St. Benedict’s monks tried to poison him, on one occasion it is said – and they often disregarded his instructions, but monasticism in the West, was created by St. Benedict. Before he founded Monte Cassino in 520, there were numerous other groups of monks in Europe, all with their own monastic rules, but Benedict’s Rule for his followers was the first to achieve general acceptance. It provided an ideal for monasticism that was at once disciplined and possible to achieve and maintain. With its emphasis on the individual monastery, Benedict’s Rule was ideally suited to a world degenerating into chaos ; and indeed, it was largely in Benedictine monasteries that classical learning survived during the Dark Ages. Perhaps more than any other single force, the Rule of St. Benedict gave adolescent Europe a message of fairness and a tradition of Christian behaviour.

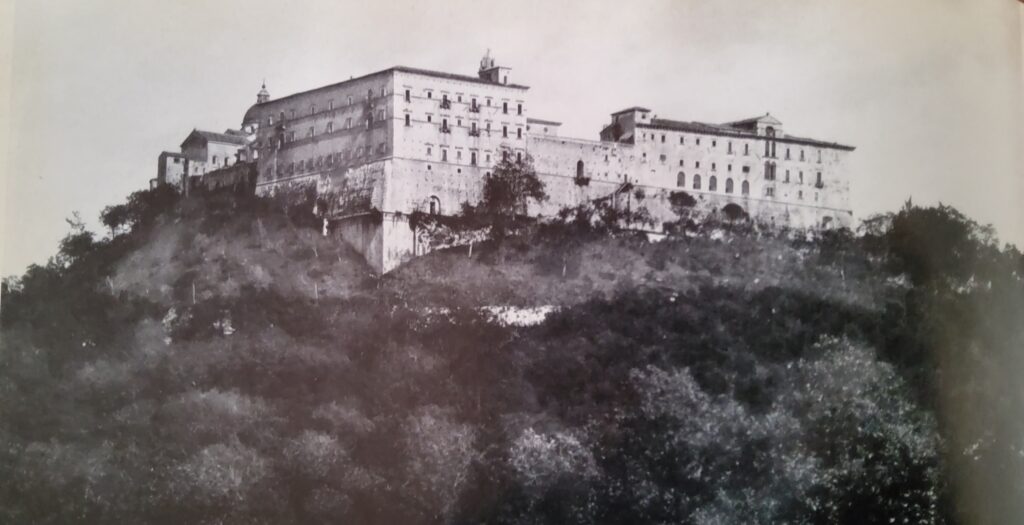

Some eighty-five miles southeast of Rome, the traveller to Naples, sees on the rocks of a towering hill, a large fortress-like building, with the cupola of a church in its midst. It is the abbey of Monte Cassino, reduced to dust by the Allied Air Forces in 1944 and now rebuilt in facsimile, to replace what was destroyed. In the early sixth century this was a remote region traversed only by herdsmen who were still pagan and on the summit of the hill, was a ruined temple of Apollo, together with a still earlier ruin of a fortress. About the year 520 the abbot Benedict, some forty years old, arrived at Monte Cassino with a small group of monks. He was attracted to the place, perhaps by the solitude of the hill and by the building stone available from the ruins.

St. Benedict was born into a family in the higher level of society, possibly Roman in origin, but then settled in the central Italian province of Umbria. The youth studied first in Rome, but left the city with his education unfinished to live first as a hermit and later, as the abbot of a group of small monasteries at Subiaco, thirty miles east of Rome. After repeated troubles with insubordinate monks, he left Subiaco and led a faithful group of followers to Cassino. The new monastery prospered and drew the attention of the Gothic king and warrior Totila, who visited Benedict at Cassino in 542. Five years later, the abbot was dead. Neither Benedict nor his contemporaries could have imagined that Monte Cassino, more than a thousand years later, would be looked upon as the cradle of medieval civilization and that he himself, would be hailed by a pope as the “‘Father of Europe.” What assured him lasting esteem was the writing, about A.D. 530 – 40, of his rule, or code of behaviour, for his spiritual sons at the abbey.

We must not imagine Benedict’s monastery as a large and regularly planned building complex, with church, dwellings, cloister and the rest. It was probably a small group of low, shed-like, contiguous structures, half-stone and half-wood, one of which would have been the chapel, another the refectory and a third, the dormitory. No doubt there was additional accommodation for novices and guests. There was no cloister and the oratory was a simple room with wooden benches or stools and a stone altar. In the upland valley below the buildings, the monks cultivated vines and olives, with fields of cereals and legumes. The life was that ofa small, simple Christian community of devout laymen.

St. Benedict and European Monastries

The monasteries of western Europe in A.D. 500, lacked firm cohesion at every level. A few, like St. Martin’s Marmoutier near Tours in France, were bishops’ foundations, but most were outside the regular church organization. The frequent siting of a monastery and still more a hermitage, in a desert or some other inaccessible spot, far from the sphere of a city bishop, made what links there were to the official church very tenuous. Nor was there any organization into groups or alliances. There was no “order” or “institute.” Every monastery, if not a cluster of small communities as at Subiaco, was an independent house under a single abbot. Finally, there was no generally accepted rule. The directories that existed, were either mere codes of liturgy, penances and punishments, or idiosyncratic rule books such as the contemporary Rule of the Master. Each monastery depended entirely on its abbot. Monks could come and go from house to house, sometimes drifting all through life in this way.

In such a situation, the genius of Benedict found its opportunity. Though not a trained writer or theologian, he was familiar with scripture; with the writings of the Desert Fathers and of Basil, Leo the Great, and Augustine; above all with the Conferences and Institutes of John Cassian, but the end product of his reading and meditation was a document, original alike – in its spiritual wisdom, its comprehensive scope and its refined brevity. It is relatively short. Indeed, if liturgical instruction and scriptural quotations are disregarded, it is very short, but it established the framework of the whole life of a monastery – disciplinary, domestic and economics – and the whole course of the monk’s activities, both external and spiritual. The Rule provides for patriarchal government, which entrusts full authority and responsibility to an elected abbot. The adherents to the Rule are to remain in one place, be obedient and practice monastic virtue. The main function of the monks and the focal point of the community, is the Divine Office or succession of services, which inspires the work, study, prayer and meditation; with which the rest of the day is occupied. Goods are held in common, but there is no specific vow of poverty — a feature of immense importance, for the performance of the works of mercy. In addition, room is found for brief but profound instructions, that combined common sense with spiritual wisdom. Of this life, the abbot and the Rule, were the two pillars and the vow of stability (remaining in one place), which Benedict instituted, gave streneth to the whole.

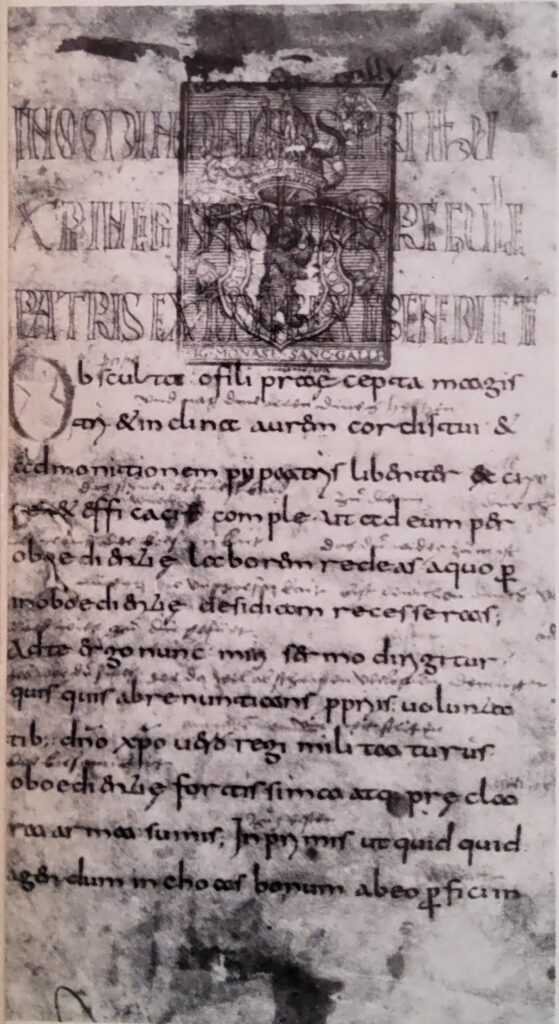

There is no autograph or early contemporary copy of the Rule, but as might be expected, the extant manuscripts are very numerous. They probably exceed in number those of any other ancient writing, save the Bible. The oldest known Manuscript is English, probably from Worcester. Written about 700 and now in the Bodleian Library at Oxford. This, however, is not the most trustworthy text. That distinction, is acknowledged by modern scholars, to belong to manuscript 914, of the ancient library of St. Gall in Switzerland. The distinguished palaeographer, Ludwig Traube, showed in 1898 that the St. Gall manuscript, was written about A.D. 817. It is a close, if not an immediate copy, of the manuscript brought, from Rome to Charlemagne in 787, to be broadcast throughout his empire. Charlemagne’s text is thought to have been a faithful copy of the original. It differs considerably from the smooth “vulgate” text, which removed the vernacular Latin forms and constructions of the original, to became standard, from early times to the present day.

Until about 787, the forms and machinery of the decayed imperial system had continued to function, however weak and disfigured they may have been. When the young Benedict was a student at Rome, Boethius, the philosopher and friend of Theodoric, was writing his theological and philosophical treatises and planning to translate the whole of Plato and Aristotle into Latin. For the Roman Church, a golden age of liturgy and musical creation and legal study was just ending. Fifty years later, all this had vanished. Rome still survived, but the old official, educated class was gone. The papacy and clergy had begun to fill the administrative void. The Rome of the popes had succeeded the Rome of the emperors. The old literary education and thought, had ceased to exist in Italy.

The life of St. Benedict spanned this unique historical divide and the Rule was actually written while armies were fighting for the control, or the destruction, of Rome. He, along with others of the same historical period, is one of the group known familiarly to historians as “the founders of the Middle Ages.” Heirs themselves to the legacy of the past, they transformed and reinterpreted its treasures into a form acceptable to the world that was coming into being. Thus, Benedict summed up in simple form, the monastic teaching of Egypt and Asia Minor, already latinized by Cassian. He incorporated the Roman tradition of firm but just government, giving the entire inheritance to an institution, that was to be of great significance for almost a thousand years of European history.

It also happencd that in so doing, he gave to that institution a viability that it had not hitherto possessed and ensured to it a particular character, both material and spiritual, that was essential to its survival. During his lifetime, the final disintegration of the Roman Empire of the West was taking place. Rome, throughout its centuries of dominance, had been the only centre of government and administration, of economic and financial life and to it, all talent had flowed. Both literally and figuratively. All roads led to Rome. In the later centuries of her Empire, all methods of government, all articles of commerce – from cooking-pots to mosaics, from villas to ampitheaters and forts – were standardized in Rome. Blueprinted and mass-produced throughout the provinces. It was this fact that had made the spread both of Christianity and monasticism physically possible.

After the transfer of the capital to Constantinople, especially after the invasions around 400, all centralizing influences weakened and broke down. Fragmentation replaced consolidation and the main unit of existence, was the self-supporting village or estate. To such a world, the monastery of the Rule was perfectly adapted. A compact economic unit, almost entirely self-contained and self-supporting, with its food cultivated by its inhabitants, with domestic animals, arts and crafts. Within its ambit, it had a small surplus for market with which to buy a few necessities, such as metalware and salt.

The monastery was also self-contained in its life. The monks lived, prayed and studied in their monastery and worked in its sheds and gardens. They had no employment or office that took them away from their enclosure, for this, as the Rule said, would be altogether harmful for their souls. They could indeed be sent on errands, to market or on the business of the house, but this was only infrequent, not to be spoken of when accomplished. They had no superior beyond the abbot and no alliance with any other community. In the background, was the protective and punitive jurisdiction of the bishop, but this was rarely felt as long as all went well.

It was a microcosm of ages and types. Recruitment was of two kinds, the one of adults — some of them possibly clerics or monks from elsewhere. The others from the illiterate native peasantry — children, offered to God by their parents, to be educated in the monastery and then normally to become monks. All ages were therefore present, all classes from the educated and well-born, to the illiterate Goth and ex-serf.

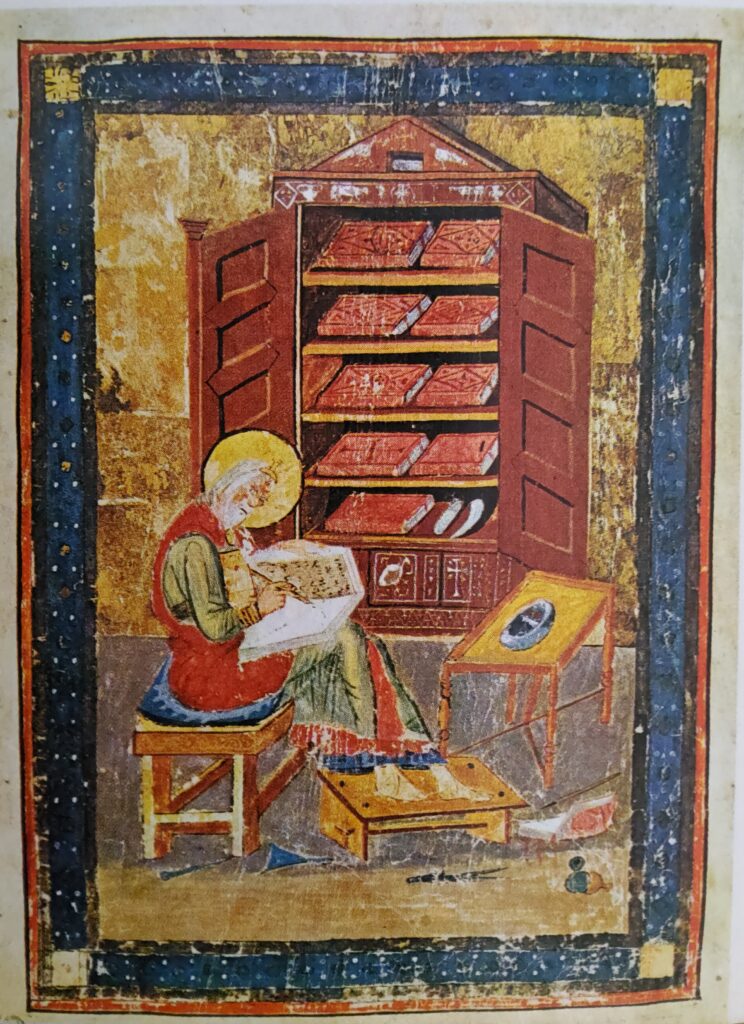

There is no hint in the Rule, as there is in the contemporary scheme of Cassiodorus, a Roman monk who founded monasteries on similar lines, of the function of monks in copying manuscripts and preserving classical literature; but the provision for reading — both private and liturgical, presupposes books and books presuppose literacy and writing, just as the presence of children made education necessary. If the Rule did not prescribe teaching and learning, it certainly did not forbid them. The careful copying and composition of books, with their lavish binding, ornamentation and illustration, both for the liturgy and for the library, inevitably developed. No doubt, many of these activities and tendencies were already present in monasteries in different degrees when Benedict wrote, but in later ages without the Rule all would have depended upon the abbot — who might countenance or command either a stricter, more penitential life with longer prayers, or a less well-knit and self-contained regime.

The Benedictine Centuries

Contrary to the venerable myth of Benedictine history that pictures the Rule spreading far and wide almost at once, it is certain that its influence was not widely felt for a century. A generation after St. Benedict’s death, Monte Cassino was sacked by the Lombards, in 581, but the story ofa group-migration to Rome and the foundation by Gregory the Great of monasteries, observing the Rule, has no sure authenticity. Pope Gregory indeed knew the Rule and wrote an account of St. Benedict, but there is no other mention of the abbot’s name till a century after his death. Such evidence as exists seems to establish that for almost two centuries the Rule was only one of several, used either separately or in conjunction in the monasteries that continued to multiply in Western Europe. It was only by a gradual process – the reverse of Gresham’s monetary law- that the practical and spiritual excellence of the Rule gradually won for it; first, a wide popularity and later, an exclusive superiority. At last Charlemagne, who was not infact, a great patron of monks, could ask if there were any other rule. His son, Louis the Pious, endeavoured in 817 to impose Benedict’s Rule, as the sole code for all monasteries of his empire.

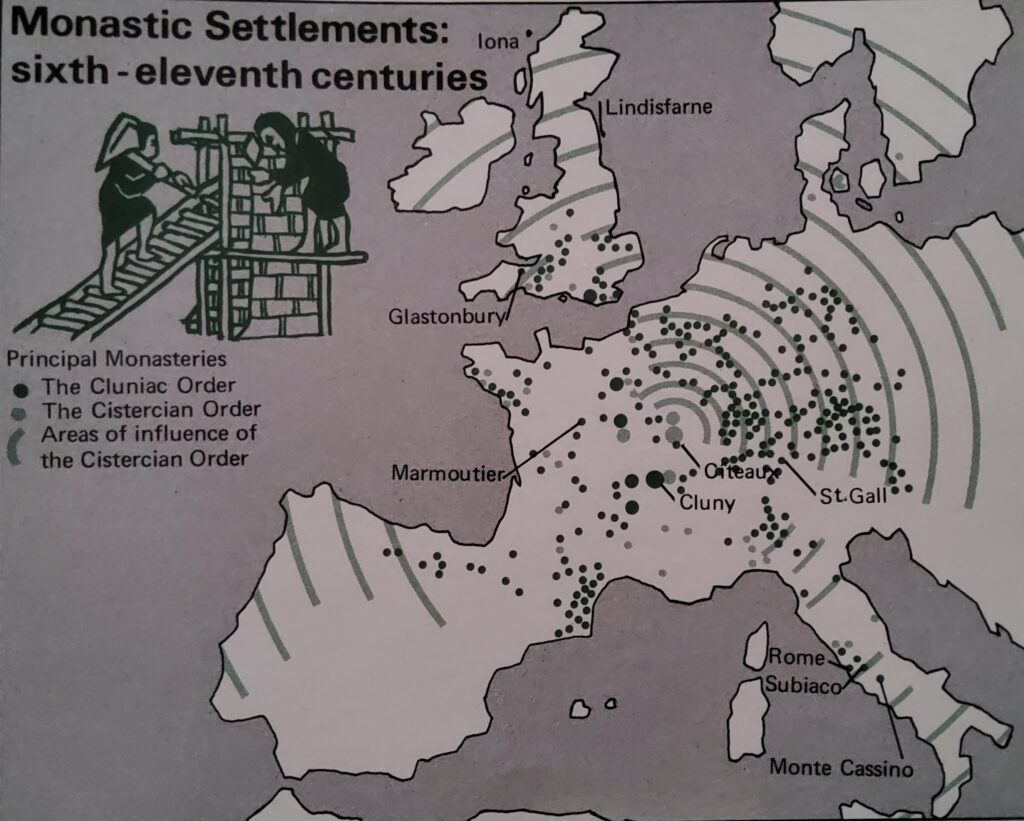

Henceforward, save in the Celtic regions, Benedict’s Rule was indeed the only rule for two hundred years (800-1000). When new orders came into being in the eleventh century, most of them — including the greatest, that of the Cistercians, followed the Benedictine Rule, while modifying it variously in practice, in the direction of austerity, hermit life, or of a wider activity. During the same period, the Rule was followed by all organized religious women. So wide was the extension of the monastic order, that the years between 600 and 1150 have been called the Benedictine centuries. It is true that in that epoch, almost all the monks followed the Rule and that the particular qualities of the Rule impressed themselves on all monks and through them, on the whole Western Church. What then were those qualities?

The first, perhaps, was its simplicity. Granted that the monastic life is a valid form of Christian dedication, the Rule appears as the simple application of the teaching of Christ to that life. Flexible discipline, absence of distractions and the elementary Christian duties of prayer, self-control, service and mutual help – make up the Rule. Such an existence, lived in the spirit of St. Benedict, has the regularity and variety for a successful integration of body and mind.

Beyond and above this are certain positive qualities – a rule of life. In contrast to so many religious ordinances, the mention of death is rare and there are no directions for the last moments and burial of the monk. Benedict is dealing with life and beyond life with the reckoning that is the sole but solemn sanction proposed again and again as a warning to his all-powerful abbot. Next, there is the stress on mutual love, aid and service. Though the monk has left “the world,” he has not left his fellow Christians and his love of God, can be fulfilled and tested by his love of his brethren, who may be frail or unattractive in body or spirit.

Though Benedict did not envisage any external work for others, his monks were, in fact, agents of great power in the development of medieval Europe. As a large majority of the trained and educated minds of Europe were to be found in the monasteries, a majority also of the leading bishops and counsclors of emperors and kings were of their number. Inevitably, also, monks were almost the sole missionaries. Most of the priests outside the abbeys were tied to their rural churches, as the appointees of the local landowner or group of urban citizens. They were also, for the most part, either married or living a family life, with a consort recognized by convention, if not by law. It was left to the monks of Ireland, Scotland, England and Germany -Columbanus, Aidan, Boniface, Willibald, Anskar, Suitbert and the rest — to carry the Gospel to central and northern Europe. Gradually the monks gave to the whole Church their devout practices and spiritual outlook. Their liturgical arrangements were adopted by the secular clergy and by Rome herself. Lay devotions reflected monastic practice, since to that age the monastic way of life seemed the only perfect form of Christian life. The monks of St. Benedict, in fact, without conscious effort, brought the attributes of monasticism to the whole Western Church. Of the great saints and writers between 1000 and 1200, the majority were monks: Gregory VII, Anselm, Bernard, Abelard, Suger, Eugenius III, Ailred and a hundred others.

All these were sons of St. Benedict, following the Rule that they had learned by heart as novices and heard each day in their chapter-house; the very name, chapter-house, was taken from the chapter of the Rule read publicly there daily. Throughout their lives they remembered well, the passages in which Benedict exchanged the language of the legislator for that of the experienced father of a family and set out counsels of justice and moderation, humanity and gravity, reminding them that the service and love of Christ must be their only aim and God’s judgment, the only criterion of their action. Although historians have not mentioned this, it may well be that the greatest achievement of the Rule of St. Benedict was to give to adolescent Europe a message of fairness, of human feeling and of civilized and Christian behaviour. Such counsels- given to the moulders of opinion and the governors of Europe in the centuries when Western civilization and thought was coming to maturity – were an influence second only to that of the Gospel, in furthering the spirit of tolerance and fair dealing, as part of the Christian life.

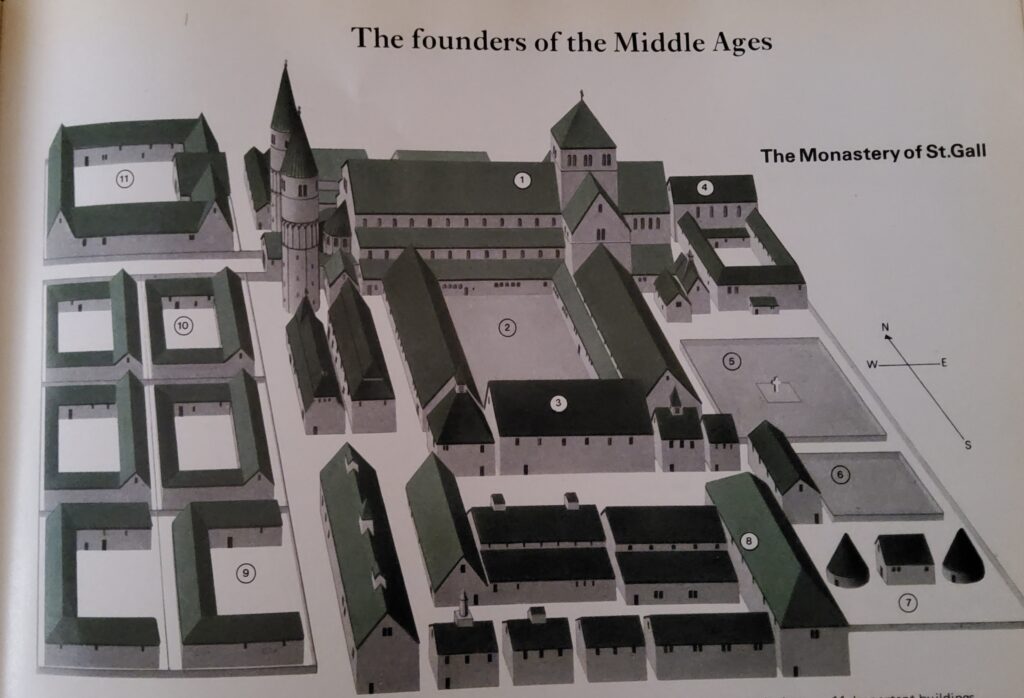

- The basilican church, with transepts, square tower, an apse at either end and two detached conical towers at the west end.

- The cloister, surrounded by monastic buildings; dormitory to the east (right) and cellar to the west (left).

- The refectory on the south side of the cloister, parallel with the church.

- To the east of the church are two cloisters belonging to the novices quarters and the infirmary.

- The monastic cemetery with a cross in the centre.

- The vegetable garden.

- Enclosures for poultry.

- The buildings far south of the church (in the foreground) include the kitchen, bakery and brew house, the press, the bar and other workshops.

- Enclosures for horses an cattle.

- Further farm quarters.

- Important buildings including the school, the scriptorium, the guest house and the abbot’s house.