Classical Greece was a period during which the finest products of Greek civilization were achieved, has been defined as beginning after the victory over the Persians. Its end is marked by the appearance of Macedonian soldiers in Greece and the capitulation of the Greek cities to their semi-Greek conquerors from the north. This was the first stage in the vast program of military expansion under the Macedonian king, Alexander, which ended with his death. Macedonian expansion changed the whole face of the East: in the West events were less momentous, though in the same year as the battle of Salamis the Greeks of Syracuse held back a major attack on Sicily by the Carthaginians.

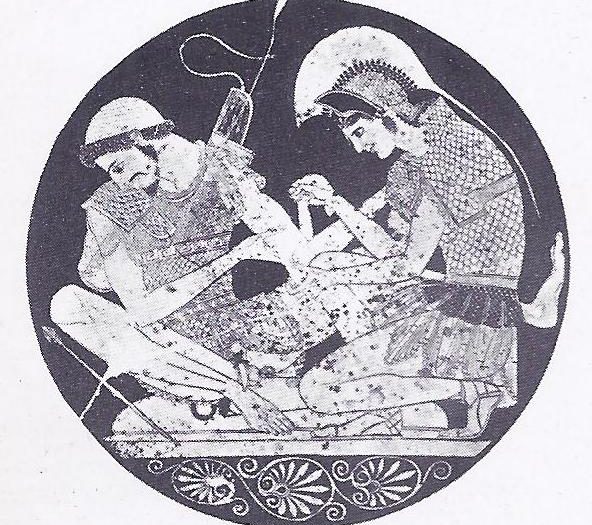

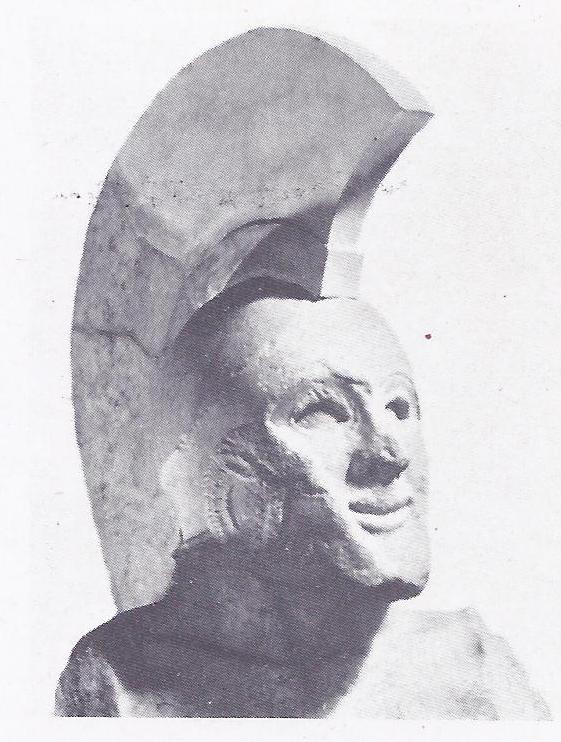

Achilles and Patroclus

The sea Victory at Salamis had been engineered by the brilliant Athenian commander, Themistocles. The land victory at Plataea, which so decisively put an end to the Persian campaign in Greece, was the work of the Peloponnesians, especially of the Spartan commander, Pausanias and his men. Pausanias was then given the task of liberating the Ionian coastal cities from Persia, but they seem to have feared his potential as a new tyrant, as did the Spartan ephors or elders and he was relieved of his mission. Athens then took up the coastal war for which she was obviously so much better suited than Sparta, organizing the islands and cities into a confederacy under Athenian leadership, the Delian League. This league was put on a formal basis, with the allies contributing ships and money for defense, but dominated as it was by Athens, it was only a question of time before it became a de acto Athenian empire.

The Ionian kinship shared by its members might have been expected to form some basis for a closer tie, but the tradition and outlook of the polis or city-state was not compatible with the idea of “nation” as we understand it today. The formation of a league was the nearest the Greeks came to national unity until the conquests of Alexander imposed a temporary unity on the Greek world. This meant that mainland Greece achieved an identity, if only through its geographical insignificance within a wider community, that of the oikoumene (the whole inhabited world).

Meanwhile, the formation of the Delian League consolidated the division of Greece into two main power blocs: the Peloponnesian League with Sparta at its head; Athens and her “empire.” These groups developed mutually hostile ideologies, based on the very different political system of Sparta and Athens.

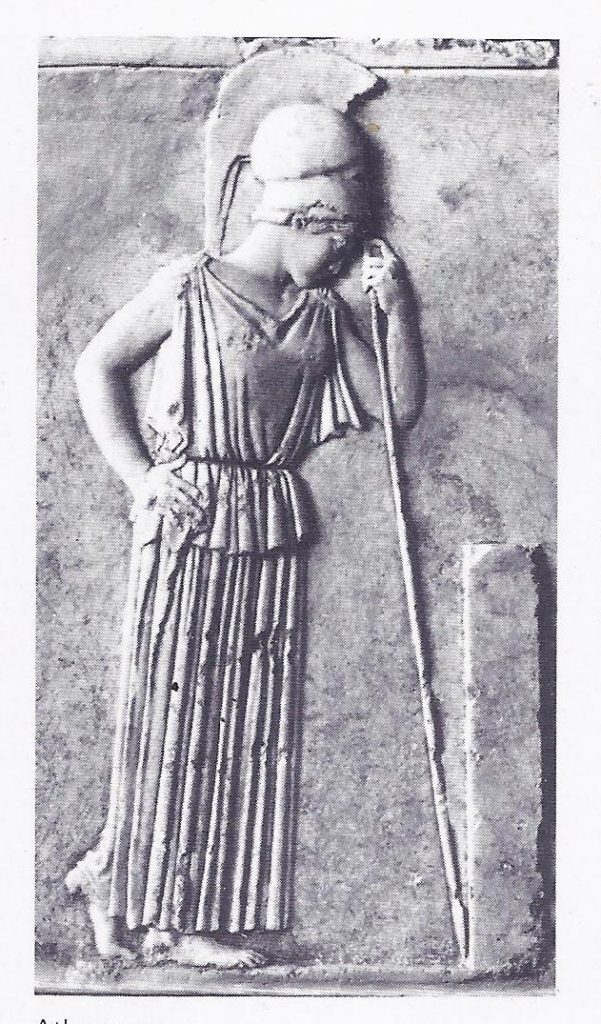

Athens

Athens at this period had achieved the ultimate in Greek democracy. It was not total democracy, as we would understand it, for a large percentage of her population were slaves, with very limited political rights, but Athens had developed a greater measure of popular representation than perhaps any other city or state has ever done.

Sparta

In contrast, Sparta was still theoretically ruled by her two kings and council of elders or ephors, below which were the citizen-élite, the perioeci and helots. Thus, oligarchy (rule of the few) was the basis of Spartan government and democracy (the power of the demos or people) in Athens.

While the Delian League was successful in holding the allies together under Athens’ leadership and while Persia remained an obvious threat and a symbolic enemy to hold the Greeks together, no confrontation with the Peloponnesian bloc occurred. Persia was decisively beaten off Salamis (Cyprus) in 451 and obliged to conclude a peace with the Greeks. The Delian League clearly had less raison d’étre now that the Persian menace had been contained, but Athens did not want to relinquish her position of dominance. The chains of empire were tightened by the establishment of colonies of Athenian citizens (cleruchies) at vital points in allied territory, guarding all important supply routes to Athens. The champion of democracy might after all be a tyrant in disguise.

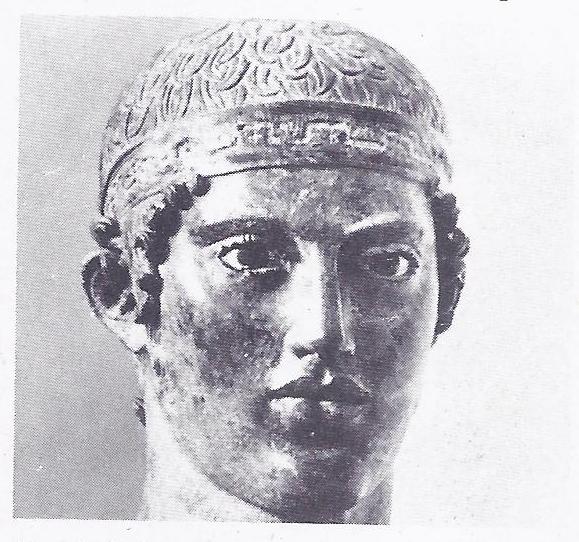

Pericles and Classical Greece

This extension of temporary military leadership to control an empire, took place under the rule of the great Pericles (470-429). The stability that lasted while Athens and her navy remained unchallenged in the Aegean enabled the arts of civilization to flourish in an unprecedented way. Athens itself was the glittering hub of intellectual and artistic activity. In the fifth century it became the centre for philosophy, drawing together philosophers from all over the Greek world who previously had had no one meeting place. While the Greeks took much of their knowledge from the East — mathematics and astronomy in particular — they developed their own methods of scientific inquiry and philosophy. The power of pure reason led to the questioning of treasured concepts about life and society; and the Sophists, who advocated such a critical use of knowledge and education, provoked a strong reaction from the more conservative elements in Athens.

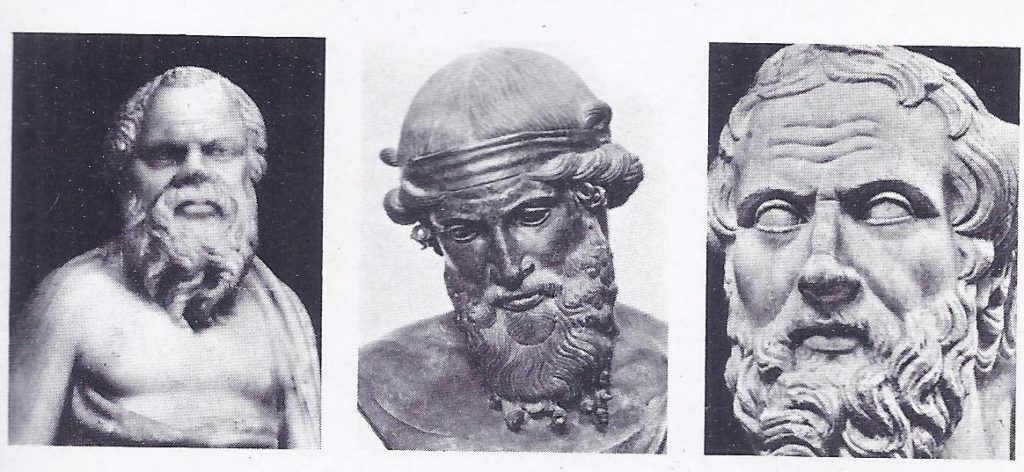

Socrates of Classical Greece

The great teacher and philosopher became notorious for his ability to criticize anything and everything, though he was in fact challenging the extreme and wayward scepticism of the Sophists. He nevertheless became a scapegoat for the excesses of the Sophists’ philosophical contortions and preferred to die rather than recant. Such was the seriousness with which philosophy was treated by both its practitioners and the people of Athens.

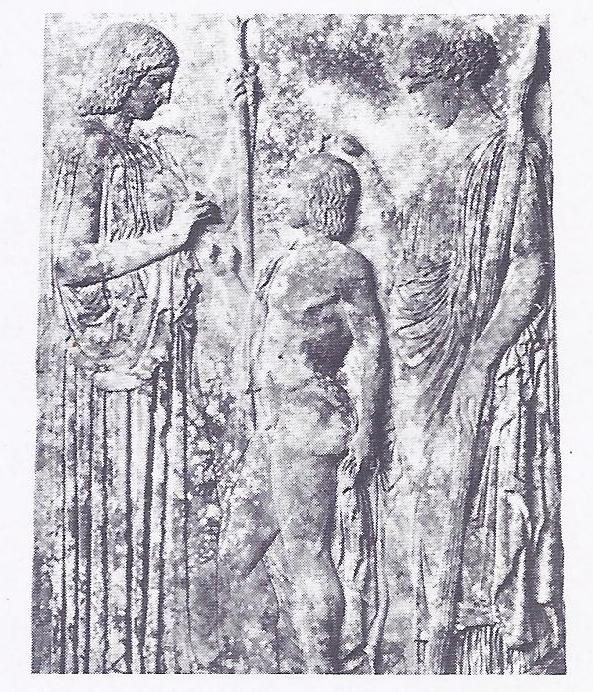

Religion and Temples of Classical greece

Philosophy did not entirely dispense with the gods, who were still an integral part of Greek culture everywhere. Since religion centered on the performance of the cult of a particular god or goddess, ceremonies mattered much more than doctrine, so philosophy was not a radical alternative. Religion was essentially bound up with the life of the polis and large sums were spent on erecting temples to tutelary deities. These magnificent temples offered perfect opportunities for the expression of the Greek artistic genius; the architecture and sculpture of this period has haunted European civilization from that time to the present day.

Greek Drama during Classical Greece

The Greeks of this period also produced remarkable new developments in literary form. The creation of the theatre, or more specifically, the creation of a permanent repertory of written plays, dates from the birth of Attic tragedy in the incomparable works of Aeschylus (525-456), written at the time of the struggle with Persia. Sophocles (497-406) and Euripides (480-406) continued the tradition of Attic drama and Aristophanes’ (444-380) delightful plays, full of wit and sharp digs at the politicians, developed the new art of comedy.

Plato

Socrates’ unwritten teachings were put into elegant and powerful words by the philosopher and writer Plato. His works, models of lucridity and style, include two emulating and fundamental treatments of political theory, The Republic and The Laws.

The Athenian search for truth was a passionate and pragmatic. Plato’s works examined the real world of the Greek polis and formulated more or less ideal solutions to the problems of city life, but he even tried out his theories in a practical experiment. The tyrant Dionysus II of Syracuse was at his own request carefully educated by Plato to be the “ideal ruler,” the embodiment of Plato’s wise philosopher-king. The experiment failed, as Dionysus proved too easily distracted by human pleasures, but it shows the extraordinary status of philosophy in Greek society.

Herodotus and Thucydides

The politics of the Periclean age profoundly influenced historical as well as other literary forms. Herodotus of Halicarnassus, proverbially “the father of history,” produced a study of the Persian Wars that initiated true historical analysis where before only the uncritical tabulation of chronicles had existed. Athens’ tight hold on the Aegean and the exacerbation of her relations with Sparta came to a head in 431 and war broke out. The ensuing conflict brought down the Athenian empire. Such a momentous event caused the historian Thucydides to ponder on the reasons for such a calamity. His work on the Peloponnesian War and the destruction of Athens’ greatness, analyzing one of the most exciting and disturbing periods of history, is one of the most penetrating and skillful pieces of historical writing ever produced.

Victorious Sparta

The Peloponnesian War left Sparta Victorious and the Athenian navy and defenses were destroyed. Sparta was to enjoy only a brief period of hegemony in Greece. The war was concluded in 404: by 401 Sparta was embroiled with the Persians and in Greece, was faced with an attack from her allies who were dissatisfied with her treatment of them. War followed.

Thebes

The city of Thebes, which had developed a highly efficient army under the brilliant general Epaminondas, emerged as Victor from the struggle, destroying the Spartan army at Leuctra in 371. Victory brought with it leadership of the other Greek cities, but Thebes’ domination was resented just as Sparta’s (anal Athens’) had been. The pattern of intermittent wars, the shattering of one city’s armed power to permit the emergence of another to dominate a federation of cities, was ominous in its repetition.

Clearly the economic and political decline of Greece was a reality. The situation of the Greek cities could conceivably be exploited by a number of external powers — the Carthaginians’ sphere of influence dangerously overlapped the Greek settlements in the western Mediterranean and Persian ambitions might flourish again in the East. As it happened, the resolution of Greece’s discord and decline came firmly from a direction that few people could have expected at the time.

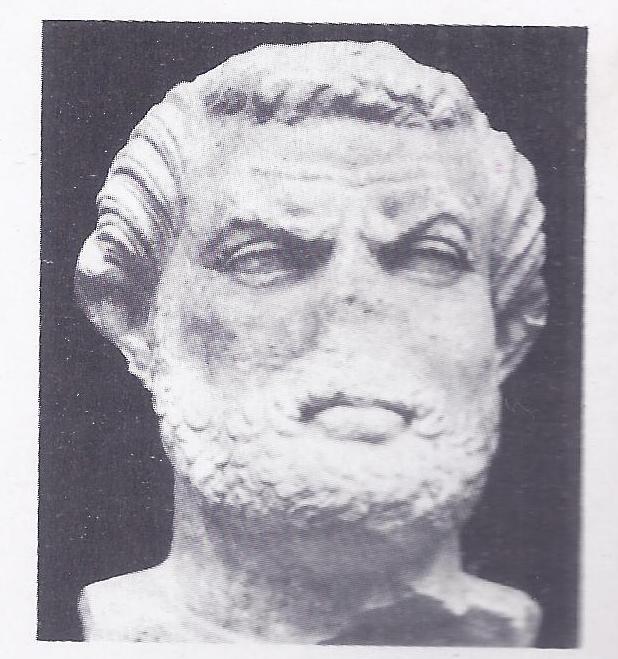

Philip of Macedonia

To the north of Greece proper, lay the kingdom of Macedonia, peopled by “barbarians” in Greek terms, though the ruling family was recognized as Greek. Feudal wars and local quarrels with the Illyrians were the Macedonians’ traditional occupations but a strong state emerged under King Philip II. He had spent some time as a hostage in Thebes and had absorbed knowledge of the Greek way of life and more important, knowledge of military procedure from the famous Theban troops. Under his rule the military potential of Macedonia was developed and organized.

The new power of Macedonia grew visibly as Philip intervened in Thessaly and had himself elected as military commander. The presence of a strong state to the north produced various reactions among the Greeks. One line of thought, voiced by the orator Demosthenes, warned against Philip as a threat to the “liberty of Greece.” The orator Isocrates championed the idea of Philip as the strong leader who was needed to unite the Greeks and lead them out of the morass of their political and military conflicts. The choice of the Greeks hardly mattered anyway. Philip was obviously aiming at the leadership of Greece and there was no effective way to limit his designs. Military conflict with the Macedonians followed and the last remaining Greek army of consequence, that of Thebes, was defeated together with Athenian soldiers at Chaeronea in 338. Philip became hegemon, or ruler, of yet another Greek league, comprising all the major Greek cities except Sparta, whose absence hardly mattered since she was no longer powerful.

Alexander

At the battle of Chaeronea, Philip’s son Alexander played a decisive role in the victory and proved himself a great military commander. His father dreamed of taking final revenge against the Persians on their own ground. Alexander inherited this ambition and how he achieved this, is great subject matter in history.