Alcibiades was the nephew of Pericles. As well as being rich and handsome, he was amusing, clever, insolent and unreliable. He was about twenty when Socrates saved his life at Potidaea in the first year of the Peloponnesian War (432). He fought in other battles and also found time to lead a gay life in Athens, to talk to Socrates and to race chariots in the Olympic Games. It was not till after the death of Cleon that he became a leading politician and general. It may seem surprising that the place of a tanner should have been taken by …

Read More »Hellenes – Ancient Greek Mythology

Socrates

Socrates was short, ugly and brave. He served as a hoplite in the Peloponnesian war and on one occasion saved the life of a rich and handsome young recruit. It was the proper thing to do of course, but one’s admiration is tinged with regret, for the recruit whom Socrates rescued was Alcibiades. The time was now approaching when many Athenians would curse that name. The strange thing is that, throughout these first ten years of the Peloponnesian War and the worse ones which were to follow, one of the wisest and most lovable men who has ever lived was …

Read More »Peace

Not everyone approved of this policy. The country people, whose farms were being devastated every year by the invading Spartans, were ready for peace. So was Aristophanes. In 424 he won first prize with the Knights, a comedy in which he himself played the part of Cleon. So savagely satirical were the lines he had written for this character that no one dared make him a mask to wear. So he smeared his face with red juice and went on the stage without a mask. Cleon for all his power, could not retaliate. In the following year (423) Cleon went …

Read More »Cleon the Tanner

Cruelty showed itself only two years after Pericles was dead. In 428, after the usual spring invasion by the Spartans and before the Olympic games, which were being held as usual, Lesbos had revolted. The Spartans had promised to help the Lesbians and in the following year their fleet at last arrived — a week too late. Mytilene, the capital of the island had already surrendered to the Athenians. The Athenian Assembly now had the people of Mytilene at their mercy. They voted that every man should be put to death, the women and children enslaved. A trireme was sent …

Read More »Pericles Dies

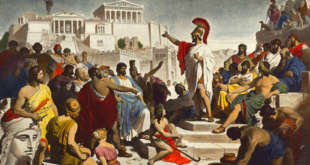

Before Pericles dies, the morale in Athens was low. For the second year in succession the Spartans had been allowed to lay waste to the countryside. This alone would have embittered public opinion. Now, in addition, there was the plague. People began to talk about suing for peace. Criticism of Pericles, already sharp enough in the previous year, now reached a point where it had to be answered. Pericles tries to appeal to the patriotism of the Assembly and then to their common sense. He said: “Let us be frank. What we have established is a kind of dictatorship. Perhaps …

Read More »Hippocrates and Disease

In Hippocrates’ time, if death was the end, what could be done to stave it off? Deprived of what we would now call the comforts of religion, could the Athenian at least rely on an efficient medical service? Herodotus describes a doctor called Democedes who (in the 6th cent.) was hired by three states in turn – Aegina, Athens and Samos – each offering a higher salary than the last. So there may have been some sort of state medical service. Army doctors appear as early as “the Trojan War and a wounded Athenian in the Peloponnesian War would be …

Read More »Athenian Death

Athenian deaths were now a shadow of the past. When Aeschylus, in his play, the Persians, thanked the gods for the victory of Salamis, he was writing for an audience who still had religious faith, but in the years of prosperity which followed, although bigger statues of the gods and more splendid temples went on being put up, piety did not keep pace. On the contrary, the philosophers argued about the gods, Euripides made jokes about them in his plays and the ordinary man bothered much less about them, now that life had become so much safer and more prosperous. …

Read More »The Peloponnesian War Begins

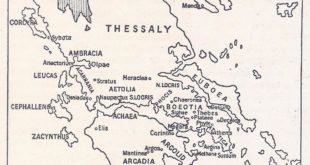

The Peloponnesian War began because Pericles was running our of time. In the first place Athens insisted on backing Corcyra in a quarrel with Corinth (435). Corcyra was a Corinthian colony and the mother-city resented interference in the dispute, particularly since it brought Athenian ships round to the western coast of Greece where they could interfere with the trade route to southern Italy. The second trouble-centre was also a Corinthian colony, though a tribute paying member of the Athenian Empire — Potidaea in Thrace. Now that Athens saw trouble brewing with Corinth she insisted (432) that Potidaea should get rid of …

Read More »Why Did Athens Fight Sparta

In spite of the fact that they had fought as allies against Persia, Sparta and Athens did not like each other any better when the war was over. In 478, when the Athenians started to rebuild their fortifications, Sparta objected and Themistocles had to arrange for negotiations to drag on until the walls were finished. There followed the Spartan failure to lead the Ionians against Persia, while Athens founded the Delian League. In 464 the long dreaded revolt of the Helots began, following an earthquake which had laid the town of Sparta in ruins. After some savage fighting the Helots …

Read More »Thucydides

When Herodotus read his history in public, it is said that a youth called Thucydides was so moved that he burst into tears. Herodotus congratulated the young man’s father upon having so appreciative a son. Thucydides grew to be a rich man. He owned gold mines in Thrace. During the Peloponnesian War he commanded a squadron of Athenian ships but, having failed to accomplish the mission assigned to him, he went into exile (424). He used his enforced leisure to work on a history of the war which he had planned. He only reached 411 (the War went on till 404), …

Read More »