Athenian deaths were now a shadow of the past. When Aeschylus, in his play, the Persians, thanked the gods for the victory of Salamis, he was writing for an audience who still had religious faith, but in the years of prosperity which followed, although bigger statues of the gods and more splendid temples went on being put up, piety did not keep pace. On the contrary, the philosophers argued about the gods, Euripides made jokes about them in his plays and the ordinary man bothered much less about them, now that life had become so much safer and more prosperous. Women, who on the whole had a thinner time, perhaps worshipped more sincerely. There were of course plenty of religious festivals (e.g., the Panathenaea and the Great Dionysia) and plenty of religious customs (e.g., after dinner men would each pour some wine out of their cups in honour of Zeus) and it must also be remembered how difficult it is in any age to find out people’s feelings about religion. This much, however, can be said with certainty: the Athenians who embarked upon the Peloponnesian War were not a pious people.

How then did they face Athenian death? Not cheerfully. Even the faith of older generations could not help them. The aged Charon, so ran the story, ferried you across the river Styx to Hades, where you lived out a shadowy, unhappy existence till the end of time. Charon was now a joke; but the dreaded, shadowy eternity remained. No one, except perhaps the select few who took part in the secret Eleusinian Mysteries, had any hope to offer. So the Athenian deaths generally meant they burned their dead, put the ashes in an urn made of pottery, buried it and placed some food for the departed spirit on the grave. Later they put up a gravestone and that was that.

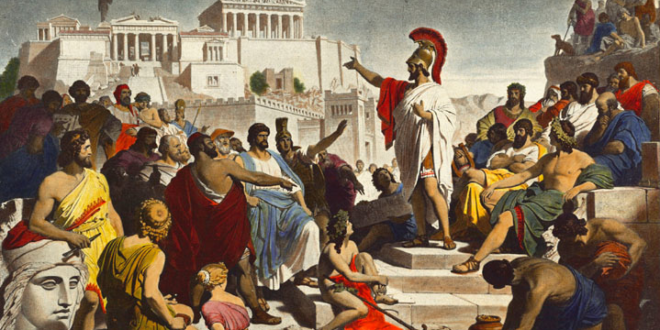

An Athenian death for men who fell in battle meant they were given a state funeral and a speech was made. In the late autumn of 431, when the first casualties of the Peloponnesian War were buried, Pericles made the speech. Since he could not offer the mourners any consolation in the form of hope for a life after death, he devoted himself to praise of Athens and so honoured the Athenian death.

He explained how her democratic government favoured the many instead of the few and her laws afforded equal justice to all. Poverty he said, need not be a bar to advancement; on the contrary, every citizen was expected to be a judge of public affairs. Discussion was regarded as an essential preliminary to action (in some countries, he hinted, obviously thinking of Sparta, discussion was frowned upon).

Again tilting at Sparta, where foreigners were not welcome, he said that Athens was open to all — foreigners might go everywhere and see everything, even if they occasionally abused the privilege. Athenian education, too, was superior to Spartan; the Spartans imposed a rigorous discipline from childhood, while Athenians grew up in freedom but became every bit as brave.

“In short” he went on (and this is perhaps the most famous passage of the speech, as recorded by Thucydides), “I say that as a city we are the school of Hellas; and I doubt if the world can produce a man, who, where he has only himself to depend upon, is equal to so many emergencies and graced by so happy a versatility as the Athenian. . . . I would have you day by day fix your eyes upon the greatness of Athens, until you become her lovers.”

Gradually the mourners were brought to realise the many-sided glory of the city for which their loved ones had died. Men who died for such a city would be famous far beyond its borders. Their deeds would be remembered, wherever brave deeds were remembered. “For” said Pericles, “heroes have the whole world for their tomb.”

Thucydides is a splendid historian but he does not always tell us all we want to know. How did the mourners react to this speech for the Athenian death? Nobody knows. What we do know is that with all his fine phrases Pericles had not yet spoken one word of real comfort. He had two sons of his own; but he did not say: “I know how you feel.” He realised, however, that something more intimate was expected of him, so he said that those fathers who were young enough should beget more children in order to help them forget those they had lost and to help the state.

A word to the women whose husbands had been killed? Just this — “Don’t get yourself talked about among men.” Then, with an assurance that the children of the fallen would be brought up at the public expense, the speech ended.

Charon’s old boat must have creaked that night, so laden with honour were his sad ghostly passengers, but as the winter sun set over Athens and night covered her splendour there were many who went uncomforted to bed.