different languages and feuded for generations.

To unite their people, some African leaders imposed a strong central government. In Ghana and Guinea, for example, the leaders tried to build up one all-powerful political party, often at the expense of political freedom for other groups. Nigerians, on the other hand, established a federal government in which power was balanced between the different regions. Each region retained considerable control over its own affairs.

Independence brought chaos to the Congo. Many of the problems mentioned were all too clear in the Belgian Congo. Unlike the British, the Belgians had done little to prepare the Congolese for self-rule. Instead of working out a gradual program of increasing responsibility, independence was granted abruptly in 1960. From the very outset the Congo was torn with strife. The new state included many tribes at differing levels of civilization and often hostile to each other. There were disputes between those who favoured a centralized government and those who favoured a federal form of government, as well as sharp clashes between rival leaders. Anti-colonial feeling led to violent attacks on Belgian settlers still in the Congo.

When it appeared that the turmoil might touch off a world crisis, the United Nations sent a security force to the Congo. The UN and individual countries helped to provide food and medical care for the Congolese. The security force prevented the secession of Katanga, a province rich in minerals which considered itself independent and was unwilling to share its tax income with the central government.

The UN security force was withdrawn in 1964, in part because some UN members, including the Soviet Union, refused to pay assessments for its maintenance. Unemployment in the Congo was high, exports declined and uprisings broke out in the outlying provinces. The Congolese army was unable to put an end to strife. In this difficult situation, Moise Tshombe, the ousted head of the Katanga government, was recalled to become prime minister in the hope of bringing order out of chaos.

Explosive situations exist in Africa. In parts of Africa still subject to outside powers or where a small group controls a larger group, there is always the possibility of trouble. Portuguese Angola, where a bloody conflict broke out in 1961, is a case in point. Although the Portuguese have promised the Africans constitutional equality, African leaders demand independence for Angola.

Recent tensions in Africa have not always involved European settlers and Africans. Somalia seeks disputed parts of Kenya and Ethiopia; and has carried on border warfare with the latter. Early in 1964 a bloody revolt overthrew the rule of an Arab minority in Zanzibar. In the Sudan, Negro secessionists battled the Arab government. The numerically stronger Bahuti waged a war of extermination in Rwanda (a former Belgian trusteeship) against their former overlords, the Watusi.

The Union of South Africa goes its own way. In its treatment of Africans, South Africa maintains a strict policy of apartheid, or separation. The population includes about three million Europeans and eleven million others — chiefly Africans, but also a large number of Asians (mostly Indians). These latter groups long demanded higher wages, more rights and some share in the government. In these demands they received some support from English settlers.

Most of the white people, however, are descendants of the Dutch (Boers) who were the chief early European settlers. The National Party, the political party of this group, came to power in 1948, determined to maintain European supremacy. Protests against the government’s harsh treatment of non-Europeans led to bloodshed and the jailing of hundreds of people, many of them White.

When the policies of the Nationalist Party were criticized by other members of the Commonwealth of Nations, the Nationalist leaders called an election. As a result, the Union of South Africa in 1961 became the Republic of South Africa and is no longer a member of the Commonwealth.

The Republic of South Africa has encouraged the immigration of White settlers, has built up its police, armed forces and has strengthened its restrictive laws. It also has moved ahead with plans to create self-governing Bantu (Negro) “homelands,” each with its own parliament and in control of its own affairs except for defense, foreign affairs and the higher courts. The long-range policy would be for all Africans in the country to settle in these territories and to live apart from the Europeans. This policy was denounced by the independent African states. They demanded the expulsion of South Africa from the UN and the imposition of an economic boycott against it.

What is the future? The future of Nationalistic Africa was uncertain. The new nations of this vast continent faced problems of great complexity. With its rich deposits of oil, diamonds, copper and other minerals, Africa was a treasure house for the future, but the development of such resources requires foreign capital and skilled technicians. Can these be obtained without foreign governments seeking to gain advantages for themselves? The average yearly income of the independent African is less than a hundred dollars a person and only about 10 per cent can read and write.

These people, numbering nearly 200 million, wished to run their own affairs, but could they develop stable nationalistic governments able to preserve law and liberty?