Baghdad founded and became the centre of Islamic learning and culture.

England in the tenth century

As a soldier, Alfred, rightly called the Great, saved his nation; as a legislator, he established the concept of a nationwide law for all the English; as a patron, he not only launched an educational revival, but himself translated Boethius’, On the Consolation of Philosophy and sponsored the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a major historical source for another two centuries. Although he had consolidated the existence of an English nation, Alfred had been able only to contain the threat of the Danes. Vast territories in the north and east of England remained independent of the kings of Wessex and their client-kingdom of English Mercia.

Alfred’s son, Edward the Elder, reigned conjointly with his sister Aethelflaed, the Lady of Mercia. At her death the kingdom was united. During this period, the English, basing their defense on the series of fortified towns begun by Alfred, made headway against the incursions of the Scandinavian kingdoms that surrounded them. Even in the midst of a struggle for survival, Alfred had planned for the future. His fortified boroughs provided not only military bases, but the foci of local administration and trade. Edward extended the military fortifications, but an aggressive counterattack against England’s enemies did not come until the reign of Athelstan (924-39).

Brother-in-law of the Carolingian Charles the Simple of France, of Hugh Capet, the greatest man in the French kingdom and of the German Emperor Otto I, Athelstan mightily defended his position at home. He inflicted the crushing defeat of Brunanburh on the combined forces of the Scots, Irish, Norse and Welsh — a fight commemorated in one of the great epic poems of Old English. The glitter of the medieval English monarchy was at its most dazzling in the subsequent reign of Edgar; at his coronation in 973, eight client-kings are said to have paid homage.

English literature appears

It was in the tenth century that the potentialities of the Old English language – ancestor of the parlance used by Chaucer and Malory – first became apparent. The triumphant song of Brunanburh is paralleled at the end of the century, by the tragic and heroic poem on the defeat of the Earl Byrthnoth, by the Danes, at the Battle of Maldon in 991. Such verse was in the well-established heroic tradition of Beowulf, but in the tenth century, English found its primary power as a means of expression in prose. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle itself was of course written in English, while the Church employed English prose not only in its preaching, but also in magnificent homilies, lives of the saints and translations of parts of the Bible.

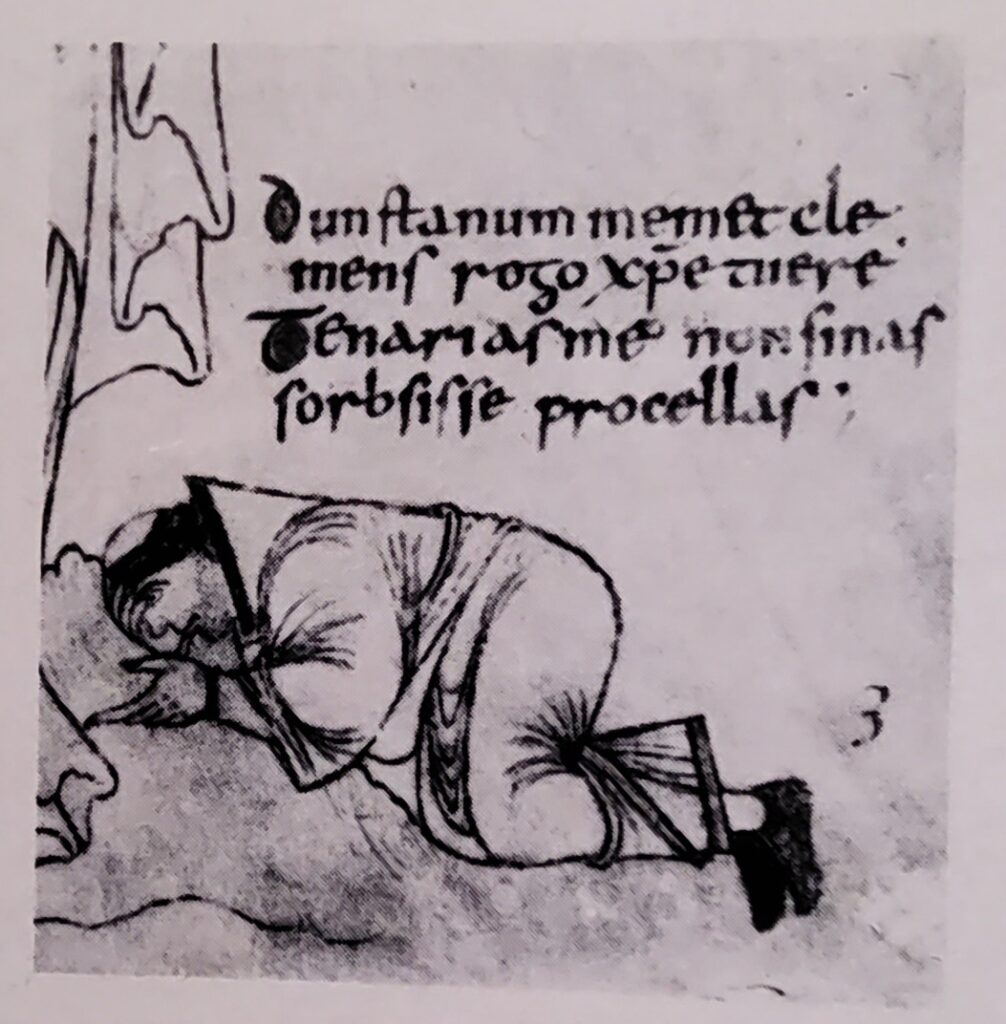

Among these lives of the saints was one of St. Dunstan, Abbot of Glastonbury, Archbishop of Canterbury, close confidant of King Edgar and church reformer. It was through Dunstan, that the great Continental movement in Church and monastic reform, launched by the founding of the Abbey of Cluny in 910, reached England. During a short stay in Flanders in the middle of the century, Dunstan had seen

the work of the reformed Benedictines first hand and returned to England in order to transform the unregenerate Church there. Alas, in the last twenty years of the century, the renewed impetus of Danish invasions plunged the country once again, into a dark night of disruption and despair. After the humiliating reign of Aethelred the Redeless — in which neither king nor people displayed the confidence of their ancestors – Britain was only to be saved, by the enlightened rule of the great Danish king Canute, early in the eleventh century.

The Arab World

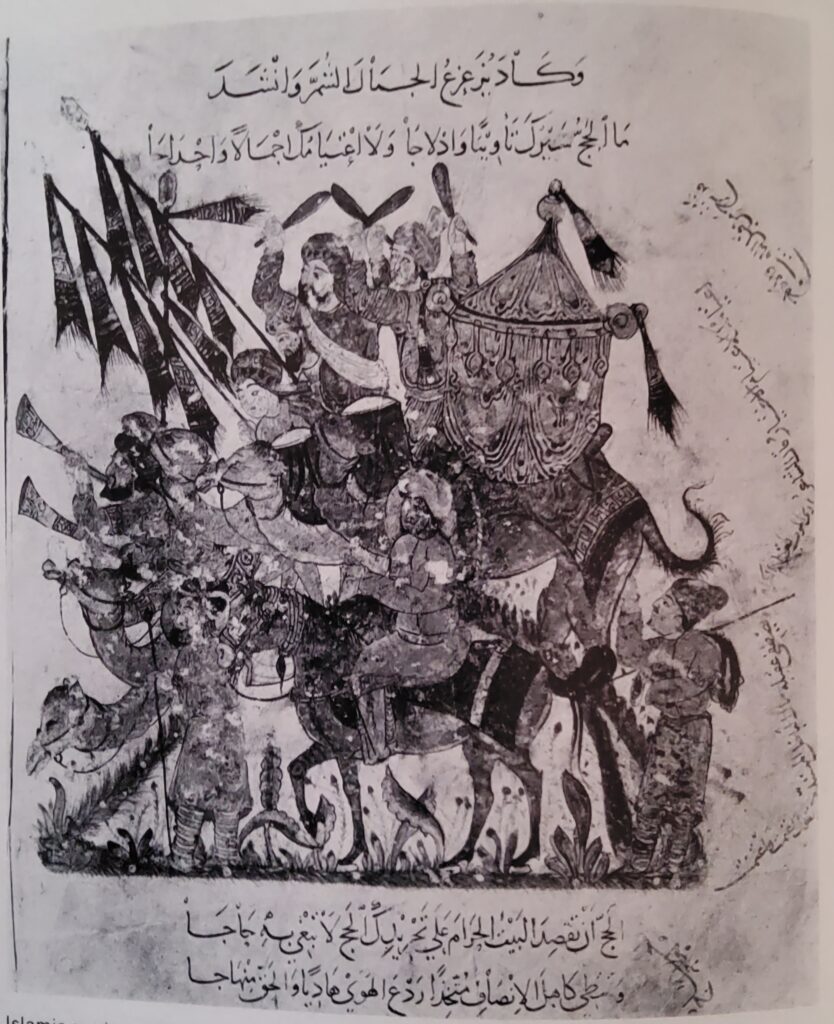

Just as the armies of Islam had profited from the religious discontent of the great empires it conquered, so religion provided the pretext for the overthrow of the first Moslem dynasty. The population of eastern Persia, which had accepted the new faith, nevertheless felt aggrieved and discriminated against. The Persians claimed that they did not enjoy the full exemption from taxation that was their right as believers; more importantly, they resented the alien rule of the distant regime at Damascus. When the central government ignored their protests, the local nobility of Khorasan, with the aid of discontented Arab colonists, rose against the Umayyads. Abu al Abbas, a descendant of Mohammed, was leader of this revolt. By 750, Abu al Abbas had founded his own dynasty, the Abbasids and seen all but one of the Umayyad family perish in a sea of r blood. Under the Abbasids, the Persian influence in Islam became increasingly marked; within a generation, the Caliphs had founded a new Capital at Baghdad, on the banks of the Tigris, which was to become one of the greatest cities in the world.

It was at this time, that the great collection of stories known as the Arabian Nights, first began to be assembled. Despite the Indian origin of many of the tales, they are a monument to the glories of the Arabic language and to the golden age of the Abbasid caliphate under the great Harun al Rashid or Aaron the Upright (d. 809) and his son Al Ma’mum (d. 833). During their reigns, the process of Persianization reached its highwater mark. In addition, under the impulse of Syrian Christian scholars, the Arabs began to discover the treasures of classical Greek philosophy and science, with incalculable consequences for the future of civilization.

Greek influence

Al Ma’mun founded a school at Baghdad for the translation of the classics of Greek philosophy and science. The impact was tremendous. Not only was Arab scientific thought advanced, but the tool of Aristotelian dialectic was applied to all fields of thought, including theology. Some scholars aimed to reconcile Greek with Islamic thought, but a rival school opposed such liberalizing tendencies — a similar controversy was to arise in twelfuh-century Europe. Greek theory also influenced music and the scale used in Arab music, shows remarkable similarities to that postulated in ancient Greek treaties. Here, an equally important influence was that of Persia. Traditionalists opposed the seductions of the “romantic” Persian style on the gounds that it would corrupt the solemn and serene music prescribed by Mohammed; but despite opposition from famous musicians, the Persian style gained ground. Its music became one of the chief glories of Islamic civilization and the esteem in which it was held, was reflected in the fame of the great musicians, which sometimes rivaled that of their princes.

The profound impact of the Arab conquests, from the frontiers of China’s T’ang empire to Spain, is reflected in the spread of the religion of Islam today. During the Middle Ages, the whole of this vast area was linked by a common religion, a common language and common coinage. It was traversed by heavily frequented trade and pilgrim routes. Like the world of Christendom, it had many vital shared interests and beliefs. The political divisions that soon arose, while provoking more than their share of wars, did not seriously impede the flow of a common culture.

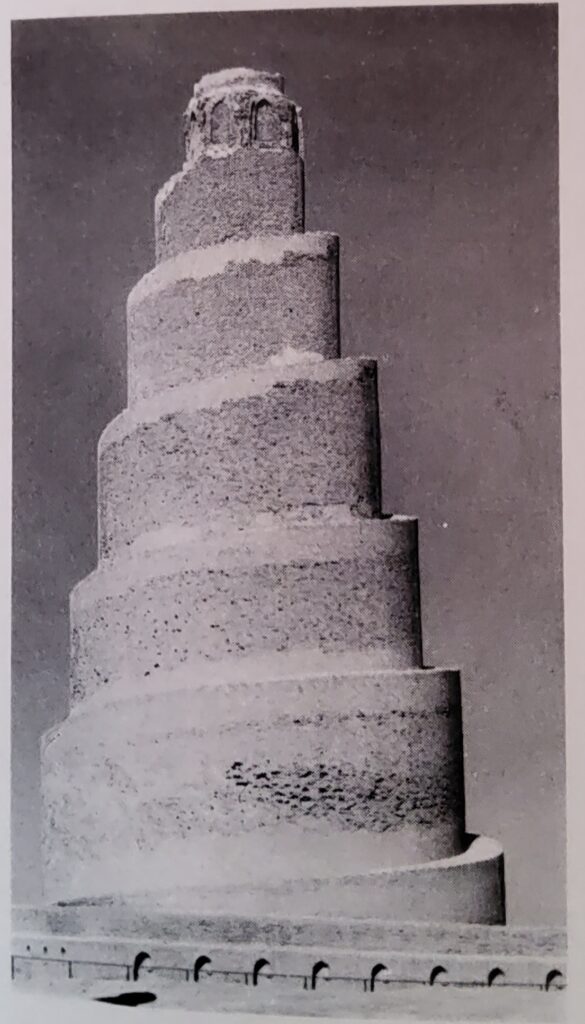

After the establishment of the Umayyad caliphates of Spain in 756, the unity of Islam was further broken. The Aghlabid emirs on the North African coast were plundering the Christian shipping of the western Mediterranean and sending raiding parties far up the rivers of mainland Europe. Farther west, in modern Morocco, a rival Shiite caliphate had arisen and for the last half of the ninth century the emirs of Egypt too, asserted their independence. The break-up of the vast Arab Empire was hastened by the fact that the Caliphs at Baghdad, unable to raise an army from the now settled populations of their flourishing empire, had to recruit Turkish mercenaries. After an attempt to weaken the influence of this Praetorian guard by establishing a new capital at Sammarra, the Caliphs were forced to return to Baghdad. As the tenth century progressed, their effective influence progressively waned. In Persia a new national dynasty, the Samanids, revived Persian culture; in Egypt, the Fatimid caliphate founded a brilliant independent civilization which survived until the twelfth century; and in Spain, the court of Cordova was legendary in Christendom as well as in Islam.

Spain – the Legacy of the Visigoths

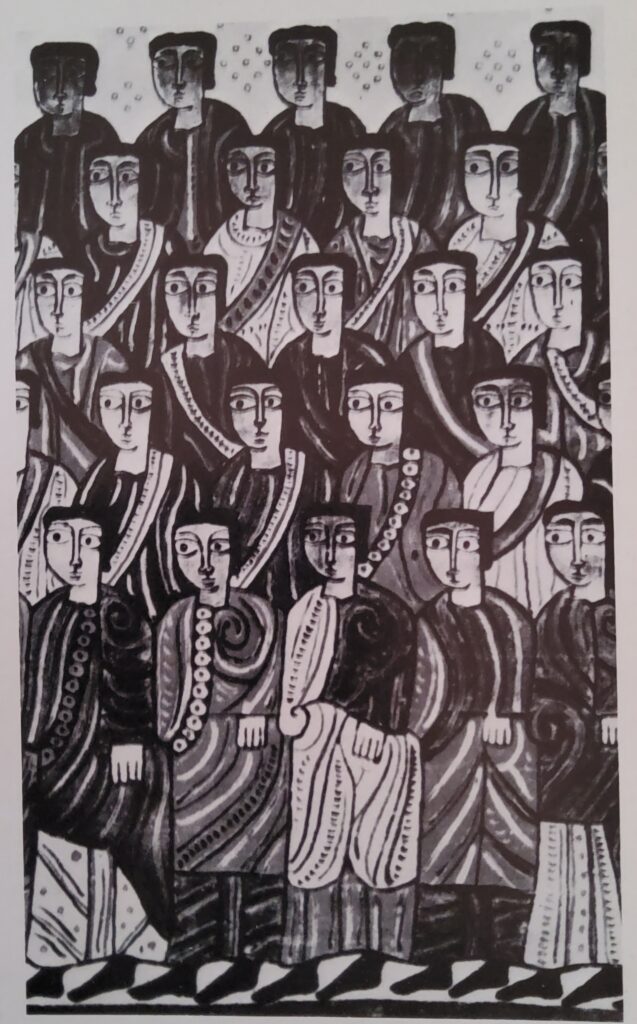

By the eighth century, the Spanish Visigoths had guaranteed the triumph of Catholicism over Arianism, given the Spanish monarchy a characteristic and continuing controlling interest in ecclesiastical affairs; presided over the birth of a highly individual and brilliant culture. Spanish culture was eclectic in its inspiration, drawing on barbarian and classical motifs, on the art of Byzantium and in the field of scholarship, on the tradition of the long-established, though persecuted, Jewish community. The very liturgy of the Church was a unique blend of Roman, Arian and Byzantine Eastern element.

Archbishop Isidore of Seville, of mixed Spanish and Byzantine ancestry, was one of the most remarkable figures in the Europe of the Dark Ages. His writings continued to exert an immense iInfluence through the Middle Ages. In jewelry, sculpture, book illumination and architecture, Visigothic Spain displayed a considerable and refined creative talent. One of the most interesting surviving monuments is the church of S. Juan de Banos, dedicated by the first Catholic king, Recceswinth. The Visigoths left a lasting imprint on Christian Spain. The much-reduced kingdoms of Asturias and Galicia, on the northern coast, felt themselves the heirs of the Visigothic tradition and the long delayed counterattack of the Christian kingdoms, conducted by the Visigoths’ successors, Castile, Leon, Navarre and Aragon, was thought of by the Spaniards as the Reconquest. Moslem rule in Spain began with the landing of a predominantly Berber army under the leadership of the Arab Tarik at Gibraltar in 711. The new rulers recognized the Caliph at Damascus; but in 756 the sole survivor of the Umayyad family, expelled from Damascus by the Abbasids, established himself at Cordova. His family, of whom the greatest ruler was Abd al-Rahman III (912-61), the man who brought Islamic civilization in the peninsula to its highest peak, ruled for another 250 years.