Cluny, the Greatest Benedictine Abbey in Europe, was founded in 910. After the reign of the great Abd al-Rahman III, Islamic Spain was increasingly subject to internal division and the overthrow of the Cordovan Caliphate in 1013, allowed the Christians to capture the great city of Toledo. The Spanish Arabs now called on the newly converted and fanatical North African Berber tribes known as the Almoravides. By the beginning of the twelfth century, these allies, whose empire was based in Morocco, were in control of Islamic Spain. Within seventy years, they in their turn, fell to the still more puritanical sect of the Almohades. In 1195, the Almohades inflicted a crushing defeat on the armies of Alfonso VIII of Castile, but this was more than reversed by the great victory of the united kingdoms of Castile, Leon, Navarre and Aragon on the field of Las Novas de Tolosa in 1212.

Islam Fails

After that defeat, Islam never recovered its old power in Spain. Under the caliphate of Cordova, both the industry of the Moorish invaders, their religious toleration of the conquered Christians and the formerly persecuted Jews, contributed essentially to the great cultural flowering of the period. The Mozarabes, Christians who retained their faith on the payment of annual dues, were allowed their own places of worship. Throughout the Islamic period, save for a few years before its recapture, the city of Toledo kept itsncathedral, its archbishop and its liturgy. Despite the strict religious principles of the twelfth-century Moroccan rulers and the subsequent flight of numerous Mozerabes to the Chnistian kingdoms of the north, the cultural traditions of earlier ages was strong. It was the works of men like Avempace (d. 1138) who drew on the Aristotelian commentaries of the tenth-century Al Farabi of Damascus and above all, his great follower Averroes of Cordova (1126-98), who contributed so essentially to the intellectual ferment of twelfth-century Europe.

Church reform in Europe during the tenth-century

The ninth century was a period of fierce rivalry for the control of central authority, of cynical and brutal struggle by lesser potentates for independence from that authority and of invasions from outside Europe. Yet gradually, if only by force of custom, lay society was evolving commonly accepted principles of organization and Iegtimacy that were slowly to gain — during later generations — evergrowing effectiveness.

In terms of power, the ninth century was a secular period. The immense power that the Church was to exercise in European society was a thing of the future and as the tenth century opened the Church, in all its organs, was at one of its lowest points. Many of Europe’s greatest bishops were, in effect, the hereditary fiefs of the local great family. If the family did not actually occupy the see, it appointed its own nominees as a matter of course. In other sees, the appointments were made by the king. The bishops themselves shared the ambitions and morals of their turbulent class and were also expected to pay a considerable sum of money to their patrons on entering their office. In feudal terms, this was construed as the “relief” that any heir paid his overlord on taking up his inheritance, to clear him of the outstanding obligations of his predecessor and as recognition that he held the fief from a higher power.

Sins of Simony

In ecclesiastical terms such payments amounted to the sin of “simony.” The name was derived — from the Samaritan sorcerer, Simon Magus, who, according to the account in the Acts of the Apostles, attempted to buy spiritual power from Chnist’s apostles. In practical terms, simony produced a chain-reaction: the bishop, who had paid a heavy fee to enter his see, recouped his payment by charging for the rights of ordination to his inferiors and they in their turn charged the faithful, for the very benefits of religion. It is not hard to understand the outrage of ecclesiastical reformers, but to the kings and magnates of early medieval Europe, it seemed totally reasonable that bishops, who after all were vast landowners, should accept the same obligations as their lay colleagues. Not only were the bishops subject to the feudal ceremony for receiving their lands from their lord, but by the ninth century, the king was also investing them with the ring and staff, the symbols of their spiritual power. Thus the regular offices of the Church had become almost indistinguishable from the great secular estates which they often equalled in wealth. The secularization of Church property extended to the lowest levels. The parish church was usually the personal property of the local landowner who disposed of it at will; often the priests — most of whom were married, clerical celibacy being a thing of the future, treated their parishes as hereditary holdings and might well enrich their own families by granting Church lands to laymen in return for payment.

Conditions of Monastic life

Conditions were little better in the monasteries, which springing from the great movement initiated by St. Benedict in the sixth century, were the heirs to a great tradition of piety and retreat from the world. During the course of the centuries, they had grown rich through large endowments which they had received from pious benefactors. In their turn, they became objects of the ambitions of the lay aristocracy. It was not uncommon for the richer monasterics to be controlled by absentee lay abbots who unscrupulously engrossed the revenue of the house to their own uses. In other cases, the monks themselves, might form into a college of canons, forsaking their monastic vows and the ideals of the life of communal poverty, in order to live off the income of the monastery in their own houses, complete with wives and families.

When matters had reached this pass, the very nature of the Benedictine Rule contributed to increase rather than mitigate the decline. St. Benedict’s Rule had been merely a rule of conduct not dependent on a central organization. In the past, the autonomy of each monastery in this cell-like structure had been an element of strength and the monasteries’ adherence to the Rule had been ensured by visitations from the local bishop. However, in a world where the episcopate was itself in dire need of reform, European monasticism was without a guardian. There are many recorded instances from both the ninth and tenth centuries and indeed later, of reforming abbots being maltreated and expelled by the inmates of the house they had come to purge. The respect for the ideals that monasticism had proclaimed, was not dead and pious laymen and ecclesiastics were to be found. The Church though, as an organization was desperately in need of leadership from outside to help in putting its own house in order. In the eleventh century, the very papacy itself was to require the strong hand of a pious emperor for its reform.

Monastic Reform

In the early years of the tenth century, however, the movement for monastic reform, so important to the Church as a whole, owed its effective beginning to the initiative of a lay ruler. In 910, Duke William I of Aquitaine, called the Pious, founded a monastery at Cluny, in the French province of Burgundy. It is possible that this initiative, might have produced few lasting results had it not been for the forceful personality of the second abbot, Odo. During his reign, from 927 to 942, Odo made Cluny the leader of the movement of reform that was gathering strength everywhere in; Europe. However, Duke William had given the new house one priceless advantage, which made Cluny a truly remarkable institution at the time of its foundation. The Duke surrendered, for himself and his heirs, all rights that he had as founder.

Thus from the outset, Cluny was freed from the dangerous ties to the lay aristocracy that had brought disaster to so many monasteries in the past. Abbot Odo added to this, another great guarantee of independence when he won exemption, both for Cluny and her sister houses — both present and future — from episcopal visitation. On this basis and that of his own immense reputation, Odo was able to begin a process which, under the autocratic rule of a great line of abbots, was to produce what was in effect a new monastic order. Odo himself was summoned by Hugh the Great, the virtual ruler of France, to reform the house of Fleury on the Loire and this was to become in its turn, a major centre of reform.

At the very end of the tenth century, began the rule of Abbot Adilo (994-1048). Under him and his successor Hugh (1049-1109), Cluny reached the highwater mark of its influence and wealth. The strength of the reform rested not only on the qualities of these great abbots, but more important still, on the tight organization whereby Cluny itself retained control over all the houses that accepted its reforming agents, or were founded under its auspices. Every year the priors of the Cluniac houses, of which there were some two hundred by the late eleventh century, met at Cluny under the presidency of the abbot. The effect of this annual convocation was carried through by a well-administered system of visitation, the houses of the order being divided into ten provinces.

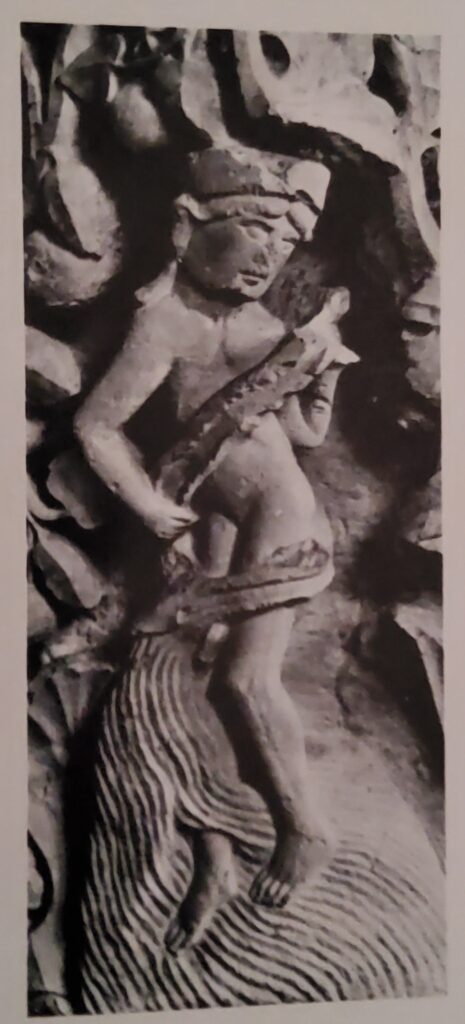

Thus within two centuries, the prestige of European monasticism, once so low, was immense and its leaders were men of considerable influence, both in the Church and in lay affairs. It is perhaps not surprising then, that an organization as powerful as Cluny began, in its turn, to lose touch with the spirit of the reform. The abbey building of Cluny proclaimed its great wealth; the luxuriant carvings and gold and jeweled church ornaments might be regarded as celebrating the glory of God, but by the critics of Cluny, they were looked upon as a betrayal of the monastic vows of poverty. Thus in the early eleventh century, Cluny itself was to give birth to a movement devoted to another great reform of European monasticism.

The Saxon kings of Germany

As the body of the Church gained in vigour through the reform of monasticism, the greatest power in medieval Europe, the German empire, was also gathering its strength. Its true founder is generally recognized as being Henry I, known as Henry the Fowler, the Duke of Saxony, who was elected to succeed Conrad I in 919.

During his reign, Henry succeeded in recovering the duchy of Lothairingia, part of the old central kingdom, from its allegiance to France. Then, after having been forced for five years to pay tribute, Henry defeated the Magyars at the battle of Riade in 933. In addition, he extended the northern frontiers of Germany at the expense of the pagan Wends in Brandenburg and he took measures to protect his frontiers with fortified strong points and by introducing reforms into the training of his Saxon army. Internally he did nothing to hamper the great power of the old duchies, ruling what might almost be described as a federal state. Nevertheless, he secured the recognition of his son, Otto I, as his successor. In 936 Otto I became King of Germany. His position was, however, contested at first by hig brother Duke Henry of Bavaria, while Eberhard of Franconia also rose in rebelion. The new king successfully met the challenge and survived another wave of rebellion in the 950s in which his son was involved. In 951 he assumed the title of King of Lombardy and eleven years later, he was to be e crowned Emperor.

Otto is often regarded as the true founder of the medieval German Empire. The title had been in abeyance for fifty years when he revived it. Certainly the Ottonian empire was essentially different from its Carolingian predecessor. Geographically, it was virtually , coterminous with the kingdom of Germany, though its rulers still retained ambitions in Italy and nourished even more wide-reaching claims.

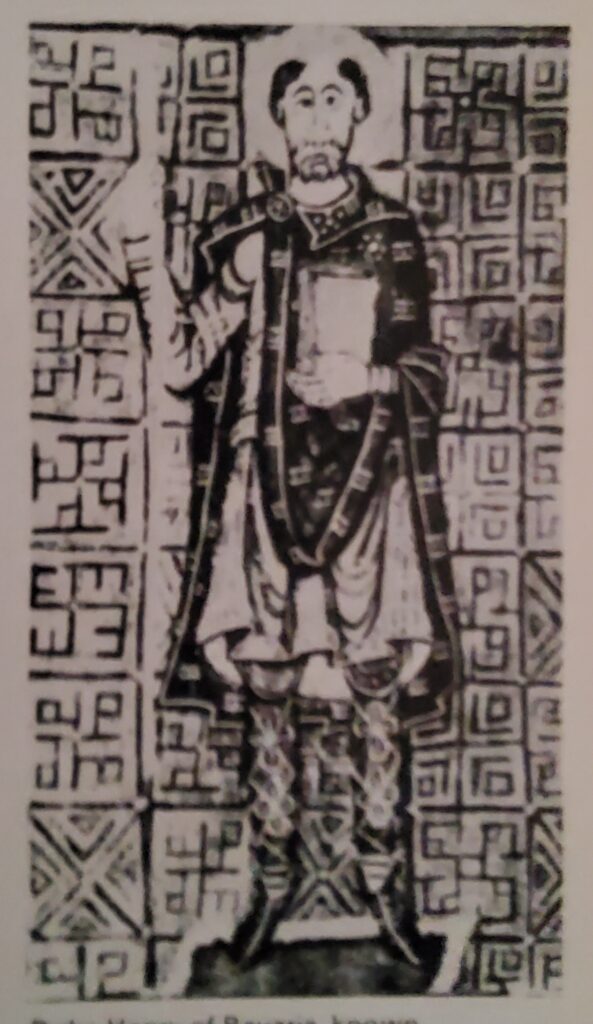

The monarchy was now in theory elective and that theory was eventually to have far-reaching consequences. By the second half of the tenth century, the power of the regional German landowners, had become so entrenched as to be a permanent danger to the central power. Otto attempted to meet this situation by balancing the power of the lay magnates with that of the great prelates of the Church. Under what has sometimes been called the “Ottonian system,” Otto relied increasingly on these ecclesiastical magnates for the chief officers of the administration of the empire. In the future, this close involvement of Church and State, was to have historic consequences.