The Visigoths, led by Gaiseric, settle in North Africa and challenge Rome.

Ireland before St. Patrick

According to the most ancient traditions of Ireland, her history had been linked to that of the Mediterranean world long before the coming of St. Patrick and the religion of Rome. Even after St. Patrick, the history of the country was to remain, the preserve of an oral tradition handed down by a class of minstrels or bards. In western Europe, these minstrels were the latest heirs of an heroic Iron Age society, of which the earliest example known to us was the Greece described by Homer. At the time of Patrick’s mission, Ireland was ruled by Celtic kings and her society was by then entirely Celtic. Yet the picturesque and misleadingly precise lays of the bards not only traced the descent of every one of these kings back to the most remote past (genealogies which, after the acceptance of Christianity, were to stretch back to Adam), but also told of four conquerors, who had preceded the Celts.

Their origins and their destinies must necessarily be classed as obscure, but we are told that when the original settlers of the island were defeated by the seafaring Fomors, many of them fled to Greece. The next race of invaders, the Tuatha De Danann (in whose name there might be a fossilized form of “Danai” — one of the names by which the ancient Greeks were known), made use of magical powers to assist them in their conquest. However, these arcane skills were not proof against the Milesians — according to the legend the last conquerors of the island and also a Celtic people.

The Milesians, whose name also has an attractively Mediterranean flavour, originally came from Spain. This tradition is neither inherently absurd nor lacking in some archaeological evidence. It is now fairly generally accepted, that Phoenician traders from the Mediterranean reached Cornwall in their quest for tin, sufficient indication of the skills of the early seafaring peoples. More direct links between Ireland and Spain itself may be seen, in the remains of megalithic monuments in these two countries, as in other parts of coastal Europe.

Whatever their origins, the Celts were well established in Ireland at the time of the Roman conquest of Britain. Their numbers were swelled by the arrival of small groups of refugees, fleeing before the invading army. We know from the account of his son-in-law, the historian Tacitus, that the Roman general Agricola had contemplated the conquest of the island — not, it appears, because of military necessity, nor in the hope of material gain; but rather as a tactical move of psychological warfare against the Britons themselves, to impress on them the omnipotence and ubiquity of Roman arms. Alas, the demonstration was never made. The conquest of Ireland by Rome, if so it may be termed, did not come until four centuries later, when she received her religion and first literate culture at the hands of a Roman missionary. During the intervening period, there is evidence of trading with the Empire and also of some raiding by Irish adventurers. Yet, for the most part, these centuries were spent in the internecine warfare between seven kings who divided the country among them. During this period, the most powerful house, attempted to make good their claim to be High Kings.

In many ways, Ireland was remarkable among the countries of western Europe in the early Middle Ages, especially for the survival of an ancient Iron Age culture, complete with the institution of kingship. More importantly, still is the early sense of a unity of culture that surmounted the political divisions of the country and was expressed in the use of a common language and a common legendary tradition. It was this tradition, that was so important a feature, in the success of missionaries of the fifth century.

lreland after Patrick

The brilliant story of Christian culture in Ireland and its importance to the civilization of medieval Europe has been touched upon. The talents of the Irish in the humane arts were not, however, matched by an equal skill in the business of politics. When the Norse invaders fell upon the country at the end of the ninth century, the Irish were unable to dislodge the intruders. Nor could they sink their differences in order to form an effective counter-balancing power. The reason, may perhaps be found, in the continuing clannish structure of Irish society. Despite the temporary unifying effect of the reign of Niall, the country continued to be divided into warring territories.

The Norsemen brought not only destruction to the thriving cultural life of the island, but also a new principle of social organization in the towns that they founded, such as Limerick, Wexford and Waterford — and the trade that they conducted. Furthermore, the Norsemen, engrossed in their trading activities and with their overseas territories in Man and the north of England, never seem to have concerned themselves with the outright conquest of Ireland. Thus, unlike their neighbours in England, who in the eleventh century, surrendered independence for a strongly unified state, the Irish were free to continue their interclan rivalry, until during the twelfth century, they too felt the weight of Norman conquest and entered a tragic period of foreign oppression.

Only once, did the situation seem likely to alter. In the early years of the eleventh century, Brian Boru, King of Munster, usurped the high kingship and united the country. On the historic field of Clontarff, in the year 1014, he defeated a great army composed of the Vikings of Dublin, of Man and the Isles and their Irish allies. The power of the Vikings in Ireland was broken, but in the same year Brian Boru, who had described himself proudly as Imperator Scottorum and who seems to have tried to modify the fragmented nature of Irish society, was killed. The Norsemen’s influence was now limited to the important, but no longer menacing, trading communities. The petty kings and great families of Ireland resumed their age-long struggles, which even the first impact of the Norman conquest in the 1160s did not check. Even the Normans, who never conquered this turbulent country, soon found themselves involved in the complexities of Irish clan politics. In the end, it was this very clannishness, that enabled the Irish to retain their strong identity as a nation throughout the centuries that followed.

The early history of Scotland

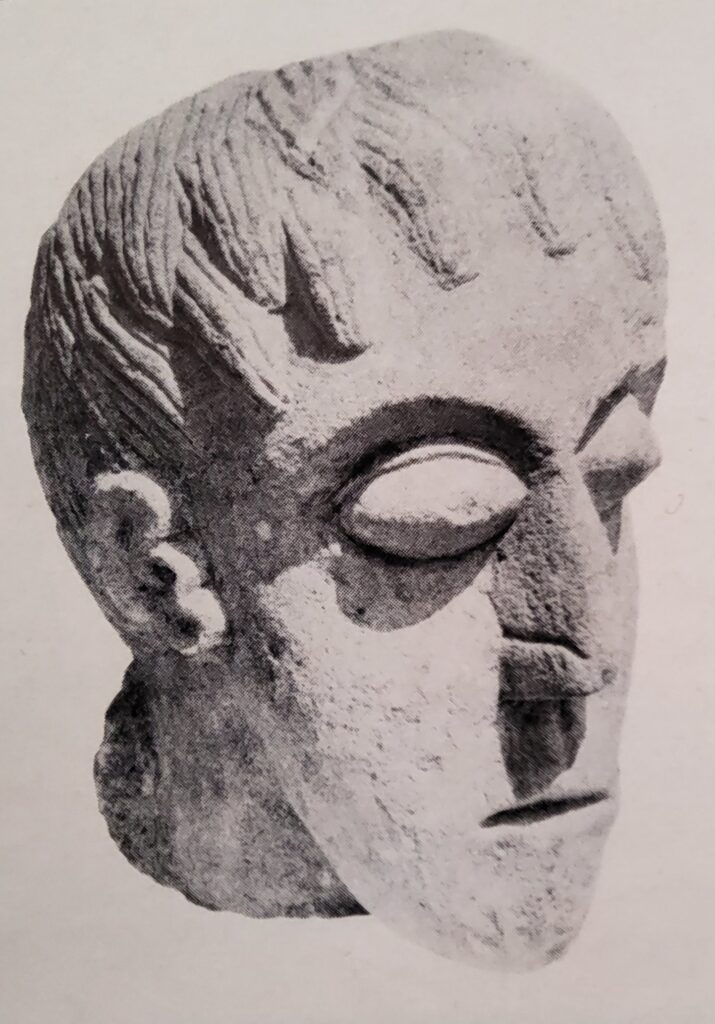

We have seen how St. Columba established an outpost of Irish Christianity on Iona in the sixth century. The island was part of the Scot kingdom in northern Britain that had been founded by settlers from Ireland itself. The original inhabitants of Scotland — the Picts — are one of the more shadowy peoples of European history. It seems likely that they settled in the country before the arrival of the Celts in Britain and had received Christianity during the fifth century at the hands of St. Ninnian.

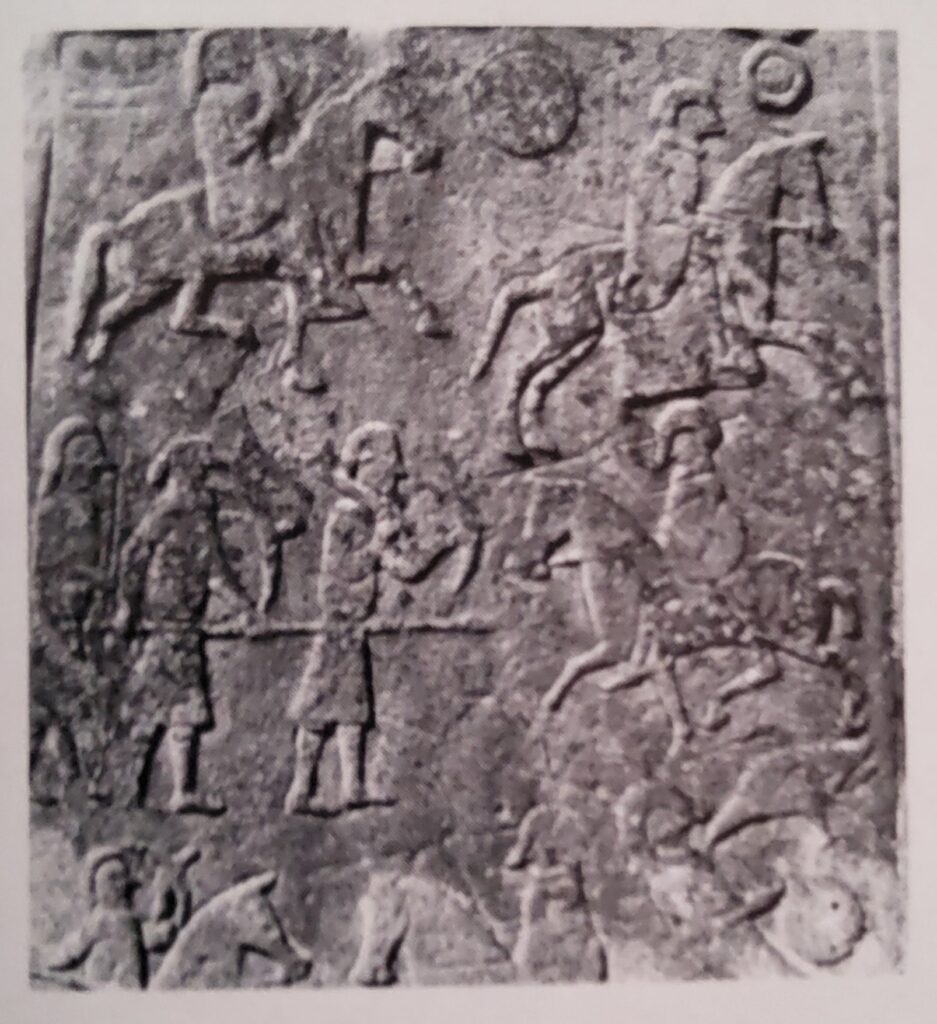

At the time the community of Iona was founded, the land we now know as Scotland was divided among several kingdoms: the Picts to the northeast; the Scots; the British in Strathclyde to the southwest; and the Angles in Northumbria to the southeast. During the ninth century, a new power established itself in the Hebrides and the mainland districts of Caithness and Sutherland. This was the Norse earldom of Orkney, which all but destroyed the Pictish kingdom. As a result, before the middle of the century the Scottish king, Kenneth I (the first) MacAlpin, was able to extend his control over what remained of the kingdom. It was with his house and its successors that the future of Scotland was to lie. In the tenth century they succeeded in winning the lowland areas of Lothian and the Tweed frontier from the English King Edgar. In the early eleventh century, Kenneth MacAlpin’s successors acquired the whole inheritance of the last of the kings of Strathclyde. The power of the Earldom of Orkney had gradually been Eroded, so that by the end of the eleventh century, only the isles and the northeastern most tip of mainland Scotland, was controlled by the Norwegian rulers.

The Vandals in Africa

In 451, Europe was controled by the menacing power of the central Asian steppes, that had so long affected her destiny indirectly. Fear of the Huns had been the force that had driven the first wave of German invaders into the Roman Empire during the fourth century. Gradually, their long trek westwards was to lead the two great confedcracics of the Goths, to set up kingdoms in the old lands of the Roman Empire.

The first Germanic kingdom to be established within the Empire was, however, that of the Vandals. They had been settled on the Danubian frontier as early as the third century and had, in the figure of the noble Stilicho, given Rome one of her greatest statesmen. However, Stilicho, like the Roman Aetius after him, was to fall victim to the murky intrigues of the court of the later Western Empire. Among other charges against him was one of having invited the barbarians into the Empire in the fateful year 406.

Crossing the Pyrenees

It is true that the Vandals were among the group of tribes that crossed the Rhine in that year. Unable to find territory in Gaul, they continued to move west, crossing the Pyrenees three years later. In Spain the Vandals lived on uneasy terms with the Empire, to which they made nominal allegiance and with their barbarian neighbours, the Visigoths. However, they were even at this stage showing abilities in seamanship that were later to make them the first barbarian naval power in the Mediterrancan. In 429, under pressure from the Visigoths, they were led by their king, Gaiseric, to Africa. Here again we find contemporaries charging the imperial commander of the province, Boniface, with collusion, but the charge can almost certainly be discounted and the defeat of Boniface himself was so complete and so rapid that history, as distinct from scandal and rumour, has been denied the opportunity of fabricating any real explanation of this supposed treachery. Within five years, the imperial government had been obliged to recognize the de facto power, that the ruthless leader of the Vandals had won for himself in Africa. During his long reign of fifty years, Gaiseric (d. 477) not only established a kingdom in Africa, but became a menace to Mediterranean shipping and seriously threatened the Eastern Empire. In 455, he sacked Rome with legendary brutality. He defeated all attempts to overthrow him and concluded a peace with the Empcror in which Zeno recognized the barbarian power in North Africa and Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica and in the Balearic islands.

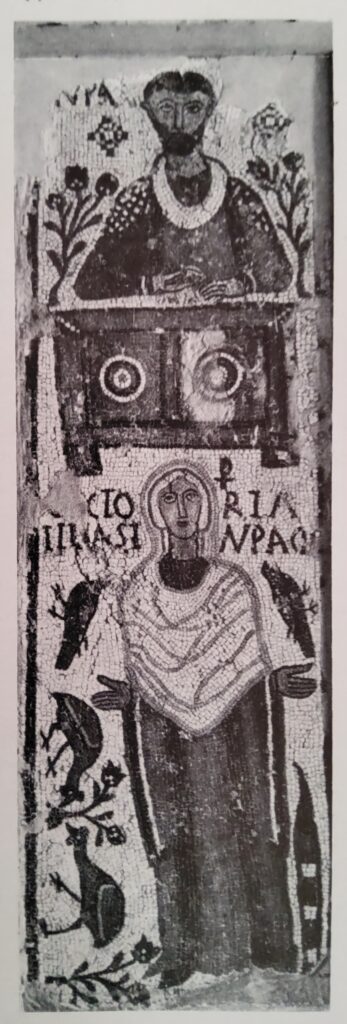

The Vandals remained a ruling minority in Africa, settling on the states of dispossessed Romans. They retained their ancient customs and traditional method of mounted warfare, but gradually succumbed to the unaccustomed life of southern luxury. The Roman citizens of the former province retained their own law courts and continued to serve in the main offices of the civil administration, but in one crucial respect, the life of the conquered population was frequently one of bitter oppression. Like Germanic peoples elsewhere, the Vandals were Arian Christians. Persecution of the Catholics, by fines, confiscation and outright cruelty, recurred throughout the Vandal period.

The Moorish Onslaught

After Gaiseric’s death, Vandal power in Africa was under increasingly severe attack from the Moorish tribes of the interior. Although toward the end of the period some rapprochement was achieved with the Eastern Empire and the persecution of Orthodox Christians ceased, the last Vandal king, Gelimer, renounced the alliance. The kingdom fell prey to the armies of the Emperor Justinian under the command of Belisarius. The incursions of Attila were among the more sensational events in the history of Europe during the fifth century, but his Hunnic ancestors, had long before set in motion a train of events that had far-reaching consequences for the Empire in the West. The century of Vandal rule in Africa was paralleled by the Ostrogothic domination of Italy and outshone by the enduring state the Visigoths established in Spain after the Vandals left.