A victorious Athens was thanks to Themistocles, whose farsighted proposal that the Athenians should fight the Persians at sea rather than land, paved the way for the defeat of King Xerxes.

Greece was threatened by the advance of the Persians, but even in the face of such a threat, the Greeks were unable to unite as a nation. The basis of Greek life was the “polis” or city-state and the concept of nationhood was completely foreign to this system. Eventually, however, a Hellenic league of Greek cities was formed, led by Athens and Sparta. In 480 the Persians were defeated at sea at Salamis and in 479 on land at Plataea. Had the Persians been the victors it is hard to tell how our civilization would have developed. Possibly democracy, as we know it, would never have survived. Paradoxically it was precisely because of Greece’s weakness — the independence of the city-state — that democracy, particularly in Athens, reached its highest peak of development. Thanks to Salamis it was handed on to future generations, enshrined in the legacy of Greece.

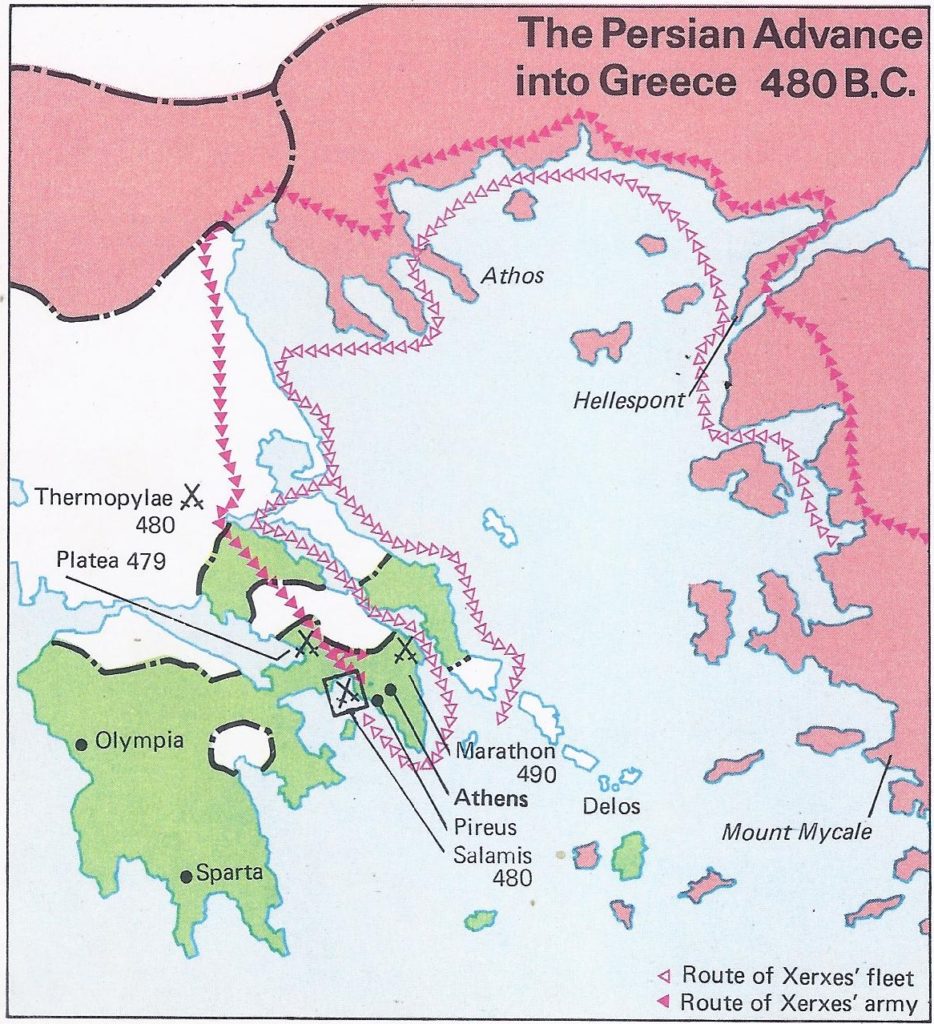

The Assembly on the Pnyx, Athens’ “parliament hill,” was packed; this would be a crucial debate. The mighty Xerxes of Persia, with the greatest invasion force that Greece had ever seen, had crossed the Dardenelles and was now advancing inexorably across Thrace towards Macedonia. His engineers had even cut a canal through the peninsula of Mt. Athos for the safe passage of the force’s navy. The ruling dynasty of Thessaly had decided to collaborate with the invader and the Macedonians had given him earth and water in token of submission. The district of Boeotia was rife with Persian sympathizers. The Spartans were ready to make a stand against Xerxes; the crucial question was, where would they make it? Their traditional line of defense was the Isthmus of Corinth. If they chose to hold that line now, Athens — to the north — would be left in isolation, exposed to the advance of the Persian war machine.

In two months or less, if nothing was done to halt him, Xerxes’ fleet and army would reach Attica. The chance of the northern Greek states holding out — or indeed not actively collaborating with Xerxes — was plainly slim. Worse still, Xerxes had publicly declared that the prime purpose of his expedition was to punish Athens for the part that she had played, nearly twenty years earlier, in the revolt of Greek cities in Ionia against Persia. Any other state, then, might expect reasonable treatment from the Persian king; the Athenians could expect no mercy. Their alternatives were flight or resistance. The Delphic Oracle — while merely counseling other states to remain neutral — had already advised flight for the Athenians.

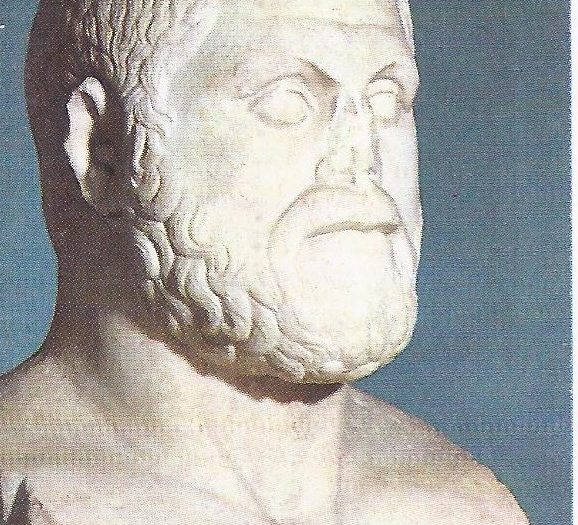

The big, thick-set man who stood on the speaker’s platform of the Pnyx on that fine day in 480 B.C. was already a familiar figure. The crier’s voice called out: “Pray silence for Themistocles, son of Neocles, of the Phrearri parish.” Themistocles must have stood for some time, perhaps waiting till the buzz of voices died away, trying to sense the Assembly’s mood as he gazed out towards the plain of Marathon. There, he would have recalled, once before, only ten years earlier, Athenians had beaten off a Persian invasion. Themistocles had fought and fought well, in that battle; so had many of those waiting this day for him to speak, but this crisis was different. At Marathon a citizen-army — men of property and breeding, who could afford their own armour had marched out to defend their city and their country estates. Some of the men in his audience today, Themistocles knew, were anxious to do so again. Yet no infantry force Greece could put in the field would hold up this new invasion for long. To fight the Persians at sea was the only chance.

Three years before, against strong conservative opposition, Themistocles had put through a motion for Athens to build two hundred new warships, financed by the proceeds of a rich new lode in the Laurium silvermines. By June, 480, that fleet was ready and Themistocles was determined to use it. We have no record of his actual speech to the Assembly on that historic occasion, but the arguments he employed are not in dispute and he made victorious Athens.

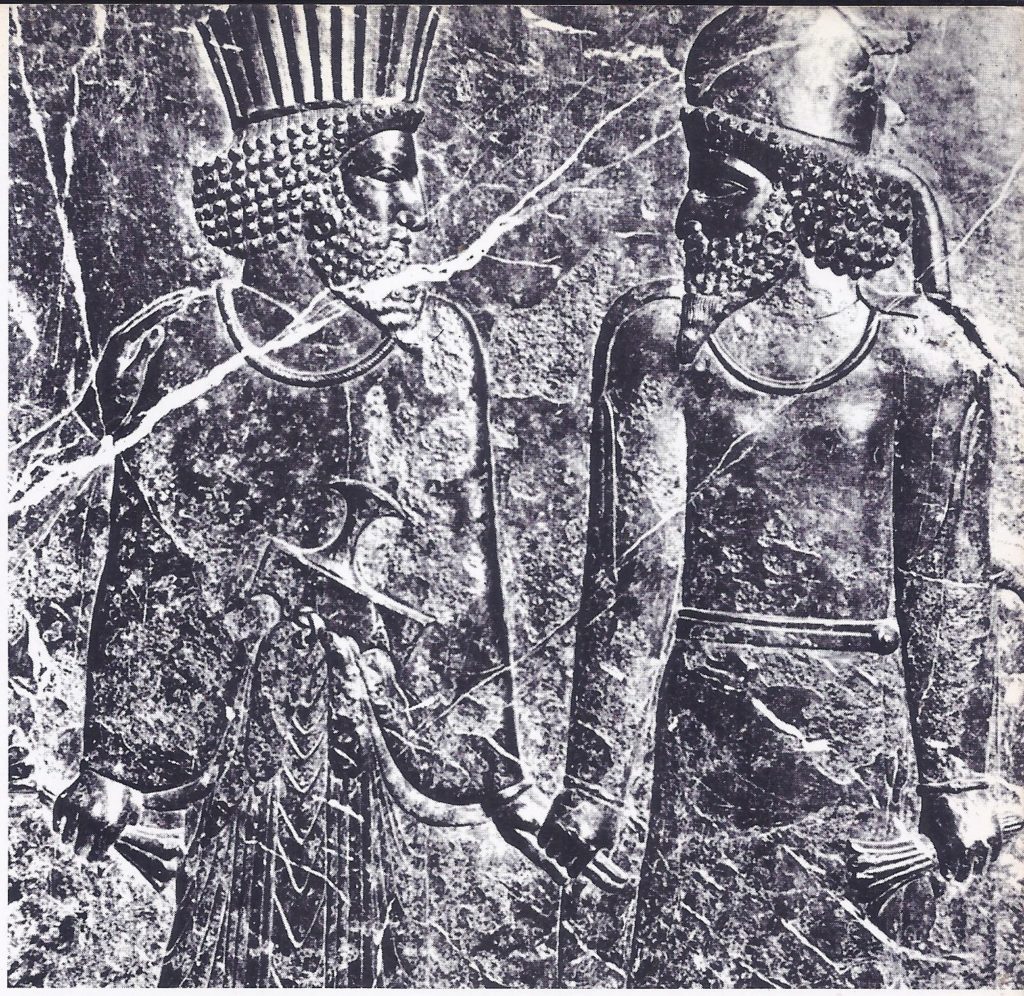

Ever since the accession of King Darius, forty-two years earlier, in 522, Persian expansion had threatened Europe. Meanwhile, Egypt and Libya had fallen; so had several key islands in the eastern Aegean Sea. Darius had then boldly crossed the Bosporus, annexed Thrace and secured Macedonia’s submission. The collapse of the Ionian Revolt (499-494) had made an invasion of the Greek mainland inevitable. In 490 the invasion came, to be repulsed by the Athenians at Marathon. Rebellion in the Persian empire and the death of Darius in 486, had merely postponed the next inevitable attack. Now Darius’ son Xerxes was on the march.

Hysterical rumours estimated Xerxes’ fleet at over 1,200 ships and his army at well over a million (the actual figures are probably 650 and 180,000 respectively). Themistocles’ attempt to sell a naval-defense policy to the Greeks had already once fallen on deaf ears. The Hellenic League — a group of those Greek states determined to resist had voted instead to send a land force of 10,000 men to hold the pass of Tempe in northern Greece and Themistocles had agreed to serve as its commander. The expedition ended in a complete fiasco. The Greeks found that Xerxes could easily out flank them through central Greece; and the Thessalians, on whose help they had relied, went over en bloc to the enemy. It was immediately after this setback that Themistocles made his great speech to the Athenian assembly.

The Persian Menace

In a few days, there was to be an emergency meeting of the Hellenic League at the Isthmus of Corinth; but how the states would vote no one, at the moment, could foresee. Themistocles hoped for the acceptance of his own plan — a land-and-sea holding action at the pass of Thermopylae and in the waters off Artemisium. Yet he was a realist. No one had forgotten that the Spartans had arrived too late for Marathon. Worse still, they might vote to hold the Isthmus line and let everything to the north go. Cynics at Sparta might sacrifice their rival Athens to Xerxes and allow Persia to run northern Greece in the same laissez-faire way that she did Ionia. Sparta, south of the Isthmus, would retreat still further into isolation. In either case, Themistocles realized, adequate plans must now be made for the protection of Attica.

Thanks to archaeology, we now know what those provisions were made. In 1959 Professor Jameson of the University of Pennsylvania discovered a third century B.C. inscription which preserves, in edited form, the motion passed by Themistocles in June, 480 B.C. Here are the key clauses from it, in Jameson’s translation:

Gods. Resolved by the Council and People. Themistocles, son of Neocles, of Phrearri, made the motion. To entrust the city to Athena, the Mistress of Athens, and to all the other gods to guard and defend from the Barbarian for the sake of the land. The Athenians themselves and the foreigners who live in Athens are to send their children and women to safety in Troezen, their protector being Pittheus, the founding hero of the land. They are to send the old men and their movable possessions to safety on Salamis. The treasures and priestesses are to remain on the Acropolis, guarding the property of the gods.

All the other Athenians and foreigners of military age are to embark on the two hundred ships that are ready and defend against the Barbarian for the sake of their own freedom and that of the rest of the Greeks along with the Lacedaemonians, the Corinthians, the Aeginetans, and all others who wish to share the danger . . . When the ships have been manned, with a hundred of them they are to meet the enemy at Artemisium in Euboea, and with the other hundred they are to lie off Salamis and the coast of Attica and keep guard over the land. In order that all Athenians may be united in their defense against the Barbarian, those who have been sent into exile for ten years are to go to Salamis and stay there until the people come to some decision about them . . .

To get this motion passed was a real triumph for Themistocles: its measures were bound to be unpopular with those who had an old-fashioned attitude towards defending hearth, home and the shrines of one’s ancestors. What landed gentleman would support a motion proposed by a man whose backing came from the “sailor rabble” of Piraeus not least when its direct consequence might be the destruction of all farms and estates in Attica? When he called on Athens to evacuate Attica and trust to the fleet, Themistocles had the whole weight of prejudice and tradition against him.

Yet, somehow, he won. He argued that the “wooden wall” which — according to the Delphic prophecy — would not fail Athens in her hour of need must refer to the fleet. He spoke of freedom and the glories of sacrifice. He changed his mood, becoming brisk and practical as he outlined the evacuation plan in detail and he ended with a call to unite against the Barbarian. When he stopped speaking, the Assembly rose and cheered.

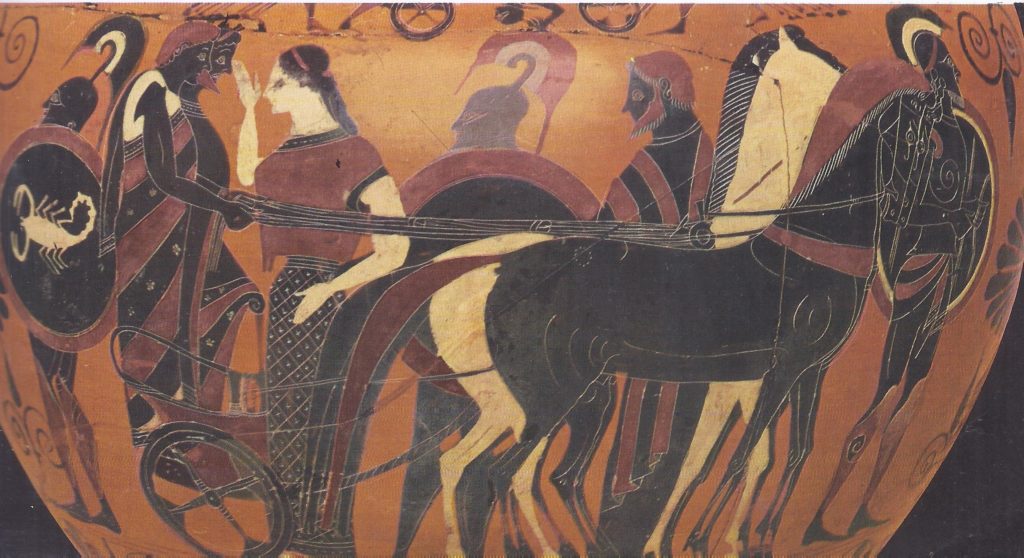

The Hellenic League, too, was swayed by Themistocles’ arguments. Naval and land forces moved north to hold the Thermopylae-Artemisium line. The army, commanded by Sparta’s King Leonidas, included some 4,000 Lacedaemonians, of whom only 300 were full Spartan citizens. Athens provided by far the largest contingent in the fleet: 147 triremes out of an initial 271. The priests at Delphi advised the Greeks to “pray to the winds.” Meanwhile the Great King’s host trudged southwards.

By the end of July the Greek fleet and army were in position. On August 12 the Persian fleet was anchored in minor harbours and anchorages around Cape Sepias and along the Pallene peninsula. Fire-signals from Skiathos brought the news to Artemisium. To prevent dissension, Themistocles had surrendered his command to the Spartan Eurybiades, but one can see his hand in what followed. The Greek fleet retreated to Chalcis, in the Straits of Euboea: Themistocles hoped to tempt the Persians into fighting in a confined space. Xerxes had dried out his fleet at Doriscus; the Greeks had not dared risk a similar operation. Thus the Persian vessels were now faster and more maneuverable than those of their opponents. Somehow this disadvantage had to be neutralized.

At dawn on August 13 the meltemi, the seasonal northeast winds, began to blow and for the next three days the Persian fleet was storm-bound, with heavy damage. As early as the fourteenth, the Greek naval commanders learned of this disaster — and heard also that the Persian land forces were approaching Thermopylae. The fleet now returned to Artemisium: it was strategically vital that King Leonidas should not have his right flank exposed. It was essential to maintain close liaison between land and sea forces.

For a day or two, nothing happened. The storm bIew out by August 16 and the battered Persian fleet limped into Pagasae harbour, but on the following day Xerxes prepared for action. A squadron of two hundred ships was sent round Euboea to take the Greek fleet in the rear; perhaps news of this action drove the Greeks to fight their first naval engagement, on August 18. This clash coincided with the first land assault on Thermopylae and it was equally inconclusive.

Praying to the winds seemed highly efficacious. Xerxes’ outflanking squadron was now caught in a driving rain off the Hollows of Euboea and was largely destroyed. Since the danger of an outflanking movement was now mostly removed, the Greeks reinforced their Artemisium fleet with fifty-three ships relieved from the duty of guarding Attica. They hoped to snatch a decisive naval victory from the Persians. They were disappointed. On August 20 a bitter battle was fought with Xerxes’ remaining squadrons, but its outcome was indecisive. Yet the Greeks still held the straits.

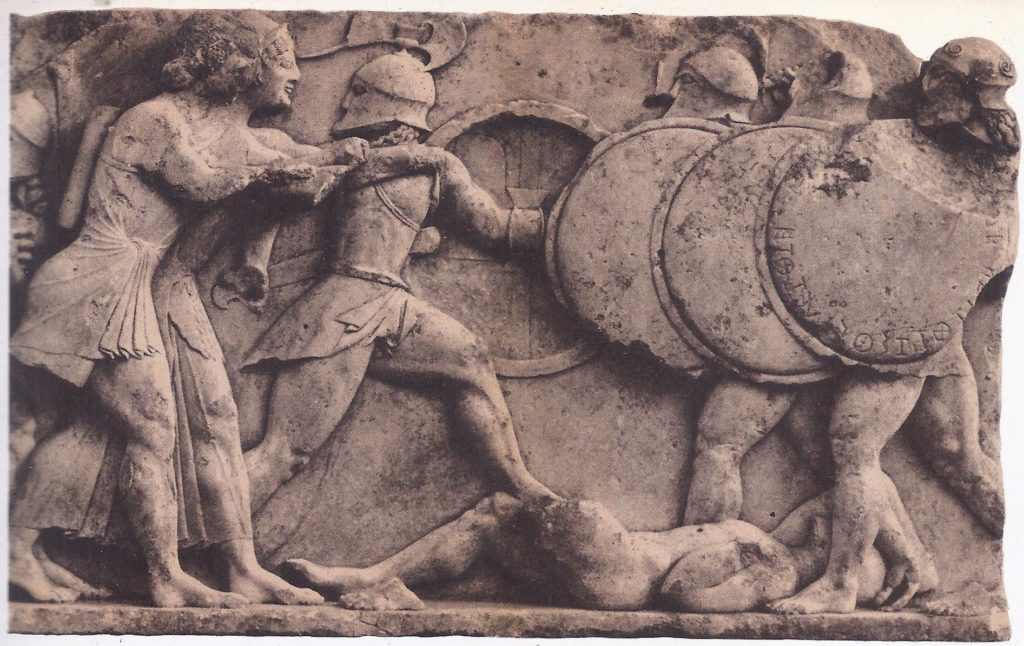

“They learned from their own behavior in the face of danger,” Plutarch wrote, “that men who know how to come to close quarters and are determined to give battle have nothing to fear from mere numbers of ships . . . they have simply to . . . engage the enemy hand-to-hand and fight it out to the bitter end.” The engagement at Artemisium paved the way for Salamis, but while this encounter was taking place, another more famous and more desperate battle had been fought in the pass of Thermopylae.

For two days King Leonidas and his inadequate force held the pass against endless assaults by Xerxes’ infantry. Then a traitor showed the Persians a concealed path over the mountains, a natural “corridor” by which Leonidas could be taken in the rear. The Phoenicians guarding it fled, possibly by design; the sources are not clear. At this news the bulk of the Peloponnesian units withdrew south. Once Xerxes’ cavalry was through the pass, those retreating Greek troops would be cut to ribbons. So Leonidas, without fuss or bother, made his last stand. The Spartans fought to the last man. When their spears were broken, they fought with their swords and after that, with their hands and teeth, but they went down at last and the pass to the south lay open.

Thermopylae and Artemisium were far from useless sacrifices. Their effect on Greek morale was incalculable and they delayed the Persian advance just long enough. More important and in conjunction with those two lucky storms, they had destroyed so many Persian ships and men that Xerxes hesitated to make the one move almost guaranteed to win him the campaign: a division of his forces. Demaratus, the renegade Spartan king who was acting as the Great King’s adviser, urged Xerxes to detach a task force of three hundred ships to the Peloponnese, while at the same time pressing home his attack on Athens. However Xerxes’ brother Achaemenes vetoed such a project — too many ships had been lost already.

Themistocles’ Strategy

Battered and bloody, the Greek fleet withdrew south from Artemisium under the cover of darkness. The Athenians alone had had about half their vessels put out of commission. The allies made directly for Salamis, where the reserve fleet was to join them. The Athenians meanwhile sailed to Phaleron, to complete the evacuation of Attica before Xerxes’ advance land forces crossed the frontier. The news that Themistocles and his exhausted crews received at Athens was not encouraging. The Peloponnesians predictably were reported to be “fortifying the Isthmus and letting all else go.” Some men still hoped to hold the Cithaeron-Parnes line with Spartan support. Again Themistocles acted swiftly and decisively. A token garrison was left on the Acropolis; within forty-eight hours the evacuation of Attica was complete and the allies were firmly established on Salamis. Even then, Peloponnesian representatives at the council of war that followed were still in favour of pulling out and holding the Isthmus line.

Meanwhile the Persian army, virtually unopposed, was pressing on southwards. Delphi, mysteriously, was spared — perhaps as a reward for so many pro-Persian oracles. Boeotia surrendered and collaborated. News came that the Persians were already in Attica, burning the countryside as they came. About August 27, Xerxes’ advance column clattered through Athens’ deserted streets to the foot of the Acropolis; his fleet reached Phaleron two days later, leaving behind a trail of smoke-blackened coastal villages. Soon after the beginning of September, the Persian army arrived in force and on the fourth or fifth, watchers from Salamis saw a pall of smoke rise over the burning Acropolis.

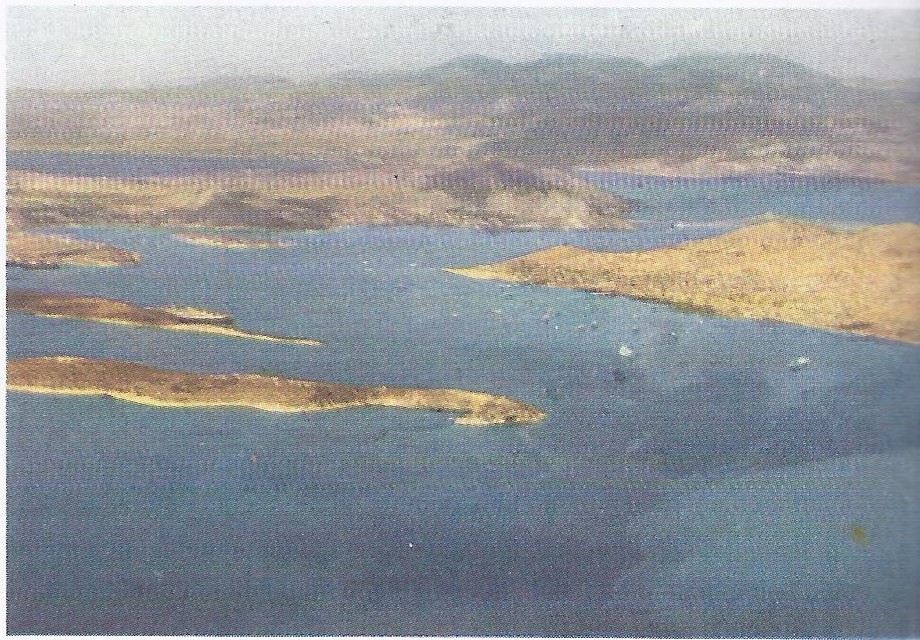

Defeatism was in the air: several commanders were so alarmed that they walked out of a council meeting and “hoisted sail for immediate flight.” Again there was talk of a retreat to the Isthmus. Themistocles told Eurybiades, in private, that once this happened, the whole allied fleet would break up. The Greeks, notorious individualists, possessed singularly little team spirit. In public, however, Themistocles argued that sea and land strategy were indissoluble. To fight in the Salamis channel would give the Greeks every advantage. In a confined space, tactics were more important than numbers or speed.

Finally, Themistocles resorted to threats: if they refused to fight at Salamis, he said, he would pull out the entire Athenian contingent. At this, Eurybiades gave in and the other commanders followed suit. Xerxes had problems of his own. He could not attack the Peloponnese by sea until he had dealt with the fleet at Salamis. Whatever he did, he must act fast: it was already mid-September. Themistocles, who was a first-class judge of human nature, guessed that the Great King would grasp at anything that seemed to offer a quick solution. The Athenian therefore summoned his children’s tutor, an Asiatic Greek named Sicinnus and secretly sent him to Xerxes with a letter. In this letter Themistocles made three Claims: that the allies were quarreling among themselves, that many would desert or change sides in a showdown battle and that some already planned to slip away to the Isthmus during the night. If Xerxes blocked both exits from the straits, Themistocles advised and struck at once, the Great King would capture or destroy the entire Greek fleet.

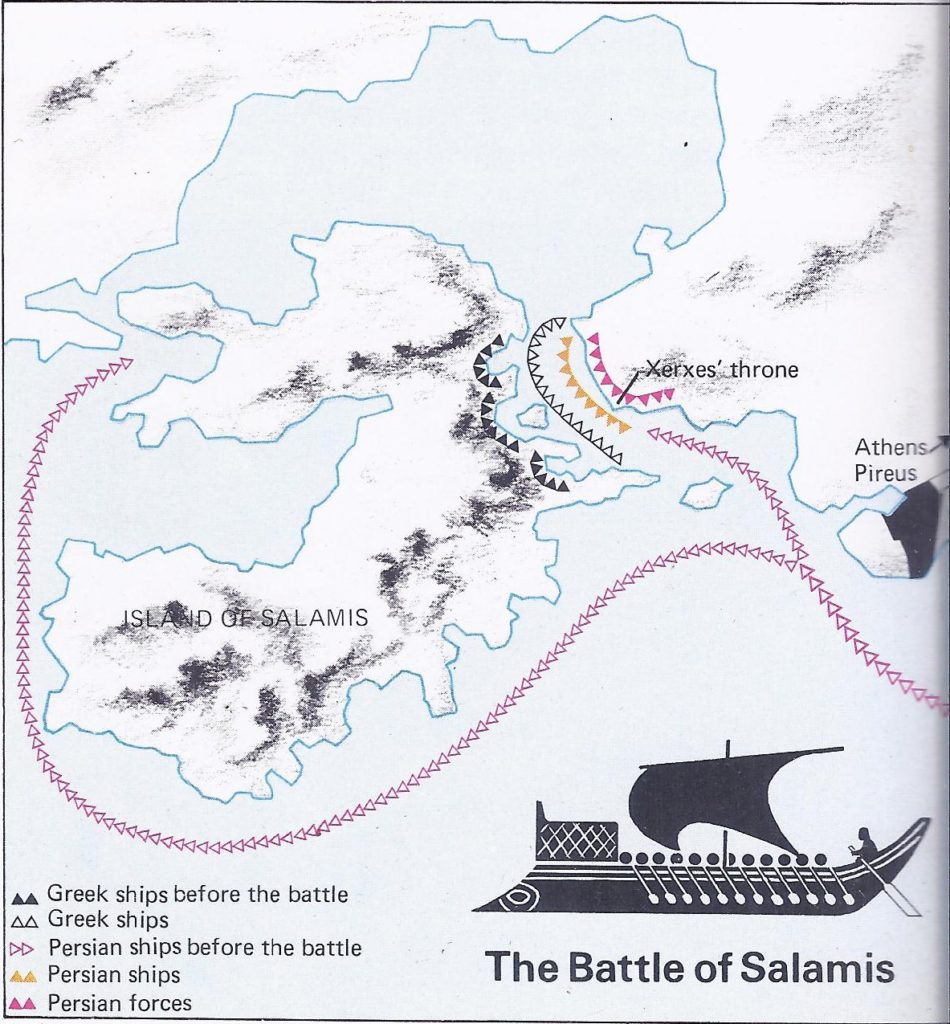

What Themistocles wrote was not only plausible, but in many respects was all too true. It was also just what Xerxes wanted to hear and he was therefore completely taken in by the deception. The duped Great King acted at once. The Egyptian squadron was sent to block the channel between Salamis and Megara. A large body of Persian infantry landed on the island of Psyttaleia at the entrance to the narrows. Other Persian and Phoenician squadrons moved up along the Attic coastline. Thus Xerxes’ crews were up and active most of the night — and exhausted by morning. Xerxes had taken the bait, the blockade was complete. It only remained to be seen whether he would press home his attack into the sound. On that everything hung. As was said afterwards, all Greece that day stood on the razor’s edge. At first light of day on September 29, the Greek crews assembled by their ships, ready for action. Themistocles was chosen to address them and his speech, on the theme “All is at stake” became legendary. It fired his men’s hearts and fiercely elated, the crews rowed out into the channel. Something more than mere patriotic fervour was needed to win the day and accounts of the battle suggest that meticulous planning had been undertaken well before the battle actually took place.

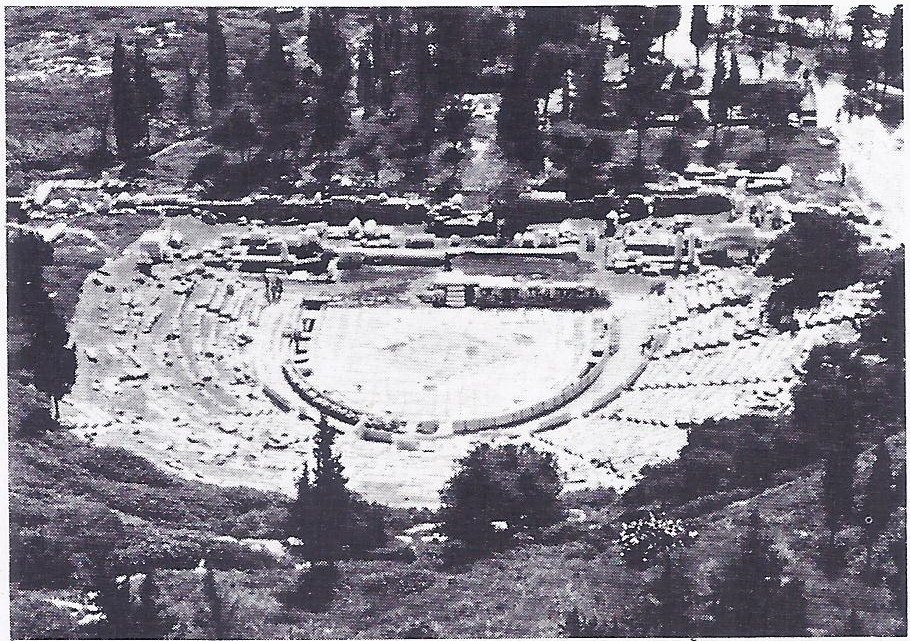

The allied contingents were distributed among three harbours — Salamis itself and the two shelving inlets north of the town, where the main force was concentrated. In Salamis harbour, detached from the fleet’s battle formation were stationed the crack squadrons of Aegina and Megara. The northernmost position of the main force was held by the Corinthians, who had orders to guard the Bay of Eleusis against a surprise attack by the Egyptians in the Megara channel. The central allied line — Spartans on the right wing, Athenians on the left — moved out from shore to form beyond St. George’s Island. At first the ships peeled off northwards a critical moment, for this move was a carefully calculated feint to lure on the enemy.

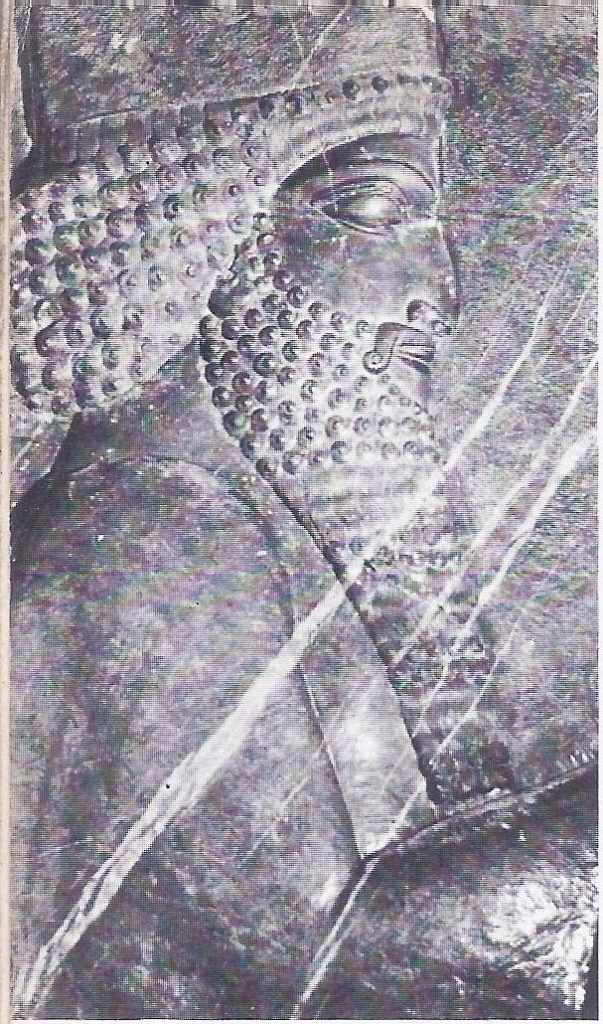

Seeing the main part of the fleet heading north, the Persians must have believed that it was what they had been told to expect — a demoralized Greek retreat. A decision was taken at once. The Persian rowers bent to their oars and the line moved forward through the narrows into the sound. From his golden throne, set on an eminence above the Attica shore, Xerxes watched their advance — at first with pride, then with mounting anxiety and finally in anguish and despair. As more and more of his warships crowded into the narrows, they began to foul each other. Some had to be pulled out of line, causing considerable disorder. Xerxes was not the only commander to discover that it is much easier to start an advance than it is to stop it.

The leading Persian squadrons naturally slackened their speed when the Greeks — in battle formation now and far from demoralized — came sweeping towards them in a wide crescent. To create yet greater chaos, the Persian admiral was killed almost at once and his subordinate officers began shouting contradictory orders from every side. With such a press behind them, they could hardly have backed water now even if they had so wished. In a few minutes the whole channel was a logjam. The only alternative left to the Persians was to attack, but the Greeks, with more room to manoeuvre, encircled them in a tightening noose, pressing them still closer, brazen rams smashing through their timbers or shearing off their oar-banks. As the jammed Persian vessels struggled to withdraw, the Aeginetan squadron moved out from its reserve position and took them in the flank.

As the battle turned into a rout, Xerxes sprang up from his throne in agonized and impotent fury. Aeschylus, who fought at Salamis, afterwards memorialized the scene in his play The Persians:

Crushed hulls lay upturned on the sea, so thick you could not see the water, choked with wrecks And slaughtered men: while all the shores and reefs Were strewn with corpses. Soon in wild disorder All that was left of our fleet turned tail and fled. But the Greeks pursued us, and with oars or broken Fragments of wreckage split the survivors’ heads As if they were tunneys or a haul of flsh: And shrieks and wailing rang across the water Till nightfall hid us from them.

A Golden Age for Victorious Athens

Against all odds and at the eleventh hour, Greece had been saved; and not even his many bitter enemies could deny that Themistocles had saved her. Persian strategy had depended on close cooperation between fleet and army; the fleet was now virtually out of action and the vast land force had no option but to retreat. Xerxes’ son-in-law Mardonius remained in Greece, with perhaps 60,000 men; but a year later, in 479, an allied army led by the Spartan Regent Pausanias destroyed him also. Hostilities with Persia continued, sporadically, for years, but the spectre of invasion and occupation vanished after Salamis, never to return.

Writing of Leonidas at Thermopylae — but it might equally well have been of Themistocles at Salamis — William Golding says, in a memorable and moving essay: “If you were a Persian . . . neither you nor Leonidas nor anyone else could foresee that here thirty years’ time was won for shining Athens and all Greece and all humanity . . . A little of Leonidas lies in the fact that I can go where I like and write what I like. He contributed to set us free.” Salamis was the triumph of free men over autocrats, of men who won, against odds, precisely because they were fighting for an ideal. Only free men, proud of their freedom, could have produced the imperishable achievements in architecture, sculpture and drama that have made Athens immortal: the vision of a Phidias, the thundering choruses of Aeschylus, the proud, gay, confident humour of Aristophanes. Under Persian overlordship, Athens might have achieved much; but not this and not in the same spirit.

This story does not have a happy ending; not, at least, in the short run. Less than ten years after his great victory, Themistocles was hounded into exile. He eventually died by his own hand, a reluctant hanger-on at the court of the country he had defeated, Persia. Pausanias was executed by his own countrymen, probably on a trumped-up charge. Under her new leaders, Athens, having fought in the name of freedom, proceeded to build an imperial system of her own, of “subject-allies” who were not barbarians, but Greeks.

The fifth century, which had dawned so brightly, ended in defeat and despair, with the long, drawnout struggle between Athens and Sparta. Yet there is a moral here. Freedom means, in the last resort, the freedom to go to hell in your own way; better Athenian irresponsibility on an Assembly vote than benevolent autocratic paternalism. That is the lesson which Salamis bequeathed to Greece, to Europe and ultimately to the whole Western world. We forget it at our peril.