Adolf Hitler, stood above the German town of Berchtesgaden, in a large, imposing house in the mountains and stared out a window. It was a fine February day in the winter of 1938 and the snow-covered peaks of the Alps glistened in the clear air.

The man at the window seemed not to see the peaceful mountains. Berchtesgaden was close to the border of Austria and he seemed to see beyond the mountains into the heart of Austria itself — an Austria filled with marching troops‚ cheering crowds and the swastika banners of the Nazis. Staring at this vision, he smiled — for he was Adolf Hitler and he had many reasons to be pleased with himself.

He remembered how he had arrived in Austria after World War I. He had been a vagabond — unknown, shabby, dirty, penniless. Now he was dictator of Germany, the ruler of millions of people. He had come to power in 1933 and looking back on the five years that had passed since then, he smiled again. Things had gone well for him — very well indeed.

From the beginning, Hitler had been determined to smash the Versailles Treaty, which Germany had been forced to accept after its defeat in World War I. The treaty compelled Germany to disarm and give up some of its territory. Quietly and secretly, Hitler had begun to re-arm and when word of this reached the Allies, the nations which had fought Germany, they did nothing.

Among the territories that had been taken away from Germany was the Saar region. Small, but important because of its coal mines, the Saar had been governed by a commission of the League of Nations. In 1935, under the conditions of the Versailles Treaty, the League held a plebiscite, a vote of the people living in the Saar. They were to decide whether the region would continue to be governed by the League, be returned to Germany, or be given to France. More than ninety per cent of the people voted to return the Saar to Germany and Hitler was encouraged.

He was so encouraged, in fact, that he decided he need no longer keep the re-arming of Germany a secret. On March 16, 1935, he publicly announced that he was setting up a peacetime army of about 500,000 men and that military service would be compulsory. The League of Nations protested, but took no action. Britain did take action, but it was action that helped rather than hindered Hitler. Britain agreed to give Germany the right to own submarines and to build a navy thirty-five per cent as large as Britain’s. For all practical purposes, the Versailles Treaty was finished.

MARCH ON THE RHINELAND

While Hitler prepared for war, he talked peace. Germany wants peace! Germany needs peace! Germany will never break the peace! The world seemed to believe him — particularly the British. True, he had frightened France and the Soviet Union, who agreed to go to each other’s aid if the territory of either country was attacked, but that only gave him a further excuse for his next move.

Hitler had his eye on the Rhineland, a region of western Germany along the Rhine River. After World War I, the Rhineland had been occupied by the Allies. Then they had withdrawn their troops and in 1925 Germany signed the Locarno Pact, agreeing that the Rhineland would remain a demilitarized zone. Ten years later, when Mussolini attacked Ethiopia‚ Hitler watched carefully to see what the League of Nations would do. The League’s action against Italy was weak and ineffective and Hitler felt little would be done to stop him from taking the Rhineland. He was ready for his first big gamble.

On the morning of March 7, 1936, German troops began marching into the Rhineland. At noon‚ Hitler made a speech before the 600 members of the Reichstag, the German parliament. He announced that he would no longer abide by the Versailles Treaty or the Locarno Pact and that he was occupying the Rhineland. Cheering and shouting, the 600 men jumped to their feet, raised their hands in the Nazi salute, and cried, “Heil Hitler! Heil! Heil!”

Hitler’s generals smiled at the cheers, but their faces were pale with fear and worry. They knew what a gamble Hitler was taking and had tried to warn him against it. The German army was still small and could send only 20,000 troops into the Rhineland. If the French decided to take action, they could call up many more troops than the Germans, thousands and thousands more. The Germans would be driven out. It would mean the end of Germany’s hopes and plans; it would mean the end of Hitler and the Nazis.

The next twenty-four hours were difficult ones for the German generals. Even Hitler was nervous, though later he would boast of his iron nerve. As it turned out, the French generals were afraid to risk war and advised their government to send no troops to the Rhineland. The British government, too, feared war and refused to support the French if they took action. Besides, Germany was a powerful state and could not be kept out of the Rhineland forever. One British official said that after all, the Germans were “only going into their own back garden.”

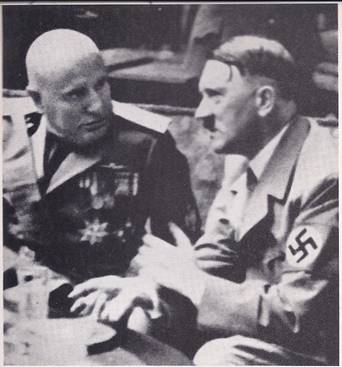

So the British did nothing, the French did nothing and Hitler won his first big gamble. That summer, he tested his military tactics by helping Franco in the civil war in Spain. By October, Hitler had signed an agreement with Mussolini to defend Europe against Communism, setting up what became known as the “Rome-Berlin Axis.” In November, he called an important meeting of his generals. Germany he told them needed more Lebensraum – “Living space.” It must expand, it must have more territory in eastern Europe. Hitler would start by seizing Austria and Czechoslovakia, even if it meant war with Germany’s “hateful enemies,” Britain and France.

Again Hitler’s generals were fearful, but his mind was made up. That same month, he signed an anti-Communist agreement with Japan, the “Anti-Comintern Pact.” A year later, Mussolini joined with them and the Rome-Berlin Axis became the Rome-Berlin-Tokyo Axis. Mussolini even agreed that he would no longer send military aid to Austria if Germany tried to force an Anschluss — a union — of the two countries.

Anschluss. . . Born an Austrian, Hitler had always considered himself a German and believed that Austria should be part of Germany. Many Austrians agreed with him. They spoke a German dialect, their culture was German; they belonged with Germany. They remembered, too, that once Austria had commanded a mighty empire. Now it was a small, weak nation with a population of about seven million. Joined with Germany, Austria might recover the glory it had known in the past. After the end of World War 1, a number of Austrians had called for Anschluss‚ but the Allies refused to allow it, fearing that it would make Germany too strong.

The war had left the Austrian economy in bad condition and Austria was a divided country. The industrial workers, particularly in Vienna, the leading city, supported the Social Democrats. While they favoured socialism, they had no use for the Communist system that had been set up in Russia. They worked for such things as pensions, unemployment insurance and good housing. Opposed to the Social Democrats were the Christian Socialists, who were socialists in nothing except their name.

As time went on, the Christian Socialists became more and more conservative and the feeling between the two parties became more and more bitter. The Social Democrats hid arms and organized a fighting group, the Schutzbund. Prince von Starhemberg organized the Heimwebr, an armed group which supported the Christian Socialists. Often violence broke out and had to be put down by the army and the police. Meanwhile, the Austrian Nazis were growing stronger and it was plain that Hitler intended to seize Austria as soon as he could.

In 1932, little Engelbert Dollfuss — he was an inch less than five feet tall — was elected chancellor. A year later he closed down the parliament and made himself dictator. A Christian Socialist, he smashed the Social Democratic party. When the Socialists called a general strike and tried to defend themselves, there was fighting in Vienna. In February of 1934, 17,000 government troops and Heimwebr men attacked the Socialists’ apartment houses with artillery. A thousand men, women and children, were killed and several thousand wounded.

Dollfuss was determined to keep Austria independent, but Hitler was impatient. In July, 1934, Nazis tried to take over the Austrian government. Disguised as Austrian soldiers, 154 Nazis broke into the Chancellory in Vienna. They shot Dollfuss and let him bleed to death. This time, however, Hitler lost his gamble. He had acted too soon. The Austrian government quickly put down the Nazis. Britain and France insisted that Austria remain independent and Mussolini, who had not yet signed the Rome-Berlin Axis agreement, backed them.

Hitler was still too weak to risk war and he realized at once, that he had made a mistake. He told the world that he had had nothing to do with the events in Austria. He regretted the “cruel murder” of Dollfuss and in 1936, he signed an agreement with Kurt Schussnigg, the new head of the Austrian government, recognizing Austria’s right to be independent.

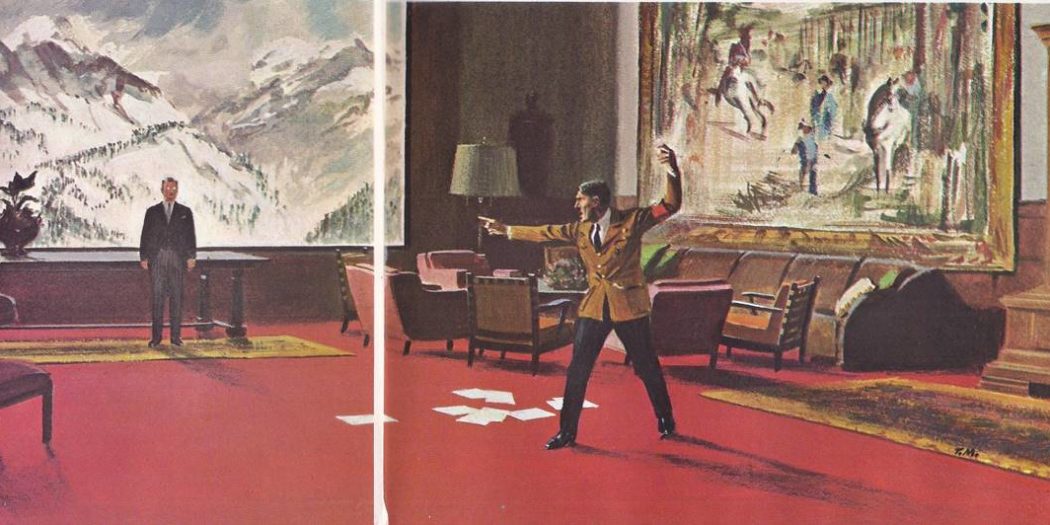

That had been in 1936 and this was 1938. Germany was now much stronger and Hitler felt that no one could keep him from taking Austria and then Czechoslovakia. As the first step in his plan, he had arranged for a meeting with Schussnigg. Standing at the window of his house in Berchtesgaden, Hitler reviewed his plan and found it good. The meeting was to take place here, this very day and it was almost time for Schussnigg to arrive. Yes, it was almost time — and Hitler was ready.

Accompanied by three of his generals, he went outside to greet Schussnigg. The two men were soon left alone in Hitler’s study, the room with the big windows overlooking the mountains. Schussnigg, always polite, said something about the view and the weather.

Hitler burst out, “We did not gather here to speak of the fine view or the weather!”

That was only the beginning. For hours, Hitler blustered and threatened. He was determined to end the problem of Austria. He would allow no one to stop him. Whoever stood in his way would be crushed and who would come to Austria’s aid? Italy? He and Mussolini saw eye to eye. England? England would not move a finger. France? France could have stopped him in the Rhineland, but now it was too late.

Before the day was over, Schussnigg was handed a document to sign. Among other things, Austria was to allow the Nazis to be a legal party again and two Nazis were to be appointed to the cabinet. Schussnigg knew that this would mean the end of Austrian independence and he hesitated.

Pacing up and down, Hitler said, “There is nothing to be discussed. . . . You will either sign it as it is and fulfill my demands within three days, or I will order the march into Austria.”

Schussnigg signed and returning to Austria, carried out Hitler’s demands, but he was still hopeful. While the Nazi propaganda machine thundered and the Austrian Nazis demonstrated and rioted, he tried desperately to save his country. Although he was a Christian Socialist, he turned for support to the Social Democrats. He allowed them, like the Nazis, to be a legal party again and then he had an idea. He announced that on March 13 he would hold a plebiscite. The Austrian people would themselves vote on whether or not they wanted Anschluss with Germany.

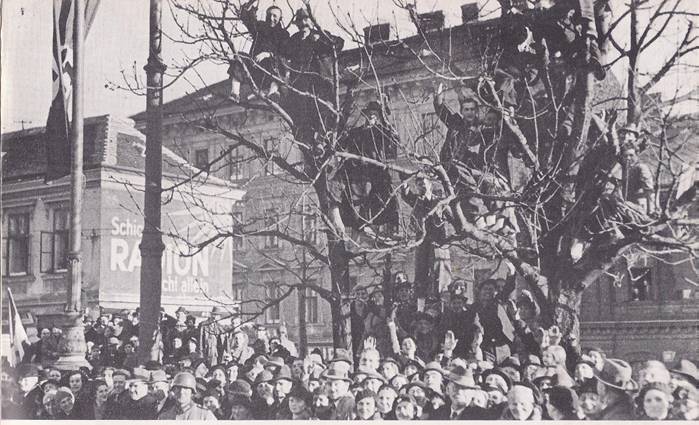

Schussnigg’s plebiscite was never held. On March 11, Hitler threatened to invade Austria and forced Schussnigg to resign. A Nazi mob tramped through the streets of Vienna, shouting, “Sieg Heil! Heil Hitler! Heil Hitler! Hang Schussnigg! Hang Schussnigg!” The next day Hitler officially declared that Austria was part of Germany and Schussnigg was arrested. On March 14, units of the German army and Hitler himself entered Austria. Soon Jewish homes and shops were looted, and thousands of Jews were thrown into concentration camps. Storm troopers forced Jews to get down on their knees and clean the streets and public toilets, while crowds of Austrians watched, grinning.

Excited and overcome with joy, Hitler said, “I believe it was God’s Will to send this Austrian boy to the Reich and permit him to return to unite the German people. . . . Everything that has happened must have been preordained by the divine will. . . . I have proved that I can do more than the dwarfs who were running the country into the ground. . . . My name will stand forever!”

Just as Hitler had predicted, no country had come to the aid of Austria. Its seven million people now belonged to him. Again he had gambled and won; now he could go after Czechoslovakia.